1. Drink containers are about 50% of all roadside litter in Victoria.

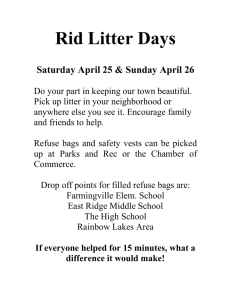

advertisement

A Community Based Investigation into Roadside Litter BY P & M COOK www.AFROCAB.org.au 1 Over the last 12 months we carried out 121 roadside litter surveys in Victoria and South Australia. We wanted to find out how many drink containers litter Victoria’s roadsides and whether there are as many along South Australia’s roadsides. In Victoria we counted 12,172 drink containers (not including flavoured milk cartons, tetra packs and all kinds of cups). There were 5,283 cans, 5,118 plastic bottles and 1,771 glass bottles. In South Australia they would be worth $608.60 to individuals, charities or community groups. In Victoria only the cans are worth money. At ninety cents a kilo (about one cent each) they would only be worth $52.83, through the ‘Cash a Can’ system. It is little wonder that no one bothered to pick up those cans and bottles, or any of the hundreds of thousands of other drink containers that we saw littering our roadsides. If Victoria brings in Container Deposit Legislation, the refund will need to be ten cents. Five cents does not hold the same value as it did when refunds began in South Australia, over 20 years ago. With a ten cent refund, those same drink containers mentioned above, would be worth $1,217.20. With that level of incentive, any cans and bottles would not stay on the ground for long. All sorts of people would pick them up, regardless of whether they are collecting them for themselves, for their family, a local community group or their favourite charity. Also, they would be doing their state, their country and our environment a good deed. Most importantly, a can and bottle refund system would make every day, Clean Up Australia Day. P & M Cook July 2006 Front Cover Photos From Left right Top: Mr Ted Barker of Hamilton who received the Lions Club Community Service Award for raising money for charity through collecting cans for 20 years or more. Below: Mr Ron Pankhurst & Mr Graham Eadie of the Emerald Clean Team. Centre: GLADE(Group for the Lilydale and District Environment) ‘Adopt a Highway’ group. Top: Mr Phil Hawkes of Werribee. He was Senior Citizen of the Year and received a Rotary award, for many years of cleaning up the Werribee River and roadsides. Below: Marg Stanton & Judy Stiff of Monbulk who clean roadsides and run a can cage for charity. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION ONE About this Report 1) Key Findings 2) Background 3) Aims 4) Methodology SECTION TWO 1) The Number of Drink Containers along Victoria’s Roads A Roadside litter surveys- Victoria B Community group surveys C ‘On foot’ roadside surveys 2) Drink Containers as a Proportion of the Total Roadside Litter A. Roadside litter surveys - Victoria B. Community group reports C. Roadside litter surveys – South Eastern South Australia 3) The Number of Drink Containers along South Australian Roads A.Rural highways B. Melbourne to Adelaide highway 4) The Composition of Drink Container Litter A. Victoria B. Community group reports 5) Further Evidence The National Litter Index 1 SECTION THREE 1) How big is This Problem? A. Comparing Production and Recycling Rates B. Why has Drink Containers Become a Big Problem? C. Beverage Litter Reform D. Victorian Litter Action Alliance E. Keep Australia Beautiful F. Vic Roads ‘Adopt a highway’ Scheme G. Public Place Recycling Bins H. Conclusion 2) What can be Done about This Problem? A. Financial Incentives Work B. Container Deposit Legislation C. Other Benefits that CDL Brings 3) Arguments Against CDL A. Drink Containers are a Small Percentage of all Litter B. It will Undermine Kerbside Recycling C. It Will Cost the Community too much 4) Recent Developments Appendix A Roadside Litter Survey Form B ‘Adopt a Highway’ Survey Form C List of Individuals and Community Groups Surveyed D About the Authors 2 SECTION ONE 1) Key Findings 1. Drink containers are about 50% of all roadside litter in Victoria. 2. A majority of the community groups surveyed, said that drink containers were a large or very large proportion of the litter that they collected. 3. Drink containers are a common litter item in other public areas like bike tracks, parks, walking tracks, car parks and railway stations. 4. Surveys done on foot found 170 drink containers per kilometre along Victoria’s rural roads and highways. 5. Surveys done from the car window showed 42 drink containers per kilometre on outer metropolitan roadsides and 21 per kilometre on rural roadsides. 6. There were many fewer drink containers along the roads we surveyed in South Eastern South Australia. 7. The Melbourne to Adelaide Highway has significantly more drink containers and other litter than other highways in South Australia. 8. Plastic drink bottles and aluminium cans are by far the most common drink containers. 9. The National Litter Index confirms that roadsides are the worst litter areas 10. The figures in the National Litter Index show that there are less drink containers as litter in South Australia, than in any other State. 11. The figures in the National Litter Index show that drink containers are the top litter item by volume and the third top litter item by number. 12. The most serious aspect of this problem is its cumulative effect. We know that every year billions more containers become litter or go to landfill and are not recycled. 3 SECTION ONE 2) Background I first became concerned about the number of cans and bottles littering our environment early in 2004, in my role as Environment Coordinator at a large secondary school. We collected over 4000 cans and bottles from the schoolyard per year. Despite this effort, many were still going to landfill via our rubbish bins while others were being washed down our drains and on into local creeks. This made me think, if our school has this many cans and bottles, how many must be littering the yards of all the schools in Victoria? I then started looking elsewhere to see whether cans and bottles were just a schoolyard problem. I quickly realised that drink containers in our schoolyard were just the tip of one very big iceberg. Drink containers were everywhere. You see them along bike tracks, in creeks, in parks, near shopping centres, railway stations and most of all you see large numbers of them along our roads. Since then I have read widely, written dozens of letters and organised several events in my area, to draw this problem to the attention of the wider community. From my letter writing to politicians and government officials, I found that my concerns were falling on deaf ears. From their responses, I could see that the advice they were being given, was that drink containers