Explicit performatives as holophoric speech acts: Why self

advertisement

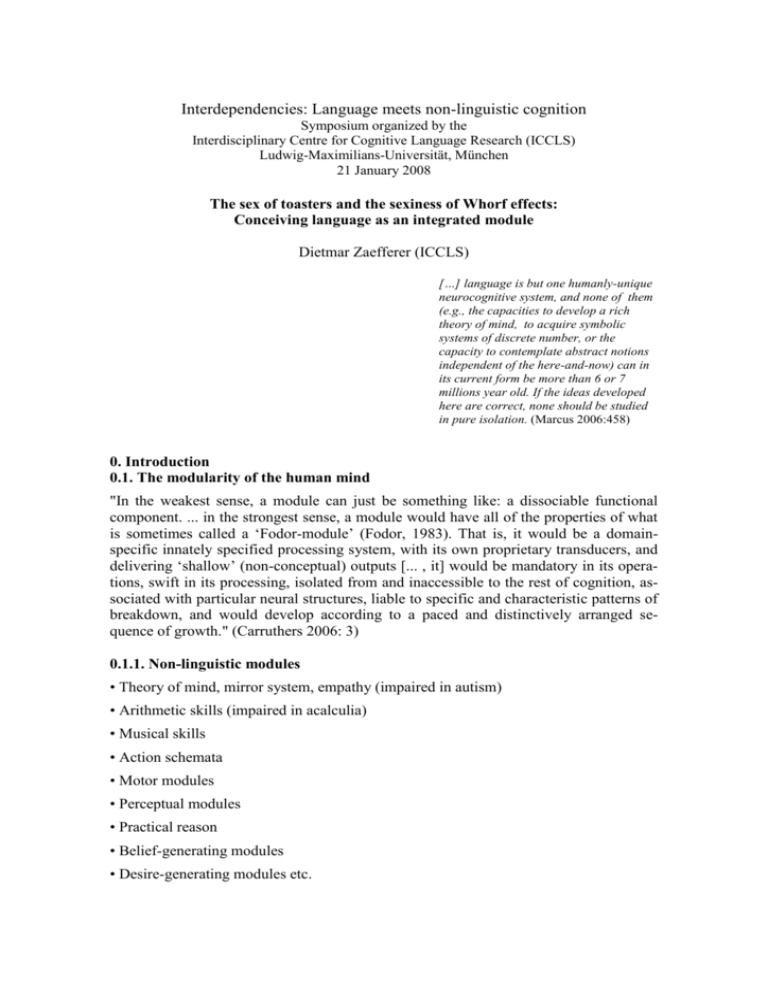

Interdependencies: Language meets non-linguistic cognition

Symposium organized by the

Interdisciplinary Centre for Cognitive Language Research (ICCLS)

Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, München

21 January 2008

The sex of toasters and the sexiness of Whorf effects:

Conceiving language as an integrated module

Dietmar Zaefferer (ICCLS)

[…] language is but one humanly-unique

neurocognitive system, and none of them

(e.g., the capacities to develop a rich

theory of mind, to acquire symbolic

systems of discrete number, or the

capacity to contemplate abstract notions

independent of the here-and-now) can in

its current form be more than 6 or 7

millions year old. If the ideas developed

here are correct, none should be studied

in pure isolation. (Marcus 2006:458)

0. Introduction

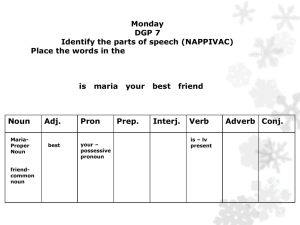

0.1. The modularity of the human mind

"In the weakest sense, a module can just be something like: a dissociable functional

component. ... in the strongest sense, a module would have all of the properties of what

is sometimes called a ‘Fodor-module’ (Fodor, 1983). That is, it would be a domainspecific innately specified processing system, with its own proprietary transducers, and

delivering ‘shallow’ (non-conceptual) outputs [... , it] would be mandatory in its operations, swift in its processing, isolated from and inaccessible to the rest of cognition, associated with particular neural structures, liable to specific and characteristic patterns of

breakdown, and would develop according to a paced and distinctively arranged sequence of growth." (Carruthers 2006: 3)

0.1.1. Non-linguistic modules

• Theory of mind, mirror system, empathy (impaired in autism)

• Arithmetic skills (impaired in acalculia)

• Musical skills

• Action schemata

• Motor modules

• Perceptual modules

• Practical reason

• Belief-generating modules

• Desire-generating modules etc.

