Working with complex needs in the classroom

advertisement

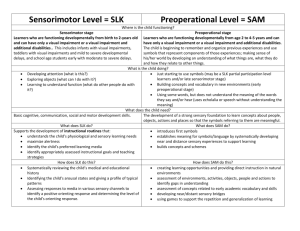

RNIB supporting blind and partially sighted people Effective practice guide Working with complex needs in the classroom Using play, stories and creativity can make the classroom a useful place, and a fun one, for children with complex needs and vision impairment. This guide looks at developing play, information and communications technology (ICT), multi-sensory environments, creative and musical sessions, and sensory stories. It includes ideas and suggestions for lesson activities, considering your classroom environment and sourcing and producing resources. Contents Part 1: Developing play Part 2: Information and Communication Technology (ICT) and complex needs Part 3: Multi-sensory Environments Part 4: Music gets us going! Creative and Musical sessions for children with complex needs including visual impairment Part 5: Sensory Stories Part 6: Further guides Registered charity number 226227 Part 1: Developing play About this part This part explores how and why we should aim for high quality play experiences for children with complex needs. Written by Mary Lee, Principal Teacher for staff development at the Canaan Lane Campus of the Royal Blind School in Edinburgh, Scotland. Mary runs the multi disciplinary assessment team and is involved in the early years service for young pre-schoolers. She is a co-author of 'Learning Together', a book outlining innovative methods in communication and play for children with multiple disabilities and visual impairment, including the Canaan Barrie tactile signs. Contents: 1.1. Why is play important? 1.2. Obstacles to play for children with vision impairment and complex needs 1.3. What should we do? 1.4. What are we aiming for? 1.5. Techniques to support early development 1.6. Individual play styles 1.7. Questions to consider 1.8. Next steps 1.9. References 1.10 Further reading 1.1. Why is play important? Play is one of the most important areas in the education of children with vision impairment and complex needs. Children operating at the earliest developmental levels learn through play. They are not yet ready for more formal learning. However, the curriculum in so many of our schools is based on adult-directed learning. This uses methods that are more suited to children who have already gained a whole background of knowledge about themselves and the world around them. It takes a lot longer for children operating at the earliest developmental levels to build these concepts. This means they still need to learn through independent, self-directed exploration. At this stage, children learn by doing, and by trial and error. They are finding out what effect they can have on the world. In so doing, they are building their own self-image ("this is me, this is what I can do"). Without this knowledge, it isn't easy to learn from others or have a concept of what's in another person's mind ("this is what he wants me to do"). In order to learn from instruction, each child needs a background of personal experience to relate back to. 1.2. Obstacles to play for children with vision impairment and complex needs For children with vision impairment and complex needs, the greatest obstacle to play is the vision impairment itself. Children with little or no vision know less about what's out there to explore, and may not be attracted by the interesting colours and shapes that would motivate a child with vision. It's also more difficult for them to share their interest with someone else and communicate about objects (joint attention) through the conventional visual channels. The other obstacles might be: a child's physical difficulties, tactile defensiveness or tactile selectiveness that they may be receiving disjointed information from the senses, or that they may be feeling anxious about moving around in their environment. 1.3. What should we do? Vygotsky (1978) stated that children learn in a social context. We need therefore to provide support and help in an environment that feels safe and secure to the child. We need to intervene to provide the right materials to develop the child's play, provide help when it is needed and above all, no help if it is not required. This isn't as easy as it may appear. We have to keep a very open mind: children with a vision impairment may have interests and means of exploration which go against our expectations. We should never try to guide them into ways of doing things that are only relevant to our sighted world and may make little sense to them. We must be very careful to base our interventions on the child's needs and not interrupt the important developmental process of self-discovery. The following are really important aspects in the development of play. Sadly, they can be missed in the atmosphere a busy classroom. 1. Give enough time Children with a vision impairment and complex needs, need to be given sufficient time to explore on their own. This may not be a simple matter of leaving a bit more response time. A child with a vision impairment and complex needs may need an entire afternoon to allow them to relax in the environment; to become aware that this is their time and that they won't be being guided by an adult in the way that they're used to during other timetabled activities. The child will need to bring their consciousness to the task in hand and become familiar with an object, before feeling able to explore. Time has to be set aside for play; it cannot be fitted in as a filler between other "curricular" activities. For these children, play is the "core curriculum". 2. Provide an appropriate space Space is a very individual thing. Many children prefer a lot of space around them, so that they can feel in control of that space. They may feel anxious about other people acting in an unpredictable fashion close by. Others prefer their space to be confined, so that they know exactly how that space is defined. Lilli Nielsen, a Danish educator, devised the "Little Room" (a small enclosed area for the child to lie inside) for exactly this purpose. In the Little Room, objects are hung around the child. Any movement they make gets an instant response through tactile and auditory feedback. This helps the child to gain a sense of their own agency. (See our Early Years Series Guide on 'Treasure Baskets' for more information on Little Rooms.) 3. Offer the right equipment Everyday objects can often be rewarding for children with complex needs. Many children with vision impairment enjoy push-button toys which play music and other sounds. However, while these toys may give pleasure, once a push button toy has been mastered there is little further learning involved. As an alternative, many educationalists advocate the use of everyday objects (from metal spoons to door hinges to sponges) as playthings for children, sighted and non-sighted alike. These objects have a wealth of interesting shapes, textures and sounds to explore. There is no one way of using them and they positively invite creativity as the child seeks to find different ways of encountering and using them. The RNIB Toy column which appears in Insight Magazine lists mainstream toys that have been chosen for children with vision impairment, including those with complex needs. 