Chapter 21: Adulthood: Cognitive Development Chapter Preview

advertisement

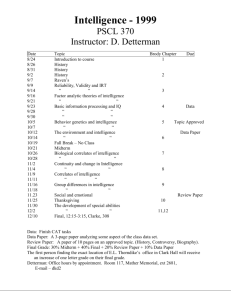

Chapter 21: Adulthood: Cognitive Development Chapter Preview The way psychologists conceptualize intelligence has changed considerably in recent years. Chapter 21 begins by examining the multidirectional nature of intelligence, noting that some abilities (such as short-term memory) decline with age, while others (such as vocabulary) increase with age. This section includes a discussion of the debate over whether cognitive abilities inevitably decline during adulthood, or may possibly remain stable or even increase. The chapter then examines the contemporary view of intelligence, which emphasizes its multidimensional nature. Most experts now believe that there are several distinct intelligences rather than a single general entity. The next section of the chapter discusses the cognitive expertise that often comes with experience, pointing out the ways in which expert thinking differs from that of the novice. Expert thinking is more specialized, flexible, and intuitive, and is guided by more and better problem-solving strategies. The chapter concludes with a brief discussion of the recent shift in society in which family skills have become more highly valued when performed by both women and men. What Have You Learned? The “What Have You Learned?” questions at the end of the text chapter are reprinted here for your convenience in checking students' understanding of the chapter contents. 1. How successful are geneticists at finding g? 2. What does cross-sectional research on IQ scores throughout adulthood usually find? 3. What does longitudinal research on IQ scores throughout adulthood usually find? 4. In what ways are younger generations more intelligent than older ones, according to cross-sequential research? 5. How do historical changes affect the results of longitudinal research? 6. How does cross-sequential research control for cohort effects? 7. What factors does Schaie think have significant impact on adult intelligence? 8. Why would a person want to be higher in crystallized intelligence than fluid intelligence? 9. Why would a person want to be higher in fluid intelligence than crystallized intelligence? 10. If you want to convince your professors that you are smart, what might you do and what intelligence does that involve? 11. If you want to convince your neighbors to compost their garbage, what might you do and what kind of intelligence does that involve? 12. What kinds of tests could measure creative intelligence? 13. What might a person do to optimize ability in some area not discussed in the book, such as playing the flute, or growing tomatoes, or building a cabinet? 14. How might a person compensate for fading memory skills? 15. How does the saying “Can’t see the forest for the trees” relate to what you have learned about adult cognition? 16. Think of an area of expertise that you have and most people do not. What mistakes do people make who are not experts in your area? 17. Two characteristics of experts—automatic and flexible— seem to work in opposite directions. Explain how an expert could avoid the problems of this polarity. 18. How specifically might intuition aid as well as diminish ability? 19. In what occupations would age be an asset, and why? 20. In what occupations would age be a liability, and why? Chapter Guide “On Your Own” Activities: Developmental Fact or Myth?; Portfolio Assignment AV: The Journey Through the Life Span, Program 8: Middle Adulthood; Transitions Throughout the Life Span, Program 21: Middle Adulthood: Cognitive Development Classroom Activity: -Problem-Based Learning: Cognitive Development During Adulthood Teaching Tip: Student-Generated Lecture Summaries I. What Is Intelligence? Instructional Objective: To help students understand the differences among the various methods of testing intelligence and to recognize that intellectual abilities can follow many different developmental patterns with age. AV: -Intelligence; IQ Testing and the School Classroom Activities: -Cohort and Intelligence; “Test-Wise” Bias 1. Historically, psychologists considered intelligence to be a single ability, what Charles Spearman referred to as g, or general intelligence. 2. For the first half of the twentieth century, researchers believed that intellectual ability rises in childhood, peaks during adolescence, then declines steadily as age advances. This belief was based on the results of cross-sectional research. 3. More recently, researchers have begun to doubt whether there is an inevitable decline in cognitive functioning with age. The longitudinal studies of Nancy Bayley and Melita Oden, for example, indicate that the IQ scores of Terman’s gifted individuals increased between ages 20 and 50. A follow-up study by Bayley found that the typical person at age 36 had improved on tests of vocabulary, comprehension, and information. 