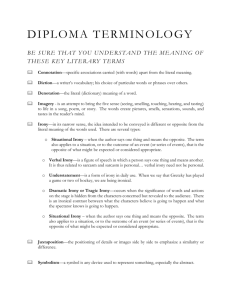

the role of salience-based yet incompatible interpretations in

advertisement

In: L. Cummings (ed.), Pragmatics Encyclopedia. London: Routledge. IRONY Rachel Giora How do we go about interpreting an ironic utterance such as You’re sharp, aren’t you? (Flesh 2004). Given the speaker’s ostensive ironic intent, does that guarantee that we activate the appropriate interpretation initially or even exclusively? Or could the process also involve the literal (‘piercing’) and metaphoric (‘smart’) interpretations of the utterance, regardless of their inappropriateness? An unresolved issue within pragmatics and psycholinguistics is whether our cognitive machinery is adept at swiftly and accurately homing in on a single, contextually appropriate interpretation (Gibbs 1986, 1994; Sperber and Wilson 1986/1995) or whether it is less efficient at sieving out interpretations based on salient (coded and prominent) word and phrase meanings which might be derived irrespective of contextual information and speakers’ intent (Giora 1997, 2003). Within the field of nonliteral language, this translates into whether accessible but incompatible messagelevel interpretations are involved even when contextual information is highly supportive of an alternative interpretation. The debate within irony research thus revolves around the role of salience-based yet incompatible interpretations in shaping contextually compatible ironic but non-salient interpretations in contexts strongly benefiting such interpretations. What kind of contexts may benefit ironic interpretations? On one view, titled ‘the direct access model’ (Gibbs 1986, 1994, 2002), a context displaying some contrast between what is expected (by the protagonist) and the reality that frustrates it, while further conveying negative emotions, will both predict and facilitate ironic interpretations (Colston 2002; Gibbs 1986, 2002: 462; Utsumi 2000). On another view, titled ‘the constraints-based model’, a context involving contextual factors inviting an ironic interpretation (such as speakers known for their nonliteralness) will raise an expectation for an ironic utterance which, in turn, will facilitate irony interpretation exclusively (Pexman et al. 2000). (For a detailed review of the existing models of irony, see Giora 2003: 61-102). However, experiments in which one varies characteristics deemed effective by the direct access or constraints-based models have not demonstrated an increase in irony predictability or observed facilitation of irony interpretation (Giora et al. in press). Although findings in Gibbs (1986) can be viewed as demonstrating similar processing times for ironies and equivalent salience-based (literal) interpretations, they may also be viewed as demonstrating quite the opposite, namely, that irony is more difficult to derive than salience-based interpretations (Dews and Winner 1997; Giora 1995). Another way to induce an expectation for an ironic utterance has been studied by Giora et al. (2007) who increased uses of ironies in contexts preceding ironic targets. Still, while these contexts gave rise to an expectation for another ironic utterance (as might be also envisaged by Kreuz and Glucksberg 1989), this expectation did not facilitate ironical interpretations of those utterances compared to their salience-based (e.g. literal) interpretations. In spite of their contextual inappropriateness, only salience-based interpretations were facilitated initially, even when comprehenders were allowed lengthy (1000 msec) processing time. Another environment privileging ironic interpretation is that shared by intimates who rely on a rich common ground and who are willing to join in the fun (Clark 1996; Clift 1999; Eisterhold et al. 2006; Gibbs 2000; Kotthoff 2003; Pexman and Zvaigzne 2004). However, a check of the way friends respond to their mates’ ironic turns shows that they mostly respond to the salience-based (e.g. literal/‘what is said’) interpretation of the irony, either by addressing it