were just a small percentage of the litter stream and that it was not a significant problem in our environment. It was because of this that I decided to initiate this state wide survey of our roadsides and of the community groups who know the litter situation best. On trips around the state, my wife and I started counting drink containers and other roadside litter. The numbers amazed even us. The result was an even greater determination to bring this problem to the attention of government, in the hope that it would stir them into action. Peter Cook, July 2006 4 SECTION ONE 3) Aims The investigation aimed to: [1] Find out how many drink containers are on Victoria’s roadsides. [2] Establish what proportion drink containers are of all roadside litter. [3] Find out from community groups involved in regular clean ups of roadsides and other community areas, what proportion of the litter that they collect, is drink containers. [4] Find out whether there is less drink container litter in South Australia. [5] Analyse the figures in the National Litter Index to see if they confirm our findings. The question of how many drink containers litter our roadsides is important because in the past governments have not seen drink container litter as a major problem and therefore have not seen the need for alternative approaches to address this problem. The second question of what proportion drink containers are of all roadside litter is also important. This is because the incorrect notion that drink containers are only 10% of the litter stream, is a significant part of the justification for not introducing alternative approaches. Our surveying of community groups was very important to the first two questions because it enabled us to find out whether the results of the roadside surveys were consistent with the knowledge and experience of community groups that clean up their local areas. The question of whether there is less drink container litter in South Australia is critical because it answers the important question of whether Container Deposit Legislation would significantly reduce the amount of roadside litter in Victoria. The National Litter Index is the most comprehensive litter study of recent years that we know of. We thought it would be important to see if its figures support our findings. 5 SECTION ONE 4) Methodology Two methods were used to collect data on roadside litter. 1. COMMUNITY GROUP SURVEYS 60 community groups and individuals were surveyed. 38 of these groups are members of the Vic Roads ‘Adopt a Highway’ scheme. Because they do regular litter clean up work, we wanted to see if their experience of roadside litter confirmed what our roadside surveys showed. The other groups do clean up work around railway stations, shopping centres, parks and bushland areas. As a result, this report includes information about litter at various types of litter sites. 2. ROADSIDE SURVEYS Victoria Between August 2005 and June 2006, 109 surveys were done around Victoria. 75 of these surveys were done from the car window, while travelling at between 40-60 kph. A distance of 5 kilometres was surveyed in most instances. Sites were randomly chosen at intervals on our travels around Victoria. (See map) Most of the roads surveyed were highways or major roads in rural areas.18 surveys were done along outer metropolitan roads. (See map). 18 (16%) of the roadside surveys were done on foot over shorter distances of up to 500 metres. The purpose of these ‘on foot’ surveys was to check how accurate the car based surveys were. These ‘on foot’ surveys showed that there were always substantially more drink containers and other litter along roadsides, than what was seen from the car window. 15 surveys of non-roadside areas like bike tracks, railway stations and car parks, were done to provide a variety of sites. These were done on foot, which explains why so many drink containers were recorded in these areas. South Australia 27 roadside surveys were also conducted in South Australia in the same period. As in Victoria, sites were randomly chosen at intervals on our travels. The purpose of these surveys was to see if there were less drink containers along South Australian roads. Vic ‘’ Roadside from car ‘’ ‘’ ‘’ ‘’ Highways rural 31 ‘’ ‘’ Major roads rural 28 ‘’ ‘’ Outer metropolitan Melbourne 17 Roadside on foot Highways rural 8 ‘’ ‘’ ‘’ ‘’ Major roads rural 3 ‘’ ‘’ ‘’ ‘’ Outer metropolitan Melbourne 7 Vic SA ‘’ Other sites on foot Roadside from car ‘’ ‘’ ‘’ Bike tracks etc 15 Total Victoria 109 Highways rural 8 Major roads rural 19 Total South Australia 27 * For the purposes of this study, ‘drink containers’ comprise containers such as drink bottles, cans (aluminium, steel), flavoured milk cartons, tetra paks and cups (paper, plastic and polystyrene). 6 Outer Metropolitan Survey Sites Roadside Surveys from Car ‘Adopt a Highway’ & Other Community Clean up Groups Surveys on Foot Survey Sites in South Eastern South Australia Roadside Surveys from Car. *See Appendix for: List of Community Groups Surveyed Community Group Survey Form Roadside Survey Form 7 8 SECTION TWO 1) The Number of Drink Containers along Victoria’s Roads. SPECIAL NOTE: The figures throughout this study are for one side of the road only and therefore the actual number per kilometre length of roadside, could be doubled. A, 1. Our surveys revealed that there is a large number of drink containers along Victoria’s roads. We conducted 94 roadside litter surveys around Victoria, which gives an insight into the amount and type of litter along our roadsides. Our data shows that drink containers were most numerous on outer metropolitan roads [42 per kilometre], but were also numerous on major roads and highways in rural areas [21 per kilometre]. 2. We also found large numbers of drink containers in other public places. For example, around railway stations, in parks, along bike paths and walking tracks, etc. 50 Drink Containers per kilometre on Outer Metropolitan Roads, on Rural Major Roads and Highways and in Other Public Places 44 42 Containers per Km 0 21 Outer Metropolitan Roads Rural Highways & Major Roads Other Public Places B, Community Group Surveys We surveyed 60 community groups and individuals who do regular volunteer work cleaning up litter along roadsides and other community areas. We surveyed them because they have first hand knowledge and experience of litter. 38 of these groups are part of Vic Roads ‘Adopt a Highway’ scheme. 