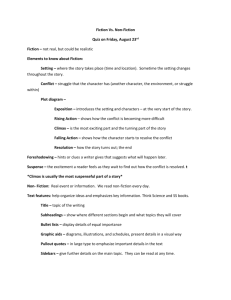

Thoughts on Story Structure

advertisement

Thoughts on Story Structure © Perry Glasser I. STRUCTURE – A descriptive definition of structure describes how the author manipulates time. Let’s define structure as the order of events. It follows that we when talk about structure in fiction, we are discussing two possibilities: Chronological Structure, and Narrative Structure Chronological structure refers to the events as they happened in time. Narrative structure refers to the events as the writer orders them for the reader. Chronological structures. The most natural structures are chronological. The events of a story are causally connected. Event A precipitates B, which precipitates C, which precipitates D, etc. “Event” here also means any quality of character. Huck leaves the safety of Hannibal not only because his lout of a drunken father shows up, but because 14-year-old Huck has considerable spine and is tired of being “civilised,” anyway. Causality is in this sense an aesthetic value that suggests one of the reasons we read and value literature is to enter and experience a world in which events make sense. Fiction is neat; life sloppy. That such a notion can set us off on a long philosophical conversation on the sudden and cruel turns of Fate and life’s seemingly random nature will not prevent us from disliking a story in which the characters are engaging, the plot taut, the writing faultless, and the story abruptly ended when all the characters are killed by a runaway bus. Alert graduate students will think of exceptions. Thomas Hardy and George Elliot, for examples, have their characters caught up in accidents of Fate—rivers flood their banks and sudden storms keep lovers apart—but the “pathetic fallacy” that has Nature perform in concert and in sympathy to characters is a staple of 19th century fiction that for modern sensibilities seems hokey. Similarly, understand that causality is like soft taffy. We can tug at it quite a bit and most readers will happily allow a degree of coincidence and accident to make the story work, but too much of this can make the taffy part. Okay, so the lovers meet by accident, and sure, they both went to the same college at the same time and never knew it, and, yes of course, they both married the same year and divorced after exactly the same interval, five years ago…Yes, we all know people who have had these amazing coincidences happen to them, BUT let’s always keep in mind that fiction is a more reasonable realm than reality. Fiction is explicable, life is not, and that fact that life gets weird can’t be a justification for fiction that gets weird, too. The taffy simply snaps. Finally, students should be wary of misunderstanding this point to be an appeal for fiction that takes place only in a naturalistic universe. The données of a story, that which is “given,” precede the beginning. In a fictive universe, we can have dogs talk and dragons fly—why not? A story begins, “Mary was obsessed by men with dark hair and blue eyes,” is under no obligation to tell us when, how and where the obsession originated. It is a “given.” That’s just Mary and that is who she is—now the story can go forward. Narrative Structures. Since we experience life in time, chronological structures are the natural way to tell a story, but for some stories, chronology may not be the best way to recount the tale. Students are well-advised not to vary chronological structure without very good reasons for doing so. Flashbacks, and flashbacks in flashbacks—whole scenes from the past designed to allow the reader to understand the present—are generally the sign of a writer “filling in” what the reader needs to know to comprehend the current action, and when handled amateurishly are an aesthetic defect. If the flashback is indeed more engaging than the present—why aren’t we simply reading that? If the flashback is necessary for the present action, why didn’t we simply start there? If the present action is engaging and exciting, why slam on the brakes? However, the aesthetic effects open to a non-chronological structure are rich. By and large, non-chronological structures are called for when the story has in it vast gaps in time, intervals in which nothing very interesting or formative happened, and so the writer has made the considered decision to exclude those intervals and to engage the reader with current action that raise questions and mystery. This may sound complicated, but examples in literature are numerous and make the case, and in mystery novels as a genre, are the whole ball of wax. Just how and why did that corpse come to be on the floor? Wuthering Heights begins with our meeting a psychologically tortured man haunted by the ghost of a woman named Catherine. Our vision is via a character named Lockwood, and when he falls ill, his nurse, Nelly tells him (and us) Heathcliff’s history, “that of a cuckoo.” It is no accident that the novel’s first word is a date—Bronte needs to place the characters in time. Our initial exposure to Heathcliff and the ghost of Catherine are the current action of the novel; that present is followed by the long multi-scene flashback that is Nelly’s narrative, and that is followed by a short return to the present in which we learn Heathcliff’s final fate. Thus, the novel’s narrative structure is: B—A—C while it’s chronological structure is, of course, A—B—C. Lord Jim is an expressionistic novel of character. Marlowe, Conrad’s narrator, observes Jim, and his deportment and manner raise a number if questions about Jim’s nature, and the nature of courage, questions that trouble Marlowe who wants to believe that Jim is “one of us.” Marlowe in his travels makes a point of asking many people what they know and understand of Jim, and gradually the reader (and Marlowe) learn a more complete picture. But none of the people Marlowe interviews can offer a complete portrait—they each knew Jim at a different time. Further, the order in which Marlowe gathers testimony about Jim is not an orderly rendering of the events of Jim’s life. The novel accumulates. Like a mosaic—up close, we see only tiles, but if we stand back and look at the entirety, we begin to see a picture. Hence, the label “expressionistic”—we are receiving multiple impressions of Jim, a mix of facts and judgments, and the quality of the impressions is not only a function of fact but of the character of the various tellers. This narrative structure makes what might be mistaken for a boy’s adventure