directly or by extending the ironic turn on the basis of the salience-based interpretation (Eisterhold et al. 2006; Giora and Gur 2003; Kotthoff 2003). For instance, the irony cited above (You’re sharp, aren’t you?) is followed by an utterance (I like my men to have “brains” and a “bit of class”) that elaborates on the salient (metaphoric) meaning of the irony. Such response patterns testify to the high accessibility of irony’s salience-based interpretations which may therefore lend themselves to further elaborations. Indeed, most of the behavioural evidence in irony research argues in favour of a salience-based-initial rather than contextually-compatible-initial model of irony interpretation (Colston and Gibbs 2002; Dews and Winner 1999; Giora 1995; Giora and Fein 1999; Giora et al. 1998, 2007, in press; Katz et al. 2004; Katz and Pexman 1997; Ivanko and Pexman 2003; Pexman et al. 2000; Schwoebel et al. 2000). Corpusassisted studies too support the view that salience-based interpretations are highly functional in irony interpretation (Partington 2007). Among other things, it is, in fact, the initial activation of incompatible, salience-based interpretations that makes irony interpretation a complex and error-prone process (Anolli et al. 2001; Lagerwerf 2007), as also demonstrated by some notorious misunderstandings (e.g. taking Swift’s A modest proposal, literally; see Booth 1974). The view that irony interpretation is a complex process also gains support from neurological studies. For instance, irony has been shown to recruit the right hemisphere, which is adept at inferencing and remote associations. Salient meanings and salience-based interpretations (familiar literals and familiar metaphors), however, rely more heavily on the left hemisphere, which reduces the range of possible alternatives to the most salient ones (Eviatar and Just 2006; Giora et al. 2000; Kaplan et al. 1990; McDonald 1999; Peleg and Eviatar 2008; Shamay-Tsoory et al. 2005; Wakusawa et al. 2007). Furthermore, neurologically-impaired populations were also found to fare better on salience-based interpretations than on (non-salient) ironic interpretations. For instance, populations impaired on theory of mind (the ability to distinguish between our own mental states and those of others), such as autistic individuals (including individuals with Asperger syndrome, a high-functioning variant of autism), individuals with closed head injury, brain damage (especially right-hemisphere damage) and schizophrenia performed worse than normal controls on irony compared to familiar (metaphoric and literal) interpretations (Baron-Cohen et al. 1993, 1997; Channon et al. 2005; Giora et al. 2000; Kaland et al. 2005; Kasari and Rotheram-Fuller 2005; Leitman et al. 2006; Martin and McDonald 2004; McDonald 2000; Mitchley et al. 1998; Mo et al. 2008; Stratta et al. 2007; Thoma and Daum 2006; Tompkins and Mateer 1985; Wang et al. 2006; Winner et al. 1998). Developmentally, findings which show that irony acquisition occurs rather late, between 6 and 9 years of age (Bernicot et al. 2007; Creusere 2000; Hancock and Purdy 2000; Winner 1988), and decays earlier than simpler tasks (Bara et al. 2000) also support the view that interpreting irony might be a complex process. And while adults mostly make do with contextual information (Bryant and Fox Tree 2005), children, in addition, often rely on prosodic cues when detecting irony (Ackerman 1981, 1983, 1986; Capelli et al. 1990; de Groot et al. 1995; Milosky and Ford 1997; Winner 1988; Winner et al. 1988; but see Attardo et al. 2003 and Bryant and Fox Tree 2005 who found that there is no specific tone of voice for irony). This diverse array of findings, coupled with observed scarcity (7 to 10 per cent) of ironic turns among friends (Attardo et al. 2003; Eisterhold et al. 2006; Gibbs 2000; Partington 2007; Rockwell 2004; Tannen 1984), elementary-school teachers (Lazar et al. 1989), and others (Haiman 1998; Hartung 1998) and the failures to detect them (Attardo 2002; Rockwell 2004) bring out