Mental Disabilities in the Workplace

advertisement

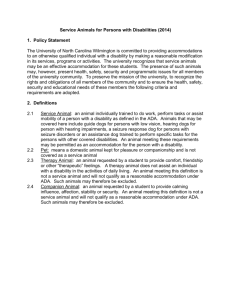

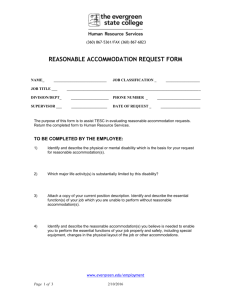

Mental Disabilities in the Workplace Employers face a host of thorny problems ranging from limits on independent psychiatric evaluations to requests for accommodations of "stress." By Stephen P. Sonnenberg So, too, is the amount of employment litigation related to mental disabilities. Employees previously reluctant or unable to litigate mental disability discrimination claims are doing so with increasing frequency. As a result, employers face a host of thorny problems ranging from limits on independent psychiatric evaluations to requests for accommodation of "stress" and other vague, uncorroborated, or hidden emotional problems. Familiarity with the ADA and its interpretation by courts and the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is essential if an employer is to avoid litigation. Congress expressly excluded the following conditions, among others, from the ADA’s definition of "disability": kleptomania, pyromania, exhibitionism, voyeurism, other sexual behavior disorders, and psychoactive substance use disorders resulting from current illegal drug use. Nor are common personality traits protected. Covered mental impairments do not include, for example, poor judgment, a quick temper, or irritability, so long as the traits are not a symptom of a protected mental impairment. Excluded conditions aside, neither the EEOC nor the ADA itself provides a comprehensive list of all potentially protected mental impairments. Rather, EEOC regulations broadly define a mental impairment as "ny mental or psychological disorder, such as mental retardation, organic brain syndrome, emotional or mental illness, and specific learning disabilities." This broad and non-exclusive definition has two implications. First, its open-ended nature, coupled with the subjective and ill-defined nature of emotional illness, virtually ensures that mental health professionals will play a key role in determining -- and disputing -- that an employee suffers from a protected mental impairment. Second, because there is no definitive list of covered mental impairments, employers must analyze disability claims and accommodation requests on a case-by-case basis. The statutory criteria for all impairments, mental or physical, should guide the analysis. As a general rule, the ADA places mental impairments on an equal footing with physical impairments. The ADA prohibits employers from discriminating against a "qualified individual with a disability" because of the disability, in regard to the terms, conditions, and privileges of employment. A person with a mental or physical impairment is a "qualified individual" if he or she is able to perform the essential functions of the job with or without reasonable accommodation. Even if an individual is a "qualified individual," a mental impairment is not automatically a disability. Under the ADA, a mental or physical impairment must "substantially limit" one or more major life activities of an individual. If a qualified employee has a mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activity, has a record of such an impairment, or is regarded as having such an impairment, the employee will likely be entitled to protection under the ADA. Protected status, however, does not entitle an employee to each and every accommodation requested. An employer is not required to accommodate an employee’s mental or physical impairment if doing so would result in an undue hardship. Litigation of mental disability claims often focuses on whether the employee’s claim meets the statutory criteria: is the employee a "qualified individual"?; is the employee substantially limited in a major life activity?; is the requested accommodation a reasonable accommodation?; and/or would the accommodation cause the employer an undue hardship? Tips for Employers 1. If an employee appears or claims to have a mental impairment, scrupulously avoid relying on generalizations or stereotypes regarding mental illness. Analyze situations on a case-by-case basis. The EEOC cautions that the ADA was enacted, in part, to combat the myths and stereotypes upon which employment discrimination against mentally disabled individuals is based. Stereotypes and uncorroborated information about mental impairments should never be the basis for an employment decision. Reject generalizations about mental impairments and, when appropriate, conduct a fact-specific case-by-case analysis. 2. Resist the temptation to play armchair psychologist. A compassionate response to an employee’s workplace problem is always appropriate; playing armchair psychologist is not. An employee with attendance infractions or conduct problems will find it easier to claim disability discrimination if a supervisor asks whether the employee’s difficulties are symptomatic of "too much stress" or a "nervous breakdown." Instruct managers to document an employee’s performance problem or misconduct by specifically describing the deficiency or behavior at issue. 3. If an employee complains that working with his supervisor is too stressful and causes emotional problems, elicit a written admission that he will be able to perform essential job duties only if he has a different supervisor or works in a different location. No matter how debilitating the effects of a mental impairment, it will not be protected under the ADA if it stems solely from an inability to work with a particular supervisor or in a single particular job. Courts and the EEOC agree that an employee is not substantially limited in the major life activity of working unless the employee is significantly restricted in the ability to perform either a class of jobs or a broad range of jobs in various classes. Accordingly, ask (but not mandate) that the employee submit an accommodation request in writing. 