Best Case

advertisement

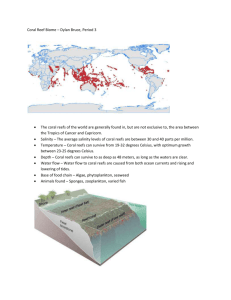

Q&A: THE IMPLICATIONS OF CLIMATE CHANGE FOR AUSTRALIA'S GREAT BARRIER REEF (For a PDF copy of the full report, see www.wwf.org.au. For an easy to navigate version on CD-Rom, contact Richard Leck, rleck@wwf.org,au ) 1) What are the key findings of this report? This report confirms the extreme risk that the world’s most diverse marine ecosystem, coral reefs, face if the earth continues to warm. By using a new index developed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Centre for Marine Studies at the University of Queensland in Australia projections of coral reefs under a warming world were developed. All projections reveal that even under the best circumstances, less than 5% of the coral populations on the Reef today will be left. The key though is how corals fair beyond 2050. Under scenarios in which greenhouse gases continue to build up in the atmosphere, coral populations will be decimated to a point where recovery may have to wait centuries. Under more responsible scenarios in which greenhouse gas emissions are reduced rapidly and global average temperature change stays below 2 degrees Celsius, large scale coral populations will rebuild much quicker. This has to occur with a concerted effort to afford reefs much greater protection. The report also develops four scenarios for the future of the Great Barrier Reef and the industries that depend on them, primarily tourism and fisheries. The news is not good. Under the worst case scenario, coral populations will collapse by 2100 and the reestablishment of coral reefs will be highly unlikely over the following 200-500 years. Under the best case scenario, coral cover will be dramatically reduced by 2100 but will recover over the following century as the climate stabilizes again." Under the best case scenario, which involves deep cuts to greenhouse emissions, solutions remain for people and industry. Under all other scenarios, devastating impacts are inevitable. Tourism and fisheries appear to be the casualties of the worst-case climate change scenarios, as reefs degrade to less appealing and less ecological supportive ecosystems. In the worst case scenario, by 2020 mid-shelf reefs in the Great Barrier Reef will have half the coral they had in 1990 and will be starting to register negative appeal to tourists. By 2040, these reefs will no longer by dominated by corals. Algae and other less attractive organisms will dominate. In the best case scenario, the decline in the abundance of corals is delayed. One of the most critical features of this scenario is that the climate stabilizes within a short period of time, allowing ecosystems like coral reefs to regain their prominence in our oceans. In all scenarios, treating marine ecosystems like coral reefs carefully becomes a central feature. This means that other stressors on coral reefs such as over-fishing and water-borne pollutants must be reduced to allow coral reefs any chance of surviving what is shaping up to a be a century of stress driven by our changing climate. The new zoning plan for the Great Barrier Reef, which establishes a representative network of no-take zones, and the new Reef Water Quality Protection Plan, are two such examples of the types of changes that must occur as we move through this difficult period. While these steps need to be applauded as measures to increase the Reef’s ability to bounce back under stress, the Australian government needs to develop and implement an action plan to achieve rapid cuts in greenhouse gases. The worse case scenario means that climate will continue to change for centuries and the recovery of the earth’s ecosystems may take centuries if not millennia. Under the best case scenario, greenhouse gas emissions are reduced rapidly and the global average temperature stabilizes at no more than 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Under the worse case scenario, greenhouse gases continue to build up in the atmosphere and the global average temperature rises 3 degrees above pre-industrial levels. The temperature will continue to move upwards for many hundreds of years. To ensure the best case scenario, developed countries such as Australia will need to have reduced their emissions by 80% (based on 1990 levels) by 2050. By 2100, emissions will need to be close to zero. 2) What will happen to the Great Barrier Reef at 2 degrees Celsius temperature increase? The report looks at a number of scientific scenarios, which are based on the IPCC family of scenarios. The B1 scenario is based on a global average temperature rise of just under 2 degrees Celsius by 2100. The following table presents projections based on the best case B1 scenario for the Great Barrier Reef: Year after which reefs have half the coral they had in 1990 and are starting register negative appeal to tourists. Year by which reefs are no longer coral dominated. B1 Inshore 2035 2070 Mid-shelf reefs 2030 2060 Offshore reefs 2035 2070 4) How will climate change affect the economy