The 2010 – Global Biodiversity Challenge meeting (21

advertisement

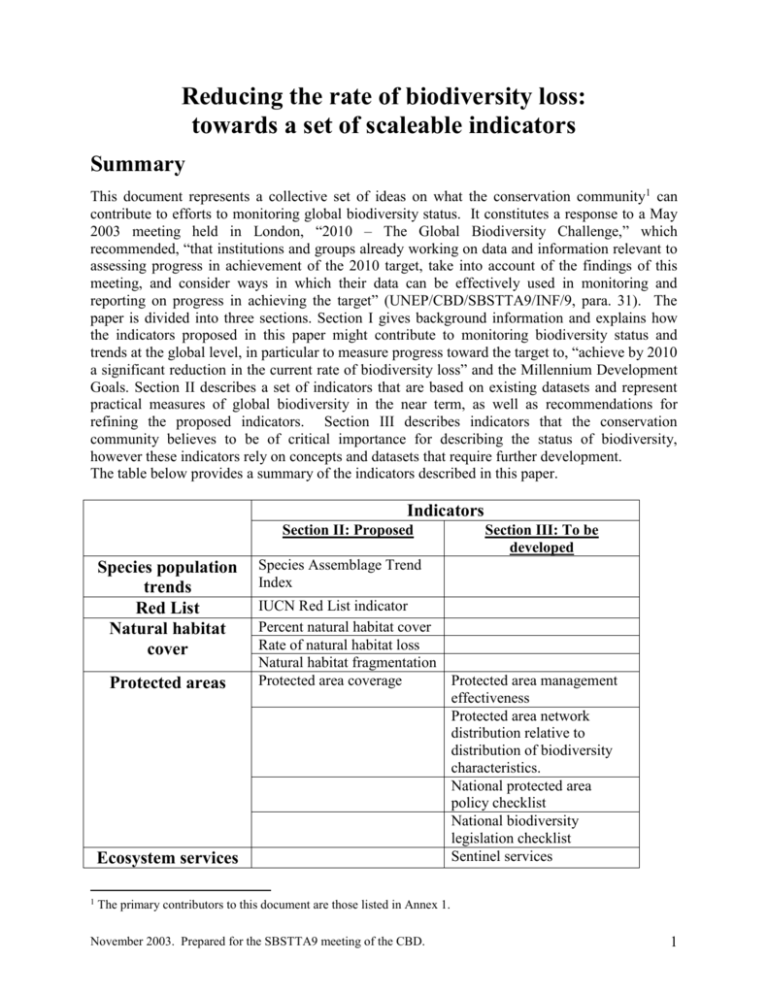

Reducing the rate of biodiversity loss: towards a set of scaleable indicators Summary This document represents a collective set of ideas on what the conservation community1 can contribute to efforts to monitoring global biodiversity status. It constitutes a response to a May 2003 meeting held in London, “2010 – The Global Biodiversity Challenge,” which recommended, “that institutions and groups already working on data and information relevant to assessing progress in achievement of the 2010 target, take into account of the findings of this meeting, and consider ways in which their data can be effectively used in monitoring and reporting on progress in achieving the target” (UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA9/INF/9, para. 31). The paper is divided into three sections. Section I gives background information and explains how the indicators proposed in this paper might contribute to monitoring biodiversity status and trends at the global level, in particular to measure progress toward the target to, “achieve by 2010 a significant reduction in the current rate of biodiversity loss” and the Millennium Development Goals. Section II describes a set of indicators that are based on existing datasets and represent practical measures of global biodiversity in the near term, as well as recommendations for refining the proposed indicators. Section III describes indicators that the conservation community believes to be of critical importance for describing the status of biodiversity, however these indicators rely on concepts and datasets that require further development. The table below provides a summary of the indicators described in this paper. Indicators Section II: Proposed Species population trends Red List Natural habitat cover Protected areas Ecosystem services 1 Section III: To be developed Species Assemblage Trend Index IUCN Red List indicator Percent natural habitat cover Rate of natural habitat loss Natural habitat fragmentation Protected area coverage Protected area management effectiveness Protected area network distribution relative to distribution of biodiversity characteristics. National protected area policy checklist National biodiversity legislation checklist Sentinel services The primary contributors to this document are those listed in Annex 1. November 2003. Prepared for the SBSTTA9 meeting of the CBD. 1 Each of the NGO contributors to this paper have developed indicators and monitoring frameworks and are working to build local capacity to collect data and report on biodiversity status. In addition, these NGOs are committed to working together and with governments, international organizations, academia, and other stakeholders to refine the proposed indicators and report in systematic fashion in the near term. Further, we are committed to helping define and implement a research agenda that will allow a greater number of consistent, reliable measures in the medium term. The community of organizations involved with the development of this paper respectfully contributes the following for consideration by the global community as a suite of scaleable indicators for measuring progress toward the 2010 target. I. Introduction In 2002, the world’s leaders, at the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD), set a target for ‘a significant reduction in the current rate of loss of biological diversity’ by the year 2010. This endorsed a previous decision by the Sixth Conference of Parties of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) (Strategic Plan, decision VI/26), restated in the Hague Ministerial Declaration of 14 April 2002. The WSSD recognized the ‘critical role’ of biodiversity in ‘overall sustainable development and poverty eradication’, and that ‘biodiversity is currently being lost at unprecedented rates due to human activities’ (WSSD Plan of Implementation 2002). Effective biodiversity conservation is thus fundamental to achieving the UN’s Millennium Development Goals (MDG) and in particular to ‘ensure environmental sustainability’ (MDG Goal 7) and to ‘reverse the loss of environmental resources’ (MDG Target 9). Is the world making progress in achieving these targets? Unfortunately, at present we cannot tell. This is because there is no systematic global framework for generating and interpreting data on the loss of biodiversity. A recent international meeting, 2010 – Global Biodiversity Challenge (21–23 May 2003), organized by the CBD, the United Nations Environment Programme – World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), included a working group which discussed measuring and reporting biodiversity loss at the international level (working group B). Discussions in this working group, and during the wider meeting, suggested that in order to inform decision makers and to track progress toward the 2010 target, a small set (fewer than 10) of high-level global indicators of biodiversity loss is needed. These global indicators should: o Meet three important criteria for effectiveness in the context of the 2010 target: 2 being scientifically credible, legitimate, and useful in meeting policy and decision-makers’ needs; o Provide at least three point measures between c. 1990 and 2010 to detect changes in rates; o Cover all three levels of biodiversity (genetic, species and ecosystems, including ecosystem function); o Include state, pressure, and response measures; 2 Outlined at the 2010 target meeting by Walt Reid, Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, who specifically mentioned indicators of extinction risk and population sizes in this context. November 2003. Prepared for the SBSTTA9 meeting of the CBD. 2 o o o Ultimately be part of the country reporting requirements; Be based largely on existing data Be low cost where possible. There is significant overlap between these criteria for global level biodiversity measures, and the criteria put forward for indicators at both global and national levels, including: Criteria for selection of indicators developed by the Expert Meeting on Indicators (UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA/9/10, para. 33; UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA/9/INF/7, para. 60); Criteria for selection of indicators noted by the meeting “2010 – The Global Biodiversity Challenge” (UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA/9/INF/9, para. 44) and in a document produced following the meeting that explores candidate indicators for the 2010 target (UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA/9/INF/26, para. 14); and Criteria for indicator selection arising from preliminary lessons learned from the Global Environment Facility Project on biodiversity indicators for national use (UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA/9/INF/19, pg. 4). More specifically, five categories of indicators were proposed by working group B at the 2010 target