Zaefferer

Language as an integrated module

0.1.2. The language module and the modules of language

Berinmo is a module in the mind every Berinmo speaker with the following submodules

{Berinmo-x | x Phonetics (elementary and compositional), Phonology (e, c), Lexicon(e, c), Morphology (e, c), Syntax (e, c), Semantics (e, c), Pragmatics (e, c)}

0.2. Interfaces in the mind

0.2.1. Internal interfaces of the language module

{x-y interface | x, y Phonetics (elementary and compositional), Phonology (e, c),

Lexicon(e, c), Morphology (e, c), Syntax (e, c), Semantics (e, c), Pragmatics (e, c)}

0.2.2. External interfaces of the language module

Language and the conceptual system (ontology)

Language processing and generalized Stroop-effects

Linguistic and non-linguistic phonetics

Signing and gesturing

1. Prelinguistic cognitive faculties

1.1. Phylogenetically prior faculties

The concept of an instrument in New Caledonian crows (Kenward et al. 2006)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TtmLVP0HvDg.

"Consider, for example, a honeybee’s thought with the content, [nectar is 200 meters

north of the hive] (or some near equivalent). Is this genuinely composed of the concepts

nectar, 200 meters (or some roughly equivalent measure of distance), north (or some

similar solar-based measure of direction), and hive? Well yes, because we know that

bees satisfy the weak causal Generality Constraint in respect of such concepts"

(Carruthers 2009)

1.2. Ontogenetically prior faculties

Infants encode the roles of agent and recipient in a triadic give-and-take interaction

from the age of 101⁄2 months. They perceive a role reversal as more relevant than a

direction reversal. (Schöppner, B. /Sodian, B. /Pauen, S., 2004)

2. Co-linguistic cognitive faculties

2.1. Interdependencies

Is the language module (module cluster) encapsulated or does it leak?

2.2. Linguistic expressions are concept activators of the third kind

The language of thought hypothesis claims:

(1) Cognitive processes consist in causal sequences of tokenings of internal representations in the brain.

I agree, except that I would replace tokenings by activations.

2

Zaefferer

Language as an integrated module

(2) These internal representations have a combinatorial syntax and semantics, and

further, the symbol manipulations preserve the semantic properties of the thoughts.

(Schneider 2008: 1)

I disagree, guided by William.

My view: Concepts enable their possessors to make distinctions required for decisionmaking, therefore they are

• primarily activated by their instances (what falls under the conccept) and

• secondarily by activations of associated concepts (activation propagation).

The shapes of linguistic signs are

• concept activators of a third kind that allow for controlled activation within and between individuals.

If linguistic signs are concept activators of the third kind, the analysis of a linguistic

should profit form a rigorous analysis of the concept or conceptual structure it activates.

The following, somewhat lengthy section is intended as a proof of the pudding, so

please bear with me.

2.3. Turn over control to ontology!

There are at least two reasons why control nouns are interesting for the given purpose:

1. Nominal control is a sadly understudied subject.

2. The ontological status of the control-related concepts should allow predictions about

argument sharing options independent of the syntactic category of the linguistic unit

that codes the head concept.

2.3.1. Conceptualizing the control relation

(1) Mariai plant, _i eine Bank auszurauben.

Maria plans

a bank to-rob

(2)

Mariai ist außerstande, _i eine Bank auszurauben.

Maria is incapable

a bank to-rob

(3)

Mariai fehlt der Mut, _i eine Bank auszurauben.

