Roaring Twenties Overview Essay - Dorman-Data

advertisement

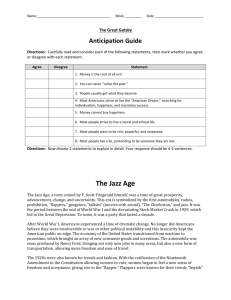

The Roaring Twenties The Jazz Age was just one of many names used to describe the popular culture and newfound prosperity of the United States after World War I. Some have referred to it as the Roaring Twenties, while others have named it the Ballyhoo Years. Each label implies a certain degree of excess. In part, it was a self-indulgent and extravagant reaction to the hardship and austerity experienced during the war. When one speaks of the Jazz Age, what comes to mind is a decade of partying, of the Charleston and jazz bands, of female flappers and loose morals, of bathtub gin and speakeasies, all combined and intertwined into a celebration of American technology and ingenuity that, over the course of a decade, provided average U.S. families the materialistic conveniences of automobiles and modern appliances. Indeed, in many regards, the Jazz Age was an era of abundance and experimentation. Nevertheless, scholars have since debated and questioned the truth of that interpretation, particularly the extent to which the period's much-vaunted prosperity was enjoyed and, indeed, understood by all aspects of U.S. society. Did the 1920s truly roar? Or was it nothing more than a freewheeling binge that would feed into the resultant hangover of the Great Depression in the following decade? Novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald first penned the term "Jazz Age." Though Fitzgerald never ranked among the bestselling authors of the 1920s—Americans were more attuned to the less serious works of Edgar Rice Burroughs and Zane Grey—he was among the first to praise the postwar era for its youthful exuberance in experimenting with new forms of recreation and sexuality. That observation, to some extent, was true. During the Jazz Age, the older generation became increasingly shocked by the younger generation's new morals and manners. From novels and magazines by authors like Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, and Sinclair Lewis, young people were increasingly being associated with wild parties, illicit drinking, roadhouses, and promiscuous behavior. Those new writers defied the old Victorian virtues of womanhood and in their place, promoted the feelings and values of the "flapper girl," who not only sported heavy makeup, bobbed hair, and skirts above the ankles but also drank beer, smoked cigarettes, and drove automobiles. It was an era in which the modernist began to supplant the traditionalist. While traditionalists saw modernism as nothing more than a passing fad, modernists believed that the prevailing Victorian attitudes of the older generation had stifled self-expression and creativity. As excesses go, the Jazz Age was certainly marked by a huge increase in consumerism. Leading the way was the increasing popularity of the automobile, a product that stimulated the U.S. economy more than any other industry. At the turn of the 20th century, there had been only 8,000 automobiles registered in the United States. By 1920, there were 8 million and by the close of the decade, 23 million. With that astonishing rise in popularity came urban sprawl and the economic necessity of owning a car. A more positive aspect, however, was that millions of Americans could now vacation by automobile, thus ending the monopoly of leisure travel by the well-heeled upper classes. Henry Ford's dream of a motorcar for the masses had, by the 1920s, been realized. Cars were more popular than telephones and, in farm households, more popular than running water. As one farm wife explained, "You can't go to town in a bathtub." Automobiles were not the only success story of American marketing. The speed with which the products of mass production spread throughout the United States was alarming; a full array of inventions and technologies dramatically transformed the domestic household. The 1920s were the decade of consumer appliances powered by electricity: electric stoves, sewing machines, vacuum cleaners, dishwashers, washing machines, mixers, toasters, irons, hot-water heaters, space heaters, and refrigerators all appeared and gained popularity. With new inventions, new technologies, and the freedom of automobile travel, Americans were more able to enjoy an affluent and leisurely lifestyle than in any previous time. New forms of entertainment soon emerged. Some of the most notable popular music in U.S. history came out of the 1920s. From the rural and workingclass blues of the South and Midwest came jazz, born in New Orleans among African-American musicians who worked the city's nightlife. From there, it migrated to St. Louis and Chicago, and then to New York and the West Coast. Emphasizing accent and beat over melody, the tom-tom rhythms of Jelly Roll Morton and Louis Armstrong were designed for dancing as well as serious listening—a notable turn from the lyrical melodies of The Roaring Twenties Tin Pan Alley. Though adopted by white bandleaders like Paul Whiteman, whose interpretations were less radical and more structured, jazz music was nonetheless viewed by those traditionalists of puritanical bent as exerting a corrupting influence on the morals of youth. Such conservatives even believed that it was turning young women to prostitution. The Jazz Age was also a golden era for spectator sports, new heroes, and the cinema. As increasingly urban Americans no longer had as much opportunity to participate in sports, their wealth and concentration within the larger cities made professional sports both popular and profitable. It was the era of sports heroes: baseball's Babe Ruth; football's Red Grange and Knute Rockne; boxing's Jack Dempsey and Gene Tunney; and golf's Bobby Jones. America seemed to yearn for heroes, and none was more revered than Charles Lindbergh, who was the first person to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. Another hero, American swimming sensation Johnny Weismuller, was able to translate his success to the cinematic role of Tarzan. In that respect, the U.S. motion picture