4. Consider even vague requests for accommodation from employees, their family members, or their representatives as triggering a duty to engage in an interactive process with the employee. Requests for accommodation of emotional problems are often as vague and ill defined as the underlying impairment. A family member may inform a supervisor that the employee is "falling apart" and needs professional help and "time off"; an employee may blurt out in the midst of a rush project that he is so "depressed and stressed out" that he can "no longer cope emotionally unless something changes." Such comments are more than mere complaints; they are, in part, requests. In response to the "requests" described above, the employer should speak with the employee to clarify his needs and create a written record of the meeting. Assuming that the employee articulates specific requests, the employer need not provide each of the requested accommodations. Rather, it may choose among reasonable accommodations so long as the chosen one is effective. 5. When considering requests for accommodation, remember that the ADA requires employers to accommodate only disabilities that cause substantial limitations, not all disabilities. In other words, a psychiatric diagnosis is not determinative. In response to an employee’s request for accommodation, an employer’s fact-specific analysis should focus not just on the employee’s psychiatric diagnosis but also on the extent to which the employee is limited, if at all, in a major life activity. The analysis should be grounded on the employee’s limitation at the time of the requested accommodation. 6. In misconduct situations, distinguish between prospective and retrospective requests for accommodation and ensure that disciplinary rules are uniformly applied. Courts and the EEOC agree that reasonable accommodation is always prospective, not retrospective. A prospective request for an accommodation that will assist an employee in complying with the company’s conduct rules should generally be granted, so long as it does not cause the employer an undue hardship. However, if an employee is unable to perform essential functions of her job even with reasonable accommodation, she is not a qualified individual under the ADA. 7. Don’t be intimidated by psychiatric jargon; mentally impaired employees can often be accommodated in the same ways as physically impaired employees. Most individuals are more familiar with physical than mental disorders. The same types of accommodations (e.g., sick leave, time off, reduced hours) that are afforded to employees with physical impairments should be considered for employees with mental impairments. 8. Designate one person or office to review all company requests for additional medical information about employees; ensure that such requests are narrowly tailored. Requests for accommodation based on claims of "stress " or "difficulty coping " are often suspect because the mental impairments on which they are based are hidden, unlike some physical impairments. In response to such vague complaints or equally vague diagnoses from mental health professionals, employers may request certain additional medical information. Imposing limits on the type and scope of the information requested is the key to avoiding liability. As a general rule, when the medical impairment or need for accommodation is not obvious, an employer may ask an employee for reasonable documentation about his or her purported disability and functional limitations. Reasonable documentation does not mean an employee’s entire medical record; it is limited to documents necessary to establish that the employee has an ADA disability and that the disability necessitates a reasonable accommodation. 9. Require that employees submit to an independent psychiatric examination only in limited circumstances; designate one person or office to review and issue such requests. To guard against abuse and malingering, an employer may require that a psychiatrist or psychologist of its choice evaluate an employee if one of three conditions is met. First, a psychiatric examination may be required if an employer has a reasonable belief based on objective evidence that an employee’s ability to perform essential job functions will be impaired by a medical/psychiatric condition. Second, if an employee requests a reasonable accommodation, and either the mental impairment or need for accommodation is not obvious, an employer may request an independent psychiatric exam. Third, an employer may require a psychiatric examination if, based on objective, scientific information, the employee poses a direct threat to the health or safety of himself or others because of a medical condition. 10. Treat all information about an employee’s psychiatric impairment as confidential, whether disclosed by the employee, a mental health professional, or a coworker. The ADA requires that employers keep confidential all information regarding their employees’ medical conditions, including information about their psychiatric disabilities. Even medical information voluntarily disclosed by an employee should be treated as highly confidential. 11. Review and revise job descriptions to include references to employees’ ability to cope with stressful circumstances and to cordially interact with coworkers to accomplish common tasks. Numerous courts have held that mental stability and the ability to get along with coworkers are essential functions of a job, without which an employee is not qualified. Courts have also held that the inability to cope with a stressful work environment does not constitute a protected disability. 12. Develop relationships with mental health professionals and accommodation experts and maintain a database regarding their work. Accommodation requests for mental impairments are typically supported by psychiatrists and psychologists. Employers can employ such professionals to their advantage. In situations involving a direct threat, for example, the immediate referral of an employee to a psychiatrist with expertise in violence assessment is often imperative. Source: Sonnenberg, S. P. (June 2000), "Mental Disabilities in the Workplace," Workforce, , Vol. 79, No. 6, pp. 142-146. http://www.workforce.com