4. Ensure a supportive environment Additionally, our job is to create a safe environment in which the child sees our presence as supportive, providing what Elinor Goldschmeid (1987) has called a "safe anchorage". The adult is observant and attentive, but not interfering. We can use the time to note the child's interests and motivations. If the child appears to be interested in making comparisons between different sounds, then we can bring objects close to the child that may expand on that interest. If gross motor play is on the agenda, then we can introduce a rocker to the child's area. We are building on and varying the child's play without directing it. If we are picking up on the mood and motivations of the moment, then our newly introduced objects will more than likely be accepted into the child's play. 1.4. What are we aiming for? The ultimate aim of play is to encourage children to think for themselves. If we don't provide such experiences for them, then we may cause the child to think that nothing happens in their world, unless an adult is there to provide it for them. That all-important sense of self will not emerge. 1.5. Techniques to support early development The little room Children with vision impairment and complex needs are working within what Piaget called the 'sensori-motor' stage of learning. Lilli Nielsen's 'Little Room' addresses these early stages very effectively. Working within the 'Little Room', the child first gains a sense of his own agency. The instant auditory feedback from the walls of the room lets the child know that he is the one who made that sound. The hanging objects when hit or swiped will always return to their original position, thus enabling the child to develop a sense of 'object permanence'. Gradually through repeated experiences, the child gains an understanding of 'cause and effect' - 'when I did that, this happened'. Once 'cause and effect' is understood, the child can begin to develop preferences and ultimately make choices of which objects to return to for another go. With time and experience, the child begins to develop more varied exploration. The resonance board Another useful piece of equipment developed by Lilli Neilsen is the resonance board. This is made of plywood and sits on a frame about one inch from the ground. The child sits or lies on this and again gains instant feedback from his activities, feeling the effect through his whole body. Lilli Nielsen's research found that children with visual impairment, placed within the 'Little Room' or on a resonance board, were considerably more active in their play. Everyday objects At the end of the sensori-motor period, children develop problem solving skills. Firstly through trial and error, but later they develop mental problem solving skills, ie the ability to work a strategy out in their heads before taking action. For many children with complex learning needs, this is our ultimate aim, the ability to work out their own ideas and act upon them. Everyday objects are excellent tools to use in the development of problem solving skills. The objects are extremely versatile and there are many ways of combining and using them to gain different effects and outcomes. In playing with everyday objects, the children are given the opportunity to find out firstly what they are and what they can do. Subsequently they develop such concepts as putting in and taking out, building up and knocking down, heavy and light, large and small - the list is endless. 1.6. Individual play styles While children with vision impairment are building the same concepts as any other children, they may have very different ways of doing this. Observing the children at play can be a fascinating and rewarding activity. Certain typical features emerge. 1. Body-centred play To begin with, the play tends to be body-centred. The child with vision impairment may be testing out, not what the object can do in relation to other objects or to space, but what it can do for him or her. The child may twirl around with the object to feel the air currents against his face. Shape may be explored by moving the object across the body, rather than by following an outline with the fingers. The mouth is frequently used for sensory feedback. 2. Sound and timing Sound, rhythm and timing are likely to play an important part in the child's explorations. Once an object with a rewarding sound has been discovered, the child with vision impairment may experiment using rhythm and timing to find out what are the properties of this object. 3. Movement Movement is likely to be important - both the movement of self and the movement of objects. When no objects are present, many children with vision impairment will play with movement alone. What can look like stereotypical behaviour may well be an exploration of a particular movement, large or small. The child may be seen to be changing rhythms or experimenting with heavy and light, or tension and relaxation in a part of the body. Far from being stereotypical, it can be a conscious exploration. Commonly children with vision impairment enjoy gross motor activities, rocking, sliding, jumping, swinging, as it gives them a sense of their bodies in space, information normally gained through vision. Using hands to explore? For a great many children with a vision impairment and complex needs, hands may not be the main means of exploration. Many have become defensive of their hands and will prefer to use their feet, mouth or other body parts to explore. Taking this into account, very little is gained by sitting children with a vision impairment and complex needs at tables and expecting them to play with their hands. Far more can be gained by allowing them to approach the world in whichever way suits them best, by observing their preferences and creating an environment that supports their developmental needs and preferred means of exploration. These children will learn what they themselves are capable of, building a self-image with confidence and understanding. In this way they are working towards being able to learn what others do; being able to participate with and understand what motivates others, coming, as they should, from a firm basis of self knowledge. 1.7. Questions to consider Do I give the child sufficient time to make their own discoveries? Have I created a safe space for them to play? Do I truly observe and pick up on their learning style? What senses does the child use predominantly in play? What developmental level is the child working at? What preferences does the child show for sound, texture and etc.? How do I support the child's play? Do I communicate my understanding in a way that the child can make sense of? 1.8. Next steps For children operating within the next stages of development, a useful play schedule has been developed by Linda Hubbard based on Tina Bruce's 12 Features of Play. Linda has outlined the play interests of children with vision impairment who have reached the level of social / pretend play. 1.9. References Lee M and MacWilliam L. (2008) Learning together, a creative approach to learning for children with multiple disabilities and visual impairment. Chapter 5: Exploring the environment, play and active learning. RNIB, London Lee M. (2005) This little finger: an early literacy pack for parents of children with visual impairment. Chapter 2: Play. 1.10. Further reading For further information on how to work alongside and develop the play of children and young people with vision impairment and complex needs, please see: Atherton J.S. (2005) Learning and Teaching: Piaget's developmental theory. Accessed 27 January 2000. Bruce T. (2004) Developing learning in early childhood. Sage publications, London Goldschmeid E. (1987) Infants at work (VHS). National Children's Bureau Enterprises Ltd., London Goldschmeid E. (1987) Heuristic play with objects (VHS). National Children's Bureau Enterprises Ltd., London Goldschmeid E. and Jackson S. (2003) People under three: young children in day care. Routledge, London Haughton L. and Mackevicius S. (2004) Little steps to learning: play in the home for children who are blind or vision impaired 0 3 years. Royal Victorian Institute for the