irony’s complex nature. Such complexity is predicted by theories which assume that salience-based albeit incompatible interpretations play a major role in irony interpretation (Clark and Gerrig 1984; Colston 1997, 2002; Currie 2006; Dews and Winner 1999; Giora 1995; KumonNakamura et al. 1995; Récanati 2004; Sperber and Wilson 1986/1995: 242), while further triggering inferential processes such as implicature derivation (Attardo 2000, 2001; Grice 1975; Carston 2002: 160) and theory of mind (Curcó 2000; Happé 1993, 1995; Sperber and Wilson 1986/1995; Wilson 2006; Wilson and Sperber 1992). Although by the age of 6 years we can distinguish between our own and others’ mental states, even as adults we often fail to recruit this ability initially (Keysar 1994, 2000; Keysar et al. 2003), although this may vary culturally (Wu and Keysar 2007). However, theories assuming that context can effect immediate if not exclusive activation of nonsalient but contextually compatible interpretations (Gibbs 1994; Katz et al. 2004; Pexman et al. 2000; Utsumi 2000) cannot, at this stage, explain a wide range of findings accumulated during the last two decades of irony research. Still, testing the initial effect of a cluster of contextual factors, including their relative weight, might shed further light on the nature of irony interpretation. Suggestions for further reading: Barbe, K. (1995) Irony in Context, Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Gibbs, R.W. Jr. and Colston, H.L. (eds) (2007) Irony in Language and Thought: A Cognitive Science Reader, New York, London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Martin, A.R. (2007) The Psychology of Humor: An Integrative Approach, Burlington, MA: Elsevier. BIBLIOGRAPHY Ackerman, B.P. (1981) ‘Young children’s understanding of a speaker’s intentional use of a false utterance’, Developmental Psychology, 17: 472-80. Ackerman, B.P. (1983) ‘Form and function in children’s understanding of ironic utterances’, Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 35: 487-508. Ackerman, B.P. (1986) ‘Children’s sensitivity to comprehension failure in interpreting a nonliteral use of an utterance’, Child Development, 57: 485–97. Anolli, L., Infantino, M.G. and Ciceri, R. (2001) ‘“You’re a real genius!”: irony as a miscommunication design’, in L. Anolli, R. Ciceri & G. Riva (eds) Say Not to Say: New Perspectives on Miscommunication, Amsterdam: IOS Press. Attardo, S. (2000) ‘Irony as relevant inappropriateness’, Journal of Pragmatics, 32: 793-826. Attardo, S. (2001) Humorous Texts: A Semantics and Pragmatics Analysis, Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter. Attardo, S. (2002) ‘Humor, irony and their communication: from mode adoption to failure of detection’, in L. Anolli, R. Ciceri & G. Riva (eds) Say Not to Say: New Perspectives on Miscommunication, Amsterdam: IOS Press. Attardo, S., Eisterhold, J., Poggi, I. and Hay, J. (2003) ‘Multimodal markers of irony and sarcasm’, HUMOR: International Journal of Humor Research, 16: 243-60. Bara, B.G., Bucciarelli, M. and Geminiani, G.C. (2000) ‘Development and decay of extra-linguistic communication’, Brain and Cognition, 43: 21-7. Baron-Cohen, S., Tager-Flusberg, H. and Cohen, D.J. (eds) (1993) Understanding other Minds – Perspectives from Autism, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Baron-Cohen, S., Jolliffe, T., Mortimore, C. and Robertson, M. (1997) ‘Another advanced test of theory of mind: evidence from very high functioning adults with autism or Asperger Syndrome’, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38: 81322. Bernicot, J., Laval, V. and Chaminaud, S. (2007) ‘Nonliteral language forms in children: in what order are they acquired in pragmatics and metapragmatics?’, Journal of Pragmatics, 39: 2115-32. Booth, W. (1974) A Rhetoric of Irony, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Bryant, G.A. and Fox Tree, J.E. (2005) ‘Is there an ironic tone of voice?’, Language and Speech, 48: 257-77. Capelli, C.A., Nakagawa, N. and Madden, C.M. (1990) ‘How