Chapter Four: Evaluating arguments

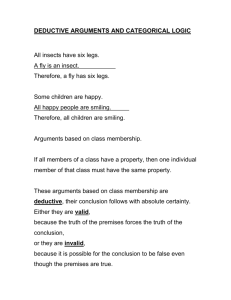

advertisement

Evaluating arguments Opinions vs arguments An opinion is a claim about something. When reasons are added to the claim, the combination of claim and reasons becomes an argument. Arguments are more effective in convincing people about something than are mere opinions. Arguments are made up of premises and conclusions, which can usually be recognized by identifying premise indicators (e.g., "because") or conclusion indicators (e.g., "therefore"). Formal and informal arguments Arguments are, in essence, conditional statements that have the form IF premises, THEN conclusion. The type and quality of the premises in an argument directly affect how convincing the argument is. Formal arguments are more convincing that informal arguments. Formal arguments are logically complete arguments (also called deductive arguments). That means that the premises provided in a formal argument lead directly to the claim being made (the conclusion). In other words, in a formal argument, if the premises (also called the antecedent of the conditional statement) are stated and found reasonable, then the conclusion (also called the consequent of the conditional statement) must unavoidably be deemed acceptable. Informal arguments are not logically complete. Logical form Formal arguments follow a predictable pattern composed of a major premise followed by a minor premise and ending with a conclusion. The major premise is usually an if/then statement that makes a claim about some truth in general, e.g., "if something has wings, then it flies." The minor premise that follows makes a claim about a specific instance, e.g., "butterflies have wings." Stated together, the major and minor premise inevitably call up the conclusion, e.g., "butterflies fly." This connection between the premises and the conclusion of a formal argument is called logical entailment. Only formal deductive arguments can be adequately evaluated. That is because the combination of major and minor premises they contain is intended to be adequate evidence for the conclusion. Informal arguments do not contain adequate support. 1 Enthymemes Many informal arguments have just a major premise or just a minor premise. Such informal arguments can be made into formal arguments rather easily by supplying whichever premise is missing. These arguments are called enthymemes. An example of an enthymeme is the statement "There must be a fire here because I smell smoke." The one premise ("I smell smoke") is a minor premise, as it makes a specific claim about a specific instance. Adding the general rule (a major premise) that "If there is smoke, then there is fire" makes the argument a complete formal argument: "If there is smoke, then there is fire. There indeed is smoke. (I smell smoke.) Thus there must be a fire." A second example of an enthymeme might be "The theory of evolution is unacceptable because I don't believe that humans evolved from apes." The unstated major premise is "If the theory of evolution is accepted, then one must believe that humans evolved from apes." The completed formal argument is then "If the theory of evolution is accepted, then one must believe that humans evolved from apes. I don't believe that humans evolved from apes. So the theory of evolution cannot be accepted." A third example of an enthymeme might be "Extramarital sex is wrong because if a practice breaks up marriages, then it is wrong." The unstated minor premise is "Extramarital sex breaks up marriages." The completed formal argument is then "If a practice breaks up marriages, then it is wrong. Extramarital sex breaks up marriages. So extramarital sex is wrong." Specifically stating the missing but assumed premise of an enthymeme allows critical thinkers to evaluate the adequacy of both premises. Validity Formal arguments can be evaluated. An acceptable argument is called a sound argument. To determine if an argument is good or sound, analyze two things: o the logical form of the argument (the argument's validity) o the reasonableness of its premises, i.e., whether the premises are probable and relevant to the conclusion. If either test fails, the argument is not sound. A valid deductive argument has premises that (if we assume they pass the test of acceptability) lead unerringly to the conclusion. IF acceptable premises, THEN acceptable conclusion. Reducing an argument to its logical form is called symbolizing the argument by identifying is propositions and logical connectives and substituting letters or symbols for those elements. 2 There are three valid logical forms (that we study in this course): o Modus Ponens: If p then q; p; hence q. o Modus Tollens: If p then q; not q; hence not p. o Disjunctive Syllogism: p or q; not p; hence q. Just as there are forms of rational thinking (e.g., rationalization, weaksense critical thinking, and instrumental reasoning) that resemble critical thinking but are not critical thinking, so too there are logical forms of deductive arguments that resemble valid forms but are invalid. Two examples of such invalid argument forms follow. If p then q; q; hence p. (the fallacy of affirming the consequent) If p then q; not p; hence q. (the fallacy of denying the antecedent) Implications Having evaluated the validity of an argument, we know that o if an argument has a valid logical form, then its conclusion must necessarily be accepted (if the premises are also determined to be reasonable). o if an argument has an invalid logical form, then its conclusion does not necessarily have to be accepted (even if the premises are determined to be reasonable). o if an argument has a valid form but the conclusion is known to be false or questionable, then at least one of the premises must not be reasonable. Evaluating arguments is easier when we have a model or standard against which to measure their worth. 3