Blind, Melbourne Haughton L. and Mackevicius S. (2001) I'm posting the pebbles: active learning for children who are blind or vision impaired. Royal Victorian Institute for the Blind, Melbourne Neilsen L. (1992) Space and Self. Sikon, Denmark Neilsen L. (1993) Early learning step by step in children with vision impairment and multiple disabilities. Sikon, Denmark Vygotsky L.S. (1978) Mind in Society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. RNIB & BTHA 'Toys and Play' Information Leaflet RNIB in partnership with The British Toy & Hobby Association (BTHA) have produced an information leaflet on toys and play for children who are blind and partially sighted as part of a series of BTHA funded educational literature. You can download the leaflet at our Guidance on teaching and learning section. Part 2: Information and Communication Technology (ICT) and complex needs About this part This part focuses on Information and Communication Technology (ICT) for children with vision impairment and complex needs. This guide is written by Dave Wood, Qualified Teacher of the Vision Impaired (QTVI), and formerly an Independent Consultant in Special Educational Needs and ICT. In this guide Dave explores the use of ICT, drawing on his experience of training staff in Children's Centers in Leicester on ensuring that children with special needs have equal access to ICT. Contents: 2.1 Why use ICT? 2.2 Switches 2.3 Switch output devices 2.4 Speech output devices 2.5 Software programs 2.6 Creating the ICT environment 2.7 Sourcing ICT equipment 2.1. Why use ICT? All children gradually develop the means to influence others, and this usually evolves through trial and error and the copying of others. Many children with complex needs and vision impairment have fewer opportunities for incidental learning and therefore benefit from help in organising their experiences, and creating opportunities for them to communicate their preferences and choices. ICT in all its forms can help to: shape understanding of cause and effect present opportunities to exercise a choice take part in a group activity control the actions of others gain access to recreational activity. 2.2. Switches Many children with complex needs using ICT, start to access it using a switch. Switches can take many different forms, from pushbutton types of varying sizes, shapes and textures, joystick-shaped switches, toggles, beams of light which can be broken by movement of the hand or arm, and many more. If a child has some level of independent movement, it is likely that there will be a switch that can be found which will use that movement to operate the switch. Positioning a switch Positioning a switch correctly can be equally as important as choosing the right type of switch for the child. It is important to consider the range of movements of the child, and use of any residual vision, and to find a switch position that enables the child to have the best control and most comfortable use of their own movement when they access the switch. It is also worth considering if the hand or arm is necessarily the best body part for the child to use in accessing the switch. In some cases head movement, or use of the feet or legs is preferable. Switches can be positioned: in front of the child on a wheelchair tray or table to the side of a child or higher than table level, using a mounting stand in the headrest of a wheelchair on the floor for a child lying down or using positioning wedges near or around the feet 2.3. Switch output devices Switches can then be connected to a variety of output devices, giving the child control of an object, computer programme, toy or game. Most electronic products with an on/off capacity can be adapted for use with a switch. Some multi-sensory activities, for example using a switch-adapted battery fan can be presented almost anywhere, and be made available for the person to use when they want. The "waker shaker" with switch adaptation provides a strong vibration and can be fun putting it on feet, chin, up sleeves (for those with poor grip) or on the back of the neck. Response to this are usually very apparent, but be cautious of surprise responses being misinterpreted as dislike. A battery toothbrush, (with brush removed) is a gentler source of vibration, and they often come with a twist mechanism to stop/start that provides another example of control. There is also a large number of switch adapted toys available that enable the user to cause a lion or a pig or a butterfly to perform a small action by using the switch. 2.4. Speech output devices Interactions with adults and other children can be enabled by speech output devices, which are often more fun if they tell a joke, or ask for a bit of peace and quiet, or enable a child to give one (repeating) word of a story. There are many varieties, and cost varies from the Talking Tin lids (3 for £20), through to the BIGmack (approx £90 rrp). Speech output devices can be used: as a prompt for speech as a memory aid for someone shopping (older children and adults) communicating a choice of activity or food etc. to involve the child during circle time or a story-telling activity saying a prayer in assembly reminding the child of work they have done out of class with a therapist. 2.5. Software programs More sophisticated interaction becomes available with the wide variety of software now available which together with touch screens and very large plasma touch monitors give larger target areas for touch, and the chance to engage in a group activity. These can help to develop understanding of cause and effect, and choice-making possible for children working at the earliest levels. Some programmes only ask that the user engages visually and to help them the images are presented clearly against backgrounds with a good contrast. Some now provide the means to change colours to suit individuals and to graduate the speed of action. Switch access to the computer is usually by a "switch interface", a box that plugs into the back of the PC and has a jack socket for the switch. 2.6. Creating the ICT environment Presenting the hardware Using different height, or even height-adjustable tables can enable a desktop PC can be presented at different heights and angles. A simpler solution however, can be to use a laptop with children who spend time on the floor and in standing frames or side-lyers, and switch use is often enabled because children do not have to concentrate on keeping their balance. The visual environment Before the child is asked to engage, remember to check that there are no reflected lights or highly coloured wall displays that are seen by the child at the angle at which they are looking. Place yourself at their height to check that you can understand the set-up from their perspective. Some children also find the screen too bright, and a sheet of pink, green, blue, yellow Perspex draped over the monitor can reduce glare enough to allow a child with light sensitivity to see the images presented. Remember that many children adopt a preferential looking position that may be as much as a right angle to the image presented. It is known that some effects of nystagmus can be reduced by achieving a "null" point where vision is least affected, and many other children with visual field losses will want to be in a position where they can see best. Midline, upright, facing the screen may only be a good position for a few. 2.7. Sourcing ICT equipment There are a number of different companies which offer ICT equipment. These can be found online using a standard search engine such as Google. Companies include: Inclusive Technology Liberator Ltd (AAC) and more… Part 3: Multi-sensory Environments About this part This part focuses on creating a Multi-sensory environment for children with a vision impairment and complex needs. This guide is written by Flo Longhorn Consultant and Author in Special Education (flocatalyst@aol.com). Flo shares her views on this approach exploring what a multi-sensory environment is and exploring in more detail, the visual system. Flo has worked in the international field of education since 1970, with particular emphasis on special education, including expertise in severe and profound disabilities, challenging behaviour and special needs education. She is an acknowledged expert in multi sensory education and multisensory environments. She has held senior management posts in education, including headships of UK special schools. Contents: 3.1 What is a multi-sensory environment? 