1. A majority of the 38 ‘Adopt a Highway’ groups reported that drink containers were a large or very large proportion of the roadside litter that they collected. Percentage Adopt a Highway Question 1 50 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 44.3 26.4 13.3 13.3 Small Medium 2.7 Very small Large Very large 9 The other 22 community groups and individuals, who regularly clean areas other than roadsides, were given the same survey form. 2. Community groups say that drink containers are a large or very large proportion of the litter they collect in other public places [other than roadsides]. Percentages "Others" Question 1 47.6 50 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 28.6 23.8 0 0 Very small Small Medium Large Very large C, ‘ON FOOT’ Roadside Surveys We conducted 18 on foot surveys, along highways and major roads in outer metropolitan and rural areas. These revealed much greater numbers of drink containers [170 per kilometre], than had been visible from a moving car. (Containers were often partly hidden in grass or drains or had been blown under bushes. Others were crushed or shredded by mowers and difficult to see in the grass.). 1. Surveys done on foot indicate that the number of drink containers along roadsides is actually much higher than car based surveys show. Drink Containers per Kilometre 250 200 170.8 150 100 50 21.3 0 On Foot Surveys Car Based Surveys 10 SECTION TWO 2) Drink Containers as a Proportion of Total Roadside Litter. A, Our 94 roadside surveys around Victoria focused on the amount and type of litter found. Surveys of major roads and highways in rural Victoria, showed that: 1. Drink Containers were 63% of all litter, along the roadsides surveyed in rural Victoria. Drink Containers and Non drink container Litter on Victoria's Rural Roads 5000 4349 Total Number 4000 3000 3332 2733 1785 2000 1000 0 Highways Non Drink Container Litter Major Roads Drink Containers B, We surveyed 60 community groups and individuals who do regular volunteer work, cleaning up litter along roadsides or in other public places. 38 of these were ‘Adopt a Highway’ groups, 15 were other community groups and 7 were individuals. 1. 95% of all the community groups and individuals surveyed, said that drink containers were a medium, large, or very large proportion of the litter that they collect. Drink Containers as a Proportion of Total Litter Medium 12 Small 5 Large 27 Very Small 1 Very Large 15 11 C, 27 roadside surveys were conducted in South Eastern South Australia. They focused on the amount and type of litter found along the roadsides there. 1. Drink containers are about one third of roadside litter in South Eastern South Australia. (This is because the Container Deposit Legislation in South Australia makes drink containers less numerous as litter items). 12 SECTION TWO 3) The Number of Drink Containers along South Australia’s Roads. We conducted 27 roadside surveys in South Eastern South Australia, both on highways and on major roads. As in Victoria, we surveyed one side of the road only. A. South Australian highways and major roads have significantly less drink containers, per kilometre, than highways and major roads in Victoria. B. In South Eastern South Australia, drink containers and other litter, along the Melbourne to Adelaide highway, were more per kilometre than on the other South Australian highways and major roads. The Number of Drink Containers per Kilometre along Highways and Major Roads 25 21.6 20.8 Number per Km 20 Highways 15 Major Roads 10 7.3 2.1 5 0 Victoria South Australia Drink Containers and Other Litter along Melbourne to Adelaide Highway in South Australia, c/f other Highways and Major Roads in South Eastern South Australia 30 28.3 25 Number per Km Drink Containers 20 Non Drink Container Litter 15 14.7 10 8.3 5 3.3 0 Melb –Adelaide Hwy Other Hwys & Major Roads 13 SECTION TWO 4) The Composition of Drink Container Litter A, Of 94 roadside surveys in Victoria and 27 in South Eastern South Australia, our surveys revealed that there are minor differences only, in the composition of drink container litter seen in the two states. 1. Plastic drink bottles and aluminium cans are the most numerous of all the drink containers found along Victorian and South Australian roads. 2. Glass bottles, per kilometre, are much less in South Australia than in Victoria. 3. Cardboard, foam and plastic cups are more numerous along highways than other roads, especially outside major towns that have fast food outlets, in both States. 4. Cardboard cartons [flavoured milk], are slightly more, per kilometre, on highways in South Australia, than on highways in Victoria. The Compositiion and Number of Drink Containers, per kilometre, on Highways and Major Roads in SE South Australia 3.6 4 Number of Containers 3.5 3 2.5 2.5 1.7 2 1.5 1.4 0.5 1 0.5 0 Aluminium Cans Plastic Bottles Glass Bottles Cardboard Cartons Cups 14 B, COMMUNITY GROUP SURVEYS We surveyed 60 community groups [38 Vic Roads ‘Adopt a Highway’ groups, 15 other community groups and 7 individuals] who clean either roadsides or other public areas in Victoria. In those surveys we asked which type of drink containers/beverage containers were most commonly found during their clean ups. 1. The community group surveys showed that plastic bottles and aluminium cans were the most numerous drink containers. 2. The community group surveys showed that glass bottles were also a significant percentage. [This reflects the fact that glass bottles often accumulate out of sight in drains or in long grass, until an area is cleaned by hand]. Responses of 'Adopt a Highway' Groups 35 31.6 27.4 Percentages 30 25 18.9 20 15 10.6 11.5 10 5 0 Plastic Bottles Aluminium Cans Glass Bottles Flavoured Milk Cartons Cups Responses of Other Community Groups and Individuals 36.4 40 35 31.8 29.6 Percentages 30 25 20 15 10 2.2 5 0 0 Plastic Bottles Aluminium Cans Glass Bottles Flavoured Milk Cartons Cups 15 SECTION TWO 5) Further Evidence The National Litter Index In early 2006 Keep Australia Beautiful published the ‘National Litter Index’. This is a very extensive litter survey, conducted across five states. (The Tasmanian figures are published separately). 1. The National Litter Index identified that roadside litter is a major problem. Its data shows that 48% of all litter, by volume, was on highways, even when only 18% of its survey sites were on highways. 2. Figures from the National litter Index also show that drink containers are a major litter item along roadways and in other public places. (See page 18) 3. Also, using the figures from the National Litter Index, drink containers, when counted together as the one litter type, are actually the worst litter item by volume and the third worst by number, across all the 5 states that were surveyed. The following graphs use the figures from the National Litter Index. Top 10 Litter Items by Volume (m3) 1. Drink 0.678 0.227 0.571 Containers 0.636 2.Illegal Dum ping 1. 0 4 2 0 . 9 12 0.475 0.456 0 . 12 0.48 1. 2 0.072 0.23 0.291 0 . 