Interfaces, Frequency, and the Primary Linguistic Data Problem

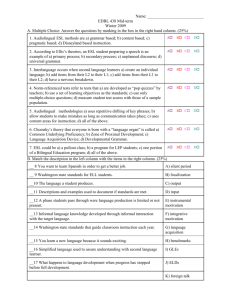

advertisement

[For Proceedings of Conference on Frequency in Wuppertal, 2008]

Interfaces, Frequency, and the Primary Linguistic Data Problem

Abstract:

Interfaces are definted biological relatioins, like the link between

heart and lung, while interactions describe non-designed but inevitable

biological consequences of being a mechanism with a single source of

energy. A careful look at the representations needed show that each

mental module has a separate form of representation. And therefore

interfaces require careful matching. Merge and labeling describes

a hierarchy in language but perhaps not other mental hierarchies. It is distinct from

Concatenation, which may be a broader mental capacity; Language calls for recursive

Merge and Label hierarchies.

We argue that “frequency” is not a meaningful concept in psychology

without a representation whose frequency is being tabulated. Therefore every model of

change must work with representations. However it is possible for representations that

are not perfectly captured by grammar to be identified. For instance, the notion of

leftward focal stress can apply at the word, phrase, or morphological level at first before

being liniked to sepate modules in the mature grammar. Lebeaux’s notion of AdjoinAlpha as an acquisition primitive is thereby supported. In sum, it is possible that

frequency-linked representations, still connected to an innate UG, play a role in

acquisition. We conclude with an analysis of gradual –ed acquisition that re-introduces a

role for LAD.

1.0 Introducton

The classic contrast between Empiricism and Rationalism falls under a new light

when we try to build realistic, mechanical interfaces that will assist in language

acquisition. The notion of an interface automatically entails the assumption that other

mental modules---with other mental purposes---are systematically engaged not only in

our model of adult grammar, but possibly with a special role in the acquisition process.

Does grammar interact or interface with a General Learning Capacity, familiar

from behaviorist and connectionist approaches in the empiricist tradition?

A prior question is whether there are any General Learning Capacities? Daily life

gives us the impression that we can develop knowledge schemes whose heterogeneity

would suggest that such General Abilities exist. Nonetheless one of the lessons of using

modes of formal representation for grammatical theory is that abstractions have strong

biases that are visible only when abstractly formulated. A second possibility is that the

identical ability is independently represented in the brain. We illustrate each of them.

1.1 Interfaces and Interactions

First we need to articulate an elementary contrast. The suggestion (Chomsky

(2005), (2008)) of an interface with a “conceptual-intentional system”, for instance,

means that our methods for representing actions of all kinds are linked--- in highly

particular ways----to our linguistic system. For instance, whatever notion of Agency

exists in planning action gets linked to the affix –er in language in a sentence like John is

the organizer.

By contrast, the notion of interface (see Roeper 2009) must be kept distinct from

the broader notion of an interaction. All bodily activities interact----solemn verbal news

might cause a heartattack, but that does not mean that there is specific architecture

linking the heartpump and the representation of a recent Past Event in language.

The distinction can be captured with an image: the sharpest example of an

interface is like a key and a keyhole. One is designed to fit the other. The empty space

has the “concept” of a key in it, but it is made of air.

An interaction, however, occurs when any two objects share an energy source, say

if a runner slows down if he wants to converse. Each activity (run, talk) must draw from

a common source of energy but they are not architecturally linked in an interface.

1.2 A Formal Approach: Concatenation versus Merge

Hornstein (2009) argues that Concatenation---the capacity to combine indefinite

numbers of obects: A, B => {AB} which then can be combined with C => {ABC} is a

kind of pre-linguistic capacity, but UG uniquely defines Assymmetric Merge.

We take Concatenation to guarantee association but not ordering, therefore it is a

form of Set Formation.

Computer scientists often include ordering, but there is logical possibility of

association without ordering. Therefore: AB = BA. Thus the linguistic module

interfaces with a Concatenation capacity which might be used to divide chairs in a room

as well as organize words in grammar. Concatenation, in this sense, captures a kind of

iterative recursion which which is reflected in an instance of conjunction, applicable to

any linguistic category:

(1)

Noun: John, Bill, and Peter left

Preposition: Bill jumped over, under, around, and through a hedge.