Maria

lacks the courage

a bank to-rob

Here is one formulation of the RRG theory of obligatory control (Van Valin 1999: 10)

(T 1) Theory of control for transitive matrix verbs in obligatory control constructions:

1. Causative and jussive verbs have Undergoer control.

2. All other verbs have Actor control.

To get rid of the category restriction refer only to content element:

(T 2) Theory of control for relational head concepts in obligatory control structures:

1. Concepts of causation and attempted causation have Undergoer control.

2. All other concepts have Actor control.

But then what does it mean for a concept to have control? Therefore, some terminological clarifications are required.

3

Zaefferer

Language as an integrated module

(D 1) Conceptual participant sharing (CPS)

A CPS relation holds between concepts H and D with respect to P1H and P1D

iff

(i) H has at least two distinct participant roles P1H and P2H,

(ii) D is the filler of P2H,

(iii) D has at least one participant role P1D, and

(iv) the filler of P1H and the filler of P1D have joint reference.

Note: H head concept; D dependent concept. Joint reference means that the referents (or

the tentative referents, with quantification) of the filling concepts not disjoint.

P2H

H

D

P1H

(X)i

P1D

(Y)i

(D 2) Conceptual control (CC)

A CC relation holds between concepts H and D with respect to P1H and P1D

iff

(i) a CPS relation holds between concepts H and D with respect P1H and P1D

(ii) at most one of the fillers of P1H and of P1D is specified.

Note: The specified filler of P1H or P1D is called the controller (cR), the unspecified

filler of P1D or P1H is called the controllee (cE).

(D 2.1) Conceptual downward control (CDC)

A CDC relation holds between concepts H and D with respect to P1H and P1D

iff

(i) a CC relation holds between concepts H and D with respect to P1H and P1D

(ii) only the filler of P1H is specified.

Note: Since the controller fills a participant role of the head concept and the controllee

one of the dependent concept, the direction of control is downward.

P1H

H

P1H

Xi

D

P1D

__i

(D 2.3) Conceptual cross-control (CCC)

A CCC relation holds between concepts H and D with respect to P1H and P1D

iff

(i) a CC relation holds between concepts H and D with respect to P1H and P1D

(ii) none of the fillers of P1H and of P1D is specified.

Note: In the absence of specification of fillers no way of deciding direction of control.

4

Zaefferer

Language as an integrated module

P2H

H

D

P1H

__i

P1D

__i

Arbitrary, generic control; free, nearly free control (Culicover and Jackendoff 2006):

(6)

Eva weiß nicht, was es heißt, _a glücklich zu sein.

Eva knows not what it means happy to be

2.3.2. Control nouns and control chains

(7)

a. Mariai fehlt der Mut, _i eine Bank auszurauben.

Maria lacks the courage a bank to-rob

b. Mariai imponiert der Mut, _a eine Bank auszurauben.

Maria impresses the courage a bank to-rob

A control noun construction that involves only a single head concept:

(8)

Mariasi Mut, _i eine Bank auszurauben.

Maria's courage a bank to-rob

Conceptual downward control (U_GOER is short for UNDERGOER, P_OR for POSSESSOR):

CONTENT

U_GOER

COURAGE

ROB

P_OR

Mariai

BANK

ACTOR

__i

(P_UM: POSSESSUM, STIM: STIMULUS, B_IMP: BE_IMPRESSED_BY; EX_ER: EXPERIENCER):

(7)

a. Mariai fehlt der _i Mut, _i eine Bank auszurauben.

Maria lacks the courage a bank to-rob

P_UM

LACK

P_OR

Mariai

CONTENT U_GOER

COURAGE

ROB

BANK

P_OR

__i

ACTOR

__i

b. Mariai imponiert der _a Mut, _a eine Bank auszurauben.

Maria impresses the courage a bank to-rob

STIM

B_IMP

CONTENT U_GOER

COURAGE

ROB

BANK

EX_ER

Mariai

P_OR

__a

ACTOR

__a

5

Zaefferer

(9)

Language as an integrated module

a. Karli gab/nahm/neidete Mariak die kChance, _k vorzusingen.