15 8 0.208 0.3 0 . 19 1 3.Containers, dom estic type 4.Containers, industrial e.g. oil 0 . 13 5 0 . 112 0 . 14 8 0 . 15 2 0 . 14 9 0 . 16 0 . 15 0 . 12 6 5.Cups/take aw ay containers(paper) 6. New spapers& m agazines 7.Cigarette packets 0.1 0.039 0.044 0 . 113 0.097 0.048 0.057 0.049 0.037 0.057 0.043 8.Cups/take aw ay containers(plastic) 0.034 0.037 0.029 0.041 0.03 0.036 9. Construction m aterials 0.031 0.06 0.033 0.021 0 . 0 19 0.022 10. Foil take aw ay 0.225 0 . 13 5 0.207 0.292 0.449 Average SA WA VIC NSW QLD 0 . 0 19 0.024 0.006 0 . 0 11 0.036 0 . 0 18 (Drink containers do not feature prominently in the National Litter Index report. Metal bottle tops, can ring pulls, plastic bottle tops and paper cups are the only items of drink litter that appear in the index’s list of top ten (worst) litter items. This is because drink containers are divided up into 38 separate categories, according to their contents. Aluminium cans are divided up into 5 different categories, plastic drink bottles into 12 different categories, glass drink bottles into 14 categories and cardboard cartons into 7 categories. This has the effect of making each individual category of drink container, seem less numerous than other litter items.) 16 4. Another important fact revealed by the data in the National Litter Index, is that drink containers are less numerous in South Australia, than in the other states. Top 10 Number of Litter Items 512 0 54 8 2 Cigarette butts 719 7 6 8 14 6 76 0 13 4 1 152 9 12 2 0 12 57 13 4 6 13 51 Other paper (including tissues) 50 3 Drink Containers All other plastic 6 2 75 10 3 8 16 3 6 10 15 1159 8 76 Average 640 10 6 4 6 16 50 0 333 687 Snack bags and confectionery w rappers (plastic) WA 6 13 774 632 56 7 362 72 9 Metal bottle tops and can ring pulls 291 3 16 346 2 74 244 2 74 Plastic bottle tops 2 59 348 224 201 285 239 SA VIC c NSW QLD 2 57 243 205 238 296 304 Straw s Cigarette packets 223 261 227 170 261 19 7 207 2 19 248 13 3 118 3 16 Other Foil Drink Container Volumes per State 1.2 1.042 0.912 1 0.8 0.636 0.678 0.571 0.6 0.4 0.227 0.2 0 SA QLD VIC Average NSW WA 17 The following graph, using figures in the National Litter Index and according to our analysis, shows the volumes of Drink Containers and of All Other Litter, that were found in the various sites in Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia. The volume of Illegal Dumping is shown separately because it is a different kind of littering. It is large in volume, its contents have not been recorded and to include it with All Other Litter exaggerates that figure. When not including Illegal Dumping, in Victoria drink containers are 37.3% of all litter on Highways, in South Australia drink containers are 29.3% of all litter on Highways and in Western Australia drink containers are 60.6% of all litter on Highways. In Recreational Parks drink containers in Victoria are 80.1% of all litter. ’’ ’’ ’’ ’’ ‘’ ’’ South Australia are 13% of all litter. ‘’ ‘’ ‘’ ‘’ ‘’ ’’ Western Australia are 46.4% of all litter According to the National Litter Index figures, in Victoria drink containers are 29.7% of the volume of all litter statewide, in Western Australia drink containers are 55.2% of the volume of all litter statewide and in South Australia drink containers are 21.8% of the volume of all litter statewide, when not including illegal dumping. 18 SECTION THREE 1) HOW BIG IS THIS PROBLEM? A. Comparing Production Rates and Recycling Rates The size of the problem can be quantified by comparing production rates with recycling rates: 1) PET (polyethylene terephthalate) Plastic Bottles Australia produces 2.2 billion PET bottles every year. At best, only 35% are recycled. This means that every year in Australia at least 1.6 billion PET bottles disappear. They go to landfill and they litter our roadsides and waterways. 2) Aluminium cans We recycle 65% of the 3 billion aluminium cans produced in Australia every year. As a result, about 1 billion cans are not being recycled. They also disappear into landfill and roadsides and waterways. This is a cumulative problem. Every year billions more plastic, glass, aluminium and other types of containers are being added to those already accumulated. B. Why have Drink Containers Become a big Problem? This has been a problem in Australia for many years because opposition from industry has limited beverage litter reform and prevented the introduction of measures which specifically target drink containers. The problem has worsened in recent years because of a steady increase in away from home beverage consumption and a simultaneous increase in the production and sales of single use, disposable containers. C. Beverage Litter Reform The history of beverage litter reform in Victoria is essentially the history of (a) industry opposition to the introduction of Container Deposit Legislation (CDL) and (b) conflicts of interest which have inhibited key stakeholders in this debate. In recent years industry has used a number of arguments and strategies in their fight against CDL. Their main arguments are covered in the section on ‘Arguments against CDL’. One of their main strategies has been to shift the blame for beverage litter from themselves to consumers. By sponsoring anti litter campaigns, which tell people not to litter, the community has been getting a clear message that it is people who are to blame for litter, not the companies that produce and use cheap throw away containers. Another strategy is to shift attention away from cans and bottles, to other litter such as cigarette butts. The beverage industry has also put money into public place recycling. Their reason for doing this is evident in the following quote. On the ABC’s 7.30 Report, Alec Wagstaff of Coca-Cola Amatil said, “by proposing solutions like public place recycling and putting up money for these programs, we think industry is doing its fair share”. By sponsoring things like anti litter campaigns and public place recycling bins, industry creates the impression that it is doing the right thing. This helps hide the fact that they vigorously oppose more effective litter reforms. In the process, they perpetuate the damage that their products are doing. Conflicts of interest also help explain the lack of reform. One example is an organisation whose purpose is to keep Australia beautiful. It opposes CDL using the same arguments as one of its major sponsors, the Beverage Industry Environment Council. It also produces litter surveys, the data from which is presented in such a way, that the products of the beverage industry almost disappear as litter items. 