1.2 environmental information and sustainable - GRID

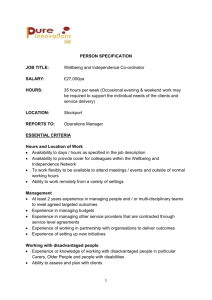

advertisement