Volume 29, Number 5 (Eight issues) - digital

advertisement

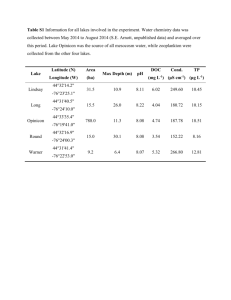

INFLUENCE OF MATERNAL REPRODUCTIVE CHARACTERISTICS ON THE BODY TRAITS OF PRESCHOOL CHILDREN FRANCISCO BRAZA AND CRISTINA SAN JOSÉ Estaciôn BiolOgica de Do/lana, CSIC, Spain The authors studied the influence of maternal reproductive characteristics on their pit-school children’s body traits in a village in southern Spain, assuming that children’s size at prc-schooi age is associated with their future reproductive palterns. The variables considered were: I) mother’s age al menarche, as a more genetically informative variable, 2) as a mote environmental variable, they propose a new index of maternal time availability, and 3) birth weight to control its influence on early patterns of growth. The children’s body trails considered were weight and height, and a body mass index was also computed. According to these results, the mother’s age at menarche is related to those body parameters which probably influence the children’s future reproductive strategies. Human reproductive charactensucs may vary from individual to individual, are short-term (maxiF- within the continuum between reproductive patterns which rancisco Braza and Cristina San José, Estacian BiolOgica de Dodana, CSIC. Spain. This research was supponed by the Spanish DOICYT (project No. PB94-00l0) and by the Ministry of Education and Research (research contract). Thc authors thank [he tcachers from the kindergarten of “Zahara de La Sierra” and the childrcn’s families for their collaboration. Dala were collected with the help of José A. Luna, Chari Carreras, 3. Manuel Mufloz, and Xenia Casanova, which was very much appreciated. The authors are grateful to Enrique Collado, Dr. Pedro Jordano, and Dr. Jiavier Cuervo for their help in analyzing data as well as for [heir comments. ALicia Prieto contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. Prot José RamOn Lorenzo (Fact. CC de La Educacidn, Univ. CIdiz) provided the growth curves and sables on the Andalusian children. Appreciation is due to reviewers including: Prof. Jose Ramon Sanchez, Facullad de Psicologia, Universidad de San Sebastian, Spain, and Prof. Rosario Carreras, Faeultad Dc Formacion del Profesorado, Universidad de Cadiz, Spain. Kcywords: Age at menarche, Mother’s availability, Reproductive strategies, Body traits, Preschool children, Spain. Please address correspondence and reprint requests to: Francisco Braza. Estacidn BioLdgica de Doflana, CSIC, Avda. M’ bsisa s/n, Pabellón del Peru, 41013 ScvilLa, Spain. Phone: +34 5 4232340; Fax: +34 5 4621125; Email: <braza@ebd.csic.es> 417 418 INFLUENCE OF MATERNAL REPRODUCTIVE CHARACTERISTICS mizing mating effort: early menarche, early sexual activity, early first reproduction, high number and low quality of offspring) and long-tenn (maximizing parenting effort: late onset of puberty, late first sexual intercourse and reproduction, and fewer but better quality offspring). AlL these factors could be affected by two kinds of determinants. Firstly, the genetic influence measured by the inheritance of these factors, which would explain the characteristics shared by the individuals and their parents. There are reports suggesting the inheritance of reproductive characteristics as, for instance, the concordance of mothers and daughters in menarche timing (Campbell & Udry, 1995; Graber, Brooks-Gunn, & Warren, 1995; Wolanski, 1995). Secondly, environmental conditions (e.g., nutrition, life quality of life, family context, etc.) could also affect the reproductive characteristics of individuals; and so Chisholm (1993) revised the consequences of early stress on the way people allocate their reproductive effort. Genetic studies suggest that the contribution of genotypic effects to the variance in menarcheal timing is stronger than that of environmental ones (Kaprio, et al., 1995). However, the environmental influence on age of menarche in girls has been extensiveLy evidenced (Belsky, Steinberg & Draper, 1991; Draper & Harpending, 1982; Ellis, Mc Fadyen-Ketchum, Dodge, Petit & Bates, 1999; Graberet al., 1995; Moffit, Caspi, Belsky & Silva 1992; Steinberg, 1988; Wierson, Long & Forehand, 1993). On the other hand, although birth weight is correlated to growth status during childhood, Gofin, Adler, and MaddeLa (1993) pointed out that the influence of birth weight on the early pattern of growth is not maintained through adolescence, and found that, at the age of 14, most of the explained variance was attributed to the measurements at the age of six. Khan, Schroeder, Martorell, Haas, and Rivera (1996) demonstrated (hat a linear growth retardation during this period of early childhood is associated with a delay in menarche. Draper and Harpending (1982) have shown that there is a sensitive period in early childhood, approximately from birth to five years oLd, and that physical and behavioral changes during this period may have significant repercussions on the onset of puberty and future reproductive strategies of individuals. Thus, assuming that the children’s physical development at preschool age is important with respect to their future reproductive patterns, the aim of the present research is to study the reLationship between maternal reproductive patterns (age at menarche, number of siblings, interbirth interval) and the variation of the body traits of pre-school girls and boys. — INFLUENCE OF MATERNAL REPRODUCTIVE CHARACTERISTICS 419 METHOD PARTICIPANTS The study was carried out in Zahara de la Sierra, a village of around 2000 inhabitants in the mountain ranges of Cádiz (southern Spain) during 1997. The participants were a group of pre-school children (n= 38; 25 girls, 13 boys), who belonged to Lower-middle socio-economic class families. Both the living conditions and nutrition patterns in a restricted area are homogeneous. In aLl cases both mother and father were living with the children. A demographic profile of the sample is shown in Table 1. DEMOGRAPHIC TABLE 1 CHARACTERISTICS OF ThE SAMPLE (N= Girls (n=25) Al Age of the ehildren (years) Mother’s age at the chiJd’s birth (years) Father’s age at the child’s birth (years) Mother’s age at menarche (years) Birth weight (kg) of the child studied 5.823 27.240 30.680 12.400 3.218 38) Boys (n=13) SD 0.447 5.659 6.619 1.155 0.466 Al 5.577 28.462 30.615 12.692 3.405 SD 0.435 4.594 6.158 1.251 0.440 VAR1ABLES MEAsURED A) Dependent variables. 1) Height: distance between the interparietal union and the floor (in meters). 2) Body weight (in kilograms). 3) A body mass index (hereafter BMI = body weight/height squared) was also computed. The heights and weights of pre-school children were obtained during the first days of the school year. A trained staff member collected both measurements using standard anthropologic procedures, The children’s heights and weights were measured using a standard tape measure mounted to a wall, and electronic bathroom scales. Although the range of ages of the children is small, there is still an age-related growth effect in height and weight. Height and the weight values were substituted for their z-scores ((Weight (or Height) ii)/a) with respect to the distribution of the same sex and age of Andalusian children (Fact. CC de Ia Educación, Univ. de Cádiz). - B) independent variables. The mothers were questioned about their reproductive histories (age at menarche, number, age and sex of their previous children, and birth weight of the children studied). The variabLes selected were: 420 INFLUENCE OF MATERNAL REPRODUCTIVE CHARACTERISTICS 1) Mother’s age at menarche (hereafter MAM). 