animal

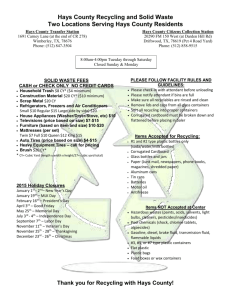

advertisement

Des Moines Register 05-17-06 Animal disease lab violating air-quality rules The state lists 21 offenses but a center spokeswoman says pathogens were not present in emissions. By PERRY BEEMAN REGISTER STAFF WRITER The National Animal Disease Center in Ames has violated state air-quality rules nearly two dozen times since April 2004 and faces a $10,000 fine for offenses that include excess emissions from incinerators. The Iowa Department of Natural Resources also has cited the lab - a federal research facility known for its testing of mad cow disease - for loading too much waste into the incinerators, failing to record how much waste was burned, neglecting to monitor certain pollutants, and building without a construction permit. Sandy Miller Hays, a lab spokeswoman, said the brief episodes when the plant emitted too much smoke — some of them lasting only a few minutes — may have posed a threat to asthmatics, for example, but did not mean anyone was exposed to diseases. "It's not good for people to breathe smoke, but the incineration deactivates all prions," which transmit mad cow and chronic wasting disease, she said. Other pathogens are killed. "There is no infectious waste in our smoke," Hays said. "Incineration simply is going to kill everything." Jim Stricker, a state environmental protection worker, said the presence of smoke means combustion was incomplete. Doug Campbell, a state air-quality worker, said the state doesn't regulate pathogens from smokestacks, but added: "You could infer that if there is some kind of problem with the functions, something could be escaping. But we can't determine that." The lab burns all animal parts at 1,400 degrees Fahrenheit. Then the air from that process is burned at 1,800 degrees. Even if the process sends up smoke for short periods, Hays said, the temperatures would stop any threat of disease. Lab officials told the state that any problems have been fixed. Two employees recently questioned how the lab treats feces and urine from the facility before they are sent to the city's sewage plant, prompting a federal investigation and a news conference in Ames last week. Officials from the city of Ames and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which runs the lab, said that all such wastes are heat-treated and that there is no health risk to residents. Hays said those wastes are heated at 250 degrees for 30 minutes; studies have shown more than 99.9 percent of the material is destroyed in one minute. City officials didn't mention the air-quality problems last week. A check of state records found the violation and the state resources department's proposal to fine the lab $10,000. The department also would agree not to prosecute the lab further if federal officials agree to comply with state and federal air-quality laws. Hays said that the state makes 21 allegations in the proposed agreement, and that the lab refutes 15. Lab officials plan to meet with state lawyers next week to negotiate an agreement. "The Iowa Department of Natural Resources has documented numerous violations of Iowa's air-quality statutes and rules" at the lab, department attorney Carrie Schoenebaum wrote in a letter to the lab. Ames, a city of 51,000, has been home to the lab since 1961. In addition, 28,800 vehicles pass the 13th Street interchange with Interstate Highway 35, which is just east of the lab. Retired ISU engineering professor William Brockman, 68, said no one should worry until the facts are in. "The viruses, I think, are probably controllable, the prions are less so. I think they are very difficult to destroy. If they are simply being released, I think it could be a problem, not so for much public health, but maybe for the animal welfare in the state, agriculture and so on. If there are problems, I'm sure they will take care of them." Ames resident Katie Mead, a 25-year-old massage therapist, said she doesn't know enough to judge whether or not there is a problem. "I've just heard about the waste in the water so far, and I haven't heard anything about the smokestacks at all until just now. You know we also burn our trash, and we seem to be doing fine." Tom Newton, who supervises the environmental health division of the state health department, said the only risk posed by the smoky emissions would be the worsening of asthma or other respiratory problems. "From an infectious standpoint, it would be highly unlikely that they could transmit diseases through the stacks," Newton said. The state uses smoke emissions as a measure of problems with plant operations, said Brian Button, a spokesman for the resources department. "It's obvious that there should be a concern if something infectious is incompletely combusted," Button said. State records show that the lab is one of the smallest polluters among the large facilities that need state operating permits. In 2004, the lab emitted 48 tons of regulated pollutants, ranking 208th out of 297 facilities. The largest, a power plant at Sergeant Bluff, sent 48,394 tons into the air. Records show a pattern of problems. For example, in an April 6, 2005, notice of violation, state environmental inspector Bill Gross wrote: "The operational control of the incinerators needs improvement." Some of the offenses were reported by lab workers, as required by law, but some were reported later than required. Other infractions were turned up by state inspectors. In February of this year, an incinerator operator was found to be working with a certification that expired in June 2000. Federal officials told the state the man had taken the required courses, and would make sure his certification was renewed. Hays declined to comment.