A STUDY OF A VERSIFIED TREATISE ON ARABIC GRAMMAR: RA

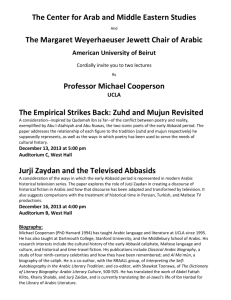

advertisement

A STUDY OF A VERSIFIED TREATISE ON

ARABIC GRAMMAR: RA'IYYATU 'LCRAB

Zakariyau I. Oseni

Introduction

Arabic grammar is a well-developed branch of Arabic

Studies. Right from the time of Prophet Muhammed,

attention has been paid to the grammar of the language as a

means of understanding the Glorious Qur'an. This is

because a small mistake in Arabic may change the meaning

of a text radically. As time progressed, leading muslim

figures such as cAli ibn Abi ATalib, Abu '1-Aswad alDu'ali, Ziyad idn Abihi and others contributed immensely

to the study and codification of Arabic grammar.1

Basic grammatical rules were explained, standardised,

illustrated and studied. Two major schools of grammar,

Basran and Kufan emerged. As more and more people

recognised the central role of grammar in the proficiency of

Arabic, more grammarians devised new methods of

imparting the knowledge of the subject to learners. One of

the new methods devised probably during the postcAbbasid period was versification. Some grammarians

wrote mneomotechnic verse on grammatical rules. Once a

verse or a couple of verses is read, the relevant rule would

become manifest. Some of such authors are Ibn Malik and

Abu 'IQasim ibn cAli al-Hariri.2 In Nigeria, cAbdullah ibn

Muhammad ibn Fudi wrote another one specifically on

morphology (Sarf) 3D, and of course, we have also the

treatise under study among others.

74

Ra'Iyyatu 1-1 crab is a shori treatise on grammar by a

Nigerian author, cAbdullah ibn Muhammad, a relatively

new scholar. 4 This paper examines this grammar work

which is popular among some old generation scholars of

Arabic and Islamic Studies scattered all over Nigeria.

Studying this treatise is important in many ways. First, it

will familiarise more scholars, especially those exposed to

a systematic mode of education of the Western type, with

the work which is at present known only to a selected few

of the old crop of scholars. Secondly, the present study will

explain to the reader the scope of the treatise and the

method employed by the author in imparting the knowledge

of grammar to students by versification.

This paper illustrates the work in its Arabic original as well

as in the English translation of it. In addition, the basic

copies covered in the work are explained. The aim of the

author expressed in the. opening verse is critically

examined vis a-vis the content of the work. One would like

to know how central the topics treated are in Arabic

grammar. The adequacy or otherwise of the illustrations

given in the work is also looked into.

75

76

77

The English Translation of Ra'iyyatu '1-lcrab

It is an R-rhymed poem on Desinental Inflection.

1.

O you who seek to know about dcsinental inflection,

before you is a

synopsis of its particles which I

have composed in verse.

2.

It teaches you dcsinental inflection and it is easy to

understand, well arranged inverse and I have thoroughly

simplified it for you.

3. (they are) thirty-eight verses in all which you should

take care of for they will teach you in a day what you

would (otherwise) be taught for a month.

4.

Min and ila are two prepositions as in: "The book

was from Hind to Bishr."

5.

So also are cAn and cnlo prepositions too, e.g. "Go on

and when you get to cAmmar, ask him about cAim"

78

6.

So also are mbba as well as the waw and la' of oath

and the kaf which is also a particle for lashbih (simile).

7.

You should ask for the remaining prepositions, for I

have shortened my speech based on the resolution to he

brief.

8. An is one of the particles that put the verb in the

accusative as far as we are concerned, e.g. "I hope lo

prosper at the sage's presence."

9

Kayla and kay are part of them, {as in) "Visit me so

that I impart to you some knowledge which no one can."

10. So also are fort, idhan, liana, \hclam of explanation

and the lam of denial.

11. As for the jussi particles they are many; I will give

you the most important ones among them.

12. lam, alam, hmma, man and ma e.g. "Abu Bakr has

not understood my speech."

13.

Of them loo, are mata ma, ayna. aynama, ayyu, the

lam of prohibition as well as the lam of command.

14. Abu 'IQasim the grammarian has stated that the parts

of speech are three in the beginning of (his) poem.'6

15. They are the noun, verb and particle which convey

meanings; what a splendid thing had been said by al-Fihri 7

79

16. Qama (he rose, stood up) and yaunu (he is rising,

standing) are verbs; as for the nou, it is everything that has

a reflection e.g. al-dar (the house), al-thawb (the cloth),

and al-dun- (the pearls).8

17. As for verbal nouns, they are al-qiyam (standing,

stand) and its like, while particles are *an, min, and 'Ha.