meeting to measure changes in the rate of biodiversity loss (species population trends, changes in natural habitat cover, Red List indicators, protected areas, ecosystem services). This paper describes indicators in each of these categories. The indicators described have a tendency to be terrestrially biased and marine and freshwater issues for monitoring global biodiversity status need to be further addressed by this group in the future. The meeting participants also recognized the important role played by conservation NGOs in facilitating data collection and monitoring biodiversity loss. Some appropriate data are already being collected globally, and with some refinement, these datasets could form the basis for at least some of the indicators that are required. Finally, it was recognized at the meeting that better co-ordination and collaboration among governments, international organizations, and NGOs is needed to implement an effective global biodiversity monitoring system. To articulate more clearly the potential contribution of NGOs, an informal NGO grouping3 at the meeting decided to describe a set of global measures that could be developed by integrating and enhancing ongoing work. This paper is a result of this concept, and subsequent discussions and input by a larger number of collaborators (see list in Annex 1 to this paper). Its purpose is not to provide a comprehensive list of indicators; rather, this paper is structured to highlight what the conservation NGO community can contribute to efforts to monitor global biodiversity. The indicators described in this paper are highly relevant to the CBD’s efforts to establish a framework for measuring progress toward achieving the target of ‘a significant reduction in the current rate of loss of biological diversity’ by the year 2010. The indicators described in section II are particularly important to measuring progress toward this target because they represent measures that are achievable in the near term, allowing sufficient measurements between a baseline year and 2010 changes in the rate of biodiversity loss. This emphasis on practicality is consistent with many of the documents before SBSTTA9 that emphasize the importance of using BirdLife International (Leon Bennun), The Nature Conservancy (Carter Roberts), The Zoological Society of London (Georgina Mace,), IUCN (Sue Mainka), WWF-UK (Jonathan Loh), and Conservation International (Elizabeth Kennedy, Rebecca Livermore and Simon Stuart) November 2003. Prepared for the SBSTTA9 meeting of the CBD. 3 available data and information systems to support indicator development and implementation, in order to deliver information to policy makers and other stakeholders in the near term (UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA/9/INF/9, paras. 45, 46; UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA/9/INF/26, paras. 4, 7). UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA/9/INF/27 provides useful background information on the potential role of existing international initiatives in reporting on the 2010 target. There is significant overlap between the indicators proposed in this document, those proposed by the Expert Meeting on indicators, and other indicators proposed in documentation for SBSTTA9. This overlap is demonstrated in a chart in Annex 2. The Open-Ended Intersessional Meeting on the Multi-Year Programme of Work (MYPOW) recommended that COP7 “establish specific targets and timeframes on progress toward the 2010 target” and “develop a framework for evaluation and progress, including indicators” (UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA/9/14, para. 6). This might be accomplished through a pilot phase between COP7 and COP8 to test a limited set of indicators for their suitability and feasibility, to be implemented by national institutes of the Parties and international organizations with relevant data and expertise. The indicators described in this document would be good candidates for such a pilot phase because of their practicality, their significant overlap with the large number of indicators proposed by the CBD Expert Meeting on Indicators and in other documents before SBSTTA9, and the substantial support for their implementation by the NGOs and other contributors to this paper. In addition, the indicators described in this paper will be useful for measuring progress toward achieving the MDGs. They are especially relevant to MDG Target 9, “reversing the loss of environmental resources,” and represent a refinement of the MDG indicators, “proportion of land area covered by forest” and “land area protected to maintain biological diversity.” Ecosystem services indicators in particular will help measure success in maintaining natural ecosystem functions necessary for achieving the MDGs goals and targets on poverty, hunger, and health. Consistency between the global biodiversity indicators used to measure progress towards the 2010 target and those integrated into the MDG framework is desirable for the practical reasons of data collection, reporting, and communication, but more importantly because such consistency will help facilitate the development of a clearer picture of some of the relationships between biodiversity and sustainable development. II. Proposed indicators for measuring biodiversity status based on existing datasets This section describes six indicators at the species to ecosystem scales for which conservation NGOs can immediately contribute data. Indicators for biodiversity at the genetic scale are not included in this paper. There is a terrestrial bias in the described indicators and additional work needs to be done to refine this set of measures in order to fully address marine and freshwater issues. Following brief descriptions, recommended actions for refining indicators are provided. Each indicator described below has individual strengths and weaknesses, but as a set they can provide a reliable picture of trends in global biodiversity, and are also useful at the national and site levels. Very importantly, the testing and refining of methods of data collection and analysis, and the generation of new data will greatly improve efficacy and rigor of these indicators, strengthening our ability to assess changes in the rate of biodiversity loss into the future. November 2003. Prepared for the SBSTTA9 meeting of the CBD. 4 A. Species population trends A wide range of organizations around the world monitor populations of particular species (mainly animals, especially commercially important species). Population trends across a set of species can be combined into a single index (sometimes called a ‘Species Assemblage Trend Index’, or SATI). Two existing examples are the Living Planet Index,4 the most recent of which uses data on 730 separate populations of species from forest, freshwater and marine ecosystems; and the Pan-European Common Birds Index (BirdLife International and European Bird Census Council) which combines counts across Europe of 24 farmland and 