Chicago Tribune

advertisement

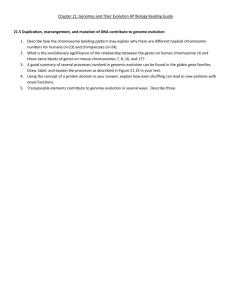

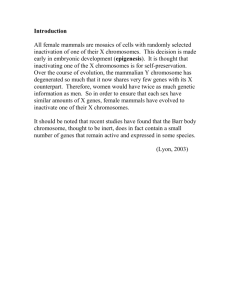

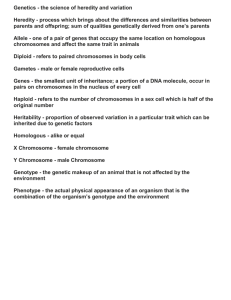

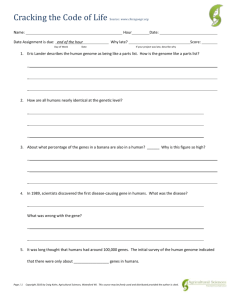

Chicago Tribune March 17, 2005 Thursday HEADLINE: 1,098 genes decoded, meet the amazing Ms. X; Mapping of the female chromosome, revealed Wednesday, will shed new light on disease and differences in the sexes BYLINE: By Peter Gorner, Tribune science reporter. BODY: An international team of researchers announced Wednesday that they have cataloged all the genes on the female X chromosome, a technical feat expected to enable fresh insights into women's health and add a genetic component to the debate over differences between the sexes. Described by the head of the Human Genome Project as "a monumental achievement for biology and medicine," the genetic map should help scientists better understand more than 300 X-linked diseases--such as hemophilia, Fragile X Syndrome and Duchenne muscular dystrophy--that mothers pass on to their sons. "From studying such genes, we can get remarkable insight into disease processes. But the importance of the sequence goes beyond individual genes," said Mark Ross, project leader at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Hinxton, England. "We have also gained a deep insight in the way evolution has shaped the chromosomes that determine our gender to give them unique properties." The accomplishment was reported in the British journal Nature. In humans and other mammals, sexual identity is governed by a pair of chromosomes known as X and Y. Every female has two X chromosomes, inherited from both parents, and all males have one X from their mothers and one Y that comes from their father and his line. With more than 1,000 genes and 160 million base pairs of DNA, the X looms like a giant next to the stunted Y chromosome that produces males. The Y chromosome--78 genes, 23 million DNA subunits--was completely sequenced in 2003. Because males carry only one X chromosome, they are particularly vulnerable to diseases carried by defective X genes. Women who carry such defective genes are usually protected by their backup copy of the X, but if their sons inherit that disease-causing X they are in trouble. More than 300 diseases already have been mapped to the X chromosome, and although it contains only 4 percent of all human genes, it accounts for almost 10 percent of inherited diseases caused by a single gene, which geneticists refer to as Mendelian disorders. The new genetic sequencing of the X so far has allowed the identification of 43 more genes responsible for conditions ranging from cleft palate and blindness to testicular cancer. New pathways of the immune system have been discovered and new cancer vaccines proposed. "By defining the 1,098 genes on the X, this analysis provides a rigorous foundation for exploring hundreds of human illnesses that map to this chromosome, from color blindness to mental retardation," said Dr. Francis S. Collins, director of the National Human Genome Research Institute. The sequencing was carried out by more than 250 researchers as part of the Human Genome Project. They worked at the Sanger Institute, Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics in Berlin, the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology in Jena, Germany, and Applied Biosystems Inc. in Foster City, Calif. In a companion paper in Nature, researchers at Duke and Penn State universities reported on the expression, or activity, of 471 genes on the X chromosomes belonging to 40 women. They were surprised to find a large amount of variation from woman to woman. "That variation is completely unique to women. The X chromosomes of males are all the same in that regard," said the lead author, Huntington Willard of Duke University in Durham, N.C. The finding, researchers said, suggests that individual women are likely to have different susceptibility to certain diseases. Researchers also compared the human X chromosome to the equivalent in other animals, opening a window into the evolution of sex chromosomes. Until mammals began to replace reptiles and rule the Earth about 300 million years ago, the X and Y were of equal size and able to swap genetic material with each other as needed. But over eons, the male-producing Y has been riddled by mutations and the trading of genes trailed off. The chromosome withered away in size, and its function became limited to establishing maleness, ordering the building of male sexual organs and conferring the ability to produce sperm. The X acquired more responsibilities and more genes while the Y "slowly but surely dropped off the face of the Earth," said Dr. Steven Scherer, director of mapping at the Baylor College of Medicine Human Genome Sequencing Center. "Although it contains a few important genes, it's almost like the appendix of the human genome." One of the enduring mysteries of the X involves a process called Xchromosome inactivation. More than 40 years ago it was discovered that, among females, most genes on one of their two copies of the X are silenced long before birth. The mechanism reduces the level of X-chromosome expression to the same level as that in a male, who has only one X. The system evolved to protect females against a double dose of genes, but science did not know precisely how it worked. Now the researchers have found that a particular type of repetitive genetic sequence consumes up to one-third of the entire X chromosome and may help muffle the genes. But Willard, along with Laura Carrel of Pennsylvania State University in University Park, also found that not all of the genes on the second X chromosome are inactive. About 75 percent are quiet all the time, but 15 percent escape inactivation and the remaining 10 percent are "leaky"--meaning they are inactive on some X chromosomes but not others. "Our study shows that the inactive X in women is not as silent as we thought, " Carrel said. "The effects of these genes from the inactive X chromosome could explain some of the differences between men and women that aren't attributable to sex hormones." The evolutionary argument for X inactivation had been that the process would equalize or normalize gene expression between males and females. "Everyone has bought into that for the last 40 years," Willard said. "But now we find as many as 200-300 genes on the X chromosome where females have not only more gene expression than males, but also extraordinarily variable gene expression, compared to what males have." Willard plans on studying whether the genes his team identified may explain why certain diseases occur in different frequencies in women and men. "Even aside from health, any of us over the age of 2 realizes there are plenty of differences between males and females that are characteristic of the two sexes," said Willard. "Some of those, no doubt, have a hormonal explanation; some may have a cultural explanation. We now have a reasonable clue that there may also be a genome explanation as well for genes that are expressed differently in males and females." There may even be two human genomes: female and male, Willard said. "We get terribly excited by the fact that humans and chimpanzees only differ by 1 1/2 percent genetically," he said. "Well, women and men differ by 1 percent. That's significant and worth studying." Although the studies published Wednesday are expected to galvanize X-chromosome research, it may take years for advances to be felt. Of the thousand genes identified, science has a good idea of what only 500 or so do. "When the stories of all the chromosomes are eventually published, I expect this chromosome to be the All-Star," Scherer said. GRAPHIC: GRAPHIC: FEMALE X CHROMOSOME 1,098 genes 160 million DNA base pairs Sequencing completed this year GRAPHIC: MALE Y CHROMOSOME 78 genes 23 million DNA base pairs Sequencing completed in 2003 GRAPHICS 2