Karl gave/took/begrudged Maria the opportunity to_audition

b. Karli erhielt von Mariak die iChance, _i vorzusingen.

Karl received from Maria the opportunity to_audition

2.3.3. Control problems

2.3.3.1. Controller choice options

Minimal Distance Principle (MDP; Rosenbaum 1967): The syntactic controller is the

minimal c-commanding DP of the embedded subject.

(12) a. Eine iGarantiek, _i heute noch zu liefern, hat unsk die Firmai nicht gegeben.

A

warranty

today still to deliver has to-us the company not given

b. Eine iGarantiek, _i heute noch zu liefern, wurde unsk _i nicht gegeben.

A

warranty

today still to deliver

was

to-us not given

c. Eine iGarantiek, _i heute noch zu liefern, hat _k die Firmai nicht gegeben.

A

warranty

today still to deliver has the company not given

d. Eine iGarantiek, _i heute noch zu liefern, wurde _k _i nicht gegeben.

A

warranty

today still to deliver

was

not given

(T 2) correctly predicts the Actor and not the Undergoer as the controller.

(13) a. Der Konventk hat unsi kein kMandati erteilt, _i dies zu tun.

The convent has to-us no mandate issued this to do

b. Unsi wurde _k kein kMandati erteilt, _i dies zu tun.

To-us was

no mandate issued this to do

c. Der Konventk hat _i kein kMandati erteilt, _i dies zu tun.

The convent has

no mandate issued this to do

d. Es wurde _i _k kein kMandati erteilt, _i dies zu tun.

EXPL was

no mandate issued

this to do

(T 2) correctly predicts the Undergoer and not the Actor as the controller.

(14) a. Ichi hatte die iEhre, _i ihn kennenzulernen.

I

had the honor him to-get-to-know

b. Erk erwies miri die iEhre, _k zur Premiere zu kommen.

He accorded me the honor to-the premiere to come

c. Erk erwies miri die iEhre, _i zur Premiere kommen zu dürfen.

He accorded me the honor to-the premiere come to be-allowed

(T 2) predicts Undergoer control, incorrectly for (14) b., correctly for (14) c.

2.3.3.2. Controller choice variation

(15) Eine iGarantiek, _k dies sofort mitnehmen zu können, erteilen siek _i leider nicht.

A

warranty this immediately take-away to be-able give they unfortunately not

(16) Der iDruckk der Tochteri auf die Elternk, _i alleine ausgehen zu dürfen, wuchs.

The pressure of-the daughter on the parents alone go-out to be-allowed increased

6

Zaefferer

Language as an integrated module

(15) has Undergoer control and (16) has Actor control against (T 2).

(17) a. Das iGesuchk des Häftlingsi an den Richterk, _k ihni zu entlassen, überraschte.

The plea

of-the inmate on the judge

him to release

surprised

b. Das iGesuchk des Häftlingsi an den Richterk, _i entlassen zu werden,

The plea

of-the inmate on the judge

released to PASSIVE

überraschte.

came-as-a-surprise

2.3.4. An ontology-based theory of conceptual control

A basic tenet of ontology-based linguistics (Schalley and Zaefferer 2007):

(P)

Container shape follows content structure.

A methodological corollary of (P) is (M):

(M) A thorough ontological analysis tends to pay off.

(18) Der iDruckk der Tochteri auf die Elternk, _k CAUSE _k/i/k+i/*a pünktlich zurück zu

The pressure of-the daughter on the parents

punctually back to

sein, wuchs.

be increased

(16)' Der iDruckk der Tochteri auf die Elternk, _k CAUSE _i alleine ausgehen zu dürfen,

The pressure of-the daughter on the parents

alone go-out to be-allowed

wuchs.

increased

(17) b.' Das iGesuchk des Häftlingsi an den Richterk, _k CAUSE _i entlassen zu werden,

The plea

of-the inmate on the judge

released to PASSIVE

überraschte.

came-as-a-surprise

(14) b. Erk erwies miri die iEhre, _k zur Premiere zu kommen.

He accorded me the honor to-the premiere to come

(14) a. Ichi hatte die iEhre, _i ihn kennenzulernen.