industry was instrumental in reflecting both American culture and personalities, whether through the device of newsreels or feature films. Though slapstick and homespun silent movies had prospered since 1910, films of the 1920s became increasingly sensational in their presentation. Hollywood producers caught on to the notion that sex sold films, and demure stars like Mary Pickford fell to the sexier images of Jean Harlow, Mae West, Clara Bow, and Greta Garbo. Yet most significantly, the introduction of Al Jolson's The Jazz Singer (1927) ushered in the era of the talkies and marked the end of the silent film. Both rich and poor lined up to see the fantasies Hollywood had to offer. The promotion of all those leisurely activities was unprecedented. During the Jazz Age, the American public became inundated with media inducements to participate in the new era of ballyhoo and prosperity. The giant conglomerates of newspapers, magazines, and radio stations being built by William Randolph Hearst and others contributed to the new fervor for American products and amusements. Whereas almost no one owned a radio in 1920, by the end of the decade, almost everyone did. Radio was the first truly mass form of entertainment, unlike anything previously experienced. The decade also witnessed the rise of tabloid journalism, where tawdry affairs, murders, and scandals stole the headlines from the more serious affairs of statecraft and world politics. Consequently, the sustained advertising of this new seemingly prosperous culture did foster a new sense of values. Yet in the end, all of those developments proved to be nothing more than popular surface manifestations of deeper ills. To truly understand the 1920s requires a longer and deeper systemic view of the era. In the aftermath of World War I, transformation had swept U.S. industries that were reaping the rewards of mass mechanization, the assembly line, electrification, refrigeration, and indoor plumbing. Wearied and disillusioned by the results of a prolonged and costly war, Americans turned inward and seemed consumed with their own prosperity. President Calvin Coolidge proclaimed that the business of the American nation was business itself. Business management was continually streamlined and rationalized, and the value of manufactured products soared to record heights, three times greater than that of agricultural goods. Though the gospel of efficiency prevailed, so did the growing and dangerous practice of overcapitalization and new risky forms of investment. The extent to which the values and prosperity of the Jazz Age culture percolated down through all aspects of U.S. society is debatable. Writing from the close perspective of 1931, Frederick Lewis Allen in Only Yesterday, a popular history of the 1920s, alluded to the inequities and disappointments of a decade in which the much ballyhooed values and material benefits of Jazz Age culture had failed to seep into America proper. Under the surface, there were indications of social and economic malaise throughout the decade. Although Americans enjoyed the world's highest standard of living throughout the 1920s, there were sufficient impediments to economic prosperity. Incomes, while they improved at an unprecedented rate for the middle and upper classes, failed to do so for the millions who still lived in poverty, many of them crowded into city The Roaring Twenties tenements or farm shacks without electricity or running water. Much of the prosperity was limited to middleand upper-class city dwellers, particularly in the North. The Jazz Age also made few inroads into the South, a region that, more than any other, felt keenly the decline of its farms and small towns. At the bottom of the economic ladder were African Americans and other minorities, whose poverty, regardless of locale, was often chronic. Although there was no systematic effort to collect national data on the extent of unemployment, the records of public welfare departments indicate that conditions requiring relief were increasing substantially throughout the 1920s. Nor was the decade one of social enlightenment. The Sacco and Vanzetti trial and execution struck a blow against civil liberties. Moreover, a nationwide resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan and the growth in popularity of eugenics, a "science" that asserted the superiority of whites and their right to rule "lesser races," marked the decade as one of American nativist impulses and bigotry. The lynching of African Americans in the South was still rampant and linked directly to the capitalist aims of the South's economic leaders. The latter's demand for cheap agricultural labor kept both black and white lower-class workers in a state of peonage. Only by inciting racial prejudice between the two—a practice that provoked the lynch mob—did white employers keep their workforce in check. Women, despite their much-vaunted sexual liberation as portrayed in the movies and magazines, remained gender segregated, underpaid, and politically isolated. What made the Jazz Age different from any previous era was that it marked the arrival in force of mass culture—a popular culture that was shaped by mass production, mass consumption, and mass media. It was a culture where white millionaires, factory workers, debutantes, professors, and gangsters could all cram into the nightclubs and movie palaces of America's great cities to see the films of Harlow and West, or to hear the strains of Armstrong and Duke Ellington. However, it was not a culture or prosperity that was to be enjoyed, or indeed appreciated, by all. The capitalistic excesses of the 1920s would ultimately feed and, arguably, shape the depressed conditions of the decade that was to follow. References: Allen, Frederick Lewis, Only Yesterday, 1931; Jeansonne, Glenn, Transformation and Reaction: America, 1921-1945, 1994; Nash, Roderick, The Nervous Generation: American Thought, 1917-1930, 1970; Shaw, Arnold, The Jazz Age: Popular Music in the 1920s, 1987; Skidmore, Max J., Legacy to the World: A Study of America's Political Ideas, 1998.