Persily.Rosenberg.Minnesota.1.0

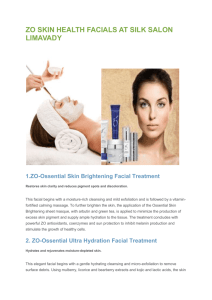

advertisement