24 woodland bird species. Strengths Limitations A representative set of species can Good long-term population estimates provide a good indication of overall exist for only a relatively small set of environmental sustainability (e.g., species decline in common and widespread bird It is not easy to define a representative species in Europe with intensification set of species. Available population of land-use, and decline in stocks for trend data for species are biased many commercially important fish geographically (e.g., more monitoring species with over fishing) in developed countries), taxonomically Understandable (e.g., more monitoring of bird and High relevance to users mammals) and in other ways (focusing Data can often be collected relatively on, for example, commercially inexpensively by volunteers important, charismatic, common or threatened species). Further, it is difficult to incorporate very rare, low density or remote populations in population trend indices, further extending the potential for bias. Achieving fully representative coverage (both geographic and taxonomic) is difficult at best, and may be impractical. Populations fluctuate naturally (though including many species and long timeseries in the index helps to reduce this problem) Species Assemblage Trend Index This indicator uses species abundance data to measure species population trends. Using population time series data, a set of focal indices can be developed to track certain classes of species (e.g., commercially important or migratory species). Where desired, these indices might be aggregated to derive an overarching index that would ultimately be less sensitive to change than the individual targeted indices. Work is moving forward on amphibian, shark and other fish time series data in addition to the work on birds and the Living Planet Index. 4 Loh, J., et.al. (2000, 2001, 2002) Living Planet Report, WWF International November 2003. Prepared for the SBSTTA9 meeting of the CBD. 5 Data and indicator development needs: To produce a meaningful global indicator, careful consideration needs to be given to the species included and how their estimates are weighted. For example, by breaking the index down by region and by broad ecosystem type. In the future, extending population counts selectively to include a key set of ‘missing’ groups or habitats could refine the index. The selection of species for SATIs has substantial biases. Greater attention needs to be given to developing the data, expertise and organizations that can support inclusion of a broader taxonomic sampling into global biodiversity monitoring efforts. As we develop these global indices we have an opportunity to identify gaps in our ability to monitor biodiversity as well as articulate the need to fill these gaps on a global basis. B. Red List The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species is widely recognized as the world's most objective and authoritative listing of species that are globally at risk of extinction. Placing a species in one of the categories on the IUCN Red List involves a careful assessment of information against a set of objective, standard criteria. Over the last few years, the IUCN Red List has been developing into a global program to monitor the extent and rate of biodiversity degradation, both through documentation of risk of extinction for individual taxa as well as through development of indicators. The program is currently implemented by four partner organizations: the IUCN Species Survival Commission, BirdLife International, NatureServe and the Center for Applied Biodiversity Science (CABS) at Conservation International. Additional Partners are being recruited, in particular to provide plant expertise. The 2003 Red List (http://www.redlist.org/) includes assessments and re-assessments for more than 23,000 taxa of mammals, birds, most trees and others (including sharks, Asian freshwater turtles, mollusks, mosses, carnivorous plants and plants from several biodiversity ‘hotspots’) and will be available online as of 18 November 2003. A major global assessment of amphibians is nearing completion. A strategy is in place to assess a larger, more representative set of species with an emphasis on improving the balance of marine, freshwater and terrestrial species in the future. In addition to the individual taxa assessment process there are regular analyses of global trends undertaken at approximately four-year intervals to coincide with the World Conservation Congress. Strengths Easily understandable Based on authoritative assessments that are derived from recorded information on population and threat High relevance to the users Transparency of the assessment process (availability of documentation) Limitations Relatively long lag time Covers a small and unrepresentative set of taxa, and expanding the sample is costly Does not well reflect trends among ‘Least Concern’ species — those that are not yet immediately threatened A sub-group of the IUCN Red List Committee is working to develop a Red List indicator based on the Red List assessments, and the prototypes are now being tested on some well-documented taxa. This indicator will be based on two broad classes of data. One (non-sampled) is based on the Red List assessments of all taxa for groups, such as birds, in which all species have been assessed more than once. The strength of this indicator is that data for one group (birds) extends back to 1988. However, the number of completely assessed groups is currently limited: by 2010 November 2003. Prepared for the SBSTTA9 meeting of the CBD. 6 data will be available only for birds, mammals, and possibly amphibians. To address this taxonomic bias, the second (sampled) indicator is under development. This is based on a representative sample across all major taxa, stratified according to significant parameters such as broad biome, region, taxonomic group (e.g., phylum) and Red List category. This suite of species would be regularly reassessed, and overall changes in status could be taken to be representative of wider biodiversity. i. IUCN Red List indicator This IUCN Red List indicator uses the Red List data to measure the frequency with which species move across the threat categories. Changes in this indicator reflect step-wise changes in the numbers of species in the different categories; a species moving from Least Concern to Near Threatened contributes just as much to the changing score as a species moving from Endangered to Critically Endangered. Data and indicator development needs: We note that while the Red List Indicator process is moving rapidly the indicators are still in the development phase. For well-known species such as birds and mammals, much of the data is already available to implement the sampled and nonsampled data sets. Work is currently underway to make final decisions on Red List Indicator methodology such as rules for identifying genuine versus non-genuine changes in categories. For the sampled approach, the sampling strategy and species selection criteria are currently being developed. Gaps in the present data are being identified and strategies being developed to ensure that underrepresented groups receive greater coverage. C. Natural habitat cover Reduction and fragmentation of natural habitat cover may result in a reduction in ecosystem diversity and are directly related to the loss of species and ecosystem services. 