Notably the interpretation does not change if the order of elements changes (Bill,

Peter, John left). Recursively embedded possessives involve order effects (my father’s

friend’s car =/= my friend’s father’s car), which characterizes the central grammatical

notions of recursion.

Grammatical hierarchies are a particular choice from numerous possible

hierarchy types because they involve Labels, Assymmetric Merge, and binary structures

which allows the Label to express a directional bias:

(2)

A

/ \

B A

B

=/= / \

B A

N

/ \

Adj Noun

|

|

blue ocean

A

/

\

N

Adj

|

|

ocean blue

Thus the labels allow us to say that blue ocean is a kind of Noun and ocean blue is

a kind of Adjective.

The notion of Assymmetric Merge here has a plausible claim to the idea that it

reflects a UG specified instance of innate predisposition. In the grammar it is the

interface with Labelling which makes it particular to grammar, and which by hypothesis

invokes the innate dimensions of Universal Grammar.

If it operates immediately as a mechanism, then it provides further support to the

notion that it is innately specified. Roeper (1981) argued that all mental operations might

be decomposeable into units found elsewhere in the mind. If so, it is the claim that they

are mechanically connected which is the locus of innate structure.

It is possible that the artist who uses a form of Concatenation to group objects or

colors is allowing an interface between a Concatenation ability and a 3-dimensional

model that imposes constraints other than labeling (or in addition to Labeling).

It is also possible, in fact likely, that the Concatenation capacities linked to 3dimensional abilities are biologically independent even though conceptually identical.

It would be hard to imagine (though not impossible) that an injury to the

Concatenation Module which would suddenly affect both language and visual

organization in the same way.

1.2.1 Multi-dominance

There are other possibilities that show a more complex hypothesis space, for

instance, Multi-dominance models, which are gaining a footing in linguistics and which

may be pertinent to visual planning as well. These are trees of the following form

which, again, might be useful visuallly:

(3)

A

B

/ \

/ \

F

C

G

/

\

D

E

Here one node (C ) has two higher nodes. Multi-dominance seem intuitively

appealing for structures like: John saw Bill swim where Bill is the object of see and the

subject of swim (S. Cable pc).

It is an empirical question, with acquisition consequences, whether such

representations that increase the power of grammars, are necessary.

It is an interesting fact that among children’s first 3-word sentences we find:

(4) “help me dress”

which suggests that if this is the correct analysis of the adult grammar, then it is

immediately available to the child because me is both object of help and subject of dress.

Even if there are common connections between the formal structures behind

vision and language there is, by hypothesis, a specific genetic bundling that allows these

interfaces to be built so that they can participate in very rapid mechanisms.

Thus although we are capable of making a generalization over the abstract notion

Concatenation, it is not clear that it refers to any particular, independent biological entity,

which the brain draws upon. Another example may help. Both eyes and ears utilize

stereoscopy to develop a single representation from two sources. Yet we all suppose that

the property of stereoscopy is separately represented—and innate-- in these domiains (we

don’t lose out auditory ability if we are blind or vice versa--see Roeper (2007) for more

discussion). Concatenation like stereoscopy may not describe an ability that is separately

represented in the biology of the mind for modules like language and vision.

2.0 Frequency

Now let us introduce a topic that seems to have perennial interest: frequency. It is

evident in everyday life and in many psycholinguistic experiments that, at some level,

frequency seems to dictate acquisition order and processing preferences. These are broad

generalizations which need to be articulated in the kind of abstract terms we have

introduced.

First there is a fundamental logical observation that seems to go often

unrecognized. There is no possible mental ability that can capture frequency without a

form of representation for the object counted (Roeper 2008).

If I hear X six times, it is impossible for me to know that unless I can represent X

in some non-auditory mental form such that I knew that I heard it before when I hear it

again. If it disappeared entirely, I could not know I heard it. If I know I heard it, then I

must have some mental representation that allows me to assert that it is identical to that

representation. The sound representation, of course, is a very complex object never

perfectly reproduced and therefore the form must be abstracted.