around the Great Barrier Reef? The economic story focuses on the largest and most reef-dependent industry, tourism. Not surprisingly, tourism is vulnerable despite its well-known adaptability, and that this will affect the regions along the Reef. Significantly, all four scenarios start about the same way over the next 20-30 years because past increases in CO2 levels are irreversible in their impact on global warming. However, depending on the extent to which the world starts now to reverse the technologies that cause the worst increases in CO2, trends beyond 20-30 years will be very different, ranging from continued rises in one scenario to significantly lowered levels in others. The economic loss, while considerable whichever scenario story prevails, will be significantly lower in the long term under the ecologically responsible worlds depicted by our scenarios B1 and B2, especially the latter assuming that it merges eventually into global policies reinforced by local community efforts. A1 A1 is driven by strong economic growth and strong international institutions. This economic scenario is associated with the severe A1 family of scientific scenarios. This scenario has the second highest direct losses to tourism and fisheries plus flow-on effects for the regional economies along the GBR coastline. In the global economic growth-driven A1 scenario, where environmental considerations take a back seat at least over the next two decades, the total accumulated estimated loss (from 2001 to 2020) to local Queensland communities along the GBR coastline by 2020 amounts to $AUD5.6 billion. A2 A2 is also driven by strong economic growth but the world is divided into separate geopolitical trading blocks. This is the worst case socio-economic scenario, and is associated with the severe A2 family of scientific scenarios. This economic scenario has the highest direct losses to tourism and fisheries plus flow-on effects for the regional economies along the GBR coastline. The A2 scenario world represents a worst case to be vigorously avoided for the regions along the Reef. Here the total estimated loss to local Queensland communities amounts to $AUD8.0 billion, the highest projected loss of the four scenarios. B1 In the B1 economic scenario, global environmental cooperation takes precedence over economic growth. This scenario is associated with the most environmentally benign family of scientific scenarios – B1 (the only set of IPCC scenarios that stay below 2 degrees warming). This economic scenario has the second lowest direct losses to tourism and fisheries plus flow-on effects for the regional economies along the GBR coastline, of the four scenarios. The total estimated loss under scenario B1 is $AUD4.5 billion up to 2020. B2 The B2 economic scenario depicts a world with strong community drivers rather than global environment cooperation. This scenario is associated with the B2 family of scientific scenarios – that are above 2 degrees Celsius increase but not as severe as A1 and A2. This economic scenario has the lowest direct losses to tourism and fisheries plus flow-on effects for the regional economies along the GBR coastline. The fourth scenario, B2, adds a strong local community input to the general environmental priorities adopted in B1. Up to 2020, it shows the lowest loss of $AUD3.5 billion, Best Case To capitalise on both local and global drivers in order to build a best case scenario for both the GBR and its dependent industries, the B2 scenario is assume to merge into the more globally oriented scenario towards the middle of the century. 6) What are WWF’s key recommendations to address this problem? Global temperature rise must be kept within 2 degrees Celsius of the pre-industrial greenhouse gas concentrations in the long term. We must re-stabilize the climate as soon as is possible. The report shows once more that this is essential if we want to keep the world's largest living organism – the Great Barrier Reef. In order to do this, WWF Australia is urging the Australian government to achieve deep cuts in CO2 emissions, with the long term aim of a CO2 neutral future - and this includes ratifying the Kyoto Protocol. WWF has made clear that one of the most important steps in fighting climate change is to switch electricity production from carbon intensive fuels such as coal to clean energy, such as wind, solar and biomass, and to highest efficiency. The power sector is the biggest CO2 emitter, responsible for 37% greenhouse gas emissions. According to WWF studies, industrialised countries can achieve a CO2 neutral power sector by mid of this century. Developing countries will need longer but should have made a considerable move from coal to clean by mid 21st century. (See WWF’s Power Switch Initiative: www.panda.org/powerswitch) For further information: Imogen Zethoven, WWF-Australia Great Barrier Reef Campaign, izethoven@wwf.org.au Anna Reynolds, WWF-Australia Climate Change Programme, areynolds@wwf.org.au Martin Hiller, WWF Climate Change Programme, mhiller@wwfint.org