Acute portal vein thrombosis: a concise review

advertisement

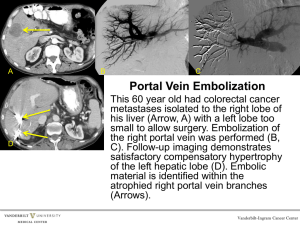

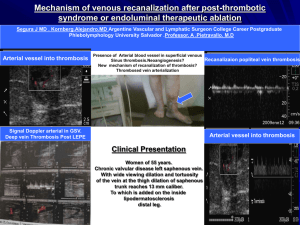

Acute portal vein thrombosis: a concise review. Until recently portal vein thrombosis was recognised late, usually with portal hypertension. Therefore clinical features of acute portal vein thrombosis are poorly defined in the literature. The proportion that progress to chronic portal vein thrombosis and the influences of the various treatments are not well known. Portal vein thrombosis is being recognised with increasing frequency with ultrasonography. This is a condition, which if not recognised early, leads to long-term sequelae. Hence, clinicians dealing with acute emergencies should be aware of the symptoms, signs and means of diagnosis. The surgical team may be involved in the early care of these patients as non specific abdominal symptoms are often the initial presentation. In this article, the existing literature on acute portal vein thrombosis is briefly reviewed. Portal vein thrombosis is a well-defined cause of portal vein obstruction. It was first described in 1868 1. Normally portal vein constitutes two-third of the total hepatic blood flow. Still occlusion of the portal vein by a thrombus often does not produce an acute manifestation. The reasons being a compensatory vasodilatation of the hepatic arterial system as also the rapid development of tortuous collateral veins bypassing the blocked portal vein 2-4 . These collateral veins eventually make up the cavernoma. Collateral veins develop within the walls or at the periphery of the structures adjacent to the obstructed portion of the portal vein: bile ducts, gall bladder, pancreas, gastric antrum, and duodenum. The collateral veins may alter the aspect of these structures at imaging and, occasionally, this will lead to erroneous diagnoses of bile duct or pancreatic tumour, pancreatitis or cholecystitis 5. As a result of arterial buffer response and development of the cavernoma, total hepatic blood flow is only minimally reduced. Portal pressure, however, is increased. The increase in portal pressure can be viewed as a compensatory mechanism allowing portal perfusion to be maintained through the collateral veins. Portal perfusion is maintained at the expense of portal hypertension and, eventually, gastrointestinal bleeding from varices. It is worth noting at this point that ruptured varices may belong to the portosystemic collateral circulation (in the oesophagus and the gastric fundus) or to the portal cavernoma (in the gastric antrum and the duodenum) 5. A cause for portal vein thrombosis can be identified in more than 85% of cases 6-7 . Portal vein thromboses occur only when several factors are combined 8. These factors comprise inherited or acquired prothrombotic disorders, other thrombophilic factors and local factors. Inherited prothrombotic disorders can be classified into two groups 2. The first one includes the long identified deficiencies in protein C, in protein S and in antithrombin. The prevalence of these anomalies in the general Caucasian population is low (<0.04%) and the associated relative risk of thrombosis in the heterozygous state is high (around 10). The second subgroup of inherited disorders includes conditions, which were recently identified like gene mutations in factor V Leiden (FVL) and factor II prothrombin. These are associated with lower relative risk of thrombosis being more prevalent in the general population (2%) 8-10 2-8 despite . The acquired thrombophilic disorders include malignancy, myeloproliferative disorders, oral contraceptive pills, pregnancy and postpartum, antiphospholipid syndrome and paroxysmal nocturnal haemogobinuria 11. Local factors that precipitate portal vein thrombosis can be classified into three categories. A first category refers to conditions characterised by local inflammation and infection. Neonatal thrombosis is well documented following omphalitis or umbilical vein cannulation complicated by septic phlebitis. Other infectious processes that may lead to portal vein thrombosis include portal pyaemia secondary to appendicitis, biliary tract infection, post abdominal surgical sepsis, amoebic colitis with hepatic abscess, acute necrotizing pancreatitis, diverticulitis and septicaemia 4. A second category of local factors refers to operations that, intentionally or not, involve injury to the portal venous system. As a rule, this type of operation does not precipitate portal vein thrombosis unless there is an associated prothrombotic state or portal hypertension 12 . A third category refers to cancer of abdominal organs. Hepatocellular carcinoma, often