2) Maternal Time Index (hereafter MTI): In order to assess the mother’s time available for the chiLd studied, the authors propose a new index which takes into account the number of siblings and birth interval up to the moment the studied child is measured; this index could provide infonnation about the proximal family environment where children grow up. The index was calculated as follows: MTI=Z 1=0 Sp+SFj j=o = Birth following the birth of the study subject; Ti = Interval between one birth and the next or up to the moment when the study subject was measured (T0 is the interval between the birth of the study subject and the next birth) S= number of siblings precedent to the birth of the subject studied; SFJ= number of siblings born in birth j, being j=O the birth in which the subject studied was born. 3) Birth weight (hereafter BW) of the studied child: in order to control its possible influence on the early pattern of growth. ANALYSIS Girls and boys were analyzed separately, taking into account that sexual differences in human parental investment and sexual selection are to be expected (Kenrick & Trost, 1993). A significant difference in weight at preschool age was detected, the girls being heavier than the boys (ANOVA F = 5.773, p = 0.0216), MultipLe least square regressions were used (Abacus Concepts, Statview 4.1, 1992) to analyze the relative contribution of maternal reproductive parameters to the children’s body characteristics at preschool age. RESULTS No significant correlation was detected between the three maternal reproductive characteristics (MAM, MTI, and BW) considered in the case of the preschool girls (Pearson’s Correlation ranging -0.267 r S 0.127). Table 2 shows that, when regressing the body traits of pre-school girls to MAM and to MTI, a significant negative contribution of the MAM to both weight and BMI at pre-schooL age was found. The MTE did not contribute significantly to the body traits of girls at pre-school age. INFLUENCE OF MATERNAL REPRODUCTIVE CHARACTERISTICS 421 TABLE 2 BODY TRAiTS OF PRESCHOOL OWLS REGRESSIONS ON MuIHER’s AGE AT MENARCHE (MAM) AND MATERNAL TIME INDEX (MTI) p Coefficient Lntercept MAM MTI = 0.217, df= 22. F = 3.050, p 20.858 -0.452 a) Weight -0.068 = -2.378 -0.360 0.0223 0.0265 0.7223 -0.289 0,616 -1.326 0.7754 0.5443 0.1986 2.459 0.0677 Coefficient Intercept b) Height MAM MTI W= 0.082, df= 22, F = 0.981, p = 0.3909 -2.248 0.127 -0.273 p p Coefficient Intercept MAM MTI 0.332, df = 22, F 5A66, p 14.961 -0.581 0.068 C) BMI = 3.200 -3.306 0.389 0.0041 0.0032 0.7009 0.0118 As can be seen in Table 3, when regressing the body traits of pre-school girls to MAM and to 8W, there was a tendency towards a negative contribution of the MAM to weight at pre-schooL age, and a significant negative contribution of the MAM to the BMI was found. The 8W did not contribute significantly to the body traits of girls at pre-school age. TABLE 3 BODY TRAITS OF PRESCHOOL GiRLS RLGRESSIONS ON MOTHER’S AGE AT MENARCHE (MAM) AND BIRTH WEIGHT (BW) OF THE CHILD STUDIED p Coefficient Intercept a) Weight MAM BW R2=0.291, df= 22, F = ‘4.SI9,p 8.734 -0.383 0.291 = 0.795 -2.058 1.563 Intercept MAM BW R20.I44,df=22F= l.847,p=O.1813 b) Height -16.537 0.194 0.382 p -1.616 0.948 1.864 0.1204 0.3535 00757 2.248 -3.106 0.188 0.0349 0.0052 ** 0.8523 p Coefficient 14.354 -0.563 0.034 = * 0.0227 Coefficient Intercept c) BMI MAM BW R2= 0.328, df= 22, F S.38O,p 0.4354 0.0516 0.1324 0.0125 When considering the correlation between the three maternal reproductive characteristics in the case of boys, a significant positive reLationship was detected between MAM and MTI (r = 0.647, p = 0.0149, Pearson’s Correlation) only. 422 INFLUENCE OF MATERNAL REPRODUCTIVE CI-IARACTERISTICS Table 4 shows that, when regressing the body traits of preschool boys to MAM and ?VITJ, a significant negative contribution of MAM to the weight at pre-school age was found. As can be seen in Table 5, when regressing the body traits of boys to MAM and to 8W, a significant negative contribution of the MAM to the weight and height at pm-school age was found. A significant contribution of the 8W to the height of boys at pre-school age was also found. TABLE 4 BODY TRAITS OF PRESCHOOL Boys REGREsSIONS ON MOTHER’S AG! AT MENARCHE MATERNAL TIME INDEX (M’I’I) Coefficient Intercept MAM Ml’! R2= 0.419. df= 10 F = 3.609, p 22.021 -0.729 0.139 a) Weight = 0.0661 tntercept b) Height = 0.275, df MAM = MTI 10, F = 1.893, p = 0.2008 Intercept MAM c)BMI MTI