5 Over time, changes in habitat cover can be measured by comparing satellite images and other remote sensing analyses, which are classified by habitat type (e.g. humid forest, savanna, etc.). This method makes it possible to generate at comparatively low cost a detailed picture of habitat change across large areas. Estimates of changes in forest cover are already being assessed globally by the Food and Agriculture Organization (Global Forest Resources Assessment 2000 6). Conservation International is developing habitat monitoring based on MODIS 7 and 30-m Landsat8 images for biodiversity hotspots and wilderness areas. Similarly WCS has conducted a 5 Human Development Report 2003, pg. 125, paragraph 2; Mooney and Cropper (Co-chairs). (2003). Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: A framework for Assessment. Island Press, Washington, DC. 6 FRA 2000 Assessing State and Change in Global Forest Cover: 2000 and Beyond. Forest Resources Assessment Programme. Working Paper 31. Rome: FAO. 7 MODIS (or Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) is a key instrument aboard the Terra (EOS AM) and Aqua (EOS PM) satellites. Terra's orbit around the Earth is timed so that it passes from north to south across the equator in the morning, while Aqua passes south to north over the equator in the afternoon. Terra MODIS and Aqua MODIS are viewing the entire Earth's surface every 1 to 2 days, acquiring data in 36 spectral bands, or groups of wavelengths (see http://modis.gsfc.nasa.gov/about/index.html). 8 Landsat 7 is a U.S. satellite used to acquire remotely sensed images of the Earth’s land surface and surrounding coastal regions. A recent anomaly of the satellite operation is presently being investigated. The Landsat 7 Project has received authorization to attempt recovery of the scan line corrector that failed on May 31, 2003 (see http://landsat.gsfc.nasa.gov/). November 2003. Prepared for the SBSTTA9 meeting of the CBD. 7 human footprint analysis9 and The Nature Conservancy has conducted land cover analyses for many regions and is embarking on a collaborative effort with other NGOs in assessing land cover status of major habitat types globally to help determine conservation status. Strengths Relatively inexpensive (as compared to establishing an on-the-ground survey method for determining habitat coverage) Understandable Coverage can be truly global Direct link to MDG indicator (proportion of land area covered by forest) High relevance to users Limitations At present, remotely sensed imagery can only be used reliably to differentiate a few land cover types. Need to expand land cover classification types and techniques, particularly for non-forest habitats Lack of standardized techniques for interpretation. Acquisition of quality remotely sensed imagery is problematic in some regions due to persistent cloud cover. Very difficult to apply to most aquatic systems (except coral reefs) Does not necessarily detect habitat degradation (not involving outright loss) A range of other measures can be calculated for specific sites where more detail is needed or useful. We propose the following indicators. i. Percent natural habitat cover indicator This indicator uses remotely sensed imagery to measure changes in habitat cover over time. For a defined habitat cover type, measuring the area for a described site will generate trend data for percent of natural habitat loss over time. This indicator can permit tracking remaining habitat area against a defined limit or threshold. ii. Rate of natural habitat loss indicator This indicator (a pressure indicator) can be calculated from the Percent Natural Habitat Cover Indicator and the rate of habitat loss at the site compared to present rate for similar or surrounding areas. Assessment of rates of change will signal if habitat loss is occurring more or less quickly over time, and can provide a relative comparison among regions. iii. Natural habitat fragmentation indicators We propose to measure patch size distribution and distance to edge distribution.10 These measures are useful in predicting the likely presence of associated area-sensitive or habitat specific species (e.g., forest obligates), the potential for species invasions, and the likelihood that ecological processes remain intact. WWF and WCMC measured forest fragmentation using Sanderson EW, Jaiteh M., Levy MA, Redford KH, Wannebo AV, and Woolmer G. (2002) “The Human Footprint and the Last of the Wild.” Bioscience 52 (10) 891-904. 10 A more complete set of fragmentation statistics can be developed and would include spatial indices of shape and size, proximity and isolation, connectivity, and diversity of classes of land cover types. 9 November 2003. Prepared for the SBSTTA9 meeting of the CBD. 8 global forest cover data c. 1990 which might serve as a rudimentary baseline for the fragmentation statistics (Living Planet Index, 1998). Data and indicator development needs: Across the different organizations involved, and especially for non-forest habitats, there is a need to establish standardized classification and interpretation techniques to ensure that data are comparable. The primary requirement is an agreed simple, standardized habitat classification system that can form a minimum description of habitat types (e.g., forests, savannahs, deserts, grasslands, freshwater, and coastal marine systems). Not all biomes are being monitored globally, especially marine and freshwater habitats. Further, we need improved techniques for characterizing fragmentation in each of the habitat types. Freshwater habitat fragmentation issues can be dealt with by tracking major watershed quality based on land cover coupled with information on dam and flow alterations. Coral bleaching events could be used as an indicator of reef condition. D. Protected areas Article 8(a) of the Convention on Biological Diversity enjoins parties to ‘establish a system of protected areas or areas where special measures need to be taken to conserve biological diversity'. IUCN defines a protected area as ‘An area of land and/or sea especially dedicated to the protection and maintenance of biological diversity, and of natural and associated cultural resources, and managed through legal or other effective means’.11 IUCN further recognises six classes of protected areas with management ranging from strict protection to sustainable use of natural ecosystems. A global list of protected areas in these six classes is maintained in the World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA) managed by IUCN and UNEP-WCMC and currently being re-structured and updated through the efforts of the WDPA consortium.12 Strengths Understandable Potentially global coverage Direct link to MDG indicator (land area protected to maintain biological diversity) High relevance to users Limitations An indicator based only on the total area designated, without measures of management effectiveness or the biogeographical context, may be misleading because the IUCN 1-6 categories are not hierarchical (see data and indicator development needs below) Depends on national authorities keeping the WDPA updated: at present, lags are often long The CBD definition of a protected area is, “a geographically defined area which is designated or regulated and managed to achieve specific conservation objectives” (Article 2). 