19 Secondly, we have a peak litter body with a membership which includes several large commercial organisations which have a history of opposition to CDL. How can such an organisation arrive at best practice policies, when some of those policies are perceived to be contrary to the commercial interests of a number of its members? In this situation, the only ‘action’ we have seen with beverage litter is the continuation of the status quo. The best chance for reform will come when industry decides it wants to be seen as part of the solution rather than as a major part of the problem. Until then, their opposition to CDL will increasingly be seen as the main reason why we have drink containers littering our community. D. The Victorian Litter Action Alliance (VLAA) According to its website the VLAA “is the peak litter management and prevention organisation in Victoria”. It “was established in April 2000 to coordinate the efforts of organisations across the state to combat the problem of litter”. A ‘best practice approach’ is stated as a major focus of this organisation. Another related focus, which features prominently on its website, is data collection, which it says “is used to develop policy and programs about litter prevention”. Data it suggests is important because it can be used to answer the question “Why do people litter and what would stop them?” The VLAA and its member organisations conduct fairly complex data collection exercises, to monitor litter and littering behaviour. In the case of drink containers, expensive data collection exercises are not necessary to find out what would stop some people littering and what would motivate others to pick up the containers that others have littered! It is well known from South Australia and countries which have can and bottle refund systems, that Container Deposit Legislation (CDL) is the answer to this problem. The proof can be seen in the much higher recycling rates in South Australia. CDL, however, is unlikely to be endorsed as part of a Victorian Litter Action Alliance best practice approach. The Beverage Industry Environment Council (BIEC), one of its 13 member organisations, has long been steadfastly opposed to Container Deposit Legislation. Also, BIEC is important to the Litter Action Alliance data collection. According to the website, BIEC funds its Litter Behaviour Studies and the Disposal Behaviour Index. The data collection studies talked about on the VLAA website, identify some improvements in ‘desirable disposal behaviour’. However, the question is; Can Victoria’s environment wait for gradual incremental improvements in littering behaviour over a number of years, given the enormous numbers of drink containers that are accumulating every year? According to the VLAA website, they do not place a lot of value on litter counts because they say “they provide only limited information about attitudes, behaviour, the type of infrastructure present at a site and what is going on in the environment”. The figures in our report, we believe, say a lot about behaviour and the consequences of that behaviour for our environment. Based on this, we think it is time that the government and the Victorian Litter Action Alliance took some real action on drink container litter. When deciding what to do, they should note this May 2006 comment from New York State Attorney General, Eliot Spitzer. He said, “the Bottle Bill (refund system) is the single most effective recycling and anti-litter law that we have”. E. Keep Australia Beautiful Victoria (KABV) KABV is one of the 13 members of the Victorian Litter Action Alliance. Its programs, like ‘Tidy Towns’ and more recently ‘Stationeers’, have been a significant part of volunteer litter programs in Victoria. The National Litter Index published by KAB (see page 16), shows that 48% of all litter (by volume), is on roadsides. Its figures also show that drink containers are the number 1 litter item at the top of the 10 worst litter items (by volume). 20 Knowing this, it is disappointing that Keep Australia Beautiful Victoria, actually opposes having Container Deposit Legislation - the only proven method of controlling beverage litter. KABV, (like one of its sponsors here in Victoria - the Beverage Industry Environment Council), uses concerns about the effect of CDL on our kerbside recycling system, as its reason for opposing CDL. Several reports have been written on this issue, with varying conclusions. KABV should consider the fact that CDL and kerbside operate successfully, side by side, in South Australia. F. Vic Roads ‘Adopt A Highway’ Scheme Another focus of the current approach is the ‘Adopt a Highway’ scheme. These volunteers do great work cleaning the approaches to their towns. Unfortunately, the litter keeps coming back, indicating that behaviour has not changed. Programs like ‘Adopt a Highway’ are just a bandaid. A much more proactive approach is needed, which gives people a genuine incentive to either not drop drink containers, or for others to pick them up. Some of the ‘Adopt a highway’ groups that we surveyed, suggested there was a shortage of roadside bins and that existing bins are sometimes full to overflowing. Unfortunately, councils who would have to finance a roll out of new bins and then have to pay to have them emptied, may not favour this option. Even if more bins did reduce the problem, it would send the wrong message to people. Drink containers are made from non renewable resources. Theycshould go into recycling bins not rubbish bins. Councils should not encourage people to put them in rubbish bins. They belong in the recycling stream. For many years government policy has aimed to reduce the amount of recyclables going to landfill. Increased provision of rubbish bins along highways and major roads would directly contradict this policy. G. Public Place Recycling Bins Perhaps because of sustained pressure for action on drink containers, some people in industry have said there should be more public place recycling bins. However, this would only be appropriate to cities, provincial centres and major towns. It would not address the roadside problem, especially in rural areas. More importantly, trials of public place recycling have shown that while it works quite well for special events, contamination of bin contents in other settings is high, resulting in a significant proportion of the recyclables in these bins, still going to landfill. For both these reasons, public place recycling is not a solution to this problem and does not remove the need for action on drink containers. H. Conclusion Current approaches to roadside litter focus mainly on anti litter media campaigns and on fines. If this approach was working, we would not have the problem with drink container litter that this report has highlighted. Clearly more of the same is not the solution. Bendigo Creek Linear Park Trail 30/4/06 21 