R2= 0.239, df= 10, F = I 2.509 -2.306 0.441 (NIAM) AND p 0.0310 0.0438 * 0.6685 Coefficieni a’ p 27.586 -0.604 1.843 -1.710 0.140 0.398 0.0951 0.1181 0.6992 Coefficient r p 7.721 -0A95 0.009 1.545 -L.369 0.1534 0.2011 0.9804 0.025 L573, p = 0.2548 TABLE S BODY TRAITS OF PRESCHOOL Boys REGRESSIONS ON MOTHER’S AGE AT MENARCHE BIRTH WEIGHT (BW) OF THE CHILD STUDIED Coefficieni Intercept 10.336 MAM BW R2= 0.588. df= 10, F = 7.l23,p = 0.0119 -0.647 0.424 a) Weight b) Height = 0.590, df = 2.087 Coefficient a’ tnrercept 4.535 MAM -0.524 0.375 -2.589 2.824 13W 10, F = 7. t97, p = 0.01 t6 Intercept c) BMI I 1.301 -3.185 MAM BW R1=0.265,df= tO,F= I.8O6,p=0.2t40 0.572 (MAM) AND p 0.2224 0.0097 0.0635 p 0.7152 0.0270 * 0.0180 * Coefficient r p 5.805 -0.492 1101 -1.816 0.2969 0.0994 0.162 0.597 0.5640 When regressing the body traits of preschool children (boys and girls) to MTI and to 8W, no significant conthbution was detected. INFLUENCE OF MATERNAL REPRODUCTIVE CHARACTERISTICS 423 DISCUSSION A significant negative contribution of MAM to weight of girls and boys at preschool age has been detected independently of either MTI or BW. Furthermore, and also when controlling for MTI or BW, these results reveal a higher BMI in the we-school girls of earlier-maturing mothers, which can be considered as a good estimate of body fatness (i.e., the proportion of body mass fat, Deurenberg, Weststrate, & Seidell, 1991). A relationship between a woman’s amount of body fat and the onset of menarche has previously been demonstrated (Ellison, 1982; Frisch, 1988; Frisch & McArthur, 1974), young girls not entering puberty until they have reached a critical ratio of body fat to muscle. Thus, at least for girls, a greater influence of BMI at pre-school age on the future onset of menarche is to be expected. Furthermore in these results, it is interesting to note that, when controlling for BW, the MAM has a negative significant contribution in height at pre-school age but only in boys. The pubertal onset for boys has traditionally been associated with behavioral factors and probably a bigger size (weight and height can be considered as estimates of body size) at pit-school age contributes to an early reproductive behavior, (Capaldi, Crosby, & Stoolmiller, 1996). Considering that children of earlier-maturing mothers probably also mature earlier, it can be expected that these children of the same age are physically further developed than children of later-maturing mothers. Moffit, et al. (1992) have previously suggested that children of earlier-maturing mothers also matured earlier; results from Wolanski’s study (1995) of Mexican schoolgirls also suggested this possibility by reveaLing a correlation between the age at menarche of mothers and daughters; and Gofin, et al. (1993) pointed out that early menstruating girls were taller and heavier than non-menstruating girls already at six years old. According to the results of this study, MAM is strongly related to those body parameters that probably influence the children’s future reproductive strategies. That is, in girls, the mother’s age at menarche is more closely related not only to body weight but also to the store of fatness, whereas it is more related to body size in boys. Following the prediction of life-history theories, in a short-term reproductive strategy low-quality offspring are more to be expected. The relationship between early menarche of mothers and more physically developed children at preschool age does not mean that these children will attain a better physical condition as adults. In the authors’ opinion, advanced development at preschool age anticipates the onset of puberty, which probably stops their growth. It has long been recognized that maturation is accompanied by a decrease in or cessation of— growth in many organisms, and recent research corroborates the results of several previ - — 424 INFLUENCE OF MATERNAL REPRODUCTNE CHARACTERISTICS ous studies that describe shorter statures and higher body mass indexes during adulthood in