parts unknown-doc

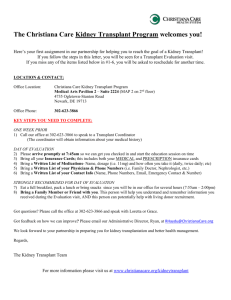

advertisement