SECTION THREE 2) WHAT CAN BE DONE ABOUT THIS PROBLEM? A. Financial Incentives Work Many people think the solution to this problem is a can and bottle refund system like in South Australia. They say this because they remember how kids used to make pocket money from collecting glass soft drink bottles in the 1960’s. Others having lived or travelled in South Australia have seen the difference that it makes there. All see it as a logical and common sense system that works. It works because it gives people an incentive ‘to do the right thing’. Evidence of this can be seen in the Australian recycling statistics. The recycling rate for aluminium cans (65%) is much higher than the 35% rate for PET plastic bottles. The difference is because of the ‘Cash a Can’ program. (This is where people take cans to a metal merchant to receive about 90 cents per kilo, i.e. about 1 cent per can). Even such a small financial incentive increases the recycling of aluminium cans. The financial incentive is why 72% of PET bottles and 80% of aluminium cans are recycled in South Australia, where there is the 5 cent refund on these items. (Our study shows that where there are refunds, there is also less littering of the refund containers.) B. Container Deposit Legislation The term ‘Container Deposit Legislation’ (CDL) is commonly used when referring to a refund system for drink containers. The system used in South Australia is one of several CDL models used around the world. The fact that it works in South Australia is clear, not only from our report, but from the much higher recycling figures for drink containers in South Australia and from how much less drink container litter is collected in South Australia on Clean up Australia Day. Speaking about this, Chairman, Ian Kiernan said on ABC’s 4 Corners “We’ve got 50% less collection of beverage containers on Clean up Australia Day in South Australia than other states”. Overseas evidence is not difficult to find. In 2002, Eliot Spitzer, the Attorney General of New York State said, “Our 20 year old bottle Bill (CDL) has been a phenomenal success at keeping millions of containers out of our landfills and off our streets in the form of beverage litter”. The merits of CDL go beyond reducing litter. Its other benefits outlined below, should be considered when investigating its introduction in Victoria. C. Other Benefits that CDL Brings Social and Community Benefits In South Australia individuals, charities and community groups are major beneficiaries of their refund system. For example, scout groups descend on football grounds after a match, to collect the discarded drink containers which are cashed, to subsidise their activities. Many individuals collect drink containers and donate the proceeds to charities. As John Phillips, Director of Keep South Australia Beautiful said, on the ABC’s 4 Corners program ‘The Waste Club,’ “There’s a lot of people in South Australia making hundreds of dollars a week on other people’s litter”. Putting money back into the community is another very positive feature of South Australia’s deposit / refund system. It is one of the reasons why their refund system has such a very high public approval rating. 22 Environmental Benefits The Victorian government places much importance on sustainability. Consistent with that, our problem with drink container litter must be rectified. The current situation is clearly unsustainable, in terms of our use of finite landfill space, use of non renewable resources and the impact of drink container litter on our environment, especially our waterways. It is well known that making new containers from virgin materials, requires more energy and water than what is required to make those same containers using part recycled content. The Victorian government’s Greenhouse strategy is good. Unfortunately this government’s position on CDL, contradicts its Greenhouse strategy. It ensures that much more energy will be used in producing drink containers in the future. Benefits to Tourism A major problem of drink containers as litter, is that they are large, they are conspicuous and they accumulate. They cannot be helping our tourism industry, especially when we are trying to promote Australia’s natural beauty. The benefits that flow to tourism from low litter levels are reflected in this 1996 comment from Angus King, Governor of Maine USA. He said, “As a tourist oriented state whose major attraction is its natural beauty, we are very aware of the contribution of the deposit system in keeping our roadsides clean”. Benefits to Industry It is good public relations for companies to be seen to support measures which tackle visible environmental problems. For this reason it would be in the long term interests of the beverage and packaging industry to support the introduction of CDL. It would be better for them to be seen as part of the solution to this problem rather than increasingly being seen as a major reason why we continue to have this problem. . Caravan Parks in South Australia find it worthwhile to provide recyclihg bins for CDL containers. 23 SECTION THREE 3) ARGUMENTS AGAINST CDL The opponents of deposit systems are mainly in the waste, beverage and packaging industries. Their most common arguments against CDL are the following: A. Drink Containers are a Small Percentage of All Litter This fiction is used as a justification for a ‘do nothing’ approach. Drink containers are truly a small percentage of the litter stream only where you have container deposit legislation, as in South Australia. Drink containers becoming a small percentage of the litter stream is a reason for having CDL, rather than a reason for opposing it. The Beverage Industry Environment Council says drink containers are only 10% of the litter stream. Our roadside surveys, the Community Group surveys and the figures in the National Litter Index, all show that drink containers are actually a large part of the total litter stream. B. It Will Undermine Kerbside Recycling The second argument used against CDL is that it will take many of the high value recyclables out of our kerbside system and therefore possibly undermine its financial viability. Two reports supporting the above concerns were the 2000 C4ES report on the ‘Impact of CDL on New South Wales recycling and litter Management Programs’ and the 2002 Nolan ITU report on the financial impact of CDL on three Victorian communities. In the same period there were two other reports which touched on this question. In 2000 a consultancy report was prepared for the South Australian EPA entitled, “Container Deposit Legislation: Economic and Environmental Impacts”. It concluded that it was “difficult to accept the argument that CDL adds significant net cost to the