children understand sarcasm: the role of context and intonation’, Child Development, 61: 1824–41. Carston, R. (2002) Thoughts and Utterances, Oxford: Blackwell. Channon, S., Pellijeff, A. and Rule, A. (2005) ‘Social cognition after head injury: sarcasm and theory of mind’, Brain and Language, 93: 123-34. Clark, H.H. (1996) Using Language, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Clark, H.H. and Gerrig, R. (1984) ‘On the pretense theory of irony’, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 113: 121-26. Clift, R. (1999) ‘Irony in conversation’, Language in Society, 28: 523–53. Colston, H.L. (1997) ‘Salting a wound or sugaring a pill: the pragmatic functions of ironic criticism’, Discourse Processes, 23: 25-45. Colston, H.L. (2002) ‘Contrast and assimilation in verbal irony’, Journal of Pragmatics, 34: 111-42. Colston, H.L. and Gibbs, R.W. Jr. (2002) ‘Are irony and metaphor understood differently?’, Metaphor and Symbol, 17: 57-80. Creusere, M.A. (2000) ‘A developmental test of theoretical perspectives on the understanding of verbal irony: children’s recognition of allusion and pragmatic insincerity’, Metaphor and Symbol, 15: 29-45. Curcó, C. (2000) ‘Irony: negation, echo and metarepresentation’, Lingua, 110: 25780. Currie, G. (2006) ‘Why irony is pretence’, in S. Nichols (ed.) The Architecture of the Imagination, Oxford: Oxford University Press. de Groot, A., Kaplan, J., Rosenblatt, E., Dews, S. and Winner, E. (1995) ‘Understanding versus discriminating nonliteral utterances: evidence for a dissociation’, Metaphor and Symbol, 10: 255–73. Dews, S. and Winner, E. (1997) ‘Attributing meaning to deliberately false utterances: the case of irony’, in C. Mandell & A. McCabe (eds) The Problem of Meaning: Behavioral and Cognitive Perspectives, Amsterdam: Elsevier. Dews, S. and Winner, E. (1999) ‘Obligatory processing of the literal and nonliteral meanings of ironic utterances’, Journal of Pragmatics, 31: 1579-99. Eisterhold, J., Attardo, S. and Boxer, D. (2006) ‘Reactions to irony in discourse: evidence for the least disruption principle’, Journal of Pragmatics, 38: 1239-56. Eviatar, Z. and Just, M. (2006) ‘Brain correlates of discourse processing: an fMRI investigation of irony and metaphor comprehension’, Neuropsychologia, 44: 2348-59. Flash (2004) Big Dopes with High Hopes. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.abctales.com/node/506844 (accessed 13 September 2004). Gibbs, R.W. Jr. (1986) ‘On the psycholinguistics of sarcasm’, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 115: 3-15. Gibbs, R.W. Jr. (1994) The Poetics of Mind, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Gibbs, R.W. Jr. (2000) ‘Irony in talk among friends’, Metaphor and Symbol, 15: 5-27. Gibbs, R.W. Jr. (2002) ‘A new look at literal meaning in understanding what is said and implicated’, Journal of Pragmatics, 34: 457-86. Giora, R. (1995) ‘On irony and negation’, Discourse Processes, 19: 239-64. Giora, R. (1997) ‘Understanding figurative and literal language: the graded salience hypothesis’, Cognitive Linguistics, 7: 183-206. Giora, R. (2003) On our Mind: Salience, Context and Figurative Language, New York: Oxford University Press. Giora, R. and Fein, O. (1999) ‘Irony: context and salience’, Metaphor and Symbol, 14: 241-57. Giora, R., Fein, F., Kaufman, R., Eisenberg, D. and Erez, S. (in press) ‘Does an ‘ironic situation’ favor an ironic interpretation?’, in G. Brône & G. Vandaele (eds) Cognitive Poetics, Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter. Giora, R., Fein, O., Laadan, D., Wolfson, J., Zeituny, M., Kidron, R., Kaufman, R. and Shaham, R. (2007) ‘Expecting irony: context vs. salience-based effects’, Metaphor and Symbol, 22: 119-46. Giora, R. and Gur, I. (2003) ‘Irony in conversation: salience and context effects’, in B. Nerlich, Z. Todd, V. Herman & D.D. Clarke (eds) Polysemy: Flexible Patterns of Meanings in Language and Mind, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. Giora, R., Fein, O. and Schwartz, T. (1998) ‘Irony: graded salience and