An Empirical Assessment of NYPD`s “Operation Impact”

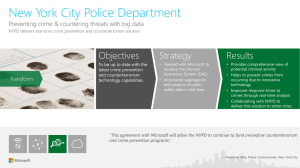

advertisement