18. Grammarians put the subject in the nominative case

e.g. the Muezzin has announced the time of Midday Prayer.

19. With us (grammarians), the object is put in the

accusative by the verb, e.g. "leave Zayd, for he has come up

with an excuse."

20. If an object is presented without a subject, it should

be in the nominative, as argued by scholars.

21. An example is "Muhammad's child was not beaten,

and Zayd was not given his due by Abu cAmr."

22. Whenever a noun is put in construct with another

noun, the latter should be in the genitive case thus say the

grammarians in famous books.

23. An example is "This is the slave of Zayd please sell

to him, and he would give you one dinar at the end of the

month."

80

24. whenever a noun is joined to a definite noun (by a

conjunctive particle) its declension must agree in the

nominative, accusative or genitive.

25. An example is "Honour Khalid and Muhammad, and

be good to Zayd and “Amr for ever."

26. "Zayd, cAmr and jacfar came to me on horses with

radial blades."

27. So also do the adjective, the emphatic and the

permutative should be treated in declension like nouns in

the conjunction: please, keep the company of the intelligent

ones.

28. With us every noun in the vocative should be in the

accusative, with the exception of the definite singular noun

- do listen to my admonition.

29.

For example, "G cAbbad, deliver my trust and O

Yusuf, keep the secret with you."

30. The noun in the vocative, when in construct phrase,

should be in the accusative, e.g. "OAbda '1-Karim, carry

out my order."

31. Except the indefinite vocative, nouns intended for a

message should be in accusative like e.g. "O man, news has

reached me."

81

32. The rule governing the undefined noun is also

accusative, as in "O man you have won the pearls."

33. Grammarians put nouns in the beginning of

sentences in the nominative, e.g. "Zayd is an intelligent

scholar and a reciter (of the Our'an)."

34. If the predicate is a noun, you should put it in the

nominative. Do understand and never be tired of learning

and reflecting."

35. And be generous with prayer for Muhammad's son as

he had been generous with teaching you grammar in verse.

36. The not-too-intelligent spoke in order to attain

nothing but the pleasure and

pardon of God.

37. I beseech You, O the Benevolent, grant me the

pleasure of its use and relieve me-of burdens.

38. May our Lord accept your prayer, O my brother, and

ours too, by granting us pardon with thanks to Him.

A Critique of the treatise

Having given the Arabic and English versions of the

treatise, I shall begin this critique with a highlight of the

contents of the work. The treatise contains only 38 lines

'rhymed in letter ra' hence it is called an R-rhymed verse on

Desinental Inflection.

Lines 1-3 form the introduction in which the author

states (boasts?) that he would teach one within a day what

one should learn in a month. Bearing in mind the difficulty

82

often encountered by students of Arabic grammar, the

author talks about simplifying the work thoroughly.

Lines 4 -7 are on prepositions. In this section only,

eight prepositions, namely min (from), ila (to), can (about,

from), ca/a (on, above), waw (of oath), ta' (of oath) and kaf

(of comparison) are given. Thereafter the author asks his

reader to inquire about the remaining prepositions."

Lines 8-10 are on the particles which govern the

subjunctive. Here we have an (to), Kayla (so as not), kay

(so that), lan (never), idhan (then, therefore, in that case),

hatta (until), lam of explanation (so that), and lam of

denial. This is fairly comprehensive.

Lines 11-13 are on the particles and nouns which

govern the apocopate from, (al-jawazim). They are

basically sixteen in Arabic but only eleven are given here some of them being secondary forms of the basic ones.

Those mentioned are lam (not), flam (not), lainina (not

yet), man (who), ma (what), matama (whenever), ayna

(where), aynama (wherever), ayyn (which), lam of

prohibition/admonition/entreaty, and lam of indirect

command.

Lines 14 - 15 are on the three major parts of speech

in Arabic: the noun, verb and particle. In fact, each of these

three can be broken into several other parts of speech as

understood in English, for instance;10 I must state here that

lines 14 and 15 ought to be at the beginning of the treatise

immediately after the introduction. Bringing them there

creates a problem for the learner especially if he is a

beginner.

83

Lines 16 and 17 talk of the verb and the noun,

especially the verbal noun (tnnsdir) as well as some

particles. The two lines complement lines 15 and 16.

Lines 18 and 19 treat the subject of a verbal sentence (fail)

and the direct object of verbal .sentence (maful)), which

must take the nominative and accusative respectively. The

two lines are very fascinating in their Arabic original.

