Should I vaccinate my horse against strangles

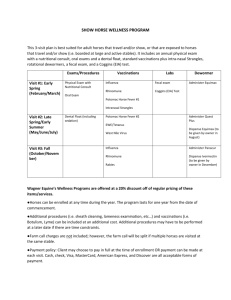

advertisement

Should I vaccinate my horse against strangles? Strangles Vaccination| Because the site of entry of this organism is through contamination of the upper respiratory tract, the most ideal method of stimulating immunity is by eliciting a secretory antibody response (IgA and IgG) in the local respiratory tissues. The intranasal vaccine (Pinnacle I.N.) recently developed by Fort Dodge Laboratories takes advantage of this mechanism of protective immunity. Previously, all vaccination strategies against strangles have relied on intramuscular injections that elicit a systemic immune response. These vaccines have had limited efficacy, only curtailing disease in 60-70 percent of those cases challenged by the organism. In addition, many times the intramuscular injections are accompanied by sore muscles, malaise, and a fever. These secondary vaccine reactions may last for as long as a week. Although these complications occur in a small percentage of horses, many horse owners are concerned by these adverse reactions. Having weighed the risks, many have considered that the intramuscular vaccine is seemingly as bad as the horse contracting the disease. For that reason, use of the strangles vaccine has been limited by horse owners until the advent of the intranasal form. The intranasal strangles vaccine is given as a series of two doses spaced 2-3 weeks apart. The material is a live avirulent S. equi organism that is freeze dried and then reconstituted with a special diluent just prior to administration. The 2 ml dose is squirted through a nasal canula into a nostril to reach the local area of the upper respiratory tract. This provides the best protective response since it stimulates the production of locally produced antibody at the level of an infectious invasion into the system. This prevents attachment of the organism to tonsil receptors, and may prevent tissue invasion of the organism if it does manage to adhere to the receptive respiratory tissues. In the clinical trials associated with this product, there was a reduction in the clinical disease observed in vaccinated horses. However, despite "protection" derived from the intranasal vaccine, 40 percent of horses challenged with the organism did still develop clinical signs of disease as opposed to 60 percent of unvaccinated horses that were challenged with the organism. Morbidity was decreased, and of those that did get sick, the clinical signs were reduced by 65 percent as compared to unvaccinated horses. Just as with the intramuscular vaccines, no horse can receive complete protection from the strangles organism when challenged. However the intranasal vaccine shows promise in reducing the number of horses affected and the severity of the infection if it occurs.