A dynamical systems perspective on the self-system

advertisement

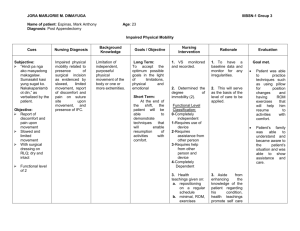

A Dynamic Systems Perspective on Arenas of Comfort, the Self-system, and Motivation Melanie J. Zimmer-Gembeck Carrie Furrer Ellen A. Skinner The ability to predict, and eventually optimize, adolescent development requires an understanding of the contribution of the contexts in which young people live, and especially how social interactions within those contexts shape development (Kindermann & Skinner, 1992). Today there is recognition of the multiple types and levels of contexts that exist simultaneously, all having the potential to influence individual development (Bronfenbrenner, 1977). Many developmentalists also expect that the contexts in which adolescents develop are dynamically related, hierarchically organized, interdependent, and that they serve co-regulatory and compensatory functions. The goal of this paper will be to describe a model of individual development that combines a dynamic systems perspective with two recent theoretical approaches – arenas of comfort (Call & Mortimer, 2001) and the self-system model of motivational development (Connell & Wellborn, 1991; Skinner & Wellborn, 1994). The original conception of arenas of comfort (Simmons & Blyth, 1987) highlights the benefits that are accrued when an adolescent is comfortable (i.e., at ease with self, high degree of fit with environment, moderate arousal) in some contexts and roles. Comfort experienced in one context buffers the effects of stress experienced in another context, thereby promoting adaptive developmental outcomes. The arenas of comfort concept emphasizes a social approach to the study of the self, coping, and development, but also contains motivational elements evidenced through the recognition that adolescents seek and select certain contexts to increase their comfort. The self-system model of motivational development also posits a transactional relationship between individuals and their contexts, which shape individual and developmental outcomes (Connell & Wellborn, 1991), but defines specific aspects of the context and the self that may be associated with comfort. This model proposes that particular contextual elements assist individuals in meeting three basic psychosocial needs. Viewing these two theoretical approaches from a dynamic systems perspective brings into focus the importance of understanding the dynamic exchange of resources between person and context, the organizing principles (e.g., higher-order needs) that structure such exchanges, and the development of both individuals and contexts as outcomes of system co-regulation. We will draw from the dynamic systems perspective and the self-system model of motivational development to extend the concept of arenas of comfort by making the elements of a comfortable context and the meaning of an adolescent’s experience of comfort more explicit, by forming empirically testable hypotheses regarding why some arenas are more comfortable than others both across and within developmental time frames, and by highlighting the dynamic reciprocity that exists between an individual and his/her multiple contexts. We will describe several propositions regarding organization, balance, interdependence, and compensation between contexts, and how such processes can have an impact on adolescent development and functioning. We will discuss potential links between arenas of comfort, stress, coping, resilience, self-perceptions, and optimal development, providing examples of how portions of this model were tested within the school context drawing from our study of the development of perceived control with the classroom (Skinner, Zimmer-Gembeck, & Connell, 1998). We will also propose empirical extensions to the peer domain (Zimmer-Gembeck, 1999). References Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward and experimental ecology of human development, American Psychologist, July 1977, 513-531. Call, K.T., & Mortimer, J.T. (2001). Arenas of comfort in adolescence: A study of adjustment in context. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Connell, J. P., & Wellborn, J. G. (1991). Competence, autonomy, and relatedness: A motivational analysis of self-system processes. In M. R. Gunnar & L. A. Sroufe (Eds.), Self Process and Development: The Minnesota Symposia on Child Development (Vol. 23). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, pp. 43-77. Kindermann, T. A., & Skinner, E. A. (1992). Modeling environmental development: Individual and contextual trajectories. In J.B. Asendorpf, & J. Valsiner (Eds.), Stability and Change in Development. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, pp. 155-190. Simmons, R.G. and Blyth, D.A. (1987). Moving into adolescence: The impact of pubertal change and school context. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine. Skinner, E.A., & Wellborn, J.G. (1994). Coping during childhood and adolescence. In D.L. Featherman, R.M. Lerner, & M. Perlmutter (Eds.), Life-Span Development and Behavior: Vol. 12. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Skinner, E.A., Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J., & Connell, J.P. (1998). Individual differences and the development of perceived control. Monographs of the Society for Child Development (Serial No. 254, Vol. 63, Nos. 2-3). Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J. (1999). Stability, change, and individual differences in involvement with friends and romantic partners among adolescent females. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 28, 419-438.