What is the abstraction? Would it be the same as a cat’s, dog’s, or monkey’s? To

take another example, if I show you red, green, and yellow apples, and ask how many

apples you see, you must be able to have an apple representation which is not

automatically red, green, or yellow but essentially abstract and without a fixed color in

order to count them. The same holds for sounds: they vary in form depending upon

volume, duration and much phonotactic variability which must be abstracted away from

in order to create a representation to compare to incoming sounds.

While sensitivity to frequency and statistical generalization might seem to be a

good candidate for an independent mental module, it might also be built into various

mental abilities in very precise ways. If so, then we have re-established the need for

claims about prior linguistic assumptions. Are we tabulating frequency in all directions

at once? If an interface between two systems is fixed, then it can participate in a

frequency representation. If the interface is arbitrary, then it is obviously beyond

computation, as an example will readily reveal.

Suppose the notion of agency involved cross-modular representations, jointly

computed. Then we might expect that the mind has an implicit number representing the

frequency of agency that is the combination of how often you see someone act

deliberately (eat a banana) and how often you hear the –er on words like winner and

singer. So we might, though it is doubtful, have a representation of Agent every time

someone does something manifestly deliberate. While each form of agency might be

tabulated for frequency, it is implausible that we compute the combination.

However if Agency-frequency were specifically tabulated with rerefence to

morphology, we might know how often –er is linked to AGENT, how often to

INSTRUMENT, and how often to THEME. This tabulation could, and perhaps does,

dictate the fact that Agency –er is productive, and the other two are rather exceptional,

particularly the THEME case. While a broiler may be a chicken, a cooker is not the

object cooked, both forms allow an Agent reading (even if we have heard cooker only as

an instrument.) Thus one formal/meaning interface –er/AGENT is being counted. If

frequency is measured, it seems very likely that it will follow fixed interfaces, which

means in effect that it is defined already within the system it is tabulating. Therefore the

liklihood that there is a truly independent statistics-analyzer seems very small.

3.0 Acquisition and the Initial State

Now let us turn to the acquisition question. What generalizations define the

“initial state” of our language acquisition capacity? One assumption is that it is a Default

Grammar which undergoes modification upon the presentation of new input data.

However there are other possibilities which deserve attention. In the Aspects (1965)

model Chomsky discusses the question of how we represent the Primary Linguistic Data

(PLD). He suggests that some forms of distributional analysis modeled on structural

grammars could be present at the outset which, moreover, are contained in a Language

Acquisition Device (LAD) that is present at birth but declines with age. It is certainly

notable that children learn words at an astonishing rate: 14.000 by the age of 6yrs which

is roughly one an hour. As adults we are often called upon to learn words with a single

exposure---as when one tries to retain the name of someone just introduced---but we do

not seem to learn words quite as fast as children.

One reason that Chomsky introduced the possibility of LAD is that he assumed

the presence of Phrase-structure Rules of the form:

(5) Sentence => NP VP

This representation is, obviously, far from the child’s initial experience of streams

of sounds. Therefore the child must have segmentation and data-sorting capacities for

hierarchical abstraction and specific nodes in order to get the representation to the point

where it could submit to any analysis at this level. Under Minimalism, however, notions

like Merge and Label appear to be much closer to the primary data. This is an important

and under-appreciated point. The idea that greater abstraction could be closer to

experience seems counter-intuitive. Why could it be true? Because abstract Merge

allows analysis of very early structures in asymmetric terms before higher phrasal

categories (like NP and VP) can be formed and recognized. In fact, Chomsky has argued

that initial Merge may be lexically based, but still asymmetric, if the word itself is

projected:

(6)

the

/

\

the book

In fact this notion generates an hypothesis about early stages which is subject to

proof.

