Managing the Sefton Dunes

advertisement

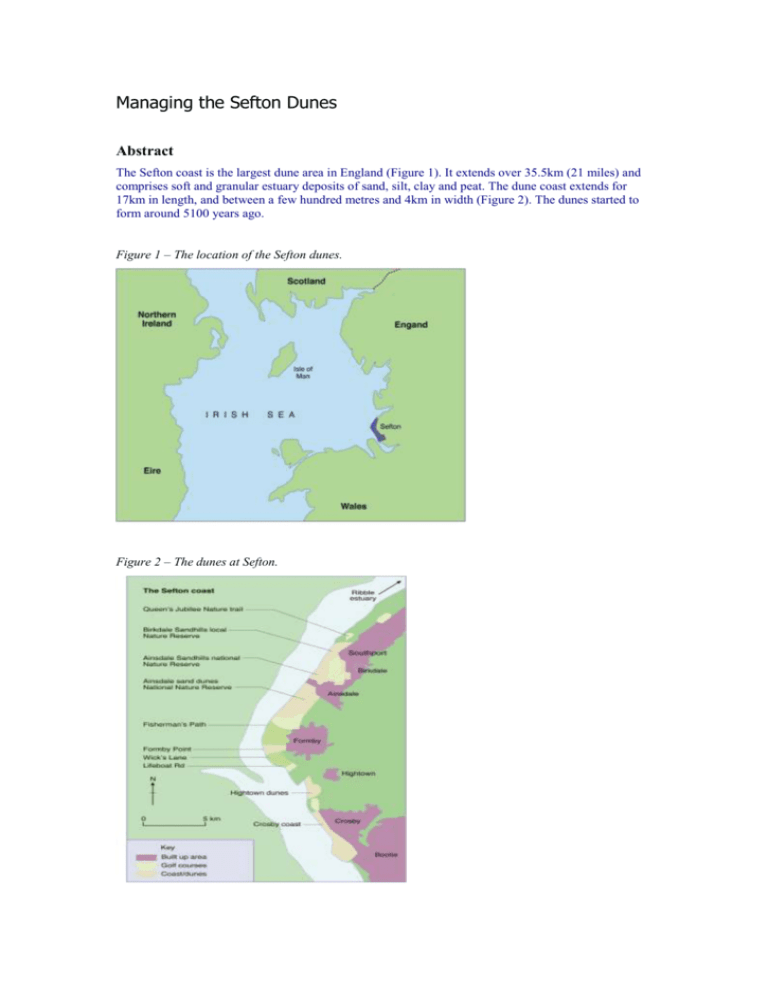

Managing the Sefton Dunes Abstract The Sefton coast is the largest dune area in England (Figure 1). It extends over 35.5km (21 miles) and comprises soft and granular estuary deposits of sand, silt, clay and peat. The dune coast extends for 17km in length, and between a few hundred metres and 4km in width (Figure 2). The dunes started to form around 5100 years ago. Figure 1 – The location of the Sefton dunes. Figure 2 – The dunes at Sefton. Early management and sand dune development Human intervention has constrained the natural development of the Sefton coast for centuries. Attempts at stabilising the Sefton dunes began in the early eighteenth century. Erosion continues to be a problem in the Formby area and there have been different attempts at stabilising the dunes. Not all of these have been successful and some have created new problems. Overall, the Sefton coastline is becoming straighter. The erosion of Formby Point is causing major coastline straightening as dune material is deposited on the frontages to the north and south. Part of the Crosby and Southport shoreline has been partially fixed by coastal defence work. However, the natural forces remain at work and sand drift at Crosby is tending to bury parts of the sea wall, whilst sand dunes are developing in front of the sea wall north of Weld Road, Birkdale, near Southport. However, between Hightown and Birkdale the coastline is in a more natural condition, with generally wide sandy beaches still backed by an extensive system of sand dunes. The Sefton coast has to be considered in the light of the effect of possible climatic change, i.e. global warming, sea-level rise and an increase in storminess. Recent climate modelling work suggests a possible rise in average sea level of 0.3m over the next 60 years. On top of this, the increase in maximum wave height and meteorological surge effects on any storm event must be considered. Succession on sand dunes Sand dunes are one of the most dynamic environments in physical geography. Important changes take place in a very short space of time. On the beach, conditions are very windy, dry (most of the water just soaks into the sand) and salty, and few plants can survive these extreme conditions. However, two plants that can survive in this environment are sea couch and marram grass. These have adapted to tolerate water with a high salt content, high wind speeds, and burial by sand. In fact, marram grass needs to be buried by fresh sand in order to send out fresh shoots. Once marram grass and sea couch are established on the beach, they reduce the wind speed and this helps trap fresh sand. As the sand builds up, the marram grass and sea couch send out new shoots, trapping more sand and building up a dune. The presence of marram grass and sea couch in the sand dune increasingly adds organic matter and moisture to the sand dune and this allows other plants to grow. The growth of new plants is called succession. The second tier of plants cannot tolerate the dry, windy, salty conditions of the beach but can survive in the less windy, moister, less salty dunes. They in turn alter the environment so that other species can invade and develop. On a sand dune over a distance of just a few hundred metres there may be as many as four or five different types of ecosystems (Figure 3). Figure 3 – Succession at Ainsdale. Soil pH % of bare ground Number of plant species Main plant frequency Shore/foredune Unconsolidated sand with shelly fragments; no organic content; no water retention. Mobile dune Sand with traces of humic material; fewer shells than on the shore; no water retention. Fixed dune Brown surface humic layer 8cm deep overlying sand; no visible shells; some water retention. 8 100 8 85 5 10 Dune heath Black humus-rich surface layer 30cm deep; water retentive; overlying light grey layer 10cm deep, overlying orange sand. 4 0 1 Seaward 5, leeside 15 Marram 90%, red fescue 85% 27 12 Sand sedge 75%, Yorkshire fog and other grasses 70%, marram Ling heather 90%, gorse 10%, heath rush 30% Sea couch 1% Main animal species Visitors, e.g. gulls, oyster catchers Skylark, ringed plover, common lizard 60%, red fescue 60%, creeping willow 60%, dewberry 55% Six spot burnett moth, Shelduck meadow pipit, sand lizard Wood mouse, field vole, common shrew, rabbit, kestrel As a result of succession, the Altcar sand dunes and the dunes to the north of Ainsdale Sand Dunes National Nature Reserve are now moving out towards the sea. Elsewhere, deposition of sand begins about a kilometre north of Ainsdale National Nature Reserve and remains the dominant trend at Southport and within the Ribble Estuary. Erosion