I

had the honor him to-get-to-know

Arbitrary control in (20) because there is no possible Controller in the matrix clause:

(20)

Es ist immer eine aEhre, _a einen Nobelpreisträger kennenzulernen.

It is always an honor

a king to-get-to-know

To find out what is wrong with (T 2), the minimal pair in (21) will be helpful.

(21) a. Erk verschaffte miri die iGenugtuung, _k zur Premiere zu kommen.

He provided me the gratification to-the premiere to come

b. Erk verschaffte miri die iMöglichkeit, _i zur Premiere zu kommen..

He provided me the possibility to-the premiere to come

Terminological regulation: If participant A transfers c-control to participant B we say A

has indirect control, else he has direct control:

7

Zaefferer

Language as an integrated module

(T 3) Control-by-control theory of participant sharing

p-control (covert participant sharing) is controlled by c-control (causal control) in

the following way:

If no participant of the head concept c-controls the dependent concept, p-control is

arbitrary,

else the participant of the head concept which most directly c-controls the dependent concept is the p-controller.

(9)

a. Karli gab/nahm/neidete Mariak die kChance, _k vorzusingen.

Karl gave/took/begrudged Maria the opportunity to_audition

b. Karli erhielt von Mariak die iChance, _i vorzusingen.

Karl received from Maria the opportunity to_audition

2.3.5. Summary

Starting from the example of non-deverbal infinitive governing nouns in German we

have come to see that a general theory of control has to integrate several factors, some

of which are purely conceptual and some of which are language-specific. (P) Ontologygrammar interaction: Ontology proposes, grammar disposes

The basic properties of diverse control constructions can be fairly correctly predicted

from a thorough ontological analysis of the concepts involved and a very simple principle that connects participant control with causal control in the sense of potential influence.

Not the mere presence versus absence of real or potential c-control is decisive for pcontroller choice, but the question which of the potential c-controllers has the most immediate power over an instantiation of the dependent concept. Control problems arise

out of category mismatches, but even in the repair mechanisms the validity of our theory is reflected.

3. Language strikes back: Whorf effects

3.1. Domains of Whorf effects

“We dissect nature along lines laid down by our native language. The categories and

types that we isolate from the world of phenomena we do not find there because they

stare every observer in the face; on the contrary, the world is presented in a kaleidoscope flux of impressions which has to be organized by our minds—and this means

largely by the linguistic systems of our minds.” (Whorf, Benjamin Lee, 1956)

Frames of Reference: Levinson

Color words:

Kay, Roberson, Regier ...

Past tense:

English vs Indonesian (Boroditsky, Ham, Ramscar 2003)

Grammatical gender:

German vs Spanish (Boroditsky, Schmidt, Phillips 2003)

Metaphor of time:

Boroditsky

Numbers:

Xu & Spelke (2000)

Vowels of attraction:

Jim > John, Judy > Jill (Perfors 2004)

8

Zaefferer

Language as an integrated module

3.2. The sex of toasters

Anecdotal evidence: "You obviously can't name a toaster George. That's just ludicrous.

Toasters are obviously feminine!"

3.3. No dramatic effect on thought?

“There is no scientific evidence that languages dramatically affect their speakers’ way

of thinking.... The idea that language shapes thinking seemed plausible when scientists

were in the dark about how thinking works or even how to study it. Now that cognitive

scientists know how to think about thinking, there is less of a temptation to equate it

with language....” (Steven Pinker 1994)

“Does language have a dramatic effect on thought in some other way than through

communication? Probably not.” (Bloom & Keil 2001)

“I hate [linguistic] relativism more than I hate anything else, excepting, perhaps, fiberglass powerboats.” (Jerry Fodor 1985)

The great attractivity of this idea for laypersons may have bolstered Whorf scepticism

among scientists. But since Lera Boroditsky and collaborators at Stanford University

have demonstrated the influence of arbitrary gender assignment on association with sexrelated features even in non-linguistic experiments, providing thus the arguably most

convincing evidence for the reality of such effects, the object of scepticism has shifted

from the existence to the strength of this influence.

