Centrality of Central Asia

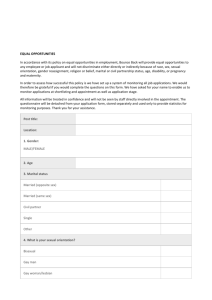

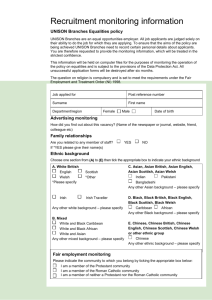

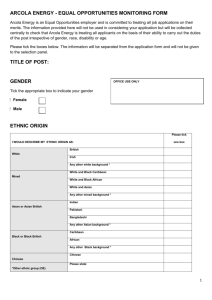

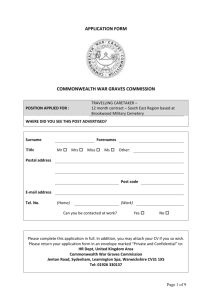

advertisement