early-maturing females (Kirchengast, Gruber, Sator, & Huber, 1998). As regards family context, in Chisholm (1993), Pavlik pointed out that the period from five to seven years old is important for the development of the child’s neuroendocrine phenotype, and early stress may be associated with high-mating effort reproductive patLerfls. Belsky, et al. (1991) have proposed that the first five to seven years of experience in the family enables a child to assess the availability of resources and the durability of parental bonds as a basis to develop his or her reproductive strategy. Ellis et al, (1999), suggest that the quality of fathers’ investment in the famiLy is the most important feature of the proximal family environment relative to daughters’ pubertal timing. In spite of the importance of family experience in early childhood on future reproductive strategies, the authors have not detected a significant contribution of the context where children develop (MTI, i.e., time of maternal availability, birth interval, arid family size) to the children’s body traits at pre-school age when controlling for both MAM or BW. Other authors (Kim, Smith, & Palermity, 1997; Kim & Smith, 1998), although they found developmental links between childhood stressors, onset of puberty, arid postpubertal reproductive behavior, consider that early puberty and postpubertal sexual behavior might be more influenced by intergenerational transmission of genetic characteristics. Since birth weight might be considered as an outcome of maternal phenotype (maternal effects) rather than of genetic constitution of the offspring, it might be thought that the positive contribution of boys’ birth weight detected to height at pre-school age when controlling for MAM, might suggest a maternal environment’s influence during the prenatal period, at least for boys, in the determination of their future reproductive strategy. Furthermore, in boys a positive correlation between MAM and MIT was found, that is —later maturing mothers of boys present long birth intervals and few offspring, suggesting a higher investment in boys than early maturing mothers. Considering that the allocation of resources before birth (BW) is related to the onset of boys’ puberty, this result could be supporting also, at least in boys, the possibility of a maternal environmental influence in Lhe reproductive strategy of their children. Thus, in boys, besides the genetic influence detected (early or later maturing mothers having early or later maturing children respectively), an environmental influence has also been found. Body traits irrespective of age are genetically and environmentally affected and the contribution of each factor at each age is difficult to assess. Future research might explore, for girls as well as for boys, models considering simultaneously variables informative of the environment as well as those more genetically informative, L INFLUENCE OF MATERNAL REPRODUCTIVE CHARACTERISTICS 425 REFERENCES Abacus Concepts, StatView (Version 41). (1992). Berkeley, CA: Abacus Concepts, Inc. Belsky, 3., Steinberg, L. & Draper, F. (1991). Childhood experience, interpersonal development, and reproductive strategy: An evolutionary theory of socialization. Child Development, 62, 647-670. Campbell, B. C, & Udry, J. R. (1995). Stress and age at menarche of mothers and daughters. Journal of Biosocial Science, 27, 127-134. Capaldi, D. M., Crosby, L. & Stoolmiller, M. (1996). Predicting the timing of first sexual intercourse for at-risk adolescent males. Child Development, 67, 344-359. Chisholm, J. 5. (1993). Death, hope and sex: Life-history and the development of reproductive strategies. Current Anthropology, 34, 1-46. Draper, P. & Harpending. H. (1982). Father absence and reproductive strategy: An evolutionary perspective. Journal of Anthropological Research, 35. 