of the Formby dunes As there are no rock outcrops on the shoreline at Formby to shelter it from the influences of the wind, water and human activity, the shoreline is constantly changing. For example, extensive erosion at Formby Point during the eighteenth century was reversed in the mid-nineteenth century, when it gained 300m around its whole arc. The local population at the time erected sand-trapping fences and planted marram grass in an effort to increase the size of the sand dune system. The twentieth century has once again seen extensive erosion at Formby Point, with almost all of the land gained in the nineteenth century being lost – approximately 700m of land was lost between 1920 and 1970. Storm-force winds and destructive waves in the late 1800s are thought to be the cause of this latest phase of erosion. Coupled with this was the reshaping of the seabed at Liverpool Bay, caused by, among other things, dredging, which led to increased wave action around Formby Point. Erosion now takes place over a 4km area between Lifeboat Road to the south of Formby Point and Fisherman’s Path to the north of Formby Point. The most rapid rates of erosion have been between Dale Slack Gutter and Fisherman’s Path, with more than 40m of erosion since 1981. Presently, erosion is greatest to the north of Wicks Lane and it particularly affects the National Trust property. In recent years the average rate of dune erosion at Formby shows a general relationship with the frequency of westerly storms. At Formby Point the rate of dune erosion is up to 5m each year, whereas within a few kilometres to the north and south there is rapid growth of the coast. Significant dune erosion occurs when major storms coincide with high tides. The soft, sandy coast can be badly affected by recreation. When visitor numbers swell during the holiday season, serious damage can be done. There is a need to balance people’s enjoyment of the coast with the need to protect the landscape. Present beach and dune management measures recognise the likelihood of storm damage. Where visitor pressures are high, it is acceptable to confine public movement to boardwalks and paths and to fence vulnerable areas. By the year 2050, the coastline is likely to erode by up to 270m along the Formby Golf Club frontage. This represents a total loss of 910,552 square metres of land. Because of the mobile nature of sand dunes, any attempt to ‘freeze’ it in position will fail. Moreover, any interference with the coastline at Formby is likely to have serious implications for other parts of the Sefton coast. Today, the erosion rate is greatest at the boundary between the National Trust site at Formby and the Ainsdale Sand Dunes National Nature Reserve, with an average loss of approximately 4.5m per year over the past 20 years (1999 figures). Individual erosion events often result in a short-term loss of several metres. These events are generally transitory and conditions then settle back into the long-term trends identified. Human impacts Human influences on the dunes, which include dredging, river training and coastline hardening, have imposed a pattern of accretion and erosion on the shoreline where previous conditions were much more variable. In more recent times the dunes have been partially stabilised by maintaining their natural vegetation. Pine trees have been planted (Figure 4), further stabilising the dunes, and artificial sea defences have been built to protect the developed shorelines. The inland lakes and mosses behind the belt of coastal dunes have been drained and claimed for agricultural production. Figure 4 – Pine tree planting to help stabilise the dunes. Impacts of recreation Recreation in the coastal zone takes many forms: walking (with and without dogs), jogging, horse riding, driving in 4WD vehicles, and ‘bucket and spade’ visitors. The Sefton coast has also seen landspeed record attempts, car races, motocross events, hovercraft trips and flying. During the 1960s and 1970s the coast was very popular with thousands of holidaymakers heading for the sea, often in an uncontrolled manner. As a result, the frontal dunes suffered. This was most pronounced around Formby Point, where by the early 1970s the frontal dunes were completely devastated. In response to this destruction the Sefton Coast Management Scheme was created to co-ordinate the management and subsequent recovery of the sites. Visitor access is now closely monitored and controlled to prevent this occurring again. The rapid popularisation of off-road vehicles also led to problems, as the dunes were an attractive challenge. The vehicles would break up the dunes and destroy the vegetation. Again, this is now managed correctly and no off-road