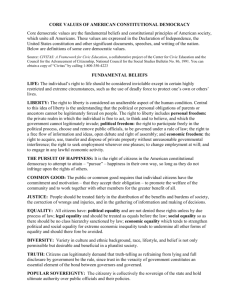

Due Process Good

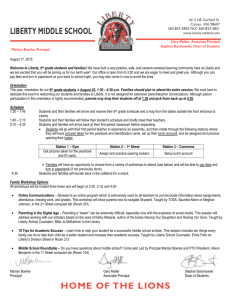

advertisement