(7)

Hypothesis 1: children begin with Concatenation

Hypothesis 2: children begin with Asymmetric Merge

If Concatenation were true, then we would expect children to reliably associate two

words, but be indifferent as to their order. In fact, however, it has been argued since the

first work on two-word utterances that children impose word-order from the outset, even

with expressive terms that have no grammatical category:

(8)

hi Mom/*Mom hi

well, yes/*yes well

it big/*big it

In fact every grammar of the two-word stage has imposed order, although if

concatenation were an independent ability, and if it were independently open to a

frequency calculation, then it would certainly be true that children should have a stage

where they accepted unordered representations and used them.

Therefore it appears, from the outset, that the innate system finds an inherently

more complex structure, Merge and Label assymmetrically, in fact easier, just as we find

it easier to see in 3 dimensions than in 2 dimensions although one could argue that a 2dimensional structure is a logical subset of 3-dimensions and “simpler”.

3.1 Transition Probabilities

The logic of order sensitivity is captured in non-grammatical terms via the notion

of Transition Probability. That is, a child is sensitive to what typically follows a sound or

a word. However one could easily build a machine that was sensitive only to

Concatenation or Set-formation with unordered sets. Thus the machine would note:

(9)

cats

cast

and see that both words contained {s,t} and therefore indicate a frequency sensitivity to

the combination without respect to order. Thus even those models which claim that they

have a bias that is not “linguistic” in character implicitly have a very suitable bias in the

notion of “transition probability” which from a mathematical point of view appears to be

more complex than an unordered set.

Of course, this is really an empirical question: do children recognize unordered sets

as easily or more easily than sequences with a transition probability? The experiment

would be: is there any environment, for instance vision, where an unordered array is more

easily learned than an ordered one (where the whole array is guaranteed not to be seen as

a unit)? This is an empirical question for which there may already be evidence in the

psychological literature.

4.0 Pre-linguistic Representations

Where might we look for representations that do not fall within those directly projected

by Minimalism. We might expect words to be simply represented phonologically on a

frequency basis and learned in that order. However, we need to carry out the

segmentation that identifies words and distinguishes them from bound morphemes.

Without such an assumption one would assume that an extremely frequent word

like the would be among the first a child uses, since they are very frequent, but they are

late acquisitions for English-speaking children. On the other hand, in languages like

German den (the) arises much earlier. Why? In fact, the article functions as a pronoun

and can appear independently, and we know that in English, demonstrative pronouns like

that arise very early. By independently we mean that a discourse might allow them to

appear alone:

10)

Speaker 1: which do you want? [welchen möchtest Du]

Speaker 2: den! (*the)

Now we have actually imposed an important criterion: independent appearance. If the

system were not built to recognize the distinction between bound and unbound we might

expect a child to acquire a morpheme like ing with the meaning of activity. How could

that work?

We know that children hear ing often—and in diverse contexts. But one

contextually salient domain is ongoing activity which the child might recognize as such

and link the verb to activity. It is likely that other uses linked to intention ( “going to”) or

nominalization (the reading) will be acquired in a different sequence. Suppose a child

walked into a room buzzing with other children playing and yelled “–ing”. This would

be very plausible given the pragmatic salience of human bustle and phonological clarity.

And yet no one reports such a result and it seems intuitively alien. It is intuitively alien

because our intuition of what a natural child utterance is, itself, dependent upon innate

structural features, such as the principle independent appearance as a criterion for words.

The topic is one of interest. Children do allow backformations which infer words,

such as the child who said “I have a hammer because I like to ham”. The prediction is

then that purely morphological elements, unlike stems, are not mis-identified as words.

Could there be, or should there be, representations which fail to be possible UG

representations that are nevertheless useful to children? Our image of acquisition is much

like a quadratic equation where several modules posit structures which serve as sources

of confirmation for each other. Inversion, question intonation, and situations where a

question is natural can all coincide to tell us that these ingredients of question-formation

are correctly analyzed. Therefore the correct grammatical alignment may involve a shift

in representation at multiple levels. While it is attractive and perhaps probable that all

representational powers are derived from principles of UG, they might look a bit

different, or tolerate unusual variants in the acquisition process. It is precisely here that

aspects of frequency might play a role.