3.2 The Visual System 3.3 Touch and Vision 3.4 Sound and Vision 3.5 Smell and Vision 3.6 Taste and Vision 3.7 Vestibular/ Proprioceptive senses and vision 3.8 Further Reading 3.1. What is a multi-sensory environment? 'I look with my nose, my mouth, my movements, my ears, my skin and my eyes -a multi sensory approach to vision for children with visual impairment and complex needs. What do you see below? Now, what do you see below? If you looked and saw a green and a red apple, well done! That was easy wasn't it? But just think about the range of information you had to collect from your brain's memory in order to make sense of what you saw in the images. Your brain had to collect information from seven sensory systems in order to recognise the images. The brain went to… the visual system to scan and transport the visual image to the memory bank to identify what the image was and give it a name the sound system held the memory of the chewing and biting noises when eating the apple the smell system retained the apple smell the vestibular and proprioceptive systems( movement) recalled how to pluck an apple from a tree or a bowl the touch system reminisced about the textures, temperature, weight, shape and firmness of an apple to find stored memories of what an apple 'is'. The brain needed more information than just an image of the apple. The visual system also relied on all the other senses sending pertinent information to make sense of what was being viewed. By just isolating vision and working on this one sensory area is a mistake, vision must be seen a part of a complex multi sensory network of sensing, perceiving, learning and understanding for any learner. The brain needs many connections using all the senses in order to make sense of the world around. In order to make sense of what we see, there needs to be an awakening of not only vision but all the other senses for the very special learner. It is essential that sensory approach is used for learning to sense, perceive and read the visual world that surrounds a child with a vision impairment and complex needs. The seven sensory systems are vision touch sound proprioception ( movements and body maps) vestibular (balance and position of parts of the body) smell taste When we use two or more senses together this is called 'multi sensory'. We 'see and touch' or 'look and listen'. 3.2. The visual system Vision is the major coordinating system and a large part of the brain is taken up with seeing, looking, understanding and memorising what is seen. It is the quickest and most efficient way of investigating and discovering the world around. The visual information is channelled through the eyes, along the optic nerve to the major areas of the brain dealing with vision. Each visual image we see is constantly analysed for information such as depth, colour, movement or 3D viewing. The main function of vision is to collect information such as: observing objects near and far away viewing in depth seeing at the edge of vision-out of the corner of the eye seeing colours in all their changing hues viewing shades of contrast and lighting seeing fine details getting the whole picture ,not just a fragment understanding what is being viewed If you put the light on in the dark room, for example, the brain has a bustle of activity because, even though the room has not changed, all the visual aspects have. The floor has changed colour, the table is in shadow, the trinkets on the table have a different depth, the windows changed colour, perspectives have changed......a busy brain! Here are a selection of materials that will engage not only vision, but other senses to develop a range of skills needed for seeing and understanding for a child with a vision impairment and complex needs: small intense led light torches revolving colour light toys vivid UV* light materials black and white images of faces photos of faces a stick with a piece of dangly ribbon attached Ipad with specific apps of intense light programmes mirrors, including concave and convex a trail of battery run fairy lights glitter gloves, nail varnish and gold tinsel * The use of UV lighting in a programme of visual stimulation should be done with the full knowledge of the medical condition of the child and with guidance from the Qualified Teacher of the Vision Impaired (QTVI ). Now use these materials to develop visual skills in conjunction with other senses. For a child with a vision impairment and complex needs who requires an awakening of their visual system. For example, using the lights and torches to: Track slowly from side to side. Up and down slowly. Across the body midline. Try a wobbly line of light. Illuminate your face. The child's hands. Look in a mirror with the torch. Try faster movements of the torch. Make a slow figure of 8-vertical and horizontal. Try the activities with different beam colours and in different room lighting. Now use face images illuminated by torchlight to gaze and fixate upon. How about regarding some intense visual vibratory images together. Use gold gloves to highlight hands, entwine tinsel around fingers and highlight nails with glitter polish. Best of all use, the latest technology with the following sensational interactive Apps from the Ipad. Some are listed below can be used for stimulating vision and are amazing! The good-sized screen can be brought up to within close range of the nose of a child if necessary! The slightest interaction evokes an active engagement. Multi sensory visual 'Apps' for learners (Available at: www.Itunes.com) Glow draw-sensational intense fluorescent colours, simply touch after choosing a colour to make intense marks. Colour spin-the whole screen is an intense colour that changes when touched, you can select different colour sequences. Pyromania-intense firework display with strong firework soundstouch and move finger to make a rocket or firework ignite. Koi Pond-oldie but goodie, lovely water sounds and friendly fish, great for sustained visual concentration. Balls- lovely sound linked to moving balls that move around when dragged with finger or nose. Rubber Ducky-garish spotted ducks that give really loud intense quacks when touched-great. Then you can change to plucky , stripe ducks..... Bobble Zoo-great fun, chose an animal and it appears with a wobbly head and the name is given, great for attention grabbing and prolonged gaze.. Bloom-gentler colours and relaxing music that move with the spots you create. With fingertips. Lines and Flowers- nice erratic tracking from different angles and different speeds.. Splode-very simple level of little creatures to track and touch so they go plop. Bubble Magic-different coloured moving bubbles that go pop when touched, super. Spawn Glow-fabulous, quick-moving lines of colour, controlled by a finger tip. 3.3. Touch and vision Touch is our largest sensory organ as skin covers the whole body and also inside our body. The touch receptors constantly send information to the brain so we