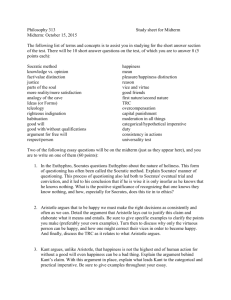

KANT - ARISTOTLE lecture

advertisement

ARISTOTLE AND KANT This lecture is meant to provide you with a little background to better understand the ethical theories of Aristotle and Kant, which turn out to be much closer to each other than the differences in their scientific and philosophic views might lead you to believe. KANT Everything in nature is determined. The body is part of nature. Therefore, everything bodily is determined. (I.e. physical movements, emotions, and desires.) Aristotle and Kant Lecture 2 Thus, Kant can say that our emotions and desires don’t have moral worth because they are not free. The will is NOT part of nature. It is the ability of our reason to form “maxims” or principles of action. The will is free. Hence, it CAN have moral worth precisely because it is free. The will is not part of nature, according to Kant, because it’s part of our rational faculties, which impose order upon the perceptions of the senses, and by “nature” he means the world of the senses, the physical world. This may sound weird, but Kant’s way of thinking is part of a philosophical tradition stemming from Plato, according to which Aristotle and Kant Lecture 3 the physical world is NOT the ultimate reality. In the form in which it appeared in the period in which modern science arose (i.e. since the seventeenth century), Kant’s view is more problematic than Plato’s. In this view the physical world is a vast machine in which everything that happens is determined by the physical laws of nature. Our minds exist, but we don’t know how to connect them with our bodies. Hence, it is called “the mind-body dualism.” Yes, it sounds weird, but is it any weirder than biology professors refusing to say what life is? As Keeton, the author of the biology text I cited might say, “Hey, lemme alone. Aristotle and Kant Lecture 4 I’m a biologist, not a philosopher. How should I know what life is? I’m only a poor biologist.” Perhaps you can see from this example that the mind-body dualism isn’t something that a few obscure philosophers thought up. It pervades our thinking. It pervades our science. Another consequence of this view is that, strictly speaking, animals are just machines. So we can do with them what we want. Now of course, the average person doesn’t believe that, but the average person as well as modern scientists still doesn’t know how to overcome this dualism, and this puts them at a disadvantage when arguing with people Aristotle and Kant Lecture 5 who don’t have scruples about wiping out and otherwise messing up the environment. Hence, when biology came to the fore among the sciences in the nineteenth century with Darwin and others, it had a materialist view of the world that contradicted a more “normal” view of biological organisms in which we tend to regard them as more than just machines. The conclusion you might draw from this is that, despite the wonders of modern science, a lot of modern thinking is confused and self-contradictory. That is a correct conclusion. And for the most part, the “philosophers,” that is, the philosophy Aristotle and Kant Lecture 6 professors, or “professional philosophers” as they often call themselves, share this confusion. ARISTOTLE There is no mind-body dualism in Aristotle and biological organisms are not machines. To say they are “alive,” according to him, means that they have a principle of organization and self-movement called the psyché or “soul.” I put the English word “soul” in quotation marks because it has religious connotations, which Aristotle’s term does not, but it’s the closest word we have in English to translate his term. All Aristotle meant was that the various functions of biological organisms are not separate components of a machine, but that Aristotle and Kant Lecture 7 together they comprise an organic whole that functions as a unity. That unity is very dependent on the different organs of the body that comprise it, so that when the organism dies, in Aristotle’s view, this unity doesn’t survive. The “soul” is the functional unity of the basic bodily functions, and the mind is its highest power. The mind too forms a unity within the overall unity of the soul. Again I emphasize that the mind is a power of the soul, so the two are very closely connected. The mind is the power of the soul by which we think. The brain is the physical organ where the mind is located, but the brain is obviously part of the body and the mind is part of the soul. Hence, to say that we have “free will” (to use the modern term) means Aristotle and Kant Lecture 8 that the mind has the power of thinking and of moving the body. In this brief lecture I won’t go into the details of Aristotle’s explanation of just how the mind thinks, how it moves the body, how Aristotle explains the nature of consciousness, how he avoids the mindbody dualism that has plagued modern philosophy AND modern science, and so on. I trust you will be so kind as to take my word that whether or not his explanation is correct, he does have such an explanation and Kant and the other modern philosophers do not. Hence, Kant has to POSIT free will and the mind’s ability to move the body, but he has no way of explaining it. Of course not—he thinks biological organisms are Aristotle and Kant Lecture 9 really machines! But I don’t want to belabor this point. Aristotle’s Ethics and Kant’s Ethics The bottom line (for our discussion of ethics) is that for Aristotle, unlike Kant, it’s not just the will that is good and moral. Aristotle doesn’t have to define morality strictly in terms of moral laws like the categorical imperative. We can have good emotions and pleasures, and good feelings toward each other, something like the higher pleasures of Mill and Epicurus. Aristotle DOES have moral commands or principles or laws, based on the overarching virtue of justice, but they arise out of our nature as beings possessing reason. In other Aristotle and Kant Lecture 10 words, when we fully realize our nature as animals possessing reason, our emotions and desires and our reason TEND to be in harmony with teach other. The Bottom Line Despite these fundamental differences, based on their underlying scientific and philosophical theories, their ethical theories turn out to have more in common than they are commonly understood to have. For example, consider Kant’s perfect and imperfect duties, or to use his alternative terms for them, strict and meritorious duties. Aristotle’s virtue of justice roughly corresponds to Kant’s perfect or strict duties, and the list of virtues that Aristotle Aristotle and Kant Lecture 11 provides roughly corresponds to Kant’s imperfect or meritorious duties. Hence—here is the shattering conclusion— the behavior or lifestyle that each recommends is fairly similar. That statement immediately has to be qualified a little. For one thing, Kant did not understand Aristotle’s concept of ethical virtue—believe it or not, he never read Aristotle, who was out of favor in the time when Kant lived—but WE can see the similarity, even if Kant himself didn’t. Even brilliant minds like Kant aren’t perfect. On the other hand, we can appreciate Kant’s brilliance more when we see how much he did philosophically with the limited tools he had to work with.