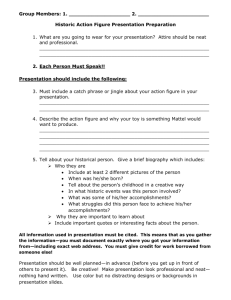

Historic Districts for the Internet

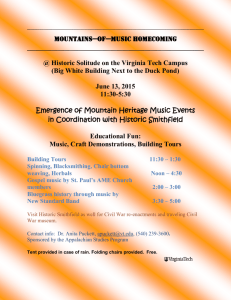

advertisement