have a sensory map of both outside the body and too. Can you sense your tongue inside your mouth and your feet inside your shoe, as you read this? Some areas of the skin are more sensitive that others especially the hands. Active hand (haptic) touch gives feedback about texture, pressure, temperature, weight, vibration and the outline and volume of objects. Clasp your hands together now and feel this happen! Now close your eyes and feel only your fingers touching, vision is needed to give more information than is felt through the skin only. Darren touches, explores and looks down to the textured materials in the basket. Try these ideas to link touch and vision together, for a child with a visual impairment and complex needs -working in a multi sensory way: Place a range of small textured articles in a basket, encourage looking at what the hands are exploring. Shine a torch on hands as they explore. Fill a hot water bottle with warm water, place hands on the surface, encourage looking as hands react to the warmth. Place a bowl of ice cubes for hands to explore and eyes to see what is so cold. Clap, clap, clap and clap feeling the vibrations and strong touch. Eyes can watch hands as they clap near and far away. Twist and thread silver tinsel, ribbons or coloured wools around fingers and bringing up to eyes so they can focus and see whilst feeling the materials. Place a vibrating toothbrush in a hand to see if the strong vibratory touch will encourage a visual exploration. Try the toothbrush on other parts of the body and encourage the learner to find where it is vibrating. “Paint” hands and feet with a paint brush, encourage eyes to watch and follow the firm brush strokes. 3.4. Sound and vision The sound system is closely related to vision. This is because each sound is usually linked to a visual map, as the ears and eyes locate the sound together. When we track a sound we usually turn to it, and then interpret the sound. Listen to sounds in the room as you read this page..........now check with your eyes that the sound you heard are in context and belong to an object, such as a ticking clock or a humming fan. Here are some sound activities linked to vision, a combination of sensory learning for the learner: Take a cup of rice and pour onto a tin lid, watch as the rice moves downwards and then hits the lid with a strong tinkling sound. Hide a set of bells in a bag, shake the bag and encourage eyes and ears to seek out where the sound is coming from. Crumple a piece of paper near each ear in turn, encourage the eyes to turn to seek the crackly noise. Use a hairdryer (on cold) to make a strong wind sound for the listener to hear and turn towards the sound. Perhaps the sense of touch will also help as the air hits the body! Place a tambourine under bare feet, encourage feet to bang and eyes to look down to see what is making such a noise. 3.5. Smell and vision Smell is the sensory system that perceives odours, using the nose. It links closely with emotions and can create strong emotions that recreate emotional experiences. The writer has just been to the dentist and the smells evoked some unwanted bad memories! What smells give you pleasant memories? There are usually emotional memories stirred by the smell remembrance. When using smell, only use two or three at a time as they can overwhelm. Offer the smell to each nostril to enable the smell to be assimilated properly. Try these smell activities as smell is usually a good motivator to look and seek out a tasty treat: Try smells that are especially liked by children such as banana or vanilla. Hold the smell or piece of food near the nose and then encourage looking for the source of the smell. Try a peppermint smell which really sharpens up looking and thinking. Put a strong smell such as herbal shower gel, into a bowl of water, encourage eyes to seek out the smell and play with the water. Try peeling an orange or lemon and sensing a reaction to such different aromas. Vick, for bad chesty coughs, is a strong odour to draw the eyes to the bottle! 3.6. Taste and vision Taste is found mainly on the tongue and links closely to smell. Taste is part of the routine of mealtimes and also having tasty treats for everyone. It links closely with vision as we usually look at what we are going to eat, especially if it looks appetising. Imagine looking at a plate of food that was coloured bright purple, our vision would send alarm signals to the brain 'this does not look good to eat!' Here are some tasty suggestions that will encourage a child with a vision impairment and complex needs to look with interest and attention: Take a sticky taste such as honey and smear on lips to encourage licking and tasting, show the honey pot to the learner so they see eat they are eating. Use an ice lolly to show what it is and then place on the lips or in the mouth for a cold sweet taste. Keep showing what is being eaten and naming the cold taste. Try placing a dessert such as Angel Delight, in a bowl to stick fingers in and then lick the sweet result. 3.7. Vestibular/proprioceptive senses and vision The proprioceptive system (to do with body positions, body maps and planning movements) and the vestibular system (to do with balance, head positions and gravity) work closely together for movements of the body. They are essential for vision as they are key to viewing the world from many angles, distances or in 3D, for example. Pick up an object near to you and examine it closely. Without coordinated movements you could not even reach out and maintain balance as you tried to grasp the object . Without these movement systems linking to vision, the eyes could not move and accommodate what they are seeing, or focus as the object comes close to the face or body. Here are some activities that incorporate movements with vision for a child with a vision impairment and complex needs, in a multi sensory way: Make some red sticky spots that will stick to the skin. Put one on a hand and the other on a knee. Use vision and movement to match the spots together, going across the body midline. Try the following 'Patting Story' which is very multi sensory, as it incorporates movements with touch and vision. You can pat the child as they face you, so they can see and perhaps mirror your actions back to you . Patting Story - The Lady Bird and the Spider. Story Line: Once upon a time there was a tiny ladybird “pat, pat, pat”! Patting Action: Fingers pat up and down both arms Story Line: Suddenly a large spider came spinning “spin, spin, spin”! Patting Action: Fists thump up and down the arms Story Line: And chased the tiny ladybird across the garden. Patting Action: Pat, pat, fingers up and down arms Story Line: Through a storm! Patting Action: Sweeping arm movements up and down Story Line: The wind blew “puff, puff, puff”! Patting Action: Pat cheeks and blow Story Line: The rain fell “tinkle, tinkle, tinkle”. Patting Action: Pitter, patter finger tips over head Story Line: The tiny ladybird ran up the hill to hide in the flowers on one side…. Patting Action: Strum fingers on one side of the hair Story Line: … and then on the other. Patting Action: Strum fingers on the other side Story Line: The spider followed into the flowers Patting Action: Thump thump all over the hair Story Line: When suddenly! Patting Action: Stop and hold up arms and hands Story Line: The tiny ladybird spread her wings and flew down… to find happiness in a warm heart! Patting Action: Flutter hands over the heart So, we have looked at all the sensory systems and begin to see how it is essential for them all to work in harmony with vision. A multi sensory approach is the way to learning to look with success. Now all we need to do is see how can we find out what will motivate the learner. How can we encourage them in a sensory way, to learn actively and with pleasure? The most sensory way is to do a 'Happiness Sensory Test' .You will soon pick up their communications that indicate 'wow! I really like that!' Here are two simple Happiness Checklists for your use: 1) Happiness Checklist Happiness is… The touch I like from humans: The tastes I like: Smells that make me happy: Sounds I like to hear: What I like to see best: Vibrations I like to feel: Touches I like from the world around me: Movements that stimulate me: Multi sensory environments that please me: What I like best of all... 2) Happiness Checklist What makes me happy to look and learn… My Immediate Environment: My Preferred Sensory Input: My Preferred Style of Learning: Preferred Friend(s): Preferred Grouping: Preferred Materials and Equipment: Preferred Style of Interaction: Preferred Personal Leisure Activities or Obsessions: N.B It is important to note here that some children undoubtedly prefer to use a single sensory channel at any one time. For these children a multi-sensory approach may not be appropriate. 