The Science of Folklore ALEXANDER HAGGERTY KRAPPE The

advertisement

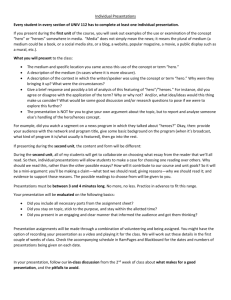

The Science of Folklore ALEXANDER HAGGERTY KRAPPE The Norton Library W W NORTON & COMPANY INC NEW YORK CONTENTS I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS INTRODUCTION vii xv THE FAIRY TALE THE MERRY TALE THE ANIMAL TALE THE LOCAL LEGEND THE MIGRATORY LEGEND THE PROSE SAGA THE PROVERB THE FOLK-SONG THE POPULAR BALLAD CHARMS, RHYMES, RIDDLES SUPERSTITION PLANT LORE ANIMAL LORE MINERAL LORE, STAR LORE, COSMOGONIC LEGENDS CUSTOM AND RITUAL MAGIC FOLK-DANCE AND FOLK-DRAMA FOLK-LORE, MYTH, AND RELIGION 1 45 60 70 101 138 143 153 173 189 203 230 245 BIBLIOGRAPHICAL GUIDE INDEX 336 337 262 269 287 301 310 [15] THE FAIRY TALE What are the general characteristics of the type, what are the features which may injustice be ascribed to all fairy. tales and which thus distinguish them from other types of popular fiction? First of all, the fairy tale is essentially melodramatic in tone and character. If protagonists are types and few in number: the hero (or heroine), the kindly helper or helpers, and the villain or villains. As a rule there is only one hero. The exceptions are few and far between, one being the above-mentioned "Tale of the Twin Brothers," another that of the "Four Skilful Brothers." Yet even when there are several heroes their distinguishing marks are practically nil. Thus in the "Tale of Twin-Brothers" it is expressly stated that in their physical appearance the two brothers are so much alike as to be indistinguishable, and in the other example adduced the protagonists are, quite alike. except that each possesses one marvellous quality which the others lack. The typical fairy tale hero is essentially the hero of a melodramatic in that he possesses whatever virtues one may wish for whilst no mention is made of possible flaws. Nor is there any evolution of character discernible in, most fairy tales. The hero [16] is supremely good or clever at the outset and obviously remains so till the end. Again there are but few exceptions to this rule, and these owe their origin no doubt to the tendency of didacticism discussed above. Thus, for example, in the tale of the Golden Bird the hero repeatedly disregards the advice of his kind helper and gets into trouble in consequence. Only on the last quest does he mend his ways and attain his goal. In the Marchen at the base of the ancient story of Cupid and Psyche the heroine twice violates the taboo and opens a forbidden box; at last she manages to resist her fatal curiosity. The makers of fairy tales, however simple their art, were yet quite aware of the advantage of foils to make the hero's or heroine's excellence of character or beauty stand out more clearly. Thus in a number of types the hero will have two numskull brothers and the heroine will be provided with one or two envious sisters, anything but models of beauty. Often, too, these brothers or sisters will attempt the task and fail miserably, whilst the hero or heroine carries it to a successful conclusion. The melodramatic character of the fairy tale comes out very clearly in the description that is usually given of the general conditions of the hero or heroine at the outset of his or her career. They are said to find themselves in a truly miserable state. The hero is usually the youngest son, scorned and neglected by every body around him, whilst the heroine is often ill-treated by a wicked stepmother or stepsisters. In a large number of types the hero is an orphan outright or else a widow's son, the loss of the father evidently being considered as more serious than the loss of the, mother. In certain types he is even depicted as a dunce whose intellect is slow in awakening. The typical hero of fairy tales may therefore be truly considered as a 'self-made man', a type which has been to this day the favourite hero of melodrama. Nor is there anything primitive about the virtues possessed by the hero and therefore evidently meant to be inculcated. The chief of these is of course courage. Next come cleverness (sometimes of the Ulyssean kind), presence of mind, but also generosity, willingness to listen to good advice, kindliness and common decency. In the heroine courage naturally falls somewhat into the background, but the other virtues remain much the same. All these are qualities which have always been prized and presumably will continue to be for centuries to come. That there are occasional traits of savagery need not be denied, and a few words on the subject will prove helpful. [17] With all his virtues, however, the hero would hardly succeed in his task if it were not for kind helpers, sometimes simply helpful animals, more often helpers of' a supernatural kind. It is true, he does not obtain their assistance without any personal merit. As a rule, he wins their friendship by some kind or charitable deed, sometimes merely by a courteous answer, whilst his brothers, rude and, unkind, not only obtain no help but often see themselves frustrated by those very powers they have offended. In isolated cases, for example in “Puss in Boots”, the hero wins the friendship of, his animal helper without any meritorious deed of his own. In a well-known type he acquires the good will of three animals by dividing between them a piece of booty to which they lay claim. The helpful animal is often one of the flock which the hero or the heroine have to pasture, a ram, a bull, or even a horse. Such is the case in the type which underlies the story of Phrixos and Helle In the widespread tale of the magic ring, at the basis of the Oriental story of Aladdin, the helpful animals are a snake, credited with having furnished the ring (for reasons which we shall discuss further on), a dog and a cat. The beast may be a wild animal, a fox or a wolf, sometimes even a lion. The animal is endowed with speech, not necessarily because at the time when those types arose man believed animals on much the same level with himself, actuated by human desires and human passions, but more probably because