seen in association with cirrhosis, and pancreatic carcinoma comprise the majority of cases 1, 13 . Cancer can lead to thrombosis of the portal venous system through a combination of prothrombogenic changes, tumour invasion, and a compression or constriction effect from tumour mass 3, 14. To sum up, general thrombophilic factors should be investigated, even when a local factor for portal vein thrombosis is evident. Conversely, a local factor should be investigated even when a systemic thrombophilic factor is obvious 5. The discussion about the causative factors would not be complete without considering cirrhosis. Cirrhosis has been long considered a major cause of portal vein thrombosis in adults. The reported prevalence of portal vein thrombosis in cirrhotic patients varies widely from 0.6% to 26% 12, 15,16 . The pathogenesis of portal vein thrombosis in patients with cirrhosis is uncertain, although it has been suggested that decreased portal blood flow and the presence of periportal lymphangitis and fibrosis in these patients promote the formation of thrombus 17. The natural history of portal vein thrombosis is not known because in all reported cohorts of patients, some form of therapy was used for portal hypertension or thrombophilia. The rarity of the condition has not allowed controlled therapeutic trials to be conducted 18. The main complications of portal vein thrombosis are intestinal ischaemia and chronic portal hypertension. Intestinal ischaemic occurs when thrombosis extends to the mesenteric venules. When the ischaemic is prolonged for several days, intestinal infarction may follow. It is invariably fatal without prompt surgical intervention 4, 19 . Portal hypertension develops when there is no repermeation of the portal vein 18 . The proportion that progress to portal hypertension is not known. The overall prognosis for patients with nonacute portal vein thrombosis in the absence of cirrhosis or malignancy is good. The overall mortality from several studies has been less than 10% in this group 4, 20. The mortality in patients with acute portal vein thrombosis was approximately 50% in the past 13 . The mortality rate has gradually diminished over the years because of the advent of effective antibiotics, early surgical intervention and use of anticoagulants 21-23. The clinical course of patients with non-tumourous, non-cirrhotic portal vein thrombosis is complicated with recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding and thrombosis. A recent study found the incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding was 12.5 per 100 patient years. The size of oesophageal varices was the main independent predictive factor for bleeding. The incidence rate of thrombotic events was almost half of that of bleeding, but significantly the lethality of thrombosis was higher than that of gastrointestinal bleeding. The main independent predictive factor for recurrent thrombosis was an underlying documented prothrombotic condition 18. Four distinct clinical pictures can be observed with portal vein thrombosis 4 . First, there is the classic group of patients presenting with complications of portal hypertension. Haematemesis from rupture of varices is the most frequent presentation. The bleed is well tolerated with mortality of less than 5% 18, 20. Clinical examination reveals splenomegaly in most patients. Laboratory tests are mostly unremarkable. The second group consists of cirrhotic patients with portal vein thrombosis. Variceal haemorrhage is poorly tolerated in this group. Further abnormal liver function tests and intractable ascites are often present. The third group consists of patients with intra abdominal malignancy. These patients do not survive long enough to develop the sequelae of portal hypertension. Patients usually have ascites, anorexia and weight loss. The fourth group of patients present with acute portal vein thrombosis. Diagnosis needs a high index of suspicion and very often radiologist is usually the first physician to suggest the diagnosis on the basis of imaging findings. The patients usually have abdominal pain. Ascites may occur transiently immediately after the thrombotic event 6, 24, 26. Patients may have abdominal tenderness 6, 25, 26 . Other common complaints of patients with portal vein thrombosis include nausea, vomiting, anorexia, weight loss, diarrhoea and abdominal distension 4,6,26 . Further abnormal liver function tests are common with acute portal vein thrombosis, probably secondary to portal pyaemia 28. To sum up, diagnosis should be suspected in many different situations: abdominal pain, abdominal sepsis, and gastrointestinal bleeding due to portal