Beauty and Resilience:

advertisement

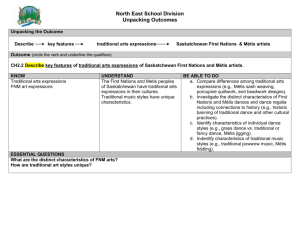

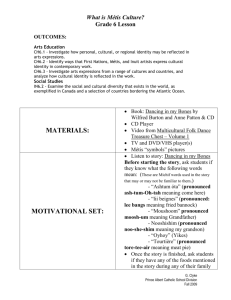

1 Beauty and Resilience: Reclaiming Métis History and Women’s Traditions in the Beaded Paintings of Christi Belcourt Rebecca Baird Contemporary Research Methods Professor Lynne Milgram and Barbara Rauch November 22, 2010 2 I have chosen to study the work of contemporary Cree-Métis artist, Christi Belcourt. I am interested in understanding the methods she is using from a shared cultural perspective. Her work exhibits a deep respect for the beauty of the natural world as it has historically been represented through the cultural traditions of Métis beadwork. Both Christi and I are Cree-Métis women who share a collective history as First Nations women. It is a history that is not separate from our artistic practices and methods of research which are bound by a ‘land’ memory and narrative and are distinctly historical, cultural, and by necessity, political. As Cree author Neal McLeod says, “There is a discord between ancient memory that is embodied in our lives and our physical being, and the experience of modernity and colonialism. These two sets of narratives and embodied ways of understanding the world are in conflict.”1 In his book, Cree Narrative Memory, McLeod references Cree poet Louise Halfe’s poetry collection Blue Marrow for her many insights regarding narrative memory: “She sees collective memory as a gift and intergenerational process, a way for Native people to find their way out of colonialism.”2 By analyzing Belcourt’s work, I will explore issues and methods that relate to the historical and cultural histories of First Nations' women artists and also how their methods relate to my own art practice. The research methods that I will use to analyze her work are methods similar to those she herself employs: a combination of both the scientific Western perspective and the time-honoured traditions of our shared ancestry. These methods will include observation, interviewing, self-discovery, grounded theory and historical investigations, self-reflection, technique and process, experimentation and interdisciplinary methods which include merging traditions. 1 Neal McLeod, Cree Narrative Memory from Treaties to Contemporary Times (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan: Purich Publishing Limited, 2007), 97. 2 Ibid., 9. 3 OBSERVATION, SELF-DISCOVERY, AND STUDIO PRACTICE Belcourt’s research methods involve a continuous process of self-discovery. She is a self-taught painter who also creates traditional beadwork from an historical identity. Her research techniques assume an objective quality of quiet observation of actual plants, which ‘speak’ to her in a variety of ways. After utilizing photography to capture and study the overall imagery of individual plants, she returns to her studio to carefully search for further information found in reference books about the plants and traditional Métis beading. Within the studio, she begins creative and critical research investigations to reimagine images using creative design methodologies. She pursues a rigorous sketching process, simplifying and reducing her field photographs into symbolic shapes reminiscent of the original beadwork of her Métis ancestors. Belcourt’s studio work strongly illustrates Graeme Sullivan’s theory of “artful thinking and mindful practice” as research. Historical Research into Métis Beading: Techniques, Patterns, and Women’s Teachings and Honoring Woven within her artistic practice is the knowledge that time and again Belcourt uses historical Métis beadwork patterns to honour the beautiful artistic legacy of her women ancestors, bringing a sense of continuity between the past and present Métis through her work. Although this may appear to be a form of anthropological research, she references her process not as an Other, but from her own center. Similarly, I feel that my own research is not an observation of Christi Belcourt as an Other but as a ‘sister’. In the process of researching historical Métis beading techniques, and in addition to the beadwork designs themselves, she also uncovers the history of the women and the people’s history. Her methods are distinctly cultural. Belcourt’s research for the book 4 Beadwork: First Peoples' Beading History and Techniques is an example of this. As the title suggests, the book explores the history of beadwork, materials, techniques, and applications embedded within the cultural and spiritual significance of First Nations culture. These techniques include active listening, observation, practice and presence. These teachings are shared in a traditional relationship such as learning a skill from a grandmother, auntie, or a community of women. As both a theoretical and literal grounding in her paintings, Belcourt has found a way to weave a complex of systems and relationships into her art using Metis historical beadwork. This is illustrated in the following two images. In Figure I, a partial image of a historical Métis beadwork piece is shown. It is a beaded hide pillow or pad for a saddle which is usually stuffed with deer hair and held in place with a girth strap, circa 1870.We know this is an example of traditional Métis beadwork because one of its characteristics are the colours of the flowers which are embroidered in shades of pink to red, with buds in shades of blue and purple. The flower centres were white or dark yellow and the leaves green. Most important to the historical design is the focal centre of the flowers. The second work, Figure 2, is a piece from Belcourt’s series called Great Métis of Our Time (2006). Along the sides of one of the portraits—the portrait of Jean Teillet, who was the great-grand niece of Louis Riel- Belcourt, has painted traditional-style Métis beadwork designs. By placing traditional Métis designs symmetrically on both sides of the portrait, Belcourt is acknowledging the past artistic contributions of Métis women's beading as an essential part of the well being of Métis people. At the same time, she is portraying a contemporary individual whose determination to seek justice for Métis rights has changed the course of history for the Métis Nation in modern times. 