3.8. Further Reading Books of interest Fowler, S. (2008). Multi sensory rooms and environments: controlled sensory experiences for people with profound and multiple disabilities. Jessica Kingsley. Pagliano, P. (2001). Using a multi sensory environment: a practical guide for teachers. David Fulton Publishers. Longhorn, F. (2008). Waking up the senses: the sensology workout, Flo Longhorn publications. My books on multi sensory approaches to learning for very special children and adults can all be found at www.amazon.co.uk by putting in 'Flo Longhorn'. Fowler, S. (2006). Sensory stimulation: sensory focussed activities for people with physical and multiple disabilities, Jessica Kingsley. Southwell, C. (2003) Assessing functional vision for children with complex needs, RNIB. Aitken, S & Buujens-free, M (1991). Vision for doing. Tullet, H (2005). The five senses, Tate Gallery Publishing. Calvert, G et al (2004) The handbook of multi sensory processes, MIT press. Part 4: Music gets us going! Creative and Musical sessions for children with complex needs including vision impairment About this part This part focuses on musical development for children with vision impairment and complex needs. Written by Sally Zimmermann, Music Adviser at RNIB. The Music Advisory Service can be contacted at mas@rnib.org.uk This guide looks at the importance of musical development in children as well as identifying practical strategies to engage children. Contents: 4.1. The purpose of Music 4.2. Music and Vision Impairment 4.3. Using Music in Practice 4.4. Music and Independence 4.5. A group approach 4.6. Further Reading 4.1. The purpose of Music Music is made of sounds organised in particular ways. These organised sounds usually have pitch (high/low), rhythm (different lengths), loudness (volume), timbre (the quality of sound that makes the same pitch on a bell sound different to that on a flute). These musical sounds can be one at a time or several at the same time. These sounds are arranged in time, often with considerable repetition (particularly in Western music) along with some silences. Music can be just listened to (or just "on in the background"), danced to, used with pictures or moving images, part of celebrations. Music can be live or recorded or a mixture of both. Music is used to bring us together, from singing on the football terraces to cake and a chorus of Happy Birthday in a restaurant. It is also used by us to retreat into our own world, complete with ear phones on the bus and train. It makes us feel happy. It gets us going. It calms us down and relaxes us. It can seem sad to us or happy to us. Music is everywhere and in the 21st century at the press of a button we can magic music from any time past or any place in the world on a computer. We can "hear" music in our head. We have music that is personal - "they are playing our tune" where a memory of a specific time, place, smell, company is recalled by a mere snippet of music. We have music that binds communities, as in hand across the chest for US citizens at the first notes of their National Anthem. Music happens in time and space. The space may be straight into our heads or a living room at home or a field at a pop festival. We respond to music heard whilst we are in the womb for about the last three months of gestation. Music is the subject we start learning pre birth! Most cultures then spend a lot of time with music and movement and touch from birth to the stage of walking and talking. This musical activity is imbued with parental warmth, human contact, as we sing and rock babies to sleep in our arms, bounce them up and down on our laps and try to make changing the nappy fun. 4.2. Music and Vision Impairment To the child for whom sound is more important than sight, all the above is particularly important. Sighted people stay alert by shifting focus on different things continually, changing the picture, selecting the picture, whilst shutting out a lot of the noise around (the printer, the traffic, the air conditioning). Sit comfortably, close your eyes and listen to the world around for five minutes. How still were you? What kept your interest? Did five minutes seem longer than you were expecting? There are all kinds of sounds that have a pattern to them that can hold the attention of children, especially if a significant adult shares the experience. The running tap, the washing machine cycle, the printer. All these sounds from one particular place help a child who cannot see know where they are. Some are linked to smells as well. Mum's voice sounds different in the bathroom to the living room. Preparing for a meal might have a whole sequence of musical sounds - shaking the cornflake packet and putting it down on the tray top, getting the spoon from the drawer and then playing a rhythm on it as it comes closer to the tray, having a little song for the milk ending with "pour, pour, pour". Sounds purely for fun that move around, or moving around sound yourself, can get you going more than sound that comes from playing a tambourine at waist height in front of you or hearing a song from the speaker high on the wall. 4.3. Using Music in Practice Music moves us in two ways, physically and emotionally. It is very hard to listen to a piece of music with a heavy drum beat or repeated bass line without tapping your foot. For most children with limited movement or control of movement, there is still a strong desire to move. Once you have spotted movement related to the music, you know your child is listening. Using songs for when movement is needed, as in "This is the way we brush our teeth… comb our hair" makes routine more fun. Having a selection of songs and pieces of music to use for relaxing is handy too. Early mother child games often involve close physical contact, such as bouncing on the knee, along with singing and a game with a surprise at the end. The emotional tie to music is thus cemented. It may be important to keep this link of touch, movement and music going beyond earlier years. Live music often goes down better, whatever the type or quality, than recorded because of this personal approach. Singing close by a child helps them know it is a song for him or her. 4.4. Music and Independence Much of the music discussed above has been led by an adult. Having control over your sound world needs consideration as well. So being able to choose which track you hear is important. Using switches to control the computer or CD player, being able to sing a couple of notes from track and somebody recognise it and play the whole track, gives this choice for recorded sound. Have a selection of sound makers including those that make different pitched (high/low) sounds is also helpful. You can find some very light weight instruments, such as pagoda bells, which require very little movement, or breathe, to play. Check the child can actually hear their instruments in all the hurly burly. 