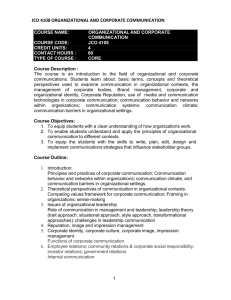

Corporate citizenship and reputational value

advertisement

CORPORATE CITIZENSHIP AND REPUTATIONAL VALUE Caz Batson Hawke Institute University of South Australia St Bernard’s Road Magill SA 5072 Australia Ph: 61 8 8302 4371 Email: carol.batson@unisa.edu.au In his influential book “Reputation: Realizing Value from the Corporate Image”, Charles Fombrun (1996) asserted that the reputation of a corporation is nothing more nor less than an aggregation of the perceptions, or cognitions, that people hold about its credibility, its reliability, its responsibility and its trustworthiness. In this context, he proposed the following operational definition of corporate reputation: “…A corporate reputation is a perceptual representation of a company’s past actions and future prospects that describes the firm’s overall appeal to all of its constituents when compared with other leading rivals..." (p.72) More recently, Fombrun, Gardberg and Barnett (2000, p.88) have argued that corporate citizenship “is an integral component of a cycle through which companies generate reputational capital (conceptualised by Frombrun as the value of intangible assets excluding intellectual capital), manage reputational risk and enhance performance”. The idea that pro-active, strategic engagement in corporate citizenship will deliver benefits to the bottom line is, of course, not new. The problem, however, is that there is presently a paucity of empirical evidence to either substantiate or refute this claim and, in the absence of this, the apparent reluctance of many Australian organisations to jump on the ‘corporate citizenship bandwagon’ can perhaps be justified. Fortunately, the scope of empirical research now appears to be widening, as recently evidenced in the work of King and Mackinnon (2000, 2001) here in Australia and that of Maignan and Ferrell (2000, 2001) overseas. These researchers who, respectively, have investigated differences in community and consumer perceptions of corporate citizenship, have also sought to measure stakeholders’ intentions to support socially responsible organisations. Such research, I would suggest, paves the way to a more comprehensive understanding of the multi-dimensional nature of corporate citizenship and a more critical exploration of the differential value various stakeholder groups may accord to related practices. The ‘Corporate Citizenship and Reputational Value’ Project The ‘Corporate Citizenship and Reputational Value’ Project was formally established in the University of South Australia’s Hawke Institute of Social 1 Research in late 1999 in partnership with the National Heart Foundation of Australia. Stage 1 of the project, undertaken by Dr Debra King in collaboration with Professor Alison Mackinnon, concluded some 12 months later. Stage 2 commenced in June 2001 with funds made available by the Hawke Institute itself. When the prospect of a partnership with the National Heart Foundation of Australia was first discussed, the mutual point of interest was to find ways to encourage the take-up of corporate citizenship practices by Australian organisations. It was recognised, in this context, that corporate citizenship could be more effectively marketed if the nature of related practices, and their potential to impact both reputation and the economic value of reputation, was better understood. Our central research hypothesis was thus cast in simple terms – “that adopting corporate citizenship practices influences the value of a corporation’s reputation” – and the following aims were established to guide the investigation: 1. To examine the extent to which corporate citizenship influences stakeholder perceptions regarding the reputation of corporations. 2. To examine the extent to which stakeholder perceptions regarding reputation influences stakeholder behaviour. 3. To identify the attributes or factors that influence corporate reputation. 4. To develop a mechanism for measuring and comparing corporate reputation. The Research Framework Community participation in corporate citizenship research has previously occurred at the macro level, where perceptions regarding the roles and responsibilities of business have formed the primary focus (cf. Clemenger, 1998; Environics, 2000) and the micro level, where the performance and practices of individual organisations has attracted attention. Positioned between the macro and micro levels, however, is another level of analysis, the mesa level, which my colleagues judged could provide a new and valuable opportunity to further investigate the nature of corporate citizenship and its relationship to reputation and reputational value.1 More specifically, having chosen to work at the mesa-level, King and Mackinnon were able to measure the extent to which community members – conceptualised as ‘potential stakeholders’ - valued certain aspects of corporate citizenship over King and Mackinnon (2001) have argued that Fombrun’s (1996) concept of ‘reputational capital’ covers the value of intangibles that may or may not relate to reputation. In view of this, they utilised the concept of ‘intentions to deal’ (eg. use product or services, invest in, work for) as an indicator of reputational value. 1 2 others.2 They were also well placed to examine the influence of demographic and/ or stakeholder group variables on perceptions and intentions to deal. ‘The Responsibilities of Business in Society’ Survey The central feature of the survey mailed out to 2,200 randomly selected households across Australia in March 2000 was an inventory of 40 corporate citizenship practices derived from an extensive review of the corporate social responsibility literature and an ‘expert’ consultation process.3 The practices were grouped into the broad categories of ‘Community’, ‘Management’, Workplace’ and ‘Environment’ and the majority were then further classified into sub-categories (see Figure 1). The order in which the various practices appeared in the survey instrument was, however, randomly selected. Figure 1: The hierarchical relationships among the sub-scales of the Corporate Citizenship Scale CORPORATE CITIZENSHIP REPUTATION INTENTION TO DEAL ((40) Subset Community Involvement (5) Sponsorship (4) Development (4) Community Management Governance (5) Ethics (4) Marketing (5) Management Workplace Employees (6) Human Rights (2) Environment General (5) Workplace Environment The term ‘potential stakeholders’ was employed to draw a conceptual distinction between community members who are actual stakeholders in various corporations and those who have the potential to become stakeholders based on their perceptions of any corporation’s practices and performance. 