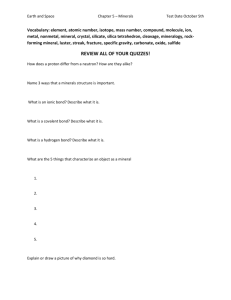

Interpreting Mineral Reservations

advertisement

Interpreting Mineral Reservations The Duhig Rule me Author i'i Ike Howard received ii r1,jr,1h(`V a �� ri? Y By Mike Howard Background ^?}ai�5 the University of Oklahoma 1n i Gb�c'� r obtained ajuris doctorate degree in la v Syr; Okla n University in 1975. Howard passed ti Pj r? ;;fT11 �' 1 He began his career as an in-house lend.,511 In 19,75 is Oil Company in Denver, Colorado, Ho,�. � rd was tin r rr r,3 for Post Petroleum Co., Inc. in Oklahoma City for rig C yeas (19)9 1987), In addition to working in-house for several o°tzr 41e r eri he has three years of independent field land erperer:e. i ie f5 currently employed in the land adminisiradon department rr-r Unocal Corp., Houston, Texas. he Duhig Rule originated from a 1912 Orange County, Texas, deed Tinterpreted by the Texas Supreme Court in 1940. The significance of the Duhig Rule is that it is followed in the majority of oil and gas jurisdictions. Louisiana adopted the Duhig Rule in the case of Dillon v. Moran (362 So. 2d 1130, La. App. 2d Circuit, 1978); Oklahoma adopted it earlier (Murphy v. Athans, 265 P2d 461, 1954). According to Williams and Meyers in section 311 of their commentary on oil and gas law, other states adopting the Duhig Rule are: Alabama, Colorado, Mississippi, North Dakota and Wyoming. Statement of the Duhig Rule The Duhig Rule of interpreting mineral reservations is applied to conveyances of mineral ownership by warranty or mineral deed (but not quitclaim deed) in which the owner of a fractional mineral interest reserves a fractional share of the mineral estate without also stating in the deed that there are outstanding mineral interests. The effect of the rule is to estop the grantor, by his warranty, from claiming the total fractional share of the minerals he reserved in the deed. Facts of the Case Duhig was the grantee of a Warranty Deed wherein his grantor reserved 1/2 of the mineral rights. Thus, at the time Duhig made his conveyance he was the owner of the surface and 1/2 of the minerals. In trying to clarify what occurred in the case, the author obtained a copy of the deed from Orange County. The following references to that deed point out the major clauses where Duhig failed to except the 1/2 mineral interest reserved by his grantor. First, the granting clause contains words of grant and describes the property being conveyed. Second, the clause which begins "To Have and to Hold" is the habendum clause which defines the duration of the interest. Third, the warranty clause begins "Warrant and forever defend..." Duhig attempted to reserve 1/2 of the minerals to himself. According to the case that clause reads: "But it is expressly agreed and stipulated that the grantor herein retains an undivided 1/2 interest in and to all mineral rights or minerals of whatever description in the land." Duhig's contention was that the above language reserved 1/2 of the minerals to him and that since 1/2 of the minerals were previously outstanding, his grantee received only the surface estate. The grantee contended that Duhig's deed conveyed the surface and 1/2 of the minerals leaving Duhig with nothing. The court held for Duhig's grantee, noting that his warranty covered the entire surface and mineral estate. Although his reservation showed an intent to reserve 1/2 of the minerals, Duhig could not warrant title to the entire mineral interest and also reserve 1/2 of the minerals without breaching his warranty (because of the outstanding 1/2 mineral interest). Since both intentions could not be given effect the covenant of warranty operated to estop Duhig from claiming the 1/2 mineral interest. 21 J. FRED HAMBRIGHT, CPL Kansas' only Aggie Landman AAPL WAPL Oil & Gas Lease Acquisitions KANSAS - NEBRASKA - COLORADO E L125 N. Market #1415 Wichita, Kansas 67202 (1) the field landman faces the problem in record checking and leasing; (2) the in-house landman faces the problem when a drilling or division order title opinion notes the problem as a title requirement; (316) 265-8541 (3) the lease or division order analyst may encounter the problem in processing changes of ownership. Competing Rule Aworkforce on-demand with the skills you need right now.: Outsourcing... Contract Work... ' Land & Property Management Lease & Division Order Maintenance & Disbursements Payrolling Payroll Administration `Temporary & Permanent Placement Title Research & Curative " Abstracts of Title * Oil & Gas Leasing Seismic Permitting Right of Way Acquisitions " Due Diligence LandTemp, Inc. 2650 Fountainview, Suite 235 President Houston, Texas 77057 (713 974-LAND Fax (713) 974-2053 Sandra G. Allen, CPL Due Diligence Duhig rule, it would be advisable to secure a Stipulation of Interest and Cross-Conveyance and have the document recorded to give third parties notice of the intention of the parties. You will, of course, also need to obtain a rental division order or 7rgmP Michael H. Mann, CPL Another complicating factor is that, in the absence of a dispute, the intention of the parties is controlling. In order to harmonize both rules, you should contact the parties involved, if possible, to understand their intent. Should that intent be contrary to the transfer order depending