12 BirdLife International (BI), Conservation International (CI), Fauna & Flora International (FFI), The Nature Conservancy (TNC), United Nations Environment Programme-World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEPWCMC), The World Resources Institute (WRI), Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and Conservation Biology Institute are active members of the WDPS consortium working to update and improve the quality and accessibility of protected areas data. 11 November 2003. Prepared for the SBSTTA9 meeting of the CBD. 9 i. Protected area coverage indicator Indicators to track protected area coverage should include actual area in hectares (overall and by IUCN category), and percent of total available habitat that falls under any protected area designation. Data and indicator development needs: Many concerns exist over the inconsistent quality and frequency of data reporting on protected areas worldwide. Further, the lack of management effectiveness measures associated with protected area information challenges the assumption that protection indeed exists for species, ecosystems, and major habitat types globally. The NGO community needs to work with government institutions and other partner organizations in providing timely and relevant data. Use of this information can also be improved, not only for tracking global targets, but also for adaptive management of protected area systems and sites. Further, private lands protection and other forms of conservation are increasingly contributing to biodiversity conservation targets and need to be integrated effectively into the WDPA. The consortium managing the WDPA should work to strengthen the existing database and expand its applicability to deliver data important to adaptive management at site, system and global scales. Additional information, for example, data on capacity or protected area funding, might also be integrated into the WDPA to better track resource needs for protected area strengthening. III. Recommended indicators to be developed While the proposed indicators represent what we think is a good start based on existing data and methods, additional indicators will be required in order to improve our understanding of biodiversity loss. A. Protected areas We acknowledge that the protected area coverage indicator must be complemented by measures of protected area management effectiveness and protected area distribution in relation to biodiversity features. To optimize conservation outcomes, designation of protected areas should be a response to the pressures on biodiversity, however this was not the case for most of the protected areas established prior to the 1970s. Using the results of a recent global gap analysis, 13 and assessing the total extent of protected areas (which can be broken down by region and habitat, and by IUCN class) thus could provide a straightforward response indicator for global biodiversity into the future. There are other important aspects of the response, however. These include management effectiveness (are sites really protecting biodiversity as intended?), a measure of how well protected area systems cover particular ecoregions (biogeographical units), and a measure of how well they incorporate ‘key biodiversity areas’ (sites that are internationally recognized for the important biodiversity they contain). A vast array of policies governing actions ranging from trade and economic development at the international level to fisheries quotas at the level of a community-managed reserve have significant implications for the status of biodiversity. Further response measures might come 13 Rodrigues, et.al. (2000) Global gap analysis: Towards a representative network of protected areas. Advances in Applied Biodiversity Science 5. Washington, DC, Conservation International. Full report can be downloaded from http://www.biodiversitysience.org/ (under Publications>In-house Publications>AABS) November 2003. Prepared for the SBSTTA9 meeting of the CBD. 10 from an evaluation of national policy frameworks for protected areas and more broadly for conservation. Thus we recommend four additional indicator types: management effectiveness, protected area network distribution relative to distribution of biodiversity characteristics, a national protected area policy checklist, and a national biodiversity legislation checklist. i. Management effectiveness indicators Methodologies for measuring management effectiveness have been proposed14 but are not yet widely agreed or used. There are ongoing discussions on how to establish global methods to monitor protected area management effectiveness. ii. Protected area network distribution relative to distribution of biodiversity characteristics Assuming the WDPA is updated and refined as planned, and governments continue to contribute the appropriate information, then tracking the total extent of Protected Areas designated (and their relationship to ecoregions and key biodiversity areas) should be achievable. For example, a recent global gap analysis15 provided an initial overview of the effectiveness of the worldwide network of protected areas in covering species in several major taxonomic groups and revealed that more than 1,000 species are not protected in any part of their range (with ~ 700 of those species threatened with extinction). We should build from this and similar analyses. Useful complimentary analyses might include underrepresented habitat types. iii. National protected area policy checklist As protected areas are the most well tested, and arguably the most effective, action for conserving biodiversity, we propose a National Protected Areas Policy Checklist as a tractable and representative measure of national level commitments to curbing biodiversity loss. This indicator is in the form of a “checklist” of steps that we believe are fundamental for the establishment and management of effective protected area systems. It complements the proposed indicators for measuring protected area coverage, management effectiveness, and placement with respect to biodiversity features. Possible questions to address in such a checklist include: o Is the protected area system representative of the diversity of ecosystems, communities, and species within the nation's boundaries? o Is it based on quantitative goals set for representing that biodiversity? o Does the protected area system represent the terrestrial, freshwater, and (if appropriate) marine biodiversity? o Where biomes, ecological systems, and species ranges cross national political boundaries, have governments cooperated in goal setting and collaborative conservation for these biodiversity elements? o Does the protected area system capture irreplaceable sites? 