3 The response rate of useable surveys was 13.7% (274). Although low, this rate was considered reasonable in view of the unsolicited and very specific nature of the survey. The sample size has proved adequate for all statistical analyses undertaken in the project to date. 2 3 For each corporate citizenship practice listed in the inventory, responses to two questions about a hypothetical corporation were sought: 1. To what extent would knowing about this aspect of corporate behaviour influence what you think about the corporation’s reputation? 2. To what extent would knowing about this aspect of corporate behaviour influence your decision to deal (use products/ services, invest in, work for) with this business in the future? The 5-point Likert scales attached to each item ranged from -2 (decrease reputation/ dealings a lot) through 0 (no change) to +2 (increase reputation/ dealings a lot). In addition, survey respondents were asked to: Identify the circumstances in which a corporation’s financial or social performance would hold importance for them Evaluate the capacity of various stakeholder groups to influence corporate behaviour Rank key attributes of corporate reputation Provide demographic and stakeholder group membership data Outcomes of the Research The data obtained from the national survey has been and, indeed, continues to be subjected to rigorous statistical analyses. Whilst it is beyond the scope of the present paper to discuss these in any detail, key features of statistical treatments and outcomes are highlighted below. The Corporate Citizenship Scale Through Rasch scaling, the coherence of the proposed Corporate Reputation and Future Dealings Intentions scales and all other scales in the Corporate Citizenship instrument was first established. A total of 3 items were removed from the instrument in the process. Two statistical techniques were then employed to examine the relationship between corporate behaviour, stakeholders’ perceptions of reputation and their intentions to deal in light of these. First, the correlations between the various reputation and intention to deal scales were determined and all were found to be high and highly significant (p<<.000). Accepting that there are reasonable theoretical grounds for arguing a causal relationship, the correlation values suggest that between 66 – 77% of the variation evident in intentions to deal can be explained by changes in reputation perceptions. Second, a path model of the relationship between reputation and intentions to deal was developed and tested (see Figure 2) and, consistent with the first analysis, the results indicated that 76% of the variation in intentions to deal could be explained by changes in reputation perceptions. As well, the path analysis results provided 4 some evidence that community stakeholders ascribe equal importance to the four broad corporate citizenship categories. Figure 2: Generalised path model of the relationship between reputation and intentions to deal. Community ITD Community REP Management ITD Management REP REPUTATION INTENTION TO DEAL Workplace ITD Workplace REP Environment REP .858 3 Environment ITD In summary, then, the results of the initial analyses confirmed that 37 of the 40 original items used in the Corporate Citizenship instrument formed a coherent scale that exhibited good psychometric properties and could thus be replicated with confidence for use in other settings and with other stakeholder sample groups. As illustrated in Figure 3, the 37-item Corporate Citizenship instrument yields two weighted scores for each corporate behaviour. The first score (top bar) provides a measure of the change in reputation perceptions that might be expected to occur if an organisation adopted the practice in question; the second score provides a measure of change in intentions to deal. The scale thus supports comparative analyses of the extent to which corporate behaviours in the citizenship domain are likely to influence reputation and reputational value. On the basis of the national survey results, for example, the five corporate citizenship activities most likely to exert a positive influence on reputation and intentions to deal are: W2 Retrain employees to avoid redundancies (REP=394; ITD=330) C1 Assist in the development of employment programs for the unemployed in a local region (REP=389; ITD=333) E2 Focus on increasing the use of recyclable materials in manufacturing processes (REP=386; ITD=325) E3 Become industry leaders in developing environmentally sustainable business practices (REP=376; ITD=328) C2 Subsidise and maintain its services to rural communities (REP=365; ITD=308) 5 Activities that will exert a negative influence on reputation and intentions to deal, denoted with an asterisk (*) in Figure 3, can also be readily identified: W1 Employ children under 10 years old in offshore factories (REP=506; ITD=480) E1 Disregard scientific evidence indicating that the corporation is polluting a major water source (REP=498; ITD=480) M1 Disregard evidence that there could be safety implications for customers using one of its products (REP=437; ITD=430) M2 Sell its customer list to an advertising company (REP=407; ITD=383) M3 Decrease the quality of its products to retain its price competitiveness (REP=362; ITD=354) Having noted before that the 37-item Corporate Citizenship instrument has good psychometric properties and can thus be replicated with confidence, we have nonetheless