Treatment of American Indians 1850-1890

advertisement

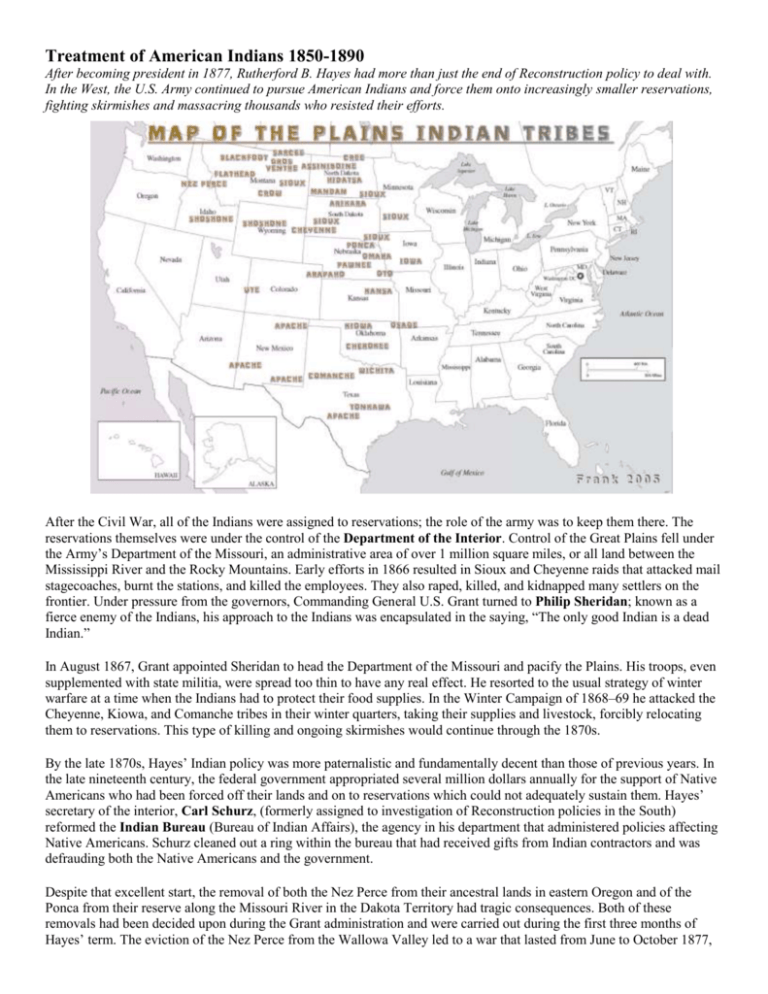

Treatment of American Indians 1850-1890 After becoming president in 1877, Rutherford B. Hayes had more than just the end of Reconstruction policy to deal with. In the West, the U.S. Army continued to pursue American Indians and force them onto increasingly smaller reservations, fighting skirmishes and massacring thousands who resisted their efforts. After the Civil War, all of the Indians were assigned to reservations; the role of the army was to keep them there. The reservations themselves were under the control of the Department of the Interior. Control of the Great Plains fell under the Army’s Department of the Missouri, an administrative area of over 1 million square miles, or all land between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains. Early efforts in 1866 resulted in Sioux and Cheyenne raids that attacked mail stagecoaches, burnt the stations, and killed the employees. They also raped, killed, and kidnapped many settlers on the frontier. Under pressure from the governors, Commanding General U.S. Grant turned to Philip Sheridan; known as a fierce enemy of the Indians, his approach to the Indians was encapsulated in the saying, “The only good Indian is a dead Indian.” In August 1867, Grant appointed Sheridan to head the Department of the Missouri and pacify the Plains. His troops, even supplemented with state militia, were spread too thin to have any real effect. He resorted to the usual strategy of winter warfare at a time when the Indians had to protect their food supplies. In the Winter Campaign of 1868–69 he attacked the Cheyenne, Kiowa, and Comanche tribes in their winter quarters, taking their supplies and livestock, forcibly relocating them to reservations. This type of killing and ongoing skirmishes would continue through the 1870s. By the late 1870s, Hayes’ Indian policy was more paternalistic and fundamentally decent than those of previous years. In the late nineteenth century, the federal government appropriated several million dollars annually for the support of Native Americans who had been forced off their lands and on to reservations which could not adequately sustain them. Hayes’ secretary of the interior, Carl Schurz, (formerly assigned to investigation of Reconstruction policies in the South) reformed the Indian Bureau (Bureau of Indian Affairs), the agency in his department that administered policies affecting Native Americans. Schurz cleaned out a ring within the bureau that had received gifts from Indian contractors and was defrauding both the Native Americans and the government. Despite that excellent start, the removal of both the Nez Perce from their ancestral lands in eastern Oregon and of the Ponca from their reserve along the Missouri River in the Dakota Territory had tragic consequences. Both of these removals had been decided upon during the Grant administration and were carried out during the first three months of Hayes’ term. The eviction of the Nez Perce from the Wallowa Valley led to a war that lasted from June to October 1877, during which time the Nez Perce under Chief Joseph out-maneuvered and out-fought the U.S. Army, headed by General Philip Sheridan. On a 1,700 mile retreat, the Indians were forced to surrender in Montana just south of the Canadian border. The surviving Nez Perce were sent to the Indian Territory (present day Oklahoma). The Ponca, who did not resist, were also sent to the Indian Territory and would have been forgotten had not one of their chiefs, Standing Bear, tried to return to Dakota on foot in the winter with the corpse of his son, in hope of burying him with his forebears. He was arrested in Nebraska but his plight aroused enormous sympathy in the Northeast and sparked an Indian-rights movement that opposed removals of Native Americans. Responding to pressure but also recognizing the injustice and the high cost of the removal policy, the Hayes administration abandoned it. Hayes, Schurz, and the Indian Rights Association were humane in their paternalism but were not interested in preserving the culture of Native Americans. Indeed, Hayes believed acculturation was the best policy; that education coupled with learning to be a farmer, herder, teamster, etc. was in the Indians’ best interest. Source: Thomas Nast for Harper’s Weekly, December 21, 1878. Article sources: http://millercenter.org/president/hayes/essays/biography/4 and http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Indian_Wars