indirect negation’, Metaphor and Symbol, 13: 83-101. Giora, R., Zaidel, E., Soroker, N., Batori, G. and Kasher, A. (2000) ‘Differential effects of right and left hemispheric damage on understanding sarcasm and metaphor’, Metaphor and Symbol, 15: 63-83. Grice, H.P. (1975) ‘Logic and conversation’, in P. Cole & J. Morgan (eds) Syntax and Semantics 3: Speech Acts, New York: Academic Press. Haiman, J. (1998) Talk is Cheap: Sarcasm, Alienation, and the Evolution of Language, New York: Oxford University Press. Hancock, J.T. and Purdy, K. (2000) ‘Children’s comprehension of critical and complimentary forms of verbal irony’, Journal of Cognition and Development, 12: 227-40. Happé, G.E.F. (1993) ‘Communicative competence and theory of mind in autism: a test for relevance theory’, Cognition, 48: 101-19. Happé, G.E.F. (1995) ‘Understanding minds and metaphors: insights from the study of figurative language in autism’, Metaphor and Symbolic Activity, 10: 275-95. Hartung, M. (1998) Ironie in der Alltagssprache, Opladen/Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag. Ivanko, L.S. and Pexman, M.P. (2003) ‘Context incongruity and irony processing’, Discourse Processes, 35: 241-79. Kaland, N., Møller-Nielsen, A., Smith, L., Mortensen, E.L., Callesen, K. and Gottlieb, D. (2005) ‘The Strange Stories test: a replication study of children and adolescents with Asperger syndrome’, European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 14: 73-82. Kaplan, J.A., Brownell, H.H., Jacobs, R.J. and Gardner, H. (1990) ‘The effects of right hemisphere damage on the pragmatic interpretation of conversational remarks’, Brain and Language, 38: 315-33. Katz, N.A., Blasko, G.D. and Kazmerski, A.V. (2004) ‘Saying what you don’t mean: social influences on sarcastic language processing’, Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13: 186-89. Katz, A.N. and Pexman, P. (1997) ‘Interpreting figurative statements: speaker occupation can change metaphor into irony’, Metaphor and Symbolic Activity, 12: 1941. Kasari, C. and Rotheram-Fuller, E. (2005) ‘Current trends in psychological research on children with high-functioning autism and Asperger disorder’, Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 18: 497–501. Keysar, B. (1994) ‘The illusory transparency of intention: linguistic perspective taking in text’, Cognitive Psychology, 26: 165-208. Keysar, B. (2000) ‘The illusory transparency of intention: does June understand what Mark means because he means it?’, Discourse Processes, 29: 161-72. Keysar, B., Lin, S. and Barr, D.J. (2003) ‘Limits on theory of mind use in adults’, Cognition, 89: 25-41. Kotthoff, H. (2003) ‘Responding to irony in different contexts: cognition and conversation’, Journal of Pragmatics, 35: 1387-1411. Kreuz, R. and Glucksberg, S. (1989) ‘How to be sarcastic: the echoic reminder theory of verbal irony’, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 118: 374–86. Kumon-Nakamura, S., Glucksberg, S. and Brown, M. (1995) ‘How about another piece of the pie: the allusional pretense theory of discourse irony’, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 124: 3-21. Lagerwerf, L. (2007) ‘Irony and sarcasm in advertisements: effects of relevant inappropriateness’, Journal of Pragmatics, 39: 1702–21. Lazar, R.T., Warr-Leeper, G.A., Nicholson, C.B. and Johnson, S. (1989) ‘Elementary school teachers’ use of multiple meaning expressions’, Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 20: 420-30. Leitman, D.I., Ziwich, R., Pasternak, R. and Javitt, D.C. (2006) ‘Theory of mind (ToM) and counterfactuality deficits in schizophrenia: misperception or misinterpretation?’, Psychological Medicine, 36: 1075-83. Martin, I. and McDonald, S. (2004) ‘An exploration of causes of non-literal language problems in individuals with Asperger Syndrome’, Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34: 311-28. McDonald, S. (1999) ‘Exploring the process of inference generation in sarcasm: a review of normal and clinical studies’, Brain and Language, 68: 