Dyslexia policy statement

advertisement

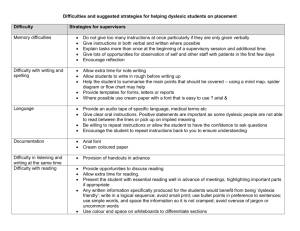

CHILDREN’S WELLBEING DIRECTORATE ADDITIONAL NEEDS HEREFORDSHIRE PSYCHOLOGY SERVICE Dyslexia Policy Statement Dyslexia Definitions Herefordshire Psychology Service supports and has adopted the following definition of dyslexia (Rose, 2009): Rose Report Definition: Dyslexia is a learning difficulty that primarily affects the skills involved in accurate and fluent word reading and spelling. Characteristic features of dyslexia are difficulties in phonological awareness, verbal memory and verbal processing speed. Dyslexia occurs across the range of intellectual abilities. It is best thought of as a continuum, not a distinct category, and there are no clear cut-off points. Co-occurring difficulties may be seen in aspects of language, motor co-ordination, mental calculation, concentration and personal organisation, but these are not, by themselves, markers of dyslexia. A good indication of the severity and persistence of dyslexic difficulties can be gained by examining how the individual responds or has responded to well founded intervention (From Rose, J. (2009) ‘Identifying and Teaching Children and Young People with Dyslexia and Literacy difficulties: an independent report from Sir Jim Rose to the Secretary of State for Children, Schools and Families.’ DCSF). (See also the British Psychological Society (BPS) definition from 1999 and reprinted in 2005, which we accept and see as consistent with the above definition). The Principles Behind our Approach to Dyslexia Firstly, we acknowledge that dyslexia is an emotive and often contested issue lacking in a consensus about its causes, its effects and its identification. However, as educational psychologists we feel we have a responsibility to explain our viewpoint and clarify where we believe misunderstandings have arisen in the use of this term in the past. Additional Needs Service, Children’s Wellbeing, Herefordshire Council, Plough Lane Hereford HR4 0LE We believe that dyslexia occurs at all levels of ability, and therefore we do not advocate a ‘discrepancy’ approach to assessment (where general abilities have to be significantly higher than literacy attainments). Assessment of progress over time in response to a specific teaching intervention is the best way of assessing the severity and persistence of a child’s reading and spelling difficulties, and whether or not these can be described as dyslexic difficulties. Although a reading test may offer a ‘snap shot’ in time of a child’s under-achievement, it cannot provide information about the other cognitive, historical, or environmental factors that may have caused or contributed to the delay. These factors can include learning, emotional or behavioural difficulties, an interrupted history of schooling, and physical factors such as hearing and vision. The SEN Code of Practice (2001) states that assessment should not be regarded as a single event but as a continuing process. Assessment information about a child’s progress over time should be gathered by schools over a sustained period of time and include: - Assessments of vocabulary, phonics and phonological skills; Information concerning the child’s progress with word reading and spelling over time; Standardised assessment information relating to word reading and spelling; Information detailing whether the child has had appropriate learning opportunities; Whether the child has made progress only as a result of much additional effort and instruction and the difficulties have nevertheless persisted. A comprehensive assessment of a child with severe difficulties would involve professionals from outside the school such as a specialist teacher or educational psychologist, and would come at the end of this process, after a period of monitoring and skills assessment and intervention within school. Dyslexic difficulties occur when other factors have been excluded, and literacy difficulties persist, in spite of appropriate learning opportunities. Dyslexia is basically a failure to learn to read or spell when other explanations have been ruled out. The term is descriptive and not explanatory. Dyslexia research is a large and conflicting area of academic study, lacking in agreement about a single cause and where simple genetic and biological factors, whilst important, have yet to be identified. However, it is now widely accepted and understood that dyslexia has as its primary cognitive cause impairments in phonological processing (Vellutino et al., 2004). Dyslexia is not commonly associated with visual factors. In the absence of a definitive medical assessment procedure, we acknowledge the usefulness of understanding dyslexia as a continuum where there are no clear ‘cut-off’ points and where children can be said to experience ‘dyslexic difficulties’ of varying degrees rather than having, or not having dyslexia. Although Dyslexia has characteristic features related to phonological processing, and a wide range of co-occurring difficulties (and in some cases associated strengths) these do not reliably distinguish those with dyslexia from other poor readers, and although ‘useful signs’, these are not sufficient on their own to be used as ‘symptoms.’ Elliot and Gibbs (2008) state convincingly that ‘there appears to be no clear-cut scientific basis for differential diagnosis of dyslexia versus poor reader’ (p. 488). Therefore we do not identify dyslexia on the basis of symptoms or ‘positive signs’ (checklists often cite difficulties with letter orientation and letter confusion, poor sequencing skills etc). Dyslexic difficulties should be understood in terms of 2 their severity and persistence in spite of opportunities to learn, and no other features reliably identify this condition. This makes dyslexia the responsibility of all teachers and not just specialists, and urges an early-intervention approach to literacy difficulties, rather than proposing a system where teachers wait for a significant degree of under-achievement and expert diagnosis before applying this label and then implementing measures to remediate the difficulties. Schools have a responsibility to ensure that some teachers in local schools have specialist skills and knowledge regarding methods for teaching children with dyslexic difficulties, and to make effective use of their SEN delegated budget for children with these difficulties. They have a duty to implement advice received from Local Authority support services, organise access arrangements for children with literacy difficulties and to ensure that additional and different provision is consistently in place to meet the needs of children with dyslexic difficulties. Schools need to ask ‘are the child’s dyslexic difficulties so severe and persistent that they require extra resources’ instead of ‘does the child have dyslexia?’ These resources need to be made available early on, at the first signs of a child falling behind, with a process of identification through teaching, by teachers, and where increasing levels of support become directed to resolve the problems. There is an expectation that as the child’s difficulties persist in spite of intervention, that the programme they receive becomes increasingly intense, specialised and individual, with interventions proceeding in three successive ‘waves’ from the whole class to the individual level, described in the SEN Code of practice as a ‘graduated response.’ We recognise the hugely detrimental emotional impact that accompanies dyslexic difficulties in some children and see this as an avoidable outcome if care is taken, and early intervention is successful. We believe that all children can learn to read if given the right opportunities and experiences in spite of dyslexic difficulties. Sadly, we understand that environmental factors can also prevent some children learning to read (including poor teaching, and lack of family support). We recognise that some psychologists and teachers may use other terminology (SpLD, literacy difficulties), however, in Herefordshire we have adopted the definition from the Rose Report and acknowledge these other terms as consistent with this definition. The term ‘dyslexic difficulties’ refers to the reading behaviour rather than the child, or their internal predispositions. Every child is different and comes with a complex and distinct set of experiences and capabilities. Therefore, it is not possible to state how great a child’s delay in literacy needs to be in order to be described as severe. We define severity in terms of how resistant the child’s difficulties are in spite of attempts to remediate and resolve them. We also acknowledge that severity should be understood in terms of how the child’s difficulties interfere with their ageappropriate curriculum access. Explicit systematic phonics teaching to develop word reading skills is the most effective teaching method for pupils with dyslexic difficulties (Brooks, 2007). In addition, the teaching of whole word recognition may be suited to children who struggle with phonics. Furthermore, it is important to acknowledge the importance of developing the motivation to become a thoughtful reader, and recognising that this is enhanced by regular access to interesting, 3 familiar and relevant texts, and through providing children with frequent opportunities to increase their fluency by reading with success alongside someone else. The literacy interventions used should have their effectiveness proven by academic research and include: - an element of phonological training; logical progression of elements with small steps teaching (and not just a collection of unrelated worksheets); regular and frequent reinforcement until learning and retrieval is automatic; skills teaching to enable the burden on working memory to be reduced; multi-sensory approaches and the active integration of auditory, visual, kinaesthetic elements within teaching; success based learning to build self-esteem and eliminate emotional obstacles to learning. Teaching methods remain the same whether or not the word ‘dyslexia’ is used. The IDP materials for dyslexia have been revised in line with the Rose Report and remain a very useful resource for schools and EPs alike: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100202100434/http:/nationalstrategies.stand ards.dcsf.gov.uk/node/175591 The Dyslexia SPLD trust has the support of the Department of Education to provide information for parents and schools on a wide range of topics, and with a range of resources for schools: http://www.thedyslexia-spldtrust.org.uk/ Whilst we recognise that the label dyslexia can provide great support and comfort to those who may have experienced a sense of failure when learning to read, we favour an approach based on supporting schools to identify measures which seek to resolve a child’s literacy difficulties and meet their Special Educational Needs in preference to identification of dyslexia. Over the coming year we hope to develop a coherent set of guidelines, based on research, that outlines exactly what sort of interventions and programmes have the best outcomes for children with dyslexic difficulties. Information for this policy statement was obtained from: Brooks, G. (2007). What Works for Pupils with Literacy Difficulties? The Effectiveness of Intervention Schemes. 3rd edition. London: DCSF. http://www.interventionsforliteracy.org.uk/assets/documents/Greg-Brooks.pdf Elliott, Julian G. & Gibbs, Simon (2008). Does dyslexia exist? Journal of Philosophy of Education 42 (3-4):475-491. Essex Council (2011). Supporting Pupils with Dyslexia 4 http://essexcc.gov.uk/vip8/si/esi/content/binaries/documents/Service_Areas/SENaPS/SEN_P rotocols/FINAL_Dyslexia_policy_pdf_FINAL.pdf Reason, R. & Stothard, J. (2013) ‘Is there a place for dyslexia in educational psychology practice?’ Debate, DECP, 146. Vellutino, F.R, Fletcher, J.M, Snowling, M.J, Scanlon, D.M. Specific reading disability (dyslexia): what have we learned in the past four decades? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004 Jan;45(1):2-40. Review. Access the Rose report at: https://www.education.gov.uk/publications/standard/_arc_SOP/Page7/DCSF-00659-2009 British Psychological Society Definition (BPS, DECP, 1999; reprinted 2005): “Dyslexia is evident when accurate and fluent word reading and/or spelling develops very incompletely or with great difficulty. This focuses on literacy learning at the ‘word level’ and implies that the problem is severe and persistent despite appropriate learning opportunities. It provides the basis for a staged process of assessment through teaching.” (from ‘Dyslexia, Literacy and Psychological Assessment’ British Psychological Society, DECP 1999). Kamran Khan Debbie Chamberlain Jane Mansfield September 2013 Herefordshire Psychology Service 5