hypertension or fortuitous finding of portal hypertension. The next step, once there is clinical suspicion of portal vein thrombosis is an appropriate radiologic approach to confirm the diagnosis. A duplex or colour Doppler-ultrasound is an appropriate first investigation. If the ultrasound study is non diagnostic, then MR is the procedure of choice. If MR is not available, dynamic contrast CT may be performed. If noninvasive tests are unsatisfactory, angiography should be performed 4. The next step following diagnosis should be to try to determine when thrombosis developed. Thrombosis can be considered recent when a thrombus is visible within the lumen of the portal vein and when there are no or minimal portoportal or portosystemic collateral veins. Computed tomography is most useful in this regard because spontaneous high luminal high density prior to any contrast medium injection indicates a thrombus dating back to less than 10 days. Conversely demonstration of a well-developed cavernoma usually indicates an old thrombosis. The third step in management should be an investigation of the factors favouring or precipitating thrombosis. The purpose of this investigation is to identify a condition amenable to treatment. Investigation of the local factors is based mainly on abdominal computed tomography with contrast medium injection. It can be completed by endoscopic ultrasound in some cases. Barium X-ray studies and endoscopy rarely uncover an intestinal 5 disease that was not clinically evident . Investigation of general thrombophilic factors must be extensive because an association of several factors is the rule rather than an exception 27. The treatment issues must be considered separately for acute and old portal vein thrombosis. In the treatment of acute portal vein thrombosis, the issue of anticoagulation is a central one. To what extent spontaneous repermeation can be expected is not known. Current experience suggests that spontaneous repermeation is possible but uncommon, whereas complete or extensive repermeation can be achieved with anticoagulant therapy in 50- 80% of patients 23,28,29,30 . The minimum duration of anticoagulation used in these studies was three months. Repermeation prevents ischaemic intestinal injury in the short term and extra hepatic portal hypertension in long term. The duration of anticoagulation should be given for at least 6 months, and then be continued if an underlying thrombophilia has been demonstrated or be stopped in other cases. Is there a place for aggressive therapeutic procedures such as thrombolytic agents, or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt placement coupled with fibrinolysis for portal vein thrombosis of recent onset? Current data are insufficient to evaluate the benefit/risk ratio of these procedures 5. The treatment of patients with old portal vein thrombosis is focussed on the control of acute bleeding episodes and attempts to prevent recurrent variceal haemorrhage. The available uncontrolled data indicate that the measures that are of established efficacy in patients with cirrhosis, namely propanolol and endoscopy therapy can be applied to patients with portal vein thrombosis 31, 32. However, there is a matter of concern about the use of vasoconstrictive agents in acute GI bleeds. Theoretically the profound decrease in splanchnic blood flow induced by bleeding and by the therapeutic vasoconstrictive agents might trigger recurrence or favour the extension of thrombosis in the portal venous system and precipitate intestinal ischaemia 5. Evidence on the benefit of anticoagulation and thrombolytic therapy in patients with chronic portal vein thrombosis with or without cirrhosis is lacking, and therefore cannot be recommended in such cases chronic 11 . A recent study portal vein 18 reported that anticoagulant therapy in thrombosis increased neither the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding nor the severity of bleeding. There were no deaths due to bleeding on anticoagulant therapy. The study further showed that recurrent thrombosis was efficiently prevented. However, further experience is needed, before advocating indiscriminate use of anticoagulant agents in patients with old portal vein thrombosis. References 1. Balford GW, Stewart TG. Case of enlarged spleen complicated with ascites, both depending upon varicose dilatation and thrombosis of the portal vein. Edinb Med J 1869; 14:589-98. 2. Henderson JM, Gilmore GT, Mackay GJ, et al. Haemodynamic during liver transplant: The interaction between cardiac output and portal venous and hepatic arterial flow. Hepatology 1992; 16:715-8. 