4.1 Focus

Intonation and focus intonation in particular fail to have a perspicuous mapping

onto individual words or morphemes in many instances---it seems to hover over larger

units. In addition it is interpretively relevant for units as large as sentences and as small

as morphemes. That is, exclamatory stress emphasizes an entire sentence while Focus

can fix on just a morpheme:

(11) a)You played baseball today!

You RE-read the book, good for you!

How would the child, the acquisition mechanism, attack the Focus intonation system?

Will it begin with the right phrasal divisions?

The challenge for many acquisition problems is to envision plausible logical

stages. Suppose children seek broader representations first. They could generate a

representation that allowed this common perception: Focus occurs leftmost for the

sentences in (11b):

(11) b) WHAT do you want

EGGS I like

MEAT-eating is good

NO run/*run NO (except if there is a pause)

Notice that leftmost like the linear notion of V2, does not fall out of most theories,

although it seems akin to principles of linearization. What is leftmost operating upon

exactly? It seems here that one might invoke the notion of utterance as an independent

intonational object, but this could cut out a lot of available information such as:

(12)

Aha, MEAT-eating is bad

John thinks MEAT-eating is bad

Bill thought that MY HOUSE he might be willing to buy.

This is plausibly a good first move if one needs to grasp an intricate concept in smaller

steps. This is now an empirical question: would a child be able to identify leftmost stress

in an utterance, and therefore be unable to identify the stresses in (12), but see those

in (11b) as a first generalization? The naturalness of such a proposal increases when we

consider the notion of leftmost to be the prototype for the concept of EDGE in current

minimalism.

One reason that it is perfectly possible that an odd, and hard to notice,

step occurs in the acquisition path of every child is that it might also be quite short-lived.

Just like half a dozen crucial adjustments occur in a half hour span when a child learns to

walk or balance on a bike, a microscopic, but very significant series of steps could be the

substructure of many acquisition stages which our current data-gathering practices do not

identify.

In (12) the notions of leftmost could be extended to capture the facts, but it requires

recognition of other phrases, like Nounphrase and Clause, whereupon one might use

another linguistic notion PHASE EDGE to capture the concept. It would have to be

extended to include complex words as PHASES to capture focal stress inside compounds.

But now such steps would presuppose that one already identified a host of languagespecific properties, like a left-peripheral TOPIC position in an embedded clause that

qualifies to be a PHASE.

Now we will encounter classic learnability problems where each decision depends

upon the other. It is here that the order of decisions and a representational basis for

acquisition must be articulated. Nevertheless one could imagine frequency definitions

that would be connected to grammar-independent notions that defined first steps. This

would be the kind of analysis of Primary Linguistic Data that could be accomplished

through a language-specific acquisition device, or could depend upon capacities defined

over domains much broader than language.

4.2 Focus and Contrast

What epistemological sequence can be imposed on a learning sequence that is defineable

immediately in terms of properties of Primary Linguistic Data. We were trying to find

pre-existing diagnostics that did not depend upon prior language-specific decisions. We

chose leftmost as a possible concept, but then had to ask what structure could a child

presume on which to define leftmost.

This is a hard problem to which we do not have the answer. Therefore let us make

an assumption that seems intuitively plausible. The child has a broad-based linear notion

of leftmost: Focus seems to be at the beginning or toward the left in a sentence for a

sufficiently high proportion of sentences for a system to “take notice”. They must then

have an under-defined notion of utterance with enough internal structure to locate a

Focus element.

In addition, the child would want to hear a fairly frequent input sample to arrive at

this conclusion, including examples like those above. Thus the child might have a rule:

(13)

Assign Focus intonation to the left

when some notion of Contrast is intended.

In other words, frequency requires a minimal representation of some kind--perhaps partially non- or pre-grammatical—which is then subject to grammatical

analysis. This representation, we argue, is then abandoned step-by-step as the

particularities of each structure are learned. This differentiates comprehension from

production. Focus will only appear in production, unlike comprehension, when a

specific and acceptable grammatical form can be generated by the speaker.

Comprehension can allow a combination of a vague representation and essentially a

contextual guess.