vehicle use is allowed. At Birkdale, where the vehicles were stopped from entering in the early 1990s, a new marsh/dune ridge has rapidly accreted, suggesting that the vehicles had prevented the natural deposition of the coastline at this point. This new marsh helps protect the frontal dunes by reducing the energy of the waves that cross it. Plantations In the early 1900s, large areas of the Sefton dunes were covered with plantations of pines. This caused several problems. Firstly these plantations meant that there was a reduction in the dune habitat and associated species, and secondly woodland canopies block out much of the light so that other plants are unable able to grow. This resulted in the loss of many specialised sand-dune plants and animals. Another problem of the pine plantations is the needles they deposit on the surface. The needles are very acidic and therefore change the chemistry of the soil, as well as causing large accumulations of organic matter at the soil surface, as the needles take a long time to decompose. In the pine woodlands, the pine trees are often the only plant species present. However, there is resistance to allowing the dunes to return to their natural form, as the pine plantations have been colonised by red squirrels, now a protected species in Great Britain (Figure 5). The pine woodlands at the rear of the Sefton coast sand-dune system are therefore managed to maximise the conservation of the red squirrels. Figure 5 – Red squirrels, a major tourist attraction in the region and the reason why any removal of the pine woods is met with opposition. Other pressures Sand dunes do not operate as sea defences in the conventional sense. At Formby, there is insufficient sand to enable dune recovery after storms (Figure 6). There is some suggestion that the presence of woodland at the seaward edge of dunes not only prevents dune recovery from storm erosion, but can temporarily increase the erosion rate, as sand can easily be washed away from the roots by wave action and the trees pull up large areas of soil when they topple. Figure 6 – Erosion of the dunes at Formby. Sand was extracted commercially from many parts of the Sefton coast during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and continues today at the Horse Bank, Southport. Areas from which sand was removed included Crosby shore, Fort Crosby, Hightown shore and dunes, and Formby dunes. In 1966, it was agreed that 100,000 tonnes of sand per year could be removed from the Ainsdale foreshore by scraping sand from the tops of the ridges between Shore Road and Selworthy Road. In December 1977, permission was granted for the removal of 400,000 tonnes per year from 3.9 square kilometres on the Horse Bank. Sand has continued to be extracted from the Horse Bank since 1977. Southport sand has exceptional qualities for the foundry trade and for polishing glass. At present 20– 30% of the sand extracted is transported to Doncaster where it is used to polish safety glass. Ecosystem management of the Sefton dunes Planners are faced with a number of questions: Whether to restore and preserve the sand-dune complex Whether to preserve the pine woods and preserve one of the two remaining colonies of red squirrel in the United Kingdom Whether to allow nature to take its course but to help the dunes recover Whether to create a mixed community of ecosystems in the area by carefully modifying existing conditions. For example, the removal of a major percentage of tree and scrub cover within the existing frontal woodland area would help re-establish and maintain a spectrum of habitats including bare dunes, dune slacks, scrub and scattered groups of trees suitable for a wide range of associated species. In contrast, a complete clearfell of the pines would allow mobile dunes and associated plants and animals to inhabit the area currently occupied by frontal pine plantations. This would increase the biodiversity of the area, return the soils to a natural condition, and even allow groundwater levels to recover. At Formby, habitats present include mobile and fixed dunes (Figures 7 and 8) and a large area of coniferous pine plantation. The dune front is eroding at rates between 3 and 5 metres per year. Figure 7 – Fixed dune at Formby. Figure 8 – Mobile dune at Formby. Environmental Impact Assessment English Nature are in the process of identifying the best way to manage part of the seaward area at Ainsdale Sand Dunes National Nature Reserve (Figure 9). Here, there is a project to recreate the natural dune landscape destroyed by the pine plantations. It is hoped that the removal of the pine plantations on the frontal dunes will encourage recolonisation by specialised plants such as yellow