4.5. A group approach Most music making is done in groups. Find songs which have a repeated pattern and then either a gap or change. Often in a silence a child vocalises or moves or plays an instrument. Being silent around the child allows the child to learn "I did that". So if you are singing "I hear thunder" (to the tune of Frères Jacques) you could repeat the line "Pitter patter raindrops" over and over getting faster and faster, and moving around the child. Then make the "I'm wet through" sound as disgruntled as you can. A variation later on is to leave out the last word in each line and wait for the child to respond. Also listen carefully for humming of the first note which the child might do to get you to sing the song again. Many songs reinforce basic concepts such as songs that include "going up and down", "quickly and slowly" etc. Then there are songs about more specific things, such as leaves which can be scooped up and played with, moving at different speeds. Work songs such as "What shall we do with a drunken sailor" can have personalised lyrics (!) and are easily made dramatic, with in this case swishes and splashes. Using songs that other children are singing includes your child in everyone else's music making. Currently the Sing Up Songbank has some songs available for use with Clicker software and the audio tracks can be used by anybody who has signed up. The rehearsal tracks with gaps to repeat and then just the backing track are particularly helpful. The songs themselves cover all the Key Stage 2 curriculum. Musical ability in many ways is unrelated to other ability. Do listen out for Twinkle twinkle amongst a whole lot of "sound scribble" on the toy keyboard, or singing that just seems to be for fun. "If a child hears fine music from the day of his birth and learns to play it himself, he develops sensitivity, discipline and endurance. He gets a beautiful heart." —Shin'ichi Suzuki, founder of the Suzuki method of teaching instruments to very young children, now a world wide network. 4.6. Further Reading Corke, M. (2002): Approaches to Communication Through Music, London: David Fulton Geoghegan, L. (1999): Singing games and rhymes for early years, Glasgow: National Youth Choir of Scotland Lloyd, P. (2008): Let's all listen, London: Jessica Kingsley Shephard, C. and Stormont, B. (2005): Jubulani! Ideas for making music, Gloucester: Hawthorn Press ISBN 1 90 458 51 X Sing Up! Help kids find their voice: Jenny Young jenny.young@singup.org Sing Up Beyond the Mainstream Manager Bitesize Music September 2011 (Issue 35 Insight Magazine, RNIB). Part 5: Sensory Stories About this part This part focuses on Sensory Stories. Sensory Stories are stories which involve some or all of children's senses, including vision, taste, touch, sound, smell. Sensory stories can be used to include children with complex needs and vision impairment in literacy lessons. Written by Elizabeth Peirce, formerly Sensory Resource Co-ordinator at Brookfields School in Berkshire, this guide looks at how sensory stories work and explains how they have been developed by resource staff at a Brookfields School, in collaboration with the teacher responsible for literacy throughout the school. Contents: 5.1. What are sensory Stories? 5.2. How do sensory stories work? 5.3. Examples of sensory stories 5.4. Using the senses 5.5. Finding resources for sensory stories 5.6. Making sensory stories work in school 5.7. Considering individual needs 5.8. Books: Ideas for 'sensory' stories 5.1. What are sensory stories? Commercially-produced sensory stories are readily available and we have purchased them in the past. At the very least, they simply contain a book and small props to accompany the story. At most, they include tactile, auditory and olfactory elements of a reasonable size, based on familiar topics such as football. Staff at Brookfields School have developed sensory stories for use with all students, but which particularly enable pupils with a sensory impairment to be fully included. Building on this, we felt there was a need to produce sensory boxes around well-known and well-loved stories such as Handa's Surprise and Winnie the Witch. 5.2. How do sensory stories work? Our idea is that every story should engage all the senses. We also believe that, where possible, pupils should be encouraged to use their residual vision. All our stories involve using lights and include projected images or patterns. A story box is also provided. The story box contains the particular torches, lamps, lights and projector wheels needed to tell the story. 5.3. Examples of sensory stories Taste: Handa's Surprise Certain stories obviously lend themselves to the exploration of particular senses. For example, in Handa's Surprise, as Handa is delivering fruit in a basket to a friend, various creatures steal the fruits. So Handa's Surprise can be a taste extravaganza. Colour and touch: Winnie the Witch With careful story expansion, we have found that every sense can be included in all stories. Winnie the Witch has a black house and a black cat called Wilbur. Because everything is the same colour, Winnie keeps sitting on or falling over Wilbur, so she solves the problem by turning Wilbur into different colours, then redecorating her house. When reading the story, every time Winnie casts a colour spell, we projected a pattern wheel. For those pupils with poor distance vision, this can be projected on to a table or a wheelchair tray. Two green filter torches represent Wilbur's eyes. Enough fibreoptic light wands are included to enable every child (with or without assistance) to wave them when Winnie casts a spell. For pupils who can perceive a strong colour contrast, we provided a simple wooden house, painted black, and brightly coloured Velcro strips. The pupils attached a red roof, yellow walls and patterned carpet to the black house at the end of the story. 5.4. Using the senses Sounds Each sensory box contains a CD of sound effects in the order they appear in the story. For Winnie the Witch, these include the sounds of an angry cat howling and spitting, a variety of laughter and a cat purring loudly. These are not the only auditory elements in the story - the others are produced manually. The majority of our pupils process information very slowly. As many of the sounds are short, we either, simply repeat them, or amalgamate several on the computer, then burn them onto a CD to give a soundtrack of a suitable length. In future, we are hoping to include our pupils' own sound and music as part of the soundtrack for some of our stories. Soundabout is helping us to develop and record "songs" created by our students. Touch Tactile awareness goes on throughout the story. Smells are also generated through the story. Movement We incorporated movement into the story in many ways, for example putting hats on, stirring potions for spells, waving wands and (for physically able pupils) rolling over and over, when Winnie rolls into the rose bushes in the story. Taste This story doesn't lend itself naturally to taste sensations, but during our spell-casting, we "find" a bowl (porridge and honey) which we invite the children to taste, before deciding it is probably Winnie's breakfast and not a magic potion at all! 5.5. Finding resources for sensory stories Searching for suitable companies to supply our needs was initially time-consuming. Although we are very pleased with the companies we now use, they do not