A child might be able to guess, with half a grammatical analysis, that a passive is

meant by:

(14)

the HAMBURGERS were cooked by Dad

if they could recognize a focal element initially, hamburgers, and a connection to the

thematic structure of the verb cooked without yet being able to insert was, by, or

participle –ed.

Now let us illustrate the claim with a more precise example. Suppose a child hears

either of the phrases:

(15)

Johnny has a big DOGhouse ( = not cat house)

Johnny has a BIG doghouse ( = not small doghouse)

However let us assume, plausibly, that the child has not yet fixed where adjective phrases

occur (to the left or right), nor their recursive character (big, strange house), nor exactly

how compound words are built (BLACKboard). The child could implicitly think:

16) There is leftward contrast in this phrase, but I am not sure where.

Then the child might look and see if the context allows a contrast between big and small

doghouses or between doghouses and cathouses. At this point, the child could probably

make a good guess about what is being contrasted, without actually having an adult

representation of what is involved. The prediction would be that the child would not yet

produce contrastive stress on either the adjective or part of the compound noun, but could

often seem to understand it.

4.3 PLD and Adjunction

Can we say more about such a represenation? Suppose the child, unsure of what the

possible structures are, essentially adjoins the phrase. but then cannot locate Focus which,

in the grammar seeks a recognizeable node label, which can be obscure even for lexical

categories.

(17)

Focus => find recognizeable Node

Word+Noun = ambiguity

Pre-grammatical Adjunction representation = without node label:

(18)

=>

Focus /

\ =/=>

N

/

?

|

big

\

house [+N]

Here we argue that the child will shift the focus to the higher node, NP, which has a label

because they are unsure of the lower one and seek a contrast element anywhere below the

higher NP. There is evidence that children can recognize contrastive Focus without being

able to localize it on lower nodes (see Hubert (2009).

Thus children will answer a question like:

(19)

John has a BIG house and not……a car

while adults will say: ….a small one.

The child has allowed the actual focus on big to migrate upward to the node

Noun. The topic certainly deserves careful study (See Hubert (2009) for very pertinent

evidence on children’s understanding of recursive adjectives).

Lebeaux (2000) has argued that children begin with a rough notion of Adjoinalpha, which is obviously a linguistic operation. However, if the adjunction operates with

a mystery Node label, then it is “pre-grammatical” in the sense that it does not meet the

requirement that all Nodes have identifiable labels.1 We can argue for Pre-linguistic

representations for all of these structures which involve Adjunction with Labels that are

not yet grammatically fixed:

(20) intonation = (Left Focus +X)

affixation = (X + af)

complementation = [verb + X]

adjuncts = (by X)

([Adjoin-alpha] Lebeaux (2000)

These domains may be where small amounts of partially pre-grammatical structures are

possible. The prediction is precisely that it will affect comprehension and production

differently because adjoin-alpha is essentially a default parsing bias that even for the

child fails to be an acceptable grammatical representation although it is sufficient to make

semantic inferences upon.

Our broad hypothesis is:

(21) Frequency-based representations are dropped with full grammatical analysis.

This is a strong hypothesis that is not in keeping with those who attempt to utilize

frequency models as a substitute for grammatical ones. Let us now construct a more

precise scenario. It is actually an odd thing that production is used in arguments about the

role of frequency. It is certainly the frequency of input which makes a difference (see

Yang (2002)) for demonstrations of its relevance) in parametric choices. At the point of

production, there will be evident variation in the use of various constructions. It does not

follow that increases in frequency of usage are a result of a kind of habit-formation. It is

a less complex system, without a frequency counter, to argue that discrete changes in the

grammar, usually meaning related, will cause additions to the frequency of, for instance,

a morphological form. Thus if we add to the meaning observable ongoing action (they are

dancing) for –ing another meaning: intended action (I am going to the movies

tomorrow), then the frequency would naturally increase. Each form then may appear to

vary by frequency but small grammatical changes linked to meaning are at the root of the

shift.

1

In Roeper (2006) I argued that Compositionality was systematically a second order phenomenon.

That is, children adjoin at first without a label, but when adjunction becomes recursive, then it must have a

label.