3. Valla DC, Condat B. Portal vein thrombosis in adults: Pathophysiology, pathogenesis and management. A review. J Hepatol 2000; 32:865-71. 4. Cohen J, Edelman RR, Chopra S. Portal vein thrombosis: A review. Am J Med 1992; 92:173-82. 5. Valla DC, Condat B, Lebrec D. Spectrum of portal vein thrombosis in the west. J.Gastroenterol.Hepatol. 2000; 17:S224-S227. 6. Brown KM, Kaplan MM, Donowitz M. Extrahepatic portal vein thrombosis:Frequent recognition of associated diseases. J Clin Gastroenterol 1985;7:153-9. 7. Valla D, Casadevall N, Huisse MG, et al. Etiology of portal vein thrombosis in adults. A prospective evaluation of primary myeloproliferative disorders. Gastroenterology 1988;94:1063-9. 8. Rosendaal FR. Venous thrombosis: a multicausal disease. Lancet 1999;353:1167-73. 9. Egesel T, Buyukasik Y, Dundar SV, et al. The of natural anticoagulant deficiencies and factor V leiden in the development of idiopathic portal vein thrombosis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2000;30:66-71. 10. Mahomould AE, Elias E, Beauchamp N, Wilde JT. Prevalence of the factor V leiden mutation in hepatic and portal vein thrombosis. Gut 1997;40:798-800. 11. Sobhonslidsuk A, Reddy KR. Portal vein thrombosis: A concise review. Am J gastroenterol 2002;97:535-41. 12. Okuda K, Ohnishi K, Kimura K, et al. Incidence of portal vein thrombosis in liver cirrhosis. An angiography study in 708 patients. Gastroenterology 1985;89:279-86. 13. Witte CL, Brewer ML, Witte MH, Pond GB. Protean manifestations of pyelothrombosis. A review of thirty-four patients. Ann Surg 1985;202:191-202. 14. Bick RL. Coagulation abnormalities in malignancy. Semin Thromb Hemost 1992;18:353-72. 15. Orozco H, Takahashi T, Mercado MA, et al. Post operative portal vein obstruction in patients with idiopathic portal hypertension. J Clin Gastroenterol 1990;12:607. 16. Gayowski TJ, Marino IR, Doyle HR, et al. A high incidence of native portal vein thrombosis in veterans undergoing liver transplantation. J Surg Res 1996;60:333-8. 17. Belli L, Sansalone CV, Aseni P, Romani F, Rondinara G. Portal thrombosis in 1986;203:286-91. cirrhotics. A retrospective analysis. Ann Surg 18. Condat B, Pessione F, Hillaire S, Denninger MH, Guillin MC, Poliquin M et al. Current outcome of portal vein thrombosis in adults: Risk and benefit of anticoagulant therapy. Gastroenterol 2001;120:490-497. 19. Jaffe Y, Lygidakis NJ, Blumgart LH. Acute portal vein thrombosis after right hepatic lobectomy:successful treatment by thrombectomy. Br J Surg 1982;69:211. 20. Voorhees AB, Price JB. Extrahepatic portal hypertension. A retrospective analysis of 127 cases and associated clinical implications. Arch Surg 1974;108:338-41. 21. Plemmons RM, Dooley DP, Longfield RN. Septic thrombophlebitis of the portal vein(pylephlebitis): Diagnosis and management in the modern era. Clin Infect Dis 1995;21:1114-20. 22. Saxena R, Adolph M, Ziegler JR, et al. Pylephlebitis. A case report and review of outcome in the antibiotic era. Am J Gastroenterol 1996;91:1251-3. 23. Baril N, Wren S, Radin R, et al. The role of anticoagulant in pylephlebitis. Am J Surg 1996;172:449-53. 24. Webb LJ, Sherlock S. The aetiology, presentation and natural history of extrahepatic portal venous obstruction. Q J Med 1979;192:627-39. 25. Maddrey WC, Malik KCB, Iber FL, Basu AK. Extrahepatic obstruction of the portal venous system. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1968;127:989-98. 26. Alvarez F, Bernard O, Brunelle F, Hadchovel P, Odievre M, Alagille D. Portal obstruction in children.I. Clinical investigation and hemorrhage risk. J Pediatr 1983;103:696-702. 27. Denniger MH, Chait Y, Casadevall N et al. Cause of portal or hepatic venous thrombosis in adults: the role of multiple concurrent factors. Hepatology 2000;31:587-91. 28. Sheen CL, Lamparelli H, Milne A, Green I, Ramage JK.Clinical features, diagnosis and outcome of acute portal vein thrombosis. Q J Med 2000;93:531-534. 29. Condat B, Pessione F, Denniger MH, Hillaire S, Valla D. Recent portal or mesenteric venous thrombosis: Increased recognition and frequent recanalisation on anticoagulant therapy. Hepatology 2000;32(3):466-470. 30. Rahmouni A, Mathieu D, Golli M, Douek P, Anglade MC, Caillet H, Vasile N. Value of CT and sonography in the conservative management of acute splenoportal and superior mesenteric venous thrombosis. Gastrointest Radiol 1992;17:135-140. 31. Braillon A, Moreau R, Hadengus A, et al. Hyperkinetic circulatory syndrome in patients with presinusoidal portal hypertension. Effect of propanolol. J Hepatol 1989;9:312-8. 32. Kahn D, Krieg JE, Terblanche J, et al. A 15-year experience of injection sclerotherapy in adult patients with extrahepatic portal venous obstruction. Ann Surg 1994;219:34-9.