without such a fiction no story is possible in which animals play any conspicuous role. In a number of types and of variants of types the animal helper in the end turns out to be a metamorphosed human being, and it may occur to some that such was the case in all stories in which an animal helper occurs. This conclusion would be hardly warranted, however. For not only is the number of versions improved by a metamorphosis motive relatively small, but it would be rather difficult, moreover, to see why this motive, quite interesting in itself, should have been dropped. On the other hand, it is clear that as a rationalizing feature, to make plausible the animal's anthropomorphism, it should have been added by sophisticated narrators. .............. [21] Like every good melodrama, the fairy tale has its villain or villains. These villains may by their position to the hero be classed under two headings. They may be nearthough to be sure hardly dear to him,, or they may be entirely unconnected with him until his tasks bring him in contact with them. To the former belongs the array of hateful uncles, ugly stepmothers, envious brothers or sisters or stepbrothers and stepsisters, treacherous companions and, in one isolated type at least, an unnatural mother. Among the latter must be counted the medley crowd of giants, dragons, ogres, revenants, witches, sorcerers, and magicians found in most types. The former class needs on the whole little comment. The realism underlying the stepmother, stepbrother and stepsister conceptions is of course evident. The occurrence of envious brothers and sisters is to be explained on the basis of the foil idea, the object being to make the character of the hero or heroine stand out still clearer. The figures of the hero's unnatural sister or mother, occurring in just one type, are most probably due to a transfer, their role being originally taken by a wife whom the hero had captured against her will (the famous Samson motive). But the whole type has not yet been subjected to a thorough study. Nor does the figure of the cruel uncle require any special [22] explanation, especially to English readers who will remember King John and King Richard III. Suffice it to say that the figures of this class are genuine villains, as black as fancy can make them, who in the end meet with their deserved punishment. Very much the same holds true for the characters of the second class, except that they are under no natural obligation to the hero but meet him in fair fight, inevitably getting the worst of it. They are throughout endowed with superhuman strength, though their intellectual equipment, fortunately for the hero, is usually not, on a, par with their physical qualities. The fight between them and the hero is generally a fair one, as has been said before, for their supernatural strength is matched by the hero's nimbleness and wit. In fact, the number of types in which the hero conquers them in a regular duel is probably far exceeded by those in which he prefers to outwit them. Nor is it necessary to cite examples; numbers of tales will occur to the reader at, once. In his task the hero is invariably successful,. The opposing demons are defeated, his enemies at home receive their punishment, he marries a princess and lives happy ever after. This happy ending, without which a fairy tale is unthinkable, likewise approximates this type of fiction to the modern melodrama A fairy tale with a tragic ending is unknown, and wherever an historical variant presents such an one, as does, for example, the story of Jason, the folktale has undergone a literary re-working. [23] In the centre proper of the fairy tale stand the task or tasks, often three in number, of the hero. Their nature varies of course in the different types. One of the most common is the quest motive. Its frequent occurrence alone should have prevented folklorists from seeing in fairy tales much else besides fictions put together to please and to entertain. For there are few themes as engrossing and interesting as a good quest theme well worked out. It is the quest theme which makes stories like those of the Argonauts, or the Odyssey so vastly more charming than, say, the Iliad or the Nibelungenlied with their tedious monotony of duels and battles. What the hero goes in quest of again may vary greatly from type to type; only, since we are dealing with popular fiction, it can be nothing abstract such as Happiness or Love. On the contrary, it always something very concrete, a woman, the ideal woman, of course, a wonderful horse, a wonderful bird, the water of life, the three golden hairs of the devil, the sword of light, or maybe, an answer to some puzzling question. Again, one fails to see anything particularly primitive about all this. These things are rather such as man has always striven after, treasure, long life, and the ideal woman. That the treasure should consist of a fine horse or a fine sword merely puts am tales back into the feudal age, which is not exactly prehistoric. After all, almost every genuine hero of that age, from the Frankish Sigfied to the Norse Olaf Tryggvasson, was said to have possessed the most beautiful woman, the swiftest horse, the best sword, and sometimes, in addition, the finest hound and the most excellent ship. Next in favour among the popular tasks is probably the watch. Again, there is nothing very archaic or hoary about this motive. To be sure, ritual watches have existed for a long time past. There has been the 'wake' near a corpse, which is by no means always a social affair as in Ireland. The opening chapters of Apuleius' famous story rather incline one to a different view of the matter. There has been, further, the watch as one of the ceremonies of chivalry which all readers of Don Quixote will remember, a custom which, by the way, is still kept up in certain [24] regiments of Continental European armies. As we should but expect, after what has been said about the common occurrence of realistic elements in fairy tales, this ritual watch does turn up in certain variants of certain types, usually in the form of a wake undertakers in three successive nights by one of the three sons. of the deceased. The two eldest sons are frightened to death, but the youngest son stands the test. Yet this type of watch which can be directly derived from every-day life, stands after all fairly isolated in the literature of fairy tales. Vastly more common is the watch of the homestead under circumstances which make such a watch anything but a desirable experience. 