4.4 the Past Tense Controversy

Let us provide another example of how stepwise enrichment interacts with

frequency. The most famous claim about the role of frequency lies in the apparent

gradual appearance of Past Tense –ed (Rumelhart and McClellan (1986)):

(22) X + ed => tabulate frequency

(23) Stepwise differentiation:

past tense [John walked]

transitive/intransitive

actional/non-actional [John was admired]

passive [the house was being painted]

implicit argument present

participle [the house was painted]

result reading

pronominal adjective [the painted house]

non-verbal adjective [three-cornered]

Suppose the child begins with the observation that –ed occurs at the end of some words:

Word+ed. We would predict no usage at this point. Suppose he then advances to: V +

ed.

From this point onward, it is unlikely that the –ed will be used without some

semantic features [past tense, perfectivity, result]. In addition, the label V may represent

only part of a Feature Bundle that UG says is necessary: designation of transitive,

intransitive, actional, and perhaps others. If the child requires several of these features to

be present, then –ed will emerge in a dozen steps in production as each domain reaches

an adequate level of Feature representation. This will produce, without a refined

analysis, the impression of gradual acquisition when in fact a subtle stepwise acquisition

is present where, once acquired, frequency is relevant and contextual necessity is the only

criterion.

5.0 Conclusions

We have sought to explore how the PLD can be realistically represented in light of the

abstractions offered by Minimalism. We pointed out that these abstract notions of

hierarchy involving Merge and Label, may in fact offer simple modes of representation

over which pre-grammatical generalizations, minorly sensitive to frequency, could be

computed. We argued that when full grammatical representations appear, pregrammatical representations are simply abandoned. In this respect, our perspective

resurrects the notion of a Language Acquisition Device that is tightly connected to UG

but not identical to it.

We used Contrastive Focus as an exmple of an interface phenomenon whose

acquisition might involve a number of steps that a changing representation would

accommodate.

We reviewed a number of core concepts in linguistic theory in light of modern

evidence: the initial state, primary linguistic data, interfaces, and learnability arguments.

All of these arguments served, in our view, to etch in the core conceptions behind the

innate model of language acquisition while building precise connections to other modules

of mind.

Bibliography

Chomsky, N. 2005. Three factors in the language design. Linguistic Inquiry 36:1–22.

Chomsky, N. 2007. Approaching UG from below. In Interfaces + recursion =

language? Chomsky’s minimalism and the view from semantics, ed. U. Sauerland

and H.-M. Gärtner, 1–30. Mouton de Gruyter

Chomsky, N. (2008)” Evolution of Human Language” The Morris Symposium

MIT ms.

Chomsky, N. (1965) Aspects of the Theory of Syntax MIT Press

Hornstein, N. 2009. A Theory of Syntax: Minimal Operations and Universal Grammar

Hubert, A. (2009). Thesis on the Acquistion of Adjectives and Ellipsis

Potsdam University

Lebeaux, D. 2000. Language acquisition and the form of grammar. Amsterdam: John

Benjamins.

Roeper, T. (1981) "The Role of Universals in the Acquisition of Gerunds", in L.

Gleitman and E. Wanner (eds.), Language Acquisition: The State of the Art,

Cambridge University Press (l982), 267-287.)

Roeper, T. (2007) The Prism of Grammar: How Child Language Illuminates Humanism

MIT Press

Roeper, T. (2008) “What frequency can do and what it cannot” in

The Role of Input in Language Acquisition

eds. N. Gagarina and Insa Gülzow (2008) Mouton

Roeper, T. (2009) “Microscopic Minimalism” Proceedings of BUCLD 33

Cascadilla Press

Rumelhart, D.E. and J.L. McClellan (1986). "On Learning the Past Tense in

English". In McClellan and Rumelhart and the PDP Research Group (eds):

Parallel Distributed Processing: Explorations in the

Microstructure of Cognition. Volume 2: Psychological and Biological

Models. Bradford Books. Cambridge Mass.: MIT Press.

Yang, C. (2002) Knowledge and Learning in Natural Language MIT

Dissertation