worked over the past year to refine it and to also identify a subset of items as the basis for a short form of the instrument. In so doing, we have restricted our attention in the second stage of the project to the Corporate Reputation scale. The Factor Structure of the Corporate Reputation Scale Bearing in mind King and Mackinnon’s (2000, 2001) premise that four categories of corporate citizenship influence people’s overall perception of corporate reputation, confirmation of the factor structure of the Corporate Reputation scale was obviously required. To accomplish this, three hypotheses representing theoretically important alternatives were initially tested using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and the original 40 corporate reputation practice items. The alternative models, presented diagrammatically in Figure 4, were as follows: A A one factor model which, if shown to be the best fitting model, would indicate that King and Mackinnon’s hypothesised subscales do not form constructs that can be usefully differentiated from a single, overall Corporate Reputation construct. B A model comprising four discrete but correlated constructs (Community Reputation, Management Reputation, Workplace Reputation, Environmental Reputation) that do not necessarily combine to reflect a single, overall Corporate Reputation construct (ie. are not subordinate). C Consistent with King and Mackinnon’s conceptualisation, a hierarchical four-factor model in which the four separate 8 constructs listed above in B reflect a single underlying Corporate Reputation construct. Figure 4: Three alternative models of the factor structure of the corporate Reputation Scale. Item 1 Item 1 Item 2 Item 3 Item 2 ComRep Item 1 Item 2 Item 3 ComRep Item 4 Item 4 Item 4 ManRep CorpRep ManRep Item 20 Item 20 Item 21 Item 21 WorkRep Item 20 CorpRep WorkRep EnvRep Item 38 A EnvRep Item 39 Item 40 Item 40 Item 21 Item 38 Item 39 Item 38 Item 39 B Item 3 Item 40 C The fit statistics calculated in respect of the three models indicated that model A was not well supported by the data and that although models B and C were both somewhat better supported, their fit was certainly less than expected. With the adequacy of the sample size not at issue, it was evident that some refinement of the instrument was needed to achieve better model fit. Efforts to refine the Corporate Reputation scale have now also led to the development of a 20-item version (CR20). This has been found to have excellent fit characteristics and the data obtained in respect of it support King and Mackinnon’s hypothesised instrument structure – an overall Corporate Reputation scale with four subordinate scales. It is also noteworthy that although certain demographic and stakeholder variables were found to exert a modest influence on sub-scales of the CR20, none were strong enough to pose a threat to the measurement validity of the short form. In their current forms, both the short and long versions of the Corporate Citizenship Scale pose generic questions about a hypothetical organisation – and some of these still need to be tightened up to force respondents to make harder choices. This said, the theoretical and analytical steps we have taken in the course of our research clearly point to the fact that the scale can be modified or extended – with integrity – for use in different settings and with a variety of stakeholder groups. If the purpose is to gain specific information about an organisation or sector, for example, scale items can be edited to reflect relevant practices and parallel forms can be used to tap respondents’ actual knowledge as well as their views. Equally, the scale can be used to gauge, target, build and monitor stakeholder support and to inform the development and implementation of internal and external corporate citizenship strategies and related communications. 9 Conclusion To conclude, then, the research undertaken by the Hawke Institute empirically supports Fombrun, Gardberg and Barnett’s (2000) assertion that ‘good’ corporate citizenship positively influences reputation and the economic value of reputation. Recognising the controversy surrounding the concept of corporate citizenship itself, and the means by which its influence might best be measured, we developed a comprehensive instrument that was firmly grounded in theory and which introduced the behaviour-based concept of ‘intentions to deal’ as a new measure of reputational value. Using data derived from a national survey of ‘potential’ stakeholders, the Corporate Citizenship Scale has held up under very rigorous testing conditions and thus we can confidently attest to its utility. There remains, however, some scope to further improve the scale before it is made more widely available and we hope to complete this work in the near future. References Clemenger Report (1998) What Ordinary Australians think of Big Business and What Needs to change?, Sydney: Clemenger. Environics, 2000. The Millenium Poll on Corporate Social Responsibility: Executive Briefing, Toronto: Environics International. Fombrun, C. J. 1996. Reputation: Realizing value from the corporate image. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. Fombrun, C. J., Gardberg, N. A. & Barnett, M. L. 2000. Opportunity platforms and safety nets: Corporate citizenship and reputational risk. Business and Society Review, 105, 1, 85 – 106. King, D. & Mackinnon, A. 2000. Corporate citizenship and reputational Value: The marketing of corporate citizenship, Magill, Australia: Hawke Institute, University of South Australia. King, D. & Mackinnon, A. 2001. Who cares? Community perceptions in the marketing of corporate citizenship. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, Autumn, 37 – 53. Maignan, I. 2001. Consumers’ perceptions of corporate social responsibilities: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Business Ethics, 30, 57 – 72. Maignan, I. & Ferrell, O.C. 2000. Measuring corporate citizenship in two countries: The case of the United States and France, Journal of Business Ethics, 23, 283 – 297. 10