14 Stolton et al. 2002 for WWF and the World Bank and Hockings et al. 2000 for IUCN. Rodrigues, et.al. (2000) Global gap analysis: Towards a representative network of protected areas. Advances in Applied Biodiversity Science 5. Washington, DC, Conservation International. Full report can be downloaded from http://www.biodiversitysience.org/ (under Publications>In-house Publications>AABS) 15 November 2003. Prepared for the SBSTTA9 meeting of the CBD. 11 o Does the protected area system consider and include appropriate corridors and levels of connectivity for wide ranging species, and gene flow across the landscape? o Is a management effectiveness monitoring system in place to measure context, inputs, process, outputs, and outcomes? o Do protected area authorities have the final voice about all resource use, including permits for logging, mining etc? o Does the protected area system have a sustainable financing plan? o Has the protected area system been designed appropriately based on its socioeconomic context? o Has the protected area system been designed with local community and other stakeholder participation? This indicator should be informed by the proceedings of the World Parks Congress and the programme of work on protected areas to be established by governments at the Seventh Conference of the Parties to the CBD in February 2004. iv. National biodiversity legislation checklist It is widely accepted that particular regulatory and legislative frameworks are important in achieving biodiversity conservation. Thus, noting the presence (or absence) of key legislation or legislative tools that are in place nationally to support biodiversity conservation provides a useful measure of the status of enabling policy conditions. Recent analysis of 114 legislative tools 16 across 27 tropical high biodiversity countries resulted in the following list of 20 key laws or legislative tools that could potentially be used in a national biodiversity legislation indicator. i) ii) iii) iv) v) vi) vii) viii) ix) x) xi) xii) xiii) xiv) xv) xvi) xvii) xviii) xix) xx) 16 Classification of lands as protected areas and forest reserves Promotion of mechanisms for the creation of protected areas Development of a national system of protected areas Creation of protected areas of the maximum possible size Protected areas’ core area maximized Management plan required for any activity with negative impacts on biodiversity Adequate funding for park system, including enforcement activities, ensured Establishment of buffer zones around protected areas Only “certain” activities allowed within buffer zones Prohibition to set burns in forest terrains and surroundings Distance requirements to set up fires near forest areas Prohibition to introduce chemicals within forest domains or watercourses Obligation to use chemicals in an environmentally benign manner Prohibition to introduce / propagate nonnative species that damage wildlife Inclusion of biological corridors as a management category Creation of biological corridors to connect fragmented habitats Management plans, EIAs, and permit required for any forest exploitation Establishment of general criteria and principles on forest management Prohibition of deforestation and illegal exploitation Prohibition to exploit or fell any protected tree Asquith N. and C. Gascon (2003) personal communication. November 2003. Prepared for the SBSTTA9 meeting of the CBD. 12 B. Ecosystem services Ecosystem services are highly relevant to the Millennium Development Goals and their indicators. We recognize that the results of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment will help define a framework within which to develop indicators. We already have some proxies from the UNDP Human Development Index (e.g., availability of freshwater, catch per unit effort of fisheries). These indicators have the most obvious relevance to the persistence of life on earth for both human and non-human species. i. Sentinel services indicator Define sentinel services and establish a systematic method for aggregating datasets at the regional and global levels (e.g., a network of data providers). Some suggestions for services to include as part of this indicator are: o net primary production o sedimentation at major river mouths o water quality o net mining of soil nutrients o carbon storage o fisheries production o amount of water impounded o water stress index o volume and reliability of stream flow o pesticide application per kilometer squared o climate regulation o protection from storm damage (provided by reefs, seagrass beds, salt marshes, etc.) November 2003. Prepared for the SBSTTA9 meeting of the CBD. 13 Annex 1. List of contributing authors and reviewers Name Organization Jonathan Baillie London Institute of Zoology Andrew Balmford University of Cambridge Leon Bennun BirdLife Thomas Brooks CI Sara Christiansen WWF Sheldon Cohen TNC Randy Curtis TNC Gustavo Fonseca CI Marc Hockings IUCN Peter Herkenrath Birdlife Elizabeth Kennedy CI Ann Koontz EWW Rebecca Livermore CI Johnathan Loh WWF Georgina Mace London Institute of Zoology Susan Mainka IUCN Richard Margoluis Foundations of Success Brad Northrup TNC Sheila O'Connor WWF Jeffrey Parrish TNC John Pilgrim CI Kent Redford WCS Walter Reid Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Taylor Ricketts WWF Konrad Ritter TNC Carter Roberts TNC Nick Salafsky Foundations of Success Dan Salzar TNC Sanjayan Muttinglam TNC Marc Steininger CI Eleanor Sterling American Museum of Natural History Simon Stuart IUCN Harry Van der Linde AWF John Waugh IUCN Stacy Vynne CI David Wilkie WCS Email Jonathan.baillie@ioz.ac.uk apb12@hermes.com.ac.uk Leon.bennun@birdlife.org.uk t.brooks@conservation.org sarah.christiansen@wwfus.org scohen@tnc.org rcurtis@tnc.org g.fonseca@conservation.org m.hockings@mailbox.uq.edu.au Peter.herkenrath@bl.org.uk e.kennedy@conservation.org AnnKoontz@aol.com r.livermore@conservation.org jonathan@jloh.vispa.com georgina.Mace@ioz.ac.uk SAM@hq.iucn.org Richard@fosonline.org bnorthrup@tnc.org soconnor@wwfint.org jparrish@tnc.org j.pilgrim@conservation.org KHRedford@aol.com reid@millenniumassessment.org Taylor.Ricketts@WWFUS.ORG kritter@tnc.org croberts@tnc.org Nick@FOSonline.org d.salzar@tnc.org msanjayan@tnc.org m.steininger@conservation.org sterling@mail.amnh.org s.stuart@conservation.org hvanderlinde@awf.org jwaugh@iucnus.org s.vynne@conservation.org dwilkie@wcs.org We would also like to thank Jeremy Harrison, Ben ten Brink, and Robert Höft for their helpful comments. November 2003. Prepared for the