4. The earlier evidence of a decline in cognitive ability may be attributable to the shortcomings of cross-sectional research. Because it is impossible to match people in every aspect except age, cohort effects are inevitable. Longitudinal research also has shortcomings. People’s performance on tests might improve with practice. Also, some people leave the study; those who remain are usually the most stable, well-functioning adults. 5. Throughout the world, studies have shown a general trend toward increasing average IQ over successive generations. This trend is called the Flynn effect. 6. To correct for the limitations of the cross-sectional and longitudinal research methodologies, K. Warner Schaie developed the crosssequential research design for his Seattle Longitudinal Study. Each time his original cross section of adults was retested on primary mental abilities (longitudinal design), he also tested a new group of adults at each age interval and then followed them longitudinally as well, thus controlling for the possible effects of retesting, as well as uncovering the impact of cohort differences. Schaie’s results confirmed and extended what others had found: People improve in most mental abilities in adulthood. 7. In testing older Germans, Paul Baltes found that not until the 80s does every cognitive ability show age-related average declines. II. Components of Intelligence: Many and Varied Instructional Objective: To help students recognize that intelligence is multidimensional and practical. AV: Intelligence, Creativity, and Thinking Styles; MI: Intelligence, Understanding, and the Mind; Multiple Intelligences Classroom Activities: Fluid and Crystallized Intelligence; Sternberg’s Theory of Human Intelligence; Comparing Ideas About Intelligence; Classroom Debate: “Resolved: The Multidimensionality of Intelligence Makes Standardized IQ Testing Obsolete”; Intuition and the Intelligence of Everyday Life “On Your Own” Activity: -Measuring Creativity Critical Thinking Activity: Devising an Intelligence Test 1. In the 1960s, Raymond Cattell and John Horn differentiated fluid intelligence and crystallized intelligence. a. Fluid intelligence is flexible reasoning and is made up of the basic mental abilities such as inductive reasoning, abstract thinking, and speed of thinking required for understanding any subject. b. Crystallized intelligence refers to the accumulation of facts, information, and knowledge that comes with education and experience. 2. Fluid intelligence declines during adulthood, although this decline is temporarily masked by an increase in crystallized intelligence. 3. Robert Sternberg has proposed that intelligence is composed of three distinct parts: an analytic, or academic, aspect consisting of mental processes that foster efficient learning, remembering, and thinking; a creative aspect involving the capacity to be flexible and innovative when dealing with new situations; and a practical aspect that enables the person to adapt his or her abilities to contextual demands. 4. Practical intelligence, sometimes called tacit intelligence, is particularly useful in adulthood, when the demands of daily life are omnipresent. Interestingly, practical intelligence is unrelated to traditional intelligence as measured by IQ tests. 5. Which kind of intelligence is most valued depends on events in each person’s life, partly because of culture and cohort, and partly because of age. III. Selective Gains and Losses Instructional Objective: To provide students with a sense of the plasticity of intelligence and of how expertise develops. Teaching Tip: Expertise 1. A hallmark of successful aging is the ability to strategically use one’s intellectual strengths to compensate for the declining capacities associated with age. Paul and Margaret Baltes call this selective optimization with compensation. 2. Some researchers believe that as we age, our intelligence increases in specific areas that are of importance to us; that is, each of us becomes a selective expert in a particular area. 3. Research suggests that four features distinguish the expert from the novice. a. Experts tend to rely more on their accumulated experience than on rules to guide them and are thus more intuitive and less stereotyped in their performance. b. Many elements of expert performance are automatic. c. The expert has more, and better, strategies for accomplishing a particular task. d. Experts are more flexible in their work. 4. In developing their abilities, experts point to the importance of practice, usually 10 years or more and several hours a day before full potential is achieved. 5. Research studies also indicate that expertise is quite specific, and that practice and specialization cannot always overcome the effects of age. 6. Historically, research on expertise has focused on occupations that once had more male than female workers. Today, more women are working in occupations traditionally reserved for men. In addition, domestic and caregiving tasks that were once considered women’s work have gained new respect and are considered important when performed by both women and men.