Thesis Abstract

advertisement

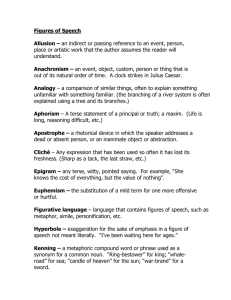

The Uses of Metaphor in Philosophy Liora Barash [Ph.D. Dissertation, Tel Aviv University, 1990] [Supervisor: Marcelo Dascal] ABSTRACT This study purports to establish the legitimacy of the usage of verbal metaphor in all kinds of contexts — scientific, poetic, rhetoric or other —from the reader’s point—of-view, on grounds which originate from contemporary discussions of metaphor, but are original and distinctly different from them. Throughout the history of philosophy there were protagonists and antagonists of the usage of metaphor in scientific and philosophic writings. However, the current study ‘is by no means an historical analysis of the concept of metaphor. Rather, it focuses on a critical survey of the present state—of—the—art, which is characterized by an ongoing dialogue between the various schools of thought — on the one hand; and by vast controversies — on the other. On the basis of this critical survey, the study aims to substantiate a different conception for a theory of language, which enables to prove three major conclusions: 1. The cognitive status of metaphor as a unique mode of indirect language—use, being both identifiable and understandable and as such neither substitutable nor exchangeable. 2. It establishes an unequivocal criterion for the distinction of metaphor from all other modes of language—use: myth; simile and analogy; meaningless, false or irrelevant statements; indirect speech acts, conversational implicatures and ironies; metonymy, synecdoche, oxymoron or paradox; scientific model etc. 3. It substantiates the advantages of this analysis over other modern theories of metaphor. These conclusions are provable provided the following conditions are satisfied: 1. The reader’s point of view is distinguished from the speaker’s point of view. 2. From the reader’s point of view, metaphor, as well as any other mode of language—use, is discernible only under context relevant conditions; 3. The cognitive status of metaphor cannot be arbitrarily predetermined, without taking account of the procedure of its identification and interpretation. 4. The identification of metaphor, as well as of any other mode of language—use, precedes its understanding or interpretation, and is relevant to this purpose; 5. The relevant conditions for the identification and interpretation of metaphor, as well as of any other mode of language—usage, are clearly defined. These conditions are satisfiable provided the following terms for a theory of language are accepted: 1. Semantic aspects of language-meaning and pragmatic aspects of language-use are diagnosed as being both distinct and inter-related: semantics always refers to the literal meaning of a sentence (or other linguistic expression), whereas pragmatics relates to the speaker’s meaning; 2. Both semantics and pragmatics are controlled by rules, although of different kinds: semantics — by algorithmic rules, as opposed to the heuristic rules which govern pragmatics. 3. The understanding of the literal—meaning of a statement takes precedence over the detection of either indirectness or directness, which in turn takes precedence over the discernment of the speaker’s—intention, and is relevant to their discernment. The former are identifiable according to the detection or non—detection of a gap between the statement’s—meaning and the utterance—context respectively; The latter allows for the identification of the sort of mismatch between the statement’s meaning and the speaker’s intention. 4. Utterance—meaning is differentiated from speaker’s—utterance—meaning and takes precedence over it. The former allows for the identification of the mode of language—use, according to the determination of the relationship between the speaker’s—intention and the statement’s -- __ literal—meaning. The latter, however, provides for the interpretation of the utterance, in accordance with the speaker’s—intention. The above mentioned terms for a theory of language are acceptable provided the following assumptions are substantiated: 1. The principle of parsimony applies to the modes of language—usage, and thus serves as the modus—operandi of language. 2. All kinds of writings — philosophic, scientific, poetic, rhetoric or other — are dependent for their understanding on the same modes of language—use. 3. Determining the function of the use of language prior both to identifying the mode of language—use and to its interpretation is tantamount to putting the cart before - the horses: It undermines any attempt to determine the function of any use of-language. 4. The role of the reader is constitutive rather than passive, in any verbal situation. 5. The principle of cooperation applies to any communicative situation. In order to prove its three above mentioned major conclusions, the study is divided into two parts, each sub—divided into two chapters: Part I aims to establish the grounds for determining the adequate theoretical framework for the discussion of metaphor, on the basis of a critical survey of the present state—of—the—art. Part II is dedicated to establishing the uniqueness of the usage of verbal metaphor as well as the legitimacy of it’s use in all kinds of contexts from the reader’s viewpoint, based on the determination of the relevant conditions for the identification and understanding of metaphor, as well as any other mode of language—usage. Part I systematically scrutinizes five schools of thought, representing the present state—of—the—art: The Preference School; the Reductionist School; the Emotive School; the Interactionist School; and the Pragmatic School. These five schools are classified in two categories of approaches to metaphor: The Non—Constructivist, which comprises the first three schools of metaphor mentioned above; and the Constructivist, which consists of the last two schools. This classification is based on two different points of departure implicit in these approaches: The Non—Constructivist approach conditions the cognitive status of metaphor at the outset on extra—linguistic assumptions, which the discussion of metaphor is then supposed to substantiate; The Constructivist approach attempts to probe the cognitive status of