Come to My Garden: 2002 Flower Communion

advertisement

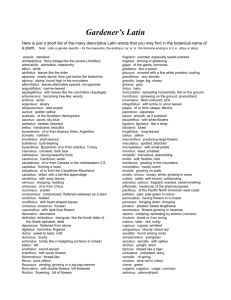

Come to My Garden: 2002 Flower Communion by Elizabeth Ihle June 30, 2002 Morning has broken like the first morning; blackbird has spoken like the first bird. Come with me this morning to a summer's garden, a place where you can find a haven, and visit with me there. My garden is a rainbow of color produced by flowers, birds, and grass; yours may be of a more practical nature and its vegetables nourish you. Whichever it is, it offers us a respite from the world, nourishment for our souls, and an encyclopedia of musings about life. I suspect these reasons were responsible for Norbert Capek's choosing flowers for an act of communion for Unitarian-Universalists about eighty years ago. In celebrating this communion, we celebrate Capek's life and well as the lives of all of us today. So this morning, here's where I'm going: I'd like to remind us a bit about Capek's life, then talk about gardens and flowers, and finally share some lessons that gardens offer us. In the years immediately following the First World War, Norbert Capek, who had once been head of all the Baptist churches in Bohemia, discovered that he had begun to embrace theological and religion convictions which were simply too liberal for that religious community. In response, he founded the Unitarian movement in Czechoslovakia. Many of its members, like Capek, had grown up in other religious communities and found that their spiritual needs could not be met by the now seemingly empty ceremonies and the hymns that were part of the churches of their childhood. Dr. Capek responded by writing hymns of his own and devising new ceremonies. One of the most successful of these new ceremonies was the flower communion service, in which each person in the congregation brought a flower to church and placed it in a vase. This simple ceremony began to spread among American Unitarian Universalists about the time that Dr. Capek was executed by the Nazis in a cruel medical experiment at the infamous death camp at Dachau. This morning, to celebrate this warm and beautiful season, to remember Dr. Capek and all those who, like him, have lived and died for their faith, we join in a version of the flower communion service. Now for a little bit about flowers. Botanist Michael Pollan (don't you think Pollan is a terrific name for a botanist) in his book The Botany of Desire: A Plant's-Eye View of the World, reminds us that all living things share the impulse to create copies of themselves and that plants have developed a number of evolutionary strategies to do just that. Plants have actually been evolving much, much longer than we human beings have and are nature's alchemists, expert at transforming water, soil, and sunlight into an array of precious substances, many of them beyond the ability of human beings to conceive, much less manufacture. While we were mailing down consciousness and learning to walk on two feet, they were, by the same process of natural selection, inventing photosynthesis (the astonishing trick of converting sunlight into food) and perfecting organic chemistry. Pollan says that one of several survival strategies for plants is to produce flowers so lovely that people will want to grow them. Although we often forget, all plants have flowers. To some folks, beauty is the breath-catching sight of a glossy bell pepper hanging like a Christmas ornament or a watermelon nested in a tangle of vines. So for some of us, the flowers we welcome into our gardens are precisely the ones that have a point, that tell of a fruit yet to come: the pretty white-and-yellow button of a strawberry blossom that soon would swell and redden, the ungainly yellow trumpet that heralds the zucchini's coming. Teleological flowers, we might call them. Most people enjoy the plants whose flowers stimulate our sense of beauty; in fact, psychiatrists have regarded a patient's indifference to flowers as a symptom of clinical depression. It seems that by the time the singular beauty of a flower in bloom can no longer pierce the veil of black or obsession thoughts in a person's mind, that mind's connection to the sensual world is dangerously frayed. But most of us, as far back as people have been leaving records, have enjoyed flowers. Among the treasures the Egyptians made sure the dead had with them on their journey into eternity were the blossoms of flowers, several of which have been found in the pyramids, miraculously preserved. The equation of flowers and beauty was apparently made by all the great civilizations of antiquity, though some-notably the Jews and early Christians-set themselves against the celebration and use of flowers. But it wasn't out of blindness to their beauty Jews and Christians discouraged flowers; to the contrary, devotion to flowers posed a challenge to monotheism; the flower was a bright ember of pagan nature worship that needed to be smothered. Incredibly, there were no flowers in Eden-or , more likely, the flowers were weeded out of Eden when Genesis was written down. The love of flowers is almost, but not quite, universal. The "not quite" refers to Africa, where English anthropologist Jack Goody writes in The Culture of Flowers, that flowers play almost no part in religious observance or everyday social ritual. (The exceptions are those parts of Africa that came into early contact with other civilization-the Islamic north, for example.) Africans seldom grow domesticated flowers, and flower imagery seldom shows up in African art or religion. Possibly the explanation for this is that people can't afford to pay attention to flowers until they have enough to eat; a well-developed culture of flowers is a luxury that most of Africa historically has not been able to support. The other explanation is that the ecology of Africa doesn't offer a lot of flowers, or at least not a lot of showy ones. Maybe the love of flowers is a predilection all people share, but it's one that cannot itself flower until conditions are ripe-until there are lots of flowers around and enough leisure to stop and smell them. There are flowers, and then there are flowers: flowers, I mean, around which whole cultures have spring up, flowers with an empire's worth of history behind them, flowers whose form and color and scent, whose very genes carry reflections of people's ideas and desires through time like great books. The rose, obviously, is one such flower; the peony, especially in the East, is another. The orchid certainly qualifies. And then there is the tulip. Arguably there are a couple more (perhaps the lily?), but these few have long been our canonical flowers, the Shakespeares, Miltons, and Tolstoys, of the plant word, voluminous and variable, the select company of flowers that have survived the changes in fashion to make themselves sovereign and unignorable. So what sets these flowers apart from the run