Omak Biosolids Composting Facility

advertisement

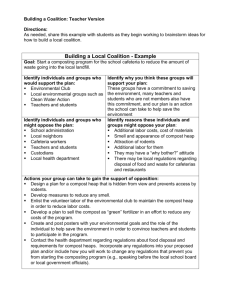

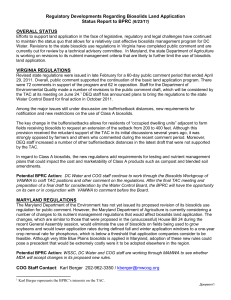

Category: Winner or Honorable Mention: Title of the Project: City: Population: Name: Title: Phone: General Omak Biosolids Composting Facility Omak 4,545 Theadore W. Pooler Project Engineer 509-966-7000 City of Omak Biosolids Composting Facility May 13, 2002 Omak implemented a Biosolids composting program to provide beneficial reuse of the sludge (biosolids) produced at our wastewater treatment plant and used a solid waste product that would otherwise go to the landfill. We tell our success story below. What it is-Why it was Needed Biosolids are a by-product of the wastewater treatment process. The Washington Department of Ecology encourages beneficial reuse of biosolids, and developed regulations and standards to protect the public and the environment when biosolids are reused. Unfortunately, our older method of handling biosolids did not meet the new State or Federal regulations. We applied untreated liquid biosolids to our 200-acre land application site. Little pathogen treatment occurred and there was no direct beneficial use of the material. Handling the liquid biosolids was also difficult and expensive. We pumped sludge into a tanker truck and hauled it to the land application site, so we were hauling large volumes of water to dispose of the small quantitiy of biosolids produced by the wastewater treatment process. Land application was impossible during the winter, or when the ground was too wet for spreading with the tanker truck. Therefore, we had to keep excess solids in the treatment process, limiting our treatment plant capacity and pushing the limits of our Ecology permit to discharge to the Okanogan River. Omak had to find a cost-effective means for treating and disposing of our biosolids. Our engineer, Huibregtse, Louman Associates, Inc. looked at options. They considered treatment to meet Federal standards for Class B biosolids, which are suitable for application on agricultural land, provided site access is restricted and certain food crops are not grown. They also considered treatment to meet standards for Class A biosolids, which have a higher level of pathogen removal and can be distributed to the public. After weighing the options and costs, and accounting for the increasing concerns about the use of Class B biosolids, the City council decided to move forward with biosolids composting. Though more expensive than the Class B options, we went with a biosolids treatment process that provided both a higher level of treatment and the greatest potential for beneficial reuse. We use the Containerized Compost System™, developed by Engineered Compost Systems, of Seattle Washington, to treat our biosolids. Dewatered sludge, known as biosolids, is mixed with amendment (wood chips, sawdust, and ground yard waste) and placed into 40 cubic yard containers, where it is treated under controlled conditions to produce composted Class A biosolids suitabel for public use. The Federal regulations (40 CFR 53) and State regulations include invessel composting as an approved process to further reduce pathogens in biosolids. How it Operates The Omak wastewater treatment process produces waste acitivated sludge. This necessary by product is 1.5% biological solids (biosolids) and 98.5% water. For use in composting, most of the water must be removed. The waste activated sludge is pumped to a belt filter press that removes 90% of the water, and the water is returned to the treatment plant for further treatment. We then conveyed the biosolids to our 325 cubic foot mechanical auger mixer where we combined them with amendment according to special “recipes” developed by our treatment plant operators. These “recipes” optimize the moisture content and particle size necessary for the airflow and bacterial growth needed for successful composting. Batches of the mixture are placed in the compost containers for 20 days of processing. We screen the cured compost and the final product is a high-quality soil additive. Key features of our composting process are: In-vessel composting, using the Containerized Compost System™ provides an enclosed treatment system. Enclosed systems control odors, improve process control, provide product consistency, and operate in cold weather. We have a readily available, low cost supply of amendment. The local lumber mill has excess wood chips and sawdust, which would otherwise go to waste. Omak also obtains free wood chips and ground yard waste from area landscapers and City maintenance crews. The Containerized Compost System™ uses computerized process monitoring to control the composting. Probes inserted into the containers monitor temperatures, and airflow through the containers is automatically adjusted to maintain optimum composting conditions. The City is assured regulatory compliance since the system records the temperatures to document that the process meets treatment standards. We have six 40 cubic yard containers that local roll-off trucks, used to transport the large garbage containers, can move. We contract with a local hauler for occasional trips to the site, and did not have to buy our own truck. Two more containers can be added in the future. Compost is kept in the containers for about 20 days. Heat from the composting kills the pathogens, and decomposition breaks down the biosolids and amendment into a useable material. Excess heat from active containers warms other containers, helping with start-up. Waste air passes through a simple biofilter, containing treated compset, to remove odors. After the 20 days of treatment, we screen the compost. Fine, useable material passes throught the screen and is collected for the final use. The coarse material is discharged separately and reused as part of the mixing “recipe”. What it costs General Industries, Inc.of Spokane, constructed the improvements for $595,000. This price includes the compost mixing building, the compost control building, concrete slabs, and the compost equipment. We found the compost equipment is sales tax exempt per WAC 458-2013601, since the City purchased the equipment for direct use in a manufacturing operation. We incur annual cost for electric power and one person, who also shares time with other treatment plant operations. Estimated annual operating costs are $35,000. We can sell the compost, but are still developing the market. Annual revenue from compost sales will not offset the operating costs, but it should provide the City $8,000 to $12,000 per year. How it Benefits the Community Biosolids composting meets the Department of Ecology’s goal for beneficial reuse of biosolids. We chose to go the extra step to meet the Class A treatment standards because it opens other opportunities for beneficial use. Composting benefits our community in the following ways: We provide a low-cost biosolids product (compost) for community use. The Class A biosolids have a low pathogen content and are suitable for direct distribution to the public. The City actively demonstrated the visability of the material, using it in City landscape areas and parks. Commercial landscapers use the material extensively for a variety of their soil ammendment needs, including lawn preparation and flowerbeds. The public is using the materials in gardens and flowerbeds. We can put 300,000 pounds (dry weight) of biosolids to beneficial use, rather than putting untreated solids on a land application site with no real benefit. Compost improves Eastern Washington soils. By increasing the organic content of the soil, our compost aids in moisture retention and improves workability. Though compost has a low nitrogen content, it does provide a slow-release form of nitrogen to augment plant fertilizer needs. Compost is sold to the public to generate revenue for the sewer fund. Frequently, communities incur costs for disposal of Class B biosolids. Our composting process uses a wasted wood product (chips and sawdust) that is of no use to the lumber industry. Though most of the wood chips and sawdust generated at the mill are put to use, a portion must be wasted. We use that waste product. We also use ground yard waste and put it to beneficial use, rather than sending it to the landfill. By using these combined sources of amendment, we divert about 2,100 cubic yards of material away from the landfill waste stream.