on whether the lease is undeveloped or producing. Do not hesitate to contact an attorney or in-house counsel if you have any questions. Summary A basic premise in understanding the Duhig rule is that the court first looks to make the grantee whole before allowing the grantor to reserve what is left. Example #1: Third Party owns 2/8 of the minerals. Grantor conveys to Grantee by Mineral Deed all right, title, and interest. In the deed, Grantor reserves 3/8 of the minerals to himself but makes no mention in the deed of the outstanding 2/8 interest. Result: The Grantee gets 5/8 of the Example #2: Third Party owns 3/8 of the minerals. Grantor owns the balance. Grantor conveys to Grantee all right, title and interest by Warranty Deed and makes no mention of the outstanding 3/8 mineral interest. Grantor reserves 1/4 of the minerals. Result: Third Party still has 3/8 of the mineral interest, Grantee receives 5/8 and the Grantor ends up with nothing. minerals. Third party owns 2/8 of the minerals, and Grantor is left with 1/8. Rationale: Grantor attempted to reserve 1/4 of the minerals but there was Rationale: The Grantor warranted title to all of the minerals and attempted to convey 5/8 of the minerals to Grantee and reserve 3/8 to himself. Since the Grantee was to receive 3/4 of the minerals, there has been a breach of warranty with the Grantee being Since there was no language in the deed excepting the outstanding 2/8 mineral interest, this portion was taken out of the Grantor's share. 22 already 3/8 which was not excepted. made whole to the extent possible. How Does This Rule Apply to Me? A Duhig-type deed can arise (and confound) any type of land professional: Since recognition of the problem is often half the battle, be alert when examining title to the following circumstances in which the Duhig rule applies: (1) the instrument is a warranty or mineral deed (not a quitclaim with no warranty of title); (2) less than the entire mineral ownership is being transferred (i.e., grantor is reserving part of the mineral interest); (3) the Grantor owns less than the entire mineral interest at the time of conveyance; (4) nowhere in the deed does the Grantor indicate that he is excepting from the warranty any prior reservations or conveyances of record. Landman / September/October 1996 Prior History: Error to the Court of Civil Appeals for the Ninth District, having reference to the previously severed and reserved mineral interest. judgment of the trial court and rendered in an appeal from Orange County. Buckner v. Keny, 109 S.W. (2d) (119 S.W. (2d) 688.) 361; Sun Oil Co. v. Burns, 125 Texas 549, 84 S.W. (2d) 442; Klein The ownership by Gilmer's estate, and its assignees, of an undivided v. Humble Oil & Refining Co. 67 one-half interest in the minerals in S.W. (2d) 911. A. M. Huffman, of Beaumont, for defendant in error. the land through the reservation in the Baker, Botts, Andrews & Wharton, Jesse Andrews, Fulbright, Crooker & Freeman, John H. Freeman, Leon Jaworski, and C. A. Leddy, all of error, Mrs. Duhig and others, make no claim of title to the surface estate, but their contention, sustained by the trial court and denied by the Court of Civil Appeals, is that W. J. Duhig, their predecessor, reserved for himself in his Suit by Peavy-Moore Lumber Company against Mrs. W. J. Duhig and others for the title and possession of 574 3/8 acres in the Jordan Survey, in Orange County, Texas. Further statement of the facts will be found in the opinion. The trial court rendered judgment for the plaintiff lumber company for the title and possession of the land but not as to the mineral rights. This judgment was reversed by the Court of Civil Appeals which rendered judg- ment in favor of the lumber company for the entire fee including the minerals, 119 S.W. (2d) 688, and the defendants have brought error to the Supreme Court. The case was submitted to the court sitting with the Commission of Appeals and an opinion written by Mr. Judge Smedley of the Commission was adopted as the opinion of the court. The judgment of the Court of Civil Appeals was affirmed. Counsel: Strong, Moore & Strong, K. W. Stephenson and Oscar C. Dancy, Jr., all of Beaumont, for plaintiffs in error. Where a deed reserved to the grantor a one-half interest in the minerals in and under said tract of land, thereby severing same from the surface right, a subsequent deed by the said vendee could not be construed as conveying all the minerals under said land, because the description in the deed of the term "all that certain tract or parcel of land," did not include the previously reserved one-half mineral interest, and therefore said subsequent reservation of the one-half mineral interest cannot be construed as an exception and as Landman / September/October 1996 Houston, filed briefs as amici curiae. Opinion by Smedley Through conveyance from the executor of the estate of Alexander Gilmer, deceased, W. J. Duhig became the owner of the Josiah Jordan Survey in Orange County, subject, however, to reservation by the grantor of an undivided one-half interest in the minerals. Thereafter Duhig conveyed the survey to Miller-Link Lumber Company, and in the deed it was judgment in favor of that company. ifrst deed, which was duly recorded, is admitted by