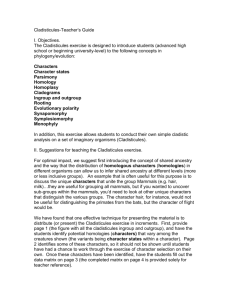

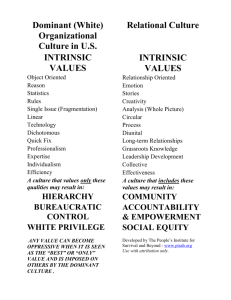

A cultural perspective on intrinsic motivation

advertisement