'There is first of all the watch of the castle haunted by ghosts which have killed every human being that had attempted the task. The hero, by his conduct, a mixture of intrepidity and caution, lays the spectres, disenchants the castle and obtains a princess in reward. Them is further the story called “The Hand and the Child”. For some time past every new-born child in a house has been spirited away by a giant hand coming down through the chimney. The hero cuts off the hand or arm and eventually recovers the abducted children. There is the watch in the chapel ear the coffin of the bewitched princess who nightly rises and slays the soldiers sent to guard her, until the hero, cautioned beforehand, follows the right course to remain unhurt and to disenchant the princess. Now stories such as these are clearly told because of the thrill of the adventure involved, and all they presuppose on the part of the hearer's credulity is a belief in ghosts and 'spooks', to find which it is not necessary to go back. into the Stone Age. Another very common set of tasks is connected with wooing adventures. The hero to win the bride, has to undergo certain tests, a foot- or chariot-race, a duel with his father-in-law or, if the bride be an Amazon, with the bride herself, or he must come out victorious of a tournament, be able to solve certain riddles, or vanquish 'his father-in-law' at the game of chess. Nor is it necessary to descend to primitive culture to explain these motives. .............. [271 A good deal of nonsense, has been written on the ethical standards revealed in fairy tales. For the nineteenth-century moralists were not slow in discovering. that the ordinary fairy tale does not, any more than do the fables of La Fontaine, inculcate the lessons of the Sermon on the Mount. Yet that fact certainly does not warrant a conclusion that fairy tales are survivals representing a set of moral ideas long since overcome. As is well known, modern society is not governed by the lofty principles of the New Testament or even by Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics. Moral sentiment still is, and always has been, purely emotional, and modern public opinion clamours for the punishment of the villain. The fairy tale presents precisely this state of affairs: its villains are punished.. That this punishment should as a rule be somewhat more atrocious than is allowed by modern legislation is not a matter of surprise. The reform of criminal procedure is after all a very recent event. Nor is it to be wondered at that in his dealings with the demons the hero should display the qualities of a Ulysses rather than those of a Don Quixote. That merely shows that the narrators are people of common sense. The fairy tale is furthermore quite free theological speculations of any kind. The Christian divinity is all rigorously excluded as are the figures of the Greek and Roman pantheon. If in the fairy tales of the Arabian Nights the name of Allah occurs occasionally, that feature must be evaluated on the principle that accounts for the introduction of Hera and Athena in the story of the Argonauts, i.e. literary preoccupation. ........ .. ... [287] MAGIC The basis of all science, the historical sciences no less than the natural ones, is logic, i.e. that faculty of the human mind which co-ordinates the phenomena of the outside world according to the rules of cause and effect. Hence it is that science ends where logic ends, and whatever is not amenable to the rules of logic falls outside the domain of science. Magic, too is based upon logic, and in this respect at least it may well be regarded as something akin to science. Yet the logic upon which it rests is a faulty logic in that it finds causal relationships which upon more accurate observation are found to be non-existent. Magic is then a precursor of science in the sense that the logic on which it is built is a precursor of the logic which is at the base of all scientific work. Yet this does not mean that science is always and necessarily the successor of magic, On the contrary, both may exist side by side, not only in the same society (which would not be particularly miraculous) but even in the same mind, according as to whether it adopts a logic of rigorous fact or a logic of assumed possibilities, possibilities, that is, which cannot be proved but which can no more be disproved. All magic may be divided into two categories according to the logic on which it rests. The first has been called sympathetic magic. Its logic assumes the continuance of a relationship that has in fact ceased. If, for example, the East African shepherds as well as the ancient Israelites refused to boil milk from fear that it might hurt the cow, no one can accuse them of a want of logic. Theirs is merely a faulty logic, i.e. they assume that because the milk was once part and parcel of the cow it still is so and that therefore any hurt done to the milk (such as heating it) would likewise hurt the cow. Or, if a savage is careful to bury the clippings of his hair or the parings of his nails lest a witch get hold of them and through them work magic on him, he assumes that because hair and nails formed once a part [288] of his body they still do so, and any action exercised upon them would react upon his body. The second category has been called homoepathic magic; its logic may be rendered by the Latin proverb similia similibus. If, for example, rain is desired, water is poured out, on the theory that such an action will produce a similar one. All magic actions may be reduced to one or other of these two principles.