5 In my own research for this paper, I learned that the trailing flower designs became the indicator of Métis handicraft. As with Belcourt’s process, the origin of the Métis beadwork designs came from methods of experimentation and the merging of various art traditions. The use of floral design, which is now strongly associated with the Métis, actually originated from the quillwork traditions practiced before the 1840s and later the introduction of embroidery from contact with the Roman Catholic Mission. As Belcourt continues her research and practices, her exploration is extending and evolving into an awareness of the medicinal qualities of the plants themselves traditional knowledge. Increasingly in her personal life, she is gathering and harvesting plants for medicinal purposes with her fiancé who is a Traditional Medicine Person. Belcourt makes connections across boundaries and disciplines using interdisciplinary methods such as referencing her Metis ancestral history, active listening with traditional elders, and the gathering of scientific information. Through these methods she gains knowledge of the many therapeutic properties of the plants which she includes in her paintings. Some of the traditional medicines she includes in her work are berries, which are considered women’s medicine. Strawberries, raspberries, chokecherries, blueberries—each one arrives at a certain time and each has many teachings. In the calendar, N'ginaajiw—My Spirit is Beautiful, Self-Esteem Awareness Campaign for First Nations Women, the 'berries' are highlighted from the months of June to September. This calendar shares women's moon teachings. For example, June is known as the sixth moon of Creation, which is the Strawberry Moon. One of the teachings of the strawberry is included in the calendar as it relates to self-esteem. “The medicine of the strawberry is reconciliation. It was during this moon cycle that 6 communities usually held their annual feasts, welcoming everyone home, regardless of their differences, over the past year, letting go of judgment and/or self-righteousness.”3 There are many teachings that can be shared from one object. For example, I remember sitting in a circle at New Credit Powwow in 2004. The Elder asked everyone to share one teaching they knew of the strawberry. One person spoke of the seeds representing the future of the unborn children. Another person spoke of the green top as medicine and it was good to eat because most of the health benefits were there. Another person spoke of how when you cut into the strawberry, it reveals the shape of a heart. From her studies of the diversity and complexity of Native plants in her area, Belcourt has been continuously educating herself concerning the many different aspects of biodiversity, with a particular emphasis on the subject of the interdependency of all life on the planet. With her work, she illustrates how our existence is intricately interwoven with the existence of all other species on this planet. CREE NARRATIVE MEMORY “Stories hold the echo of generational experience.”4 First Nations and Métis cultures are oral cultures. Cree oral stories form a narrative memory of how we as Native peoples came to be, how our ancestors interpreted the world, how they lived, and how that narrative memory continues to be retold, offering us guidance and renewal for today. Despite centuries of colonial intervention and attempts at either assimilation or genocide, the original languages, which were of Being, have kept alive the essence of narrative memory as interrelationship through a time that 3 N'ginaajiw—My Spirit is Beautiful, Self-Esteem Awareness Campaign for First Nations Women, sponsored by Union of Ontario Indians/Anishinabek Nation, Association of Iroquois and Allied Indians. North Bay, Ontario, 2005. 4 McCloud, Cree Narrative Memory, 1. 7 has no beginning or end. In Indigenous languages, “There is no Word for Time,” as in the title of Evan T. Pritchard’s book on the Algonquin people: "They don't write in metaphor, they speak it; they don't recite poetry, they live it."5 The importance of a narrative memory is an essential element in the work of both Belcourt and myself. As McLeod states in Cree Narrative Memory, “the importance of our ancestors is that if my great grand mother did not exist I would not exist.”6 As Indigenous Cree Women artists, our artistic language is a distinct language formed by our experiences with the land and our communities. Our stories, which are inside of us, around us, and through us remind us of who we are. MERGING TRADITIONS AND TECHNOLOGIES As visual artists of a Cree-Métis background, both Christi and I speak from the support and knowledge of our known traditional ancestries and our blood memories. In Belcourt’s early work she began by placing a few ‘dots’ within her paintings to suggest beadwork. Her process has now developed to where entire floral patterns are created in dots by dipping the end of a paintbrush or knitting needle into the paint and pressing it onto canvas. The effect is thousands of raised dots per canvas that simulate and look like beadwork. From our interview, Christi explains how her personal artistic ‘language’ and work began to evolve when she moved to Whitefish Falls in 2004 ‘where she now lives’: ‘Moving away from the city allowed me the freedom to study plants, and to get to know the land on my own schedule… Close to the land I'm focused, I'm relaxed - Pritchard, Evan, No Word for Time The Way of the Algonquin People, Coucnil Oak Books, LLC, San Francicso, CA, Tulsa, OK, 1997 6 McCloud, Cree Narrative Memory, 8. 