255-273. Deurenberg, P., Weststrate, J. A. & Seidell, J. C, (1991). Body mass index as a measure of body fatness: Age- and sex-specilic formulas. British Journal of Nutrition, 65, 105-114. Ellis, B. J., McFadyen-Ketchum, S., Dodge, K. A., Petit, G. S. & Bates, J. E. (1999). Quality of early family relationships and individual differences in the timing of pubertal maturation in girls: A Longitudinal test of an evolutionary model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 387-401. Ellison, P. T. (1982). Skeletal growth, fatness, and menarcheal age: A comparison of two hypotheses. Human Biology, 54, 269-281. Frisch, R. E. & McArthur, J. (1974). Menstrual cycles: Fatness as a detenninant of minimum weight for height necessary for their maintenance or onset. Science, 185, 949-951. Frisch, R. E. (1988). Fatness and fertility. Science in America, March, 88-95. Gofin, R., Adler, B. & Maddela, R. (1993) Birth weight and weight, stature, and body mass index at ages 6 and 14 years. American Journal of Human Biology. 5, 559-564. Graber. J. A.. Brooks-Gunn, 3. & Warren, M. P. (1995). The antecedents of menarcheal age: Fleredity, family envionrtnent, and stressful life events. Child Development, 66. 346-359. Kaprio, J., Rimpela, A., Winter. T., Viken, R. J., Rimpela. M. & Rose, R. J. (1995). Common genetic influence on BMI and age at mensrche, Human Biology, 67, 729-753. Khaji, A. D., Schroeder, D. G.. Martorell, R,, Haas, J. D. & Rivera, J. (1996). Early childhood detenninants of age at menarche in rural Guatemala. American Journal of Human Biology, 8, 717-723. Kenrick, D. T. & Trost, M. R. (1993). The evolutionary perspective. In Beau & Stenberg (Eds.), The psychology of gender (pp. 148-172). New York: Guilford Press. Kim, K. & Smith, P. K. (1998). Childhood stress, behavioral symptoms and mother-daughter pubertal development. Journal of Adolescence, 21, 231-240. Kim, K., Smith, P. K. & Palermisy, A. (1997). Conflict in childhood and reproductive development. Evolution and Human Behavior, IS, 109-142. Kirchengast, S., Gruber, D., Sator, M. & Huber, 3. (1998). Impact of the age at menarche on adult body composition in healthy pre- and post-menopausal women. American Journal of Pltysiological Anthropology, 105, 9-20. Moffit, T. B., Caspi, A., Belsky, J. & Silva, P. A. (1992). Childhood experience and the onset of menarche: A test of a sociobiological model, Child Development, 63, 47-58. Steinberg. L. (1988). Reciprocal relation between parent-child distance and pubertal maturation. Developmental Psychology. 24. 122-128. Wierson, M., Long, P. J. & Forehand, R. L. (1993). Toward a new understanding of early menarche: The role of environmental stress in pubertal timing. Adolescence, 28, 913-924. Wolanski, N. (1995). Non-genetic family factors and development of schoolgirls from Progreso in Mexico. Mankind Quaterly. 36, 159-177. CALL FOR PAPERS Articlcs on all aspects of Social Psychology. Personality and Developmental Psychology are welcome for consideration, and will receive professional and prompt attent ion. Social Behavior and Personality is proud of the fairness of its review process. and is noted for its consideration towards all prospectivc authors. Receipt of papers will be acknowledged immediately by email and confirned via airmail. Review of your manuscript will normally be completcd within S wecks of receipt. If accepted and scheduled For publication, your manuscript will he puhlished promptly, normally within 6 months. Proofs of the article will be airmailed to authors and any amendmeuts should be returned or advised promptly (preferably via email or fax: otherwise by airmail). Staff and students at Institutions which subscribe to the journal will have free online access 10 your article, as well as lhe hard copy suhseription.The journal is fully covered by the world’s abstracting, indexing and retrievaL networks. We are willing to entertain suggestions as to reviewers for your manuscript, in addition to those whom we would normally consider. Feel free to suggest the names of two reviewers, and please include email and postal addresses if possible. Suitably quaiil’ied persons are always welcome to register an inleresi in being appointed as peer