486–506. McDonald, S. (2000) ‘Neuropsychological studies of sarcasm’, Metaphor and Symbol, 15: 85-98. Milosky, L.M. and Ford, J.A. (1997) ‘The role of prosody in children’s inferences of ironic intent’, Discourse Processes, 23: 47-61. Mitchley, N.J., Barber, J., Gray, J.M., Brook, D.N. and Martin, G.L. (1998) ‘Comprehension of irony in schizophrenia’, Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 3: 127-38. Mo, S., Su, Y., Chan, R.C.K. and Liu, J. (2008) ‘Comprehension of metaphor and irony in schizophrenia during remission: the role of theory of mind and IQ’, Psychiatry Research, 157: 21–29. Partington, A. (2007) ‘Irony and reversal of evaluation’, Journal of Pragmatics, 39: 1547-69. Peleg, O. and Eviatar, Z. (2008) ‘Hemispheric sensitivities to lexical and contextual information: evidence from lexical ambiguity resolution’, Brain and Language, Pexman, P.M., Ferretti, T. and Katz, N.A. (2000) ‘Discourse factors that influence irony detection during on-line reading’, Discourse Processes, 29: 201-22. Pexman, P.M. and Zvaigzne, T.M. (2004) ‘Does irony go better with friends?’, Metaphor and Symbol, 19: 143-63. Récanati, F. (2004) Literal Meaning, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Rockwell, P. (2004) ‘Differences in participants’ estimates and identification of their own and their partners’ sarcastic utterances’, Journal of Diplomatic Language. Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.jdlonline.org/I4Rockwell1.html> (accessed 3 December 2007). Schwoebel, J., Dews, S., Winner, E. and Srinivas, K. (2000) ‘Obligatory processing of the literal meaning of ironic utterances: further evidence’, Metaphor and Symbol, 15: 47-61. Shamay-Tsoory, S.G., Tomer, R. and Aharon-Peretz, J. (2005) ‘The neuroanatomical basis of understanding sarcasm and its relationship to social cognition’, Neuropsychology, 19: 288–300. Sperber, D. and Wilson, D. (1986/1995) Relevance: Communication and Cognition, Oxford: Blackwell. Stratta, P., Riccardi, I., Mirabilio, D., Di Tommaso, S., Tomassini, A. and Rossi, A. (2007) ‘Exploration of irony appreciation in schizophrenia: a replication study on an Italian sample’, European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 257: 337-9. Tannen, D. (1984) Conversational Style, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Thoma, P. and Daum, I. (2006) ‘Neurocognitive mechanisms of figurative language processing: evidence from clinical dysfunctions’, Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 30: 1182–1205. Tompkins, C.A. and Mateer, C.A. (1985) ‘Right hemisphere appreciation of prosodic and linguistic indications of implicit attitude’, Brain and Language, 24: 185–203. Utsumi, A. (2000) ‘Verbal irony as implicit display of ironic environment: distinguishing ironic utterances from nonirony’, Journal of Pragmatics, 32: 17771807. Wakusawa, K., Sugiura, M., Sassa, Y., Jeong, H., Horie, K., Sato, S., Yokoyama, H., Tsuchiya, S., Inuma, K. and Kawashima R. (2007) ‘Comprehension of implicit meanings in social situations involving irony: a functional MRI study’, Neuroimage, 37: 1417-26. Wang, A.T., Lee, S.S., Sigman, M. and Dapretto, M. (2006) ‘Neural basis of irony comprehension in children with autism: the role of prosody and context’, Brain, 129: 932–43. Wilson, D. (2006) ‘The pragmatics of verbal irony: echo or pretence?’, Lingua, 116: 1722-43. Wilson, D. and Sperber, D. (1992) ‘On verbal irony’, Lingua, 87: 53-76. Winner, E. (1988) The Point of Words: Children’s Understanding of Metaphor and Irony, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Winner, E., Brownell, H.H., Happé, G.E.F., Blum, A. and Pincus, D. (1998) ‘Distinguishing lies from jokes: theory of mind deficits and discourse interpretation in right hemisphere brain-damaged patients’, Brain and Language, 62: 89–106. Winner, E., Levy, J., Kaplan, J. and Rosenblatt, E. (1988) ‘Children’s understanding of nonliteral language’, Journal of Aesthetic Education, 22: 51-63. Wu, S. and Keysar, B. (2007) ‘The effect of culture on perspective taking’, Psychological Science, 18: 600-606.