metaphor per se, within the framework of either a semantic interactionist conception of a theory of language or a pragmatic conception of it. These criteria for the categorization of the various schools into the above categories are initially presented as a working—hypothesis. However, not only is the working—hypothesis subsequently proven founded, but it is also shown to be essential to determining adequate grounds for the theoretical framework for the discussion of metaphor. Every one of the five schools under discussion is presented both in its general form, and as manifested in particular theories, each being carefully. analyzed and criticized. The Non—Constructivist approach is illustrated by: (a) The Preference School, which assigns a privileged cognitive status to metaphor, for its’ ability to contribute to the perception of constantly changing reality, with which literal language is not designed to cope. This school is exemplified by both the Supervenience Theory, and the Intuitionist Theory. (b) The Reductionist School, which argues that metaphor is reducible —whether in practice or in theory — to either simile or analogy, and is therefore cognitive, is exemplified by the Comparison Theory, by the Literal Simile Theory, and by the Icon Theory. (c) The Emotive School, which views metaphor as a means to express emotions and attitudes and to arouse them in others, is demonstrated by two Emotive Theories, one of which claims the emotive meaning of metaphor to be the other aspect of a two sided “total condition” and affirms its usage in philosophic and scientific writings; and the other which due to metaphor’s emotive meaning, opposes its use in the above mentioned contexts. The Constructivist Approach is represented by: (a) The Interactionist School, which claims an additional level of semantic meaning — the connotative meaning — and on these grounds attempts to establish the cognitive status of metaphor. This school is exemplified by three theories: The Controversy Theory, which is proven to be au intermediate theory still “rooted” in the Non—Constructivist Approach while its aspirations lie in the framework of the Constructivist Approach; the Tension Theory, designating in fact the transition from the former approach to the latter; and the Interaction Theory, which indicates the beginning of the new Pragmatic School. (b) The Pragmatic School, which distinguishes between the pragmatic and semantic aspects of language use, but fails to explain satisfactorily their inter—relations. It is represented by the two theories: The Speech Acts Theory and the Pragmatic Literal Theory, which shares the Speech Acts Theory’s criticism of the Interactionist School, yet opposes its pragmatic arguments. The rather extensive critical survey of the Non—Constructivist theories lends itself not only to the understanding of their wide controversies, but also to the discernment of their common features, as well as their deficiencies. It is made clear that the Contructivist theories attempt, each in their own way, to overcome these deficiencies. Subsequently, it is made possible to discern the common features of the Constructivist approach, and to draw a comparison between the two different approaches. On these grounds the working—hypothesis, relating the differentiation of the above mentioned basic approaches to the debatable question of the legitimacy of the usage of metaphor in scientific and philosophical writings, is considered well—founded. Its essentiality, however, is confirmed only by the understanding of the role the two distinguishable approaches play in determining the adequate framework for a theory of language. Part II initially strives to identify the common assumptions of both the Non-Constructivist and the Constructivist approach, rather than underline their differences. These common assumptions are aimed to serve as points of departure for a language-use theory. This theory precludes the difficulties of both the Non-Constructivist and Constructivist approaches —on the one hand; and overcomes other difficulties — on the other. Accordingly, at the outset of the second part special attention is devoted to identifying “the focal stumbling block on the way” of all theories under discussion, whether Non-Constructivist or Constructivist. It is found to be concealed in one particular assumption, which stems from various sources, but is implicit in all the theories: “The negligibility of the difference between the speaker’s and the reader’s points of view.” This assumption leads the theories astray, obstructs their efforts, and ultimately preempts the theories from any prospect of understanding not only the metaphorical mode of language-use, but also its literal use. Thus, under the assumption of the difference of the two points of view — the speaker’s and the reader’s — on the one hand, and the Cooperative Principle — on the other, the study strives to determine the common assumptions of both approaches — the Non-Constructivist and Constructivist — compatible with the two above mentioned assumptions. These common assumptions serve as points of departure for the discussion of the understanding of the use of metaphor from the reader’s point of view, within the framework of a comprehensive communicative theory of language. It is then demonstrated that from the reader’s point of view metaphor, as well as any other mode of language-usage, is first identified and then interpreted according to relevant conditions: Metaphor, like any other mode of language—use, is identified at the level of utterance—meaning, as opposed to the level of sentence meaning. In contrast to all theories previously discussed, the study argues that the sentence’s literal meaning cannot allow for the identification of metaphor, but rather lends itself to the detection of a gap between the sentence meaning and its utterance context, which allows for the determination of indirectness; which in turn enables the discernment of the speaker’s intention. It is only on the basis of the understanding of the relation between the speaker’s intention and the sentence’s literal meaning that the metaphor is identifiable as one of the modes of indirectness. As such it is distinguishable from other modes of