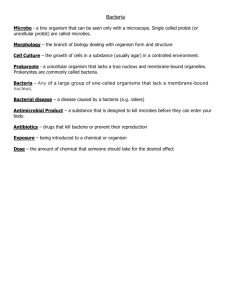

NIH Weighing Plans to Release Altered Bacteria

advertisement

The Washington Post NIH Weighing Plans to Release Altered Bacteria September 20, 1983 Author: Philip J. Hilts, Washington Post Staff Writer A National Institutes of Health panel met in secret yesterday on controversial proposals to release gene-engineered microbes into the environment, but refused to divulge whether the experiments were approved or any other information about them. The panel's executive secretary, William Gartland, said the government acted to prevent compromising trade secrets of the companies that developed the microbes. The action was the first time the NIH group closed its doors to the public on this politically sensitive subject, and U.S. District Court Senior Judge John J. Sirica rejected an early morning attempt by gene-engineering opponents to force open the session, saying the panel was acting within its rights. Two firms yesterday sought NIH approval to release gene-engineered organisms into the environment. Cetus Corp. of Madison, Wis., asked to conduct experiments to show that plants could be made resistant to an unnamed disease by gene engineering. Biotechnica International of Cambridge, Mass., submitted a proposal to put geneengineered bacteria on alfalfa plants so the plants could help fertilize themselves naturally by capturing nitrogen from the soil. The companies made no more details available, saying that the competition to put such products in the field is fierce and secrecy is necessary. Opponents of the experiments say that there have been no tests done to determine whether these experiments are risky, and the NIH panel has no ecologists or plant pathologists among its voting members to expertly assess the risk of the experiments. Gene engineering opponent Jeremy Rifkin last week sued the NIH to force the government to assess environmental risks of such experiments and possibly write an environmental impact statement for each one under the National Environmental Protection Act. Rifkin and his supporters liken the new gene-engineered plants and microbes to the introduction into this country of foreign pests, such as the gypsy moth, chestnut blight, and Dutch elm disease. Each of these was unknown in America, but shortly after being introduced began to cause great damage, which continues relatively uncontrolled. The researchers who want to carry out the experiments say they are unlikely to cause problems, since the experiments are conducted on bacteria and plants that are quite common, and they are not adding any genes to them which could turn a corn or tomato plant into a hazardous plant, or make a common plant bacterium hazardous. In addition, precautions are being taken so that the engineered organisms would not spread from their test fields. The NIH already has approved three proposals to release gene-engineered plants and microbes into the environment, but those proposals were considered in open, public meetings and discussed in detail. Gartland said he did not know why the outcome of yesterday's meeting was withheld, since stating whether the experiments were approved or not has no bearing on trade secrets. "I can't really answer why, other than that's the legal advice we got." He said the committee's withholding of such information had never been challenged before. Rifkin's suit claims that the agency approved previous experiments without adequately assessing their risk, and he is seeking to halt the experiments before they reach the field. The NIH committee, called the Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee, has no legal power or jurisdiction over companies and their experiments, but companies have traditionally come to the committee voluntarily to receive its stamp of approval as a protective measure against criticism or lawsuits. There are currently no federal regulations that govern such experiments by companies, according to one federal regulatory official familiar with the issue. Virtually all regulation of materials, whether they are gene-engineered or not, comes after a company decides to manufacture a new substance, not at the research stage. The committee has 19 members. All but one are scientists or medical doctors. The experiment releasing gene-engineered bugs into the environment, which may be the first one to be attempted outside the laboratory, involves spraying frost-preventing bacteria on plants. The bacteria are common, and normally trigger the development of frost when the temperature falls to about 30 degrees. The experiment has excised the gene that makes the bacterium trigger the frost, so that plants could survive temperatures about 7 degrees colder without suffering frost damage. The worst scenario drawn by critics is that the bacteria might rise into the upper atmosphere and disrupt the natural formation of ice crystals, possibly affecting world climate. Most researchers find this scenario, as one scientist put it, "totally ridiculous." They say they believe the bacteria are too heavy to be swept up miles into the sky, and are unlikely to have any effect on the air even if they did rise. Further, they say, the bacterium already exists in virtually all plants, and the experiments have only taken away the power of the bacterium to cause one kind of damage, not given it new powers. Copyright (c) 1983 The Washington Post