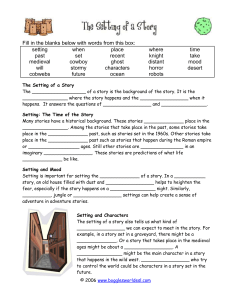

Chapter One: Accessing the Middle Ages

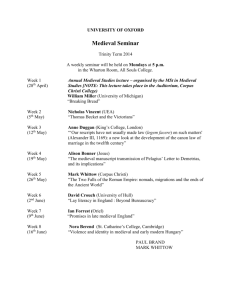

advertisement