the parties. Plaintiffs in conveyance of the land to Miller-Link Lumber Company the remaining undivided one-half interest in the minerals. Defendant in error, Peavy-Moore Lumber Company, takes the position that the deed last referred to did not reserve to or for the grantor such remaining one-half interest in the minerals, but that it in effect excepted only the onehalf interest that had theretofore been reserved by Gilmer's estate and invested agreed and stipulated that the grantor retained an undivided one-half interest the grantee with title to the surface estate and an undivided one-half interest in all of the mineral rights or minerals in the minerals. The deed from W. J. Duhig to MillerLink Lumber Company is a general warranty deed, describing the property in and on the land. Peavy-Moore Lumber Company became the owner of whatever title and estate Miller-Link Lumber Company acquired by the deed from Duhig in 574 3/8 acres of the said survey. The suit is by defendant in error, Peavy-Moore Lumber Company, against plaintiffs in error, Mrs. W. J. Duhig and others, who claim under W. J. Duhig, for the title and possession of the 574 3/8 [**8791 acres in the Jordan Survey. The trial court's judgment was that the plaintiff, Peavy-Moore Lumber Company, recover the title and possession of the land, except all minerals and mineral rights therein, and that as to the minerals and mineral rights, it take nothing against the defendants. On appeal by Peavy-Moore Lumber Company, the Court of Civil Appeals reversed the conveyed as that certain tract or parcel of land in Orange County, Texas, known as the Josiah Jordan Survey, further identifying [*5061 the land by survey and certificate number and giving a description by metes and bounds. After the metes and bounds, the following matter of description is added: "* * * and being the same tract of land formerly owned by the TalbotDuhig Lumber Company, and after the dissolution of said company, conveyed to W. J. Duhig by B. M. Talbot." After the habendum and the clause of general warranty and constituting the last paragraph in the deed, appears the following: "But it is expressly agreed and stipulated that the grantor herein retains an undivided one-half interest in and to all mineral rights or minerals of whatever description in the land." We cannot agree with plaintiffs in error's contention that the granting paragraph of the deed purports to convey only the surface estate and an undivided one-half interest in the minerals. It is r oppotiny 0 pt wl 3r�Publioatiol dots not „�sirP Me vimin non, ii ia) �u• z , it v ll be toisidered tar; rest be rA( r�, 'r; rile our opinion that the statement in the deed, that the land described is the same tract as that formerly owned by Talbot-Duhig Lumber Company and conveyed to Duhig by Talbot, is not intended to define or qualify the estate or interest conveyed but that it is inserted to further identify the tract or area described by metes and bounds. The deed, of course, does not actually convey what the grantor does not own. Richardson v. Levi, 67 Texas 359, 365, 3 S.W. 444. But the granting clause in this deed describes what is conveyed as the tract or parcel of land known as the Jordan Survey. This description includes Steve M. Dillard Wichita, KS the minerals, as well as the surface, and thus the granting clause purports to convey both the surface estate and all of the mineral estate. Holloway's Unknown Heirs v. Whatley, 133 Texas 608, 131 S.W. (2d) 89; Schlittler v. Smith, 128 Texas 628, 101 S.W. (2d) 543; Bibb v. Nolan, 6 S.W. (2d) 156 (application the grantee with title to the surface and a one-half [**880] interest in the minerals, excepting or withholding from the operation of the conveyance only the one-half interest theretofore reserved in the deed from Gilmer's estate to Duhig. It is the court's opinion, however, that the judgment of the Court of Civil Appeals should be affirmed by the application of a well settled principle of estoppel. The granting clause of the deed, as has been said, purports to convey to the grantee the land described, that is, the surface estate and all of the mineral estate. The covenant warrants the title to "the said premises." The last paragraph of the deed retains an undivided one-half interest in the minerals. Thus the deed is so written that the general warranty extends to the full fee simple title to the land except an undivided one-half interest in the minerals. The language used in the last paragraph of the deed is that "grantor retains an undivided one-half interest in the minerals." The word "retain" ordinarily means to hold or keep what one already owns. 54 C.J. p. 738; Words & Phrases, Second Series, Vol. 4, p. 371, Fourth Series, Vol. 3, p. 400; Webster's New International Dictionary. If controlling effect is given to the use of the word "retains," it follows that the deed for writ of error refused). Likewise the reserved to Duhig an undivided one- clause of general warranty has reference to "the said premises," meaning the land described in the granting clause, half interest in the minerals and that the grantee, Miller-Link Lumber Company, acquired by and through the deed only the surface estate. We assume that the and, but for the last paragraph of the deed retaining