The existence of such effects gives additional support to the concept of language as a

module of cognition that is integrated into a network of mutual dependencies.

4. Conclusion: Researching language as an integrated module

To study language as an integrated module at the object level requires at the metalevel a

conception of linguistics as an integrated module in the context of neighboring modules

of the big enterprise of cognitive science.

9

Zaefferer

Language as an integrated module

5. References

Boroditsky, L. /Schmidt, L. /Phillips, W., 2003: Sex, Syntax, and Semantics. - In Gentner and GoldinMeadow (eds), Language in Mind: Advances in the study of Language and Thought, MIT Press:

Cambridge, MA.

Carruthers, Peter, 2006. The Architecture of the Mind: massive modularity and the flexibility of thought.

Oxford: OUP, 2006.

Carruthers, Peter, 2009. Invertebrate concepts confront the Generality Constraint (and win). In R. Lurz

(ed.), The Philosophy of Animal Minds. Cambridge: CUP. (Draft. Comments welcome.)

Chomsky, Noam, 2007: Of Minds and Language. Biolinguistics 1: 09–27.

Culicover, Peter W. and Jackendoff, Ray, 2006. Turn over control to the semantics! Syntax 9:6, 131–152.

Evans, Nicholas D., 1995: A grammar of Kayardild. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Fodor, Jerry A. 1983. The Modularity of Mind. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kenward, Ben/Rutz, Christian/Weir, Alex A.S./Kacelnik, Alex, 2006: Development of tool use in New

Caledonian crows: inherited action patterns and social influences, Animal Behaviour, 72/6, 13291343.

Levin, Beth/Rappaport Hovav, Malka, 2005: Argument Realization. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Majid, Asifa, 2008: Constraints on Event Semantics across Languages. Abstract for the Workshop Foundations of Language Comparison: Human Universals as Constraints on Language Diversity, Bamberg, 27.-29.03.2008.

Marcus, Gary F. 2006. Cognitive architecture and descent with modifications. Cognition 101, 2, 443-465

Papafragou, Anna, to appear. Relations between language and thought: Individuation and the count/mass

distinction. in C. Lefebvre & H. Cohen (eds.), Handbook of Categorization in the Cognitive Sciences.

Elsevier.

Perfors, Amy 2004. What's in a Name? The effect of sound symbolism on perception of facial attractiveness. Poster presented at the 26th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society. Chicago, Illinois

Poeppel, David, 2005: The interdisciplinary study of language and its challenges. - In Grimm, D. (ed.),

Jahrbuch des Wissenschaftskollegs zu Berlin, Germany.

Poeppel, David/Embick, David, 2005: Defining the relation between linguistics and neuroscience. - In

Cutler, A. (ed.), Twenty-First Century Psycholinguistics: Four Cornerstones, Lawrence Erlbaum.

Pollard, Carl/Ivan A. Sag, 1994: Head-driven Phrase Structure Grammar. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Schalley, Andrea/Zaefferer, Dietmar (eds.), 2007: Ontolinguistics. How Ontological Status Shapes the

Linguistic Coding of Concepts. Berlin, New York: de Gruyter.

Schmidt, Lauren A. 2006. Language and Thought. 18.05.2006. http://www.mit.edu/~lschmidt/

people.csail.mit.edu/brussell/courses/9.012/LectureNotes/language_and_th___ght_lecture.ppt

Schneider, Susan, 2008. The Language of Thought. Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Psychology,

Paco Calvo and John Simons, eds.

Schöppner, B. /Sodian, B. /Pauen, S., 2004: Encoding action roles in meaningful social interaction in the

first year of life. Poster presented at the International Conference on Infant Studies, Chicago, IL.

Zaefferer, Dietmar, 2007: Language as mind sharing device. Mental and linguistic concepts in a general

ontology of everday life. - In: Schalley, Andrea C. /Zaefferer, Dietmar (eds) 2007, Ontolinguistics.

How ontological status shapes the linguistic coding of concepts, Berlin: de Gruyter, 189-222.

10