reviewers for the journal. Please send a brief curriculum vitae and an indication of areas of interest. Detailed information for manuscripts is as follows: Manuscripts tfour copies. double spaced) should he sent via email attachment or airmail. (tf sent via airmail, please send four copies.) Robert A.C. Stewart, PhD, Editor, Social Behaviar and PersonaliLy, Society for Personality Research, P.O. Bos 1539, Palmerston North 5331. New Zealand, Phone: Int’l ISD +64÷6÷355-5736. Fax: Int’l ISD +64+6+355-5424. Email: <stewart@sbponrnal.co in World Wide Web: <http:/iwww.sbp.journal.coin> Please use lest format for this journal ..coc (al Behavior and Prrsonaliiy follows the recommendations of the latest revision of the Publication Manual of the American Psyt hological Association, which is available through the A.P.A., 750 First Street NE, Washington. DC 20002-4242 USA. or weh.www.apa.org, and maybe found in most libraries. Please provide a running head abbreviating the title, which will appear at the top of pages in the published articles. Include also fax, phone numbers, and email address itt the return mailtng address providest. The manuscript should include an abstract, preferably no longer thau 120 words, conforming to she style of Psschological Abstracts, in which it will appear as soon as possible if the article is published. Authors are encouraged to he as succinct as possihle. aLid should retain copies of their own articles, The non-prolit Society for Personality Research shares pait of the cost of puhllcation of an author’s own paper in SPB, with the author(s) concerned. Puhlieatiou costs are based ott length of paper, aud include detailed suhediting. typesetting, initial proofing. ainnailing proofs to authors, printing. collasittg, and binding etc.. Contact Edtsor for advice on current author chare costs. To reduce author share costs it is helpful io look at the length of the article, and to provide a iiopps disk version of the matluscrips. together with the hard copy version. (A t]nppy disk is not necessary if thc mauuscript is seut via email atsachement.) Please identify the word proeessiug progratst used — e.g. Microsoft Word, Word Petfeet. etc., Immediately upon publication, a complimentary copy of the jonmal issue will he aimsailed to each listed author. Also a total of 20 complimentary reprints wilt be sent to the corresponding author. Arrangemetits may he made with the Editor to supply additional reprints or journal issue copies. on a cost basis if required. Social Behavior and Personality AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL Volume 29 2001 Number 5 CONTENTS Francisco Braza and Cristina San José, Estación Biólogica de Donana, CiSC, Spain Influence of maternal reproductive characteristics on the body traits of preschool children 417 Nicolas Michinov, Université Blaise Pascal, France When downward comparison produces negative affect: The sense of control as a moderator Mousa Alnabhan, Mutah University, Jordan, and Michael Harwell, 427 University of Minnesota. USA Psychometric challenges in developing a college admission test for Jordan 445 Giovanni B. Moneta and Fanny Ho Yan Wong, The Chinese University of Hong Kong Construct validity of the Chinese adaptation of four thematic scales of the personality research form 459 Ami Rokach, The institute for the Study and Treatment of Psycho-social Stress, Toronto, Canada,,Miguel C. Moya, Universidad De Granada, Spain, Tricia Orzeck, The institute for the Study and Treatment of Psychosocial Stress, Toronto, Canada, and Francisca Exposito, Universidad De Granada, Spain Loneliness in North America and Spain 477 M. Posse, Huddinge University Hospital, Sweden, C-E. Häkanson, Occupational Health Service, Sweden, and T. Hâllstrom, Huddinge University Hospital, Sweden Alexithymia and psychiatric symptoms in a population of nursery workers: A study using the 20 item Toronto alexithymia scale 491 Huda Ayyash-Abdo, Lebanese American University, NY, USA. Individualism and collectivism: The case of Lebanon 503 — C C a