5 8 I've totally changed, and my art has benefited in every way imaginable because of it.” An integral part of Belcourt’s evolving personal artistic language is a return to the land and into the spiritual traditions and practices of her people that honour balance, relationships, and healing. In our interview, she shared her practice of offering tobacco, one of the four traditional medicines, whether it is in the field or in her daily painting practice. The offering of tobacco is a First Nations relationship practice of honouring the language of our deep connection with every living being on this planet in a humble and respectful way. She explained how she greets the plants as brother or sister, and in essence, she is thanking them for what they are choosing to give her so that she may help others. In her daily studio practice she smudges herself, her paints, and her work with medicines and says a prayer asking her helpers to assist with colours and for the patience to do her work well and skillfully. She also asks that her paintings will bring about good feelings in those who view it. She requests that her work can help people to connect with their own spiritual selves and with the spirits that live in everything all around us. In closing, she thoughtfully makes an appeal that her paintings will help people and will inspire them to be kind and loving towards the earth, all living things and each other. First Nations people believe when we are making something we are like the Creator, so it is important to have good thoughts, for everything that is made has a spirit. Through the interview process between Christi and myself, I was able to retrieve meaningful information about her reality as a First Nations female artist. 9 In the last few years, Belcourt has begun creating larger works, Figure 3 where larger themes are visible. I asked her about this. Belcourt says she is motivated by what would be characterized as political aims. The paintings by their size alone cannot be overlooked or ignored. It is through the large works that she brings forward an awareness of the beauty and resilience of her culture that can no longer be disregarded. Winona Laduke, an Indigenous ‘activist’ scholar, in her book, Recovering the Sacred, explores the passing of history and knowledge from one generation to the next in a similar way that Belcourt’s work celebrates the past contributions of the Metis in Canada through the process of bringing forward the colourful beadwork of her culture.7 When all First Nations were facing an onslaught of oppressive governmental policies during the early and middle 19th century, the colorful beadwork of the Métis represented defiance in the face of genocidal strategies. The colorful beadwork art form became and continues to be a bold, bright, evident gesture of the Métis to remain highly visible. Just as in Belcourt’s large works, the highly decorative clothing, including numerous items used in everyday life, proclaims the same visual cultural message: As Métis, we will not be ignored. CONCLUSION In conclusion, I have come to understand Belcourt’s artistic research methods are an ongoing process of observation and self-discovery which inform her studio practice investigations. The utilization of these many methods have provided her with the choices to shape and convey a shifting canvas of contemporary forms of memories across disciplines of Métis history and First Nations women’s traditions. 7 Winona Laduke, Recovering the Sacred the Power of Naming and Claiming (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2005). 10 What successfully distinguishes both our art practices is the honouring of our cultural traditions through methods which affirm the validity and strength of our traditions. Our use of materials and themes illustrate aspects of our Cree/Métis cultures in a contemporary context that reflects and celebrates our realities as First Nations women. Most importantly, I discovered that what are new understandings of research methods are also old processes of traditional Cree-Metis practice: processes that are unfolding as acts of remembering and reclaiming. 11 Bibliography Belcourt. Christi. “Purpose in Art, Métis Identity, and Moving Beyond the Self.” Native Studies Review 17, no. 2 (2008): 143-153. Laduke, Winona. Recovering the Sacred the Power of Naming and Claiming. Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2005. Luker, Kristen. Salsa Dancing into the Social Sciences Research in an Age of Info Glut. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008. McLeod, Neal. Cree Narrative Memory from Treaties to Contemporary Times. Saskatoon, Saskatchewan: Purich Publishing Limited, 2007. Sullivan, Graeme. Art Practice as Research Inquiry in Visual Arts. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2005. Young, David, Grant Ingram, and Lise Swartz. Cry of the Eagle: Encounters with a Cree Healer. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1989. 12