an undivided interest deed should be given this meaning. in the minerals, would warrant the title to the land including the surface estate and all of the minerals. When the deed is so interpreted, the warranty is breached at the very time of the execution and delivery of the deed, The writer believes that the judgment of the Court of Civil Appeals should be for the deed warrants the title to the surface estate and also to an undivided affirmed for substantially the same reasons one-half interest in the minerals. The result is that the grantor has breached as those set out in the opinion of that court, that is, that the language of the deed as a whole does not clearly and plainly disclose the intention of the his warranty, but that he has and holds interest in the minerals in addition to that previously reserved to Gilmer's in virtue of the deed containing the warranty the very interest, one-half of the minerals, required to remedy the breach. Such state of facts at once suggests the rule as to after-acquired title, which is thus stated in American estate, and that when resort is had to Jurisprudence: parties that there be reserved to the grantor Duhig an undivided one-half established rules of construction and facts taken into consideration which may properly be [*507] considered, it becomes apparent that the intention 24 of the parties to the deed was to invest "It is a general rule, supported by many authorities, that a deed purporting to convey a fee simple Landman / September/October 1996 or a lesser definite estate in land and containing covenants of general warranty of title or of ownership will operate to estop the grantor from asserting an after-acquired title or interest in the land, or the estate which the deed purports to convey, as against the grantee and those claiming under him." Vol. 19, suffered afterwards to acquire or assert a title and turn his grantee over to a suit upon his covenants for redress; the short and effectual method of redress is to deny him the liberty of setting up his afteracquired title as against his previous conveyance; that is merely refusing him the countenance and p. 614, Sec. 16. See also Robinson assistance of the courts in breaking v. Douthit, 64 Texas 101; Baldwin v. Root, 90 Texas 546, [*508] 40 S.W. had given." 3; Jacobs v. Robinson, 113 Texas 231, 254 S.W. 309; Caswell v. Llano Oil Company, 120 Texas 139, 36 S.W. (2d) 208; Moore v. Crawford, 130 U.S. 122, 32 L. Ed. 878. The case last cited quotes from a decision of the Michigan court the following clear statement of the rule and the reasons supporting it: "When one assumes, by his deed, to convey a title, and by any form of assurance obligates himself to protect the grantee in the enjoyment of that which the deed purports to give him, he will not be the assurance which his covenants of after-acquired title, it is, we believe, equally fair and effectual and also appropriate here. We recognize the rule that the covenant of general warranty does not enlarge the title conveyed and does not determine the character of the title. Richardson v. Levi, 67 Texas 359, 365-366, 3 S.W. 444; White v. Frank, 91 Texas 66, 70, 40 S.W. 962. The decision here made assumes, as has been stated, that Duhig by the In the instant case, Duhig did not acquire title to the one-half interest in the minerals after he executed the deed containing the general warranty, but he retained or reserved it in that deed. Plaintiffs in error, who claim under him, insist that they should be permitted to set up and maintain that title against the suit of defendant in error and to require it to seek redress in a suit for breach of the warranty. What the rule above quoted prohibits is the assertion of title in contradiction or breach of the warranty. If such enforcement of the warranty is a fair and effectual remedy in case deed reserved for himself a one-half interest in the minerals. The covenant is not construed as affecting or impairing the title so reserved. It operates as an estoppel denying to the grantor and those claiming under him the right to set up such title against the grantee and those who claim under it. For the foregoing reasons, the judgment of the Court of Civil Appeals is affirmed. Opinion adopted by the Supreme Court, Oct. 16, 1940. Rehearing overruled Dec. 18, 1940. Petroleum Corporation Anadarko Petroleum Corporation is one of the nation's largest independent oil and gas exploration and production companies. At year-end 1995, Anadarko had proved reserves equal to 3.16 Tcf of natural gas or 526 million barrels of oil. Anadarko is actively involved in exploration and develop ment drilling projects in North America and overseas in Algeria, Indonesia, Eritrea and Jordan; and is also pursuing additional opportunities elsewhere. AREA CONTACTS Reverdy H. Jones Land Supervisor North American Exploration ph: (713) 874 8832 fax: (713) 874 3571 Charlie Hughes Land Supervisor Offshore ph: (713) 874 8715 fax: (713) 874 8714 Glen McPhail Land Supervisor North American Development ph: (713) 874 8846 fax: (713) 874 1687 Anadarko Petroleum Corporation 17001 Northchase Houston, Texas 77060 ph: (713) 875 1101 Larry Brown Land Supervisor Unconventional Reservoirs ph: (713) 874 1624 fax: (713) 873 1389 :-tendman [September/October 1996 2 5