indirectness — conversational implicature, indirect speech acts and irony. The study goes on to demonstrate the advantages of the proposed thesis, based on the distinction between semantic and pragmatic aspects of language usage and their interaction, in comparison with the previously analyzed theses. The identification of a metaphorical utterance of a literal statement also leads to the discernment of the fundamental—principles and mechanisms, which serve the reader in determining the strategy of interpreting the meaning of the utterance in accordance with the speaker’s intention, as identified by the reader. This strategy relies on a “Game of Aspects” — the relevant “moves”, which enable the reader to interpret the utterance in accordance with the speaker’s intention, as identified by the reader. It is described as a sequential procedure of aspect—seeing, throughout which the reader is in a position to define for himself the relevant questions, and answer them accordingly. The controlled procedure of processing the literal meaning from the point of view of speaker’s intention enables the reader to understand metaphor as a unique mode of language-use. Unlike any other mode of language use, metaphor’s processing allows the reader not only the interpretation of both its “frame” and “focus” from well defined aspects, but also the finding of a concealed interpreted “vehicle”, which is projected on its “frame”, thus seen from the aspect of the “vehicle”. As such metaphor is neither replaceable nor exchangeable, but is rather a distinctive cognitive mode of language-use. To conclude this first chapter of the second part of the study, special attention is devoted to examining the advantages of the proposed thesis over the Non—Constructivist approach, the Constructivist approach, as well as additional relevant modern theories. The proposed thesis has seven major advantages over the previously mentioned theories: 1. It establishes the cognitive status of metaphor as a unique mode of language—use, which is both identifiable and understandable. 2. It distinguishes between descriptive and prescriptive aspects of the discussion of metaphor, and confines itself exclusively to the descriptive level. 3. Its adherence to the reader’s point of view lends itself to revealing the relevant conditions whereby the interaction process between the reader and the speaker is materialized. 4. It contributes to the understanding of any mode of language—use, both in establishing the precedence of the identification of the mode of language—use over attempts to its interpretation; in establishing the precedence of the literal meaning over any attempt to detect both indirectness and directness, and to discern the speaker’s intention; in establishing the distinction between utterance meaning and speaker’s utterance meaning, which is essential for the understanding of the processing of language; and in the discernment of the controlled exploitation of various techniques and non—algorithmic rules. 5. It enables the detection of the roots of the vagueness involved in the various current discussions of metaphor — on the one hand; and provides means to considerably reduce the vagueness involved in the understanding of the use of metaphor in all kinds of contexts — on the other. 6. It provides for a distinct discernment of possibilities for controlled exploitation, of aspects of the psychology of emotion and imagination in the process of understanding the use of language. These aspects are shown to be “harnessed”, rather than unattached, to the process of understanding the use of language. 7. It allows for a consistent and systematic analysis of the process of metaphor understanding in a manner complying with assumptions already demonstrated to be shared by the various theories — on the one hand, and -on the other — complementing aspects previously not discerned. The Second Chapter of this part debates the issue of the legitimacy, if at all, of the use of verbal metaphor in all kinds of contexts, philosophical and scientific writings included. The study strives to disprove the arguments of the antagonists of the use of metaphor in philosophical and scientific contexts: 1. The study proves that these arguments are based on the myth of the distinction of the language of science from the language of poetry, as though they were two different languages disposing of two distinct modes for the use of language. 2. It demonstrates how this assumption of the distinction between the two languages leads these theories astray, and accounts for their incoherence. 3. It further shows that the above mentioned arguments do not serve the purpose for which they were designed. The study then proceeds to expose the failures of other metaphor’s defenders. They are shown to be misled by their misconceptions not only regarding the process of metaphor’s understanding, but also in their preconceptions of its functions. Thus, metaphor’s protagonists intensify the vagueness surrounding it and further reinforce its antagonists’ arguments. Finally, from the reader’s point of view the study formulates its own argument for the legitimacy of the use of verbal metaphor in all kinds of contexts, philosophic and scientific writings included, based on the assumption of language’s parsimony in all its modes of language-use; under the assumption of. the uniqueness of metaphor as an identifiable and understandable mode of language-usage; metaphor is proven to be an indispensable mode of language-use, which allows the speaker to motivate the reader to detect a problem and to find its solution, by way of reexamining various levels of both contextual and extra-textual information, in order to solve whatever he finds problematic. The study further argues that any additional function — e.g., aesthetic, intimacy creating, or any other psycho-linguistic or socio-linguistic — metaphor might serve is dependent upon its understanding as a unique mode of language-use. Thus the cycle will have revolved its full circle towards a better understanding of metaphor’s uniqueness as a mode of language-use and thereby of other modes of language-use within the comprehensive framework of a theory of language understanding from the reader’s point of view.