novel set in the South Seas into a tour de force of narrative control; with each tale within the tale, Conrad has us reevaluate and reconsider what we know of Jim, our understanding of courage, and what it means to be “one of us.” II. STRUCTURE — a functional definition of structure enables us to talk about the parts of a story and what each part needs to do. No matter what time structure a writer employs, a story has 5 functional parts: Exposition Rising Action (also called “Complications”) Climax Falling Action (also called “Denouement”) Conclusion (or (Resolution”) Diagrammatically, the structure of a story is drawn as “Freitag’s Triangle.” (In the diagram reproduced below, “B—Introduction of conflict,” is a label for a turning point—I am far too lazy to draw our own version) http://www.aliscot.com/ensenanza/1302/freitag.gif The symmetry of this diagram should NOT confuse the student into believing the parts are of equal length. Each part has its function. Exposition—exposes the readers to time, place, initial characterization, and ends with the introduction of conflict. That is to say, a stable state of affairs in which characters had no motive to commence any dramatic action is disrupted. In a short story, the entire exposition could be dispensed with in a sentence. In a novel, a chapter. Frequently, the introduction of conflict occurs with an arrival or a departure—a character arrives and disrupts a stable situation, or a character departs a stable situation. Rhett Butler shows up; Ishmael decides to go to sea; aliens arrive on Earth; Napoleon invades Russia. Rising Action—causally connected attempts to alleviate the “voltage” or tension of the conflict are frustrated or do not meet with the usual, expected success, and these attempts not only reveal character because the characters are undergoing stress, but they change the personality of the protagonist. Mr. Butler not only seems impervious to flirtation, but the Civil War is breaking out. It’s all so inconvenient! The rising action of a story accounts for the bulk of the writing. The necessity of causality is an aesthetic value—without it, each incident seems disconnected from prior incidents. In a novel, the rising action could take hundreds of scenes and be about many characters. The protagonists might each be moving toward the same geographic or spiritual place, as in the film “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” or the novel, War and Peace. Each scene advances plot and, since character is revealed through action, each scene tells applies more stress to the characters so that they call upon new resources and thereby change who they are. “I shall never be hungry again!” declares Scarlet O’Hara, and since we have seen her suffer deprivation and death of people she loves and has had her entire world burn down around her, we know she means it. History has educated her. GWTW is in many ways a bildungs roman—a novel of education. A short story, on the other hand, might be about a single, dramatic encounter that changes personality, perhaps something as subtle as a revelation within consciousness, an epiphany. Remember: without a change in character, a story is by definition trivial—an anecdote. Climax—At the end of the chain of causally related events, there is a final inevitable confrontation between the antagonistic forces that generated the voltage of the conflict. That scene is the climax. It is “the most exciting” precisely because all the prior scenes have made it plain that there is no avoiding the confrontation and that the antagonists are equal to each other. We spend a lot of pages making sure we know that Scarlet and Rhett are equals (the book is far better than the film in this regard). She has gone from flirtatious twerp to hardened woman of the world, tempered in the forge of war. Moby Dick and Ahab are equals when they meet, so equal that their confrontation results in mutual destruction. The alert student will wonder about novels and stories in which characters are pitted against an uncaring, unrelenting merciless universe; Hemingway’s, for example, or novels by Camus. The art there is to have the reader engaged by the struggle and to cast the illusion that maybe, just maybe, Santiago can get that damned fish to shore, or that Lt. Henry and Catherine can have a love that survives despite World War I. In Camus, the character’s refusal to be engaged in struggle is their struggle, making them “existential heroes”; since their struggle is to not struggle, they seem heroic to those of us whose lives seem to be perpetual struggle. Any story without a climax leaves a reader with a vague sense of having been abused. “All this—and for what?” We sometimes call a climax a mandatory scene. Falling Action — In contemporary fiction, this is usually very brief. The stable situation with which the story began must be reinstated. If it isn’t, the story is not finished. Readers will ask, “Yeah, but what about…?” Characters left unaccounted for have to be accounted for, so Ishmael explains he is the only survivor because Queeg-Queeg’s coffin was watertight and so could float. The mysterious events of the past can now be explicated; dazed survivors step off the space ship—and maybe a tad melodramatically, mothers are reunited with their missing children. Resolution—Now what? Well, if you are Huck Finn, you let people know you are headed for the territories. If you are Ishmael, you decide to write the story of the Great White Whale. The point is to be sure readers know that “peace” is returned—which may not be the same as a happy ending. Peace may have been gained only through sacrifice; the church bells of Moscow ring not only because Napoleon is defeated, but to honor the dead. In a short story, resolution may indicate the new, perhaps discomforting, understanding gained by characters and, of course, by readers. Alert graduate students will think of the exceptions to this mechanical, Aristotelian-based analysis of structure. Such writers as Poe, who simply omitted Exposition and Rising Action, are critically interesting, but to a beginning writer are dangerous to emulate. Long before Picasso engaged Cubism and taught us to see the world anew, he was a fine draftsman who was capable of visually representative art. Walk before you try to run. As a student of the art, try to find a story that you can finish—you can learn about writing by composing fragments or pieces of a larger idea you will finish some other time, but you cannot learn about story structure.