kerbside recovery system of local government”. It also said “that of the councils interviewed, none saw CDL as having a major deleterious effect on kerbside recycling programs”. Also, in 2002 the Institute for Sustainable Futures released its “Independent Review of Container Deposit Legislation in New South Wales” which proposed a CDL system working parallel to its existing kerbside system. In the absence of a definitive answer to this question, it seems logical to look at the situation in South Australia where CDL and kerbside operate successfully side by side. The fact that CDL does take cans and bottles out of kerbside is not seen as a problem in South Australia. When asked about this a local government waste management officer in South Australia told us it was not a concern to them because their kerbside system was still achieving its primary objective of substantially reducing the amount of recyclable materials going to landfill. In the absence of hard evidence that CDL and kerbside are not compatible, it could be said that this argument is a distraction from the more important question of whether, by itself, kerbside is enough for society to achieve its goals of minimising waste to sustainable levels. By itself, kerbside has one major problem. It is out of step with consumption patterns. At present 50% of beverages are consumed away from the home and away from kerbside recycling opportunities. This is a major reason why the majority of drink cans and bottles still either go to landfill or end up as litter. As a result, CDL is needed to fill this gap. It is a parallel system which complements kerbside recycling rather than competing with it. In reality, the biggest threat to the long term viability of kerbside is not CDL. It is the reluctance of industry to make a reasonable contribution to the cost of running kerbside. 24 Industry makes and profits from most of the packaging recycled through the kerbside system. For this reason the cost of running kerbside should not fall almost totally on ratepayers and councils. This is an unsustainable burden that must be rectified. Consistent with their concern that CDL might undermine kerbside, industry should contribute a significant percentage of the ongoing costs of running kerbside, to ensure its long term viability. C. It will Cost the Community Too Much This conclusion is based on the 2002 Nolan ITU study conducted for EPA Victoria. This study has two main problems due to the very narrow terms of reference. A) It only looked at one CDL model called ‘return to point of sale’. This is not the South Australian model, plus it is the least practicable and most expensive CDL model. B) This study only looked at the financial costs of CDL. It did not include any of the social and environmental cost benefits. It also, did not factor in any of the ongoing costs to the community associated with not introducing CDL. For example, the growing amount of ratepayer money that local government in Victoria must spend each year cleaning up litter. Currently that cost is 40 to 50 million dollars. All up, more things need to be taken into account before we accept, without question, the view that ‘CDL will cost Victorian communities too much’. In South Australia polls have twice shown their refund system to have a public approval rating of about 80%. This suggests that for most South Australians the benefits of their system outweigh its costs. Further evidence that CDL has widespread public support was seen in a Newspoll survey, conducted in Western Australia in June 2006. It found that 94% of the population supported WA’s intention to introduce deposits on containers. It is appropriate to conclude with the issue of cost, because it leads to the important question; Can we afford to ignore the cost of not dealing with this problem? We know that many in the community are very concerned about the damage of drink container litter. We know there is a proven solution. For many years the large beverage companies have contributed probably hundreds of thousands of dollars to litter abatement programs such as Tidy Towns, ‘Do the Right Thing’, kerbside recycling, public place recycling, etc. However, litter and public rubbish, cost local governments millions of dollars (50 million pa in Victoria alone). The Beverage Industry Environment Council lobbies very strongly and makes these payments to litter programs, in the hope that other governments will not bring in CDL. According to the EPA South Australia, (in the Consultancy Report, ‘Container Deposit Legislation: Economic and Environmental Impacts’, published in 2000), the cost to beverage filler and distributor companies, of CDL in SA, is $14.9 million per annum, which is less than 1% of their annual profit. (Most of this cost is spread across the country. They estimate that South Australians pay $2.22 each per annum and the rest of Australia 61c each per annum to cover this cost). It doesn’t seem right that these large multi-national companies, which make annual profits of several billion dollars, can pay a few hundred thousand dollars for litter abatement, instead of paying for the real damage and waste that their throw away products cause. No wonder CDL is not wanted by these companies. We hope that industry, as good corporate citizens, will accept the fact that we cannot continue the present course. We hope industry (beverage, packaging, retail and waste companies) will stop blocking and will support the introduction of Container Deposit Legislation. We believe that the overall feeling in the community is that it is time to act on this problem. 25 SECTION THREE 4) RECENT DEVELOPMENTS In the last 2 years a number of Parliamentarians in Victoria, Tasmania, Western Australia, the Northern Territory and Queensland, have made speeches about the need for CDL in their States. Support has come from other sources also. One example is a submission made in 2004, by the Tasmanian branch of the Waste Management Association of Australia, to a Parliamentary Inquiry into ‘Waste Management in Tasmania’. The association expressed the view that “container deposit legislation and extended producer responsibility have a significant role to play in the future.-- will assist with litter reduction (vital to Tasmania’s image), waste minimization, impact on waste to landfill and increased product recovery rates.” More recently, the government in Western Australia, in 2005, set up a Stakeholders Advisory Group to advise on the best model of CDL for WA. Also, the Northern Territory has begun to set in motion an investigation into a CDL scheme for remote communities. Unfortunately, progress in Victoria seems to have stalled. In 2005 the State Council of the Municipal Association of Victoria, called for the Packaging Covenant Council and the State Government to finance an investigation of a CDL model for Victoria. As yet, nothing has happened. Public support for CDL is very high and goes across all age groups, occupations and where people live. People see CDL as a practical, common sense approach that works. If government wants to fix this problem, CDL is a system which the community will support. The author with Mr Ted Barker of Hamilton. 