stock everything we require. Additional adaptations and purchases always have to be made. Seasonal shopping is highly recommended: Summer: bring back shells, driftwood, seaweed and toy seagulls from coastal resorts. Halloween: a perfect time for obtaining items for any witch stories. Easter: purchase straw hats, toy rabbits and toy chickens. Christmas: any stories involving stars, snowmen or fir trees. We always post a list of desired items on our staff board - people have the most incredible things in their attics. If you always have a wishlist for stories you are currently working on in the back of your mind, you'll find items in the most unlikely of places! Suppliers PuppetsByPost (01462 44 60 40): wide range of large hand puppets. Puppet Company: Large variety of puppets, very tactile. http://www.thepuppetcompany.com/ DaleAir (01772 68 77 22): vortex cube aromas. Store the cubes individually in small air-tight containers, especially if you are using several different ones in a story, otherwise they contaminate each other. We occasionally down load specific sounds from the Internet, but this can be costly. Although it was expensive initially, we purchased 1,000 digital sounds on ten CDs and found it an invaluable resource. Ultimate1.co.uk (0121 585 8001). Even with a thousand sounds available you will still find you have to record some sounds yourself. The real advantage with digital sound is that you can adapt it on a computer by cutting and pasting as you would with any other document. Wave Lab 6 from Music Village is a program which enables you to adapt sound. You may be able to get an educational discount. In addition, we have found the following stores very useful for certain items: Hobbycraft: large selection of artificial flowers and seasonal items. (They provide durable starfish - real ones are too fragile for some of our children to handle.) The Teddy Bear Factory: large number of clothing items and footwear ideal for puppets. Garden centres: larger ones stock garden ornaments such as scarecrows and realistic auditory birds. We sourced our 'cauldron' and broom from a garden centre. Toys 'R' Us: have a large selection of stuffed animals which they change frequently. IKEA: stock lights in a number of formats, unusual stuffed animals and toy tidies in a variety of shapes, eg pelicans and dragonflies. Fabricland: individual fabrics and other tactile materials. 5.6. Making sensory stories work in school We store the story boxes where everyone has easy access to log them out. They are large boxes with a full list of contents on the side. The only additional equipment you need is a CD player and a projector. At Brookfields, every classroom has a CD player and each Key Stage has at least one projector, CCTV and Interactive Whiteboards. We also have two portable sensory trolleys in school which can be used if further equipment is needed. Stories can be delivered anywhere providing there is a source of power and the ability to darken the area. Telling the story For staff who are less confident, full operating instructions are placed on each page. These can be used as a basis and embellished at will, depending on the specific needs of the group. We encourage staff not to feel that they have to deliver the whole story every time. Cliffhangers are good! The pace will obviously be dictated by the specific group, and it's also good to allow the pupils to experience all the objects before the story is even introduced. Ideally stories should be delivered on several occasions over a period of time, to enable pupils to become familiar with the content and begin to show anticipation and full involvement. 5.7. Considering individual needs Although ideally we would wish the stories to be totally inclusive, it is unrealistic to expect every child to take part in all activities. Pupils on the autistic spectrum may be very reluctant to touch, taste or wear items; and evidently, pupils with mobility problems may not be able to take part in all the physical activities. Teachers know the individual needs of pupils and adapt the stories accordingly. The children will often indicate what additional objects or activities could be included in a story and they will certainly let you know whether an activity is successful or not. We start from the premise that stories are by no means closed, complete entities. They are a starting point for a rich, inclusive, learning, sensory experience. Above all else, we aim to ensure they facilitate enjoyment: sensory stories should be enormous fun for everyone involved! 5.8. Books: Ideas for 'Sensory' stories Handa's Surprise by Eileen Browne. Walker Books, 1995. Winnie the Witch by Valerie Thomas. Oxford University Press, 1989. We’re Going on a Bear Hunt by Michael Rosen & Helen Oxenbury. Walker Books, 1993. The Very Lazy Ladybird. Isobel Finn & Jack Tickle. Little Tiger Press, 2000. The Happy Bee by Ian Beck. Scholastic Press, 2002. The Gruffalo by Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler. Macmillan Children's Books, 1999. The Snowman by Raymond Briggs. Puffin Books, Re-issue: 2009. 6: Further guides The full Complex Needs series of guides includes: Special Schools and Colleges in the UK Functional Vision and Hearing Assessments Communication: Complex needs Working with complex needs in the classroom The Staff team Understanding complex needs In addition, you may also be interested in the following series of guides, all of which are relevant to children, young people and families: Supporting Early Years Education series Removing barriers to learning series Complex needs series Further and Higher education series We also produce a Teaching National Curriculum Subjects guide, and a number of stand-alone guides, on a range of topics. Please contact us to find out what we have available. All these guides can be found in electronic form at rnib.org.uk/educationprofessionals For print, braille, large print or audio, please contact the RNIB Children, Young people and Families (CYPF) Team at cypf@rnib.org.uk For further information about RNIB Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB), and its associate charity Action for Blind People, provide a range of services to support children with visual impairment, their families and the professionals who work with them. RNIB Helpline can refer you to specialists for further advice and guidance relating to your situation. RNIB Helpline can also help you by providing information and advice on a range of topics, such as eye health, the latest products, leisure opportunities, benefits advice and emotional support. Call the Helpline team on 0303 123 9999 or email helpline@rnib.org.uk If you would like regular information to help your work with children who have vision impairment, why not subscribe to "Insight", RNIB's magazine for all who live or work with children and young people with VI. Information Disclaimer Effective Practice Guides provide general information and ideas for consideration when working with children who have a visual impairment (and complex needs). All information provided is from the personal perspective of the author of each guide and as such, RNIB will not accept liability for any loss or damage or inconvenience arising as a consequence of the use of or the inability to use any information within this guide. Readers who use this guide and rely on any information do so at their own risk. All activities should be done with the full knowledge of the medical condition of the child and with guidance from the QTVI and other professionals involved with the child. RNIB does not represent or warrant that the information accessible via the website, including Effective Practice Guidance is accurate, complete or up to date. Guide updated: July 2014