bartsia, and animals such as the protected sand lizard and natterjack toad. Monitoring of the project shows that this is already a success. Figure 9 – Ainsdale Sand Dunes National Nature Reserve. The Forestry Commission conducted an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) to assess the implications of future management proposals for the seaward part of Ainsdale Sand Dunes National Nature Reserve. The major issues that required consideration during the EIA included: Landscape and visual amenity Physical processes Biodiversity and nature conservation Recreation and tourism. The Consultation Area was 46.5 hectares in extent, and comprised 22.4 hectares of frontal pine woods, 9.8 hectares of mixed scrub and 14.31 hectares of dunes with scattered scrub. The habitats of primary conservation importance were the shifting dunes with marram grass, and the fixed dunes with herbaceous vegetation and humic dune slacks. Species of national and international significance also occur within the Consultation Area, including great crested newt, sand lizard, natterjack toad and red squirrel. The need for the construction of a new forest road for emergency access and management of the frontal area was identified. The four alternative management methods which were put forward as possibilities are listed below. Option A – ‘Do the minimum’ This would involve the least possible intervention while maintaining levels of public safety. Management of the frontal woodlands would be limited to activities such as extinguishing fires, making safe any trees which are destabilised through windthrow or as a result of coastal erosion, and the control of any future scrub invasion of existing open habitats. This option would result in the retention of 22.4 hectares of pine plantation, leaving 14.31 hectares of open dunes with scattered scrub and 9.8 hectares of mixed scrub within the Consultation Area. Option B – ‘Woodland management’ This option would aim to create a varied habitat structure, with a diverse age range of trees and scrub, and a healthy habitat structure. It would lead to similar quantities of habitat present within the Consultation Area as Option A. However, there may be some slight temporary increase in open habitats. This option would improve the quality of the frontal woodlands for associated species, notably the red squirrel. Option C – ‘Incomplete felling’ This option would involve the removal of a major percentage of tree and scrub cover within the existing frontal woodland area. A total initial tree and scrub component of 10–15% of the existing cover would be retained, decreasing to approximately 10% by 2024. The aim of this option would be to re-establish and maintain a spectrum of habitats including bare dunes, dune slacks, scrub and scattered groups of trees. Option D – ‘Complete clearfell’ This option would result in the eventual removal of all the pines within the Consultation Area, with the retention of some willow and alder, but amounting to no more than 5% cover. This is the maximum allowable scrub cover for humic dune slack, dunes with creeping willow, and fixed dune grassland. The aims of this option would be to create mobile dunes and associated floral and faunal communities in the areas presently occupied by frontal pine plantations, and to reduce the rate of natural succession to scrub woodland. The assessment concluded, in 2004, that there would be greater biodiversity and nature conservation gains through the adoption of either Options C or D over Options A or B. This was mainly due to gains of internationally important habitats and species under Options C and D. These benefits were particularly evident in the long term (over 10 years). From the assessments carried out, it was concluded that Options C and D both represent significant biodiversity and nature conservation gains and benefits in terms of physical processes over Options A and B. Options A and B are more compliant with landscape plans and policies in the short term, but Options C and D are more so over a longer timescale. Conclusion The Sefton coastline is a very active one. There are natural processes operating as well as humaninduced changes. Ironically, attempts at recreating a more natural landscape are limited by the popularity of one of the artificial landscapes, namely the pine woods at Formby and their population of red squirrels. It is likely that pressure on this stretch of coastline will increase as a result of changes in the physical environment (sea level rises and increased storm activity), as well as increased visitor pressure on the dunes. Maintaining a variety of ecosystems, as well as allowing for recreational activities, may well prove difficult to balance.