26 BEVERAGE LITTER SURVEY NAME: TOTAL MELWAYS REF. FROM: NA TO: NA DISTANCE: NA APPENDIX A NON BEVERAGE LITTER ALUMINIUM CANS PLASTIC BOTTLES GLASS BOTTLES TETRA PACKS e.g. PRIMAS CARTONBOARD e.g. BIG M CARTONS PAPER CUPS POLY CUPS ** If applicable underline one side of road or both sides of road. TOTAL= 27 Comments: 0 APPENDIX B Mr J Jones ‘Adopt a Highway’ Coordinator Dear Mr Jones, As explained on the phone I am currently researching roadside litter. As part of that work I am surveying individuals and community groups involved in formal or informal clean ups as well as groups involved in Vic Roads ‘Adopt a highway’ scheme. Please find below the survey I spoke of. The purpose of the survey is to find out what your work with litter has revealed about roadside litter and specifically what proportion of it is drink container litter. The information that you provide will be collated with survey results from all over Victoria and presented to government. It is my hope that contributions from the community, such as yours, will lead to the introduction of more effective litter prevention and litter reduction strategies. Thank you once again for your contribution to this process. Mr P Cook SURVEY 1. From your involvement in litter clean ups, would you describe beverage containers ( bottles, cans, flavoured milk cartons and cardboard and polystyrene cups) as being a very small, small, medium or large or very large proportion of the litter collected? Please circle or underline Very small, small, medium or large or very large. 2. If medium, large or very large, which of the above types of beverage litter is most common? Please circle or underline glass bottles, plastic bottles, cans, flavoured milk cartons, cardboard cups or polystyrene cups. 3. Comments: PTO Thank you very much for your contribution to my research into roadside litter. Please mail this letter / survey back to me at or email your survey results to me at What is the purpose of my research? I am presently doing surveys of country and metropolitan roads throughout Victoria. In those surveys I am counting the amount of beverage litter. The feedback you give me via the questions above will help me work out whether my results are consistent with your hands on experience. 28 APPENDIX C Community Groups and Individuals Surveyed The authors would like to thank the following community groups for their contribution to the Community Litter Survey. We would also like to thank those individuals who completed a survey focusing on the area in their local community that they regularly clean. ‘Adopt a Highway’ Castlemaine Church of Christ Castlemaine Field Naturalists Club Broadlands Landcare Gunbower Landcare Group South Yarrawonga Landcare Group Toms Creek Landcare Group Bendigo Lions Club Euroa Lions Club Ouyen Lions Club Sea Lake Lions Club Wycheproof Lions Club Friends of Police Paddocks Rowville Friends of Traralgon West Railway Reserve Friends of Warringine Park GLADE (Group for Lilydale & District Environment) Horsham Secondary College Rainbow Secondary College Horsham Secondary College McKenzies Creek Campus St Arnaud Secondary College The Rotary Club of Bairnsdale The Rotary Club of Bendigo-Strathdale The Rotary Club of Camperdown The Rotary Club of East Shepparton The Rotary Club of Echuca The Rotary Club of Foster The Rotary Club of Kerang The Rotary Club of Mansfield The Rotary Club of Mt Martha The Rotary Club of Nathalia The Rotary Club of Traralgon Central The Rotary Club of Warrnambool The Rotary Club of Warrnambool East The Rotary Club of Wonthaggi Ouyen Tidy Towns Committee Cohuna Progress Association Guildford Progress Association Toora Progress Association Wildlife Rescue and Information Network Stawell Secondary College Other Community Groups and Individuals Bayswater Stationeers Ringwood East Stationeers Southwood Boys Grammar, Heathmont Stationeers Upwey Stationeers Croydon Green Team Don Valley Landcare Group Emerald Clean Team Friends of Blind Creek Friends of Cardinia Creek Sanctuary Friends of Chiltern National Park Friends of Glass Creek Parklands Friends of Redgum Triangle Olinda Action Group Steeles Creek Community and Yarra Glen Tree Group Andy Ambrews, Akoonah Park/Beaconsfield Cricket Club Pipa Goodie, Avonsleigh Judy Smith, Beaconsfield Flora & Fauna Reserve Trevor Currell, Marg Stanton, Judy Stiff, John Mortimore, Daniel Proudfoot Bruce Thomson, Murray Thomson We would also like to thank the following individuals who helped us with our roadside surveys. Gaye Cranfield. Belinda Gibson. Darren & Fiona Wallace. 29 APPENDIX D About the Authors Peter and Marion Cook have been involved with a number of community groups over several years. These include the Mt St Gwinear Ski Patrol, Friends of Mt Rothwell Sanctuary and St Johns Hill Land Care. Through these and other organisations they have been regular participants in litter clean ups. The Cooks have a love of the Australian bush. On their many travels they have become very concerned about the amount of drink containers on our roadsides, in the bush and in waterways. This concern has made them determined to bring this problem to the attention of others. Early in 2005 they established a group called AFROCAB (Australians For Refunds on Cans and Bottles). Shortly afterwards they attended a local market to promote the need for deposits on cans and bottles. In just over two hours nearly 300 people signed up as AFROCAB supporters. This was typical of the response at several forums that they have attended. They have found that support for a deposit system goes across all ages and backgrounds. People see the deposit system as a logical and common sense way of addressing the drink container litter problem. Many middle aged and older Australians are supportive because they remember how well the deposit system on glass soft drink bottles worked in the 1960’s. Other people have experienced the success of the system in South Australia. The positive response from so many people encouraged the Cooks to investigate for themselves the truth about the litter situation. This Community Litter Report is a result of that research. They hope that this report will help convince governments that existing litter policies are not working and that alternative approaches are needed to solve this problem. 30