SBSTTA9 meeting of the CBD. 14 Annex 2. Overlap between indicators proposed in this paper and those proposed in other SBSTTA9 documents. Indicator Indicator CBD category (italics = objective "to be developed" ) Pressure/ State/ Response/ Use Biodivers Aggre SBSTTA/9/14, ity Level gation "Integration of outcomeoriented targets…" POSSIBLE TARGETS and (POTENTIAL INDICATORS) SBSTTA/9/INF/26, "Proposed biodiversity indicators…" PROPOSED INDICATORS SBSTTA/9/10, National Level Monitoring and Indicators INDICATIVE LIST OF SUITABLE INDICATORS (single and composite) Species Species conservation + state Populatio Population sustainable use n Trends Trend Index species compo Rate of decline of particular trends in species Trends of set of species: (groups) site species reduced (2.1) abundance (2) representative of the (species assemblage indices, trends in community ecosystem, part of a particular living plant index) abundance (3-6) taxonomic group, exploited species assemblage species, endemic species, trend index (22) species of cultural interest, migratory species, waterfowl, etc. (p. 31) Species Assemblage Trend Indices (p. 34). Red List IUCN Red conservation List Indicator species state compo Rate of decline of particular trends in species Trends of set of Red List site species reduced; halt in the abundance: Red List Species (p. 31). increase in the number of (8) Red list indicators on species species at risk (2.1) (number Red List indicator groups (p. 34) of threatened species as (25) percentage of those assessed) November 2003. Prepared for the SBSTTA9 meeting of the CBD. Global Strategy for SBSTTA/9/10, National Level Monitoring Plant Conservation and Indicators (Decision VI/9) INDICATORS IN USE PER RESPONSE TARGETS TO CBD QUESTIONNAIRE (# of countries using indicator out of 52 responding Parties) A preliminary assessment of the conservation status of all known plant species, at national, regional and international levels (ii) No species of wild flora endangered by international trade (xi) Population growth and fluctuation trends of special interest species (23) Temporal change in number of species (increase/decrease) (21) Species with decreasing populations (25) Species with stable or increasing populations (20) Absolute and relative abundance, density, basal area, cover, of various species (27) Number of forest dependent species whose populations are declining (17) Population levels of representative species from diverse habitats monitored across their range (13) Changes in the distribution and abundance of native flora and fauna (17) Number of endemic/threatened/endangered/vulnerable species by group (31) Species threatened with extinction (number or percent) (28) Endemic species threatened with extinction (28) Species risk index (9) Number of extinct, endangered, threatened, vulnerable and endemic forest-dependent species by group (e.g. birds, mammals, vertebrates, invertebrates) (30) Threatened freshwater fish species as a percentage total freshwater fish species known (20) Threatened fish species as a percentage of total fish species known (17) 15 Annex 2. Overlap between indicators proposed in this paper and those proposed in other SBSTTA9 documents. Indicator Indicator CBD category (italics = objective "to be developed" ) Pressure/ State/ Response/ Use Biodivers Aggre SBSTTA/9/14, ity Level gation "Integration of outcomeoriented targets…" POSSIBLE TARGETS and (POTENTIAL INDICATORS) Natural Habitat Cover state Percent of conservation Natural Habitat Lost Rate of Natural Habitat Loss conservation + pressure sustainable use conservation Natural Habitat Fragmentat ion state SBSTTA/9/10, National Level Monitoring and Indicators INDICATIVE LIST OF SUITABLE INDICATORS (single and composite) Global Strategy for SBSTTA/9/10, National Level Monitoring Plant Conservation and Indicators (Decision VI/9) INDICATORS IN USE PER RESPONSE TARGETS TO CBD QUESTIONNAIRE (# of countries using indicator out of 52 responding Parties) ecosyste single Rate of natural habitats size of ecosystem m decreased (1.1) (forest type (1) cover; status of coral reefs; existence of other natural habitats; land-use change) Trends of set of structural variables which is representative of the ecosystem (p. 31). Annual conversion of selfgenerating area as % of remaining area: disturbance, habitat alteration (p.32). ecosyste single For selected areas of threats to m importance to biodiversity, biodiversity/single rate of loss and/or pressures (11) restoration (1.1) (forest cover; status of coral reefs; existence of other natural habitats; land-use change) Trends of set of structural variables which is representative of the ecosystem (p. 31). Annual conversion of selfgenerating area as % of remaining area: disturbance, habitat alteration (p.32). ecosyste single m Trends of set of structural variables which is representative of the ecosystem (p. 31).Annual conversion of self-generating area as % of remaining area: fragmentation (p.32). At least 10% of each Change in habitat boundaries (17) of the world's Changes in largest block of a particular habitat ecological regions type (10) effectively Total forest area (45) conserved (iv) Total forest area as a percentage of total land area (43) Percentage of forest cover by forest type (38) Forest area change by forest type (30) Change in land use, conversion of forest land to other land uses (deforestation rate) (27) Area and percentage of forest area affected by anthropogenic effects (logging, harvesting for subsistence) (27) Forest conversion affecting rare ecosystems by area (9) Change in habitat boundaries (17) Changes in largest block of a particular habitat type (10) Total forest area (45) Total forest area as a percentage of total land area (43) Percentage of forest cover by forest type (38) Forest area change by forest type (30) Change in land use, conversion of forest land to other land uses (deforestation rate) (27) Area and percentage of forest area affected by anthropogenic effects (logging, harvesting for subsistence) (27) Forest conversion affecting rare ecosystems by area (9) Fragmentation of forests (17) November 2003. Prepared for the SBSTTA9 meeting of the CBD. SBSTTA/9/INF/26, "Proposed biodiversity indicators…" PROPOSED INDICATORS 16 Annex 2. Overlap between indicators proposed in this paper and those proposed in other SBSTTA9 documents. Indicator Indicator CBD category (italics = objective "to be developed" ) Pressure/ State/ Response/ Use Biodivers Aggre SBSTTA/9/14, ity Level gation "Integration of outcomeoriented targets…" POSSIBLE TARGETS and (POTENTIAL INDICATORS) Protected Protected Area Area Coverage response ecosyste single Percent of the world's Response: protected m ecological regions areas (16) effectively conserved (1.2) (percent of each biome or ecoregion under protected areas; Inclusion of hotspots, Important Bird Areas, Important Plant areas etc; size/connectivity of protected areas) ecosyste compo Pathways for potential alien m site invasive species controlled; Management