of charming daisies and pinks and carnations, not to mention the legions of pretty wildflowers? Perhaps more than anything else, it is their great variety. Some perfectly good flowers simply are what they are, singular and, if not completely fixed in their identity, capable of ringing only a few simple changes on it: hue, say, or petal count. Prod it all you want, select and cross and reengineer it, but there's only so much a coneflower or a lotus is going to do. Fashion is apt to pick up such a flower for a time and then drop it since it won't let itself be remade in some new image once its first one is passé; think of the pink or gillyflower in Shakespeare's day or the hyacinth in Queen Victoria's. So enough information about flowers and gardens. What lessons for our lives can we draw from them? Lesson one: there is a season for everything. As Ecclesiastes 3 tells us, "For everything there is a season, and a time for every matter under heaven, including a time to sow and a time to reap. Our experience of flowers is deeply drenched in our sense of time. Maybe there's a good reason we find their fleetingness so piercing, can scarcely look at a flower in bloom without thinking ahead, whether in hope or regret. We might share with certain insects a tropism inclining us toward flowers, but presumably insects can look at a blossom without entertaining thought of the past and future-complicated human thoughts that may once have been anything but idle. Flowers have always had important things to teach us about time. We are now in high summer, the first of July, and our gardens are so crowded with flowers, are so busy and various, that they feel more like 33 East than a quiet corner of the countryside. The bees, butterflies, moths, and other insects are the minor actors, while the flowers are the chief players in the garden's drama, each of them taking a brief turn on the summer stage. The tulips, jonquils, and snowballs left long ago, the peonies are now gone, the campanula is waning, the coneflowers are just coming into their own, and the daylilies are at their peak. The flowers teach us the lesson that variety enriches and now is the season to celebrate the richness of life; the title of Barbara Kingsolver's wonderful novel Prodigal Summer really says it all. Let us simply enjoy the richness, bounty, and diversity of life and the gardens around us. Lesson Two: Gardens Are Work Planting in the springtime is a happy and hopeful activity, just as is beginning a new job or hobby. Maintaining a garden, just like maintaining our lives, is work. To a large degree, what you put into it is what you get out of it. A wise career counselor once told me that the best job to have in life is one where you get paid for having fun, and there's a lot of truth in that. If we can take joy in our work, then work becomes fun. Although I find weeding somewhat tedious, I can still take a lot of satisfaction in the results. Let me add an aside here about weeds. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Thistles, dandelions, Bittersweet Nightshade are all beautiful, but we've been acculturated not to tolerate them. Sometimes that happens with our views of people too. As the Rodgers and Hammerstein song from South Pacific notes, "You've got to be taught, before you are six or seven or eight, to hate all the people your family hates, you've got to be carefully taught." Sometimes we need to rethink what our weeds really are. Lesson three: Life isn't fair. I'm a klutz, and in my garden accidents happen. Despite my best intentions, I have stepped on and broken irreparably more than one begonia that the week before I had lovingly set into the ground. The same thing is true in life; accidents happen. Despite our very best intentions, our actions sometimes go astray and misfire. Now if that weren't enough, we also contend with Mother Nature. Have you heard the rule around here that we can plant your annuals after Mother's Day and rest assured they won't be killed by frost? Well, this year it didn't work; we had a frost on May 20th, and a lot of gardeners were scrambling to find replacements for the annuals they lost. The lesson in this is that even when we play by the rules, the rules sometimes change. That, folks, helps keep us humble. As I have worked in my garden, especially in the spring as I trim my butterfly bushes almost to the ground to stimulate new growth and beautiful July and August flowers and in mid summer I trim the chrysanthemums to produce better fall flowers, another of the garden's lessons pops up at me: pruning can be a good thing. In the garden, pruning, while brutal at first, produces growth. Sometimes our lives get pruned too-by personal or family illness, job loss, or the breakup of a marriage or close friendship. These are accidents we wish would never happen, and they are not easy to take, but often this kind of life pruning leads to a new life, a new wisdom, that would have never occurred without such accidents. Norbert Capek's death, while truly tragic, has given UUs worldwide an opportunity to celebrate flowers and to cherish the beautiful differences among us. Lesson three: Fertilize. A far happier and less stressful way to stimulate new growth is with fertilizer. We all know that gardens grow more abundantly with some extra nourishment, and so many of us regularly get out the Miracle Gro, the Plant Tone, the Rose Tone, or what have you to encourage our flowers and vegetables to be more beautiful and productive. The life equivalent is, of course, kind deeds and words, for they make our relationships richer and more abundant. "May the kindness which we learn light our lives 'til we return" has a lot of truth in it. We grow into better people when we fertilize the lives around us with supportive actions and words, and in turn we ourselves benefit from the kindnesses of others. Victorian essayist, art critic, and poet John Ruskin noted that "Kind hearts are the garden/Kind thoughts the roots/Kind words are the blossoms/Kind deeds the fruit." So we have four large lessons from our gardens: the seasons give us time for everything and we need to enjoy each one and the diversity that each brings, to a large degree we get from our gardens and our lives what we put into them, accidents happen but they can sometimes lead to even more growth, and finally we need to fertilize our gardens and our friendships. In a spirit of celebrating the seasons and diversity, realizing that work is part of the fabric of gardens and of life, understanding bad things sometimes happen to us all, and in resolving to fertilize our gardens and our friendships, let us sing our closing hymn #324 "Seed Not Afar for Beauty" during while we are all invited come to the front and select a flower from our communion vase to take home and cherish. Afterwards we will have time for a bit of dialogue before closing with our community sending forth and a benediction.