plans in place for at least 100 major alien species that threaten ecosystems, habitats or species (4.2) (Legal frameworks in place and status of implementation, numbers and descriptions of management plans) conservation Protected conservation + response sustainable use Area Manageme + benefit sharing nt Effectivenes s November 2003. Prepared for the SBSTTA9 meeting of the CBD. SBSTTA/9/INF/26, "Proposed biodiversity indicators…" PROPOSED INDICATORS SBSTTA/9/10, National Level Monitoring and Indicators INDICATIVE LIST OF SUITABLE INDICATORS (single and composite) Global Strategy for SBSTTA/9/10, National Level Monitoring Plant Conservation and Indicators (Decision VI/9) INDICATORS IN USE PER RESPONSE TARGETS TO CBD QUESTIONNAIRE (# of countries using indicator out of 52 responding Parties) At least 10% of each Total area of protected areas (use IUCN of the world's definition of protected areas) (38) ecological regions Size and distribution of protected areas (37) effectively Percentage of protected area of total forest area conserved (iv) (36) Percentage forest protected areas (by forest type, age, class, successional stage) (21) Number of protected areas Development of with management plan (p. 33). models with Effectiveness of area protocols for plant protection, effectiveness of site conservation and management (p. 34). sustainable use, based on research and practical experience (iii) Management plans in place for at least 100 major alien species that threaten plants, plant communities and associated habitats and ecosystems (x) 17 Annex 2. Overlap between indicators proposed in this paper and those proposed in other SBSTTA9 documents. Indicator Indicator CBD category (italics = objective "to be developed" ) Protected conservation Area Network Distribution Relative to Distribution of Biodiversity Characterist ics Ecosyste Sentinel m Services Services Pressure/ State/ Response/ Use Biodivers Aggre SBSTTA/9/14, ity Level gation "Integration of outcomeoriented targets…" POSSIBLE TARGETS and (POTENTIAL INDICATORS) response species + compo Percent of the world's ecosyste site ecological regions m effectively conserved (1.2) (percent of each biome or ecoregion under protected areas; Inclusion of hotspots, Important Bird Areas, Important Plant areas etc; size/connectivity of protected areas) Areas of particular importance to biodiversity protected (1.3) (Status of Important Bird Areas, Status of Important plant areas, Status of "hotspots") Percent of threatened species of suitably documented taxonomic groups conserved in situ (2.2) (percentage of threatened species conserved in situ by taxonomic group) ecosyste single Improved water quality of m seas and waterways (6.1) (water quality; eutrophication events; episodic events - fish kill, algal blooms etc; N deposition)Reduce greenhouse gas emissions according to targets set within the framework of UNFCCC [biological carbon sequestration] (6.2a) (GHG emissions)Maintain capacity of ecosystems to deliver goods and services (7) (production of food, fibre, including fisheries; flood control; protection against erosion) conservation + state/use sustainable use November 2003. Prepared for the SBSTTA9 meeting of the CBD. SBSTTA/9/INF/26, "Proposed biodiversity indicators…" PROPOSED INDICATORS SBSTTA/9/10, National Level Monitoring and Indicators INDICATIVE LIST OF SUITABLE INDICATORS (single and composite) Global Strategy for SBSTTA/9/10, National Level Monitoring Plant Conservation and Indicators (Decision VI/9) INDICATORS IN USE PER RESPONSE TARGETS TO CBD QUESTIONNAIRE (# of countries using indicator out of 52 responding Parties) At least 10% of each Size and distribution of protected areas (37) of the world's ecological regions effectively conserved (iv) Protection of 50% of the most important areas for plant diversity secured (v) 60% of the world's threatened [plant] species conserved in situ (vii) threats to biodiversity: acidification and eutrophication of terrestrial ecosystems, eutrophication and nitrogen load in rivers (13,14)services of biodiversity: carbon sequestration per ecosystem type, soil stability and suspended solids in rivers, river flow characteristics/flood s and drought (17,18, 20, 21) Estimate of carbon stored (18)Soil quality (31)Surface water quality (33)Ground water quality (30)Biological oxygen demand (BOD) on water bodies (eutrophication) (29)Stream sediment storage and load (14)Escherichia coli counts and nutrient levels as % of baseline levels (17)Lake levels and salinity (15) 18 Annex 2. Overlap between indicators proposed in this paper and those proposed in other SBSTTA9 documents. Indicator Indicator CBD category (italics = objective "to be developed" ) Biodivers National ity Policy Protected Area Checklist National Biodiversity Legislation Checklist Pressure/ State/ Response/ Use Biodivers Aggre SBSTTA/9/14, ity Level gation "Integration of outcomeoriented targets…" POSSIBLE TARGETS and (POTENTIAL INDICATORS) conservation + response sustainable use + benefit sharing -- compo Pathways for potential alien site invasive species controlled; Management plans in place for at least 100 major alien species that threaten ecosystems, habitats or species (4.2) (Legal frameworks in place and status of implementation, numbers and descriptions of management plans) conservation + response sustainable use + benefit sharing -- compo Pathways for potential alien site invasive species controlled; Management plans in place for at least 100 major alien species that threaten ecosystems, habitats or species (4.2) (Legal frameworks in place and status of implementation, numbers and descriptions of management plans) SBSTTA/9/INF/26, "Proposed biodiversity indicators…" PROPOSED INDICATORS SBSTTA/9/10, National Level Monitoring and Indicators INDICATIVE LIST OF SUITABLE INDICATORS (single and composite) Global Strategy for SBSTTA/9/10, National Level Monitoring Plant Conservation and Indicators (Decision VI/9) INDICATORS IN USE PER RESPONSE TARGETS TO CBD QUESTIONNAIRE (# of countries using indicator out of 52 responding Parties) NBSAP objectives met (p. 33). Development of models with protocols for plant conservation and sustainable use, based on research and practical experience (a.iii) Management plans in place for at least 100 major alien species that threaten plants, plant communities and associated habitats and ecosystems (x) NBSAP objectives met (p. 33). Development of models with protocols for plant conservation and sustainable use, based on research and practical experience (a.iii) Management plans in place for at least 100 major alien species that threaten plants, plant communities and associated habitats and ecosystems (x) No species of wild flora endangered by international trade (xi) Existence of the institutional capacity, policy and regulatory framework for the planning, management and conservation of biological diversity (28). *Chart does not specifically address Marine and Freshwater November 2003. Prepared for the SBSTTA9 meeting of the CBD. 19