Lines 20 - 27 contain a number of grammar topics,

including the passive (al-majhul.) and the case of its

"surrogate subjects", i.e. the object whose subject is

omitted. Others arc the construct phrase (al-idafnli),

conjunction, and the adjective (al-nact). As usual, examples

are given to illustrate each topic.

Lines 28-32 are on the vocative (al-munada). The

various types are illustrated with examples. They are (a) the

definite singular noun (which should be in the nominative);

(b) the first word in a construct phrase (which should be in

the accusative case when preceded by the vocative panicle

m); (c) an indefinite non-intimate noun (which must be in

the accusative case); (d) the indefinite intimate or intended

noun (which should be in the nominative case). As usual

examples are given.

Lines 33 and 34 treat the subject and predicate

which are nouns. They should both be in the nominative

case.

Lastly, line 35 - 38 contain prayers. Ibn Muhammad

asks his readers to pray profusely for him for teaching them

grammar in verse. He states his aim in writing the work; the

quest for God's pleasure. lie also prays for himself and his

readers. This last Aspect reveals the major factor which

84

motivated many Islamic and Arabic scholars to write

books. That factor is the need for God's mercy and pleasure

since the writer believes that he is exerting himself to

benefit people, both far and near.

In the introductory section of the treatise, certain

claims are made by the author. He promises to teach

aspects of grammar in Arabic in a thoroughly simplified

manner. In addition he claims that he would teach his

students within a day what they would have laboured for a

month to study. The question now is: how realistic is that

claim in view of our clear grasp of the content of the

treatise?

To begin with, the treatise is brief and touches only

a few aspects of elementary grammar. Many basic elements

of grammar such as the different classifications of verbs,

different classes of objects, kana, inna and zanna and their

respective associates are not laugh! at all. Nothing is said

about the diptote (ma la yansarif), which is very basic in

this type of work.!1

The claim in the opening verses is, therefore, not tenable as

it has not been justified practically by the author. At best,

the treatise is a revision work for those who already know

key grammatical terms in detail, and not a concise treatise

to teach novices Arabic grammar in any special manner. In

fact, there is nothing said in the Ra'iyyatu 1-Icrab which'

Abu '1-Qasim al-Basir to whom our author also refers with

deference did not say in a more comprehensive manner

consequently ii is not right to claim that the work would

leach one within a day a month's academic work. Perhaps,

85

this is one of those familiar pretensions by scholars in an at

tempi to 'sell' their works.

The treatise is in the form of fia/ir al-'i'awil, one of

the most famous metres in Arabic prosody. It is a metre

reserved in most cases for lofty and sublime poetry. Ir) a

versified academic work such as his, Bnhr al-Rajoz is often

used because it is very flexible and does not neccssitme a

rigid mono-rhyme formula. Using Balir al-Tawil and

maintaining the R-rhyme throughout shews that the

composer is not a novice in the art of composition.

It is pertinent 10 highlight here the heavy reliance

on personal names in ending in "R" in the treatise. For

instance, the auihor uses Bishir (line 4), 'Amir (Line 5),

Abu Bakr (Line 12), al-Fihri, (Line 15) and cAmr (Line

21}. Such names provide cheap materials for the desired

rhyme letter "R". In a work of this nature, I must state that

there is nothing wrong with such a practice.

Important too is the tangible Islamic stamp on the

verse. Until about 1960 in Nigeria, Arabic studies had been

an exclusive area cultivated by Muslims alone. Arabic

helps interested people to explore and probe deeply into

Islamic sources and also places Arabic scholars in a special

position higher than that of their counterparts in Islamic

Studies who arc not sound in Arabic.13

One is not surprised, therefore, to notice a heavy

Islamic coloration in the treatise under study. The first one

is in line 18 where an example is given about a Muezzin

announcing to the Muslim the time for Zuhr (midday)

86

prayer. The second one is in the last four lines of the work

(lines 35-38). Notice how the erudite scholar begs his

students to pray for him and refers to himself as a dull man

who composed the verses only to seek the pleasure of God,

a servant who pleads fervently for God's pardon and prays

for his students too. This is a clear act of humility and

modesty. This type of statement in both prose and poetry is.

commonplace in the Arabic literature of West Africa,

especially the Jihad literature of Nigeria. It is in most

poems written by cAhduliah ibn Fudi, his contemporaries,

and those who came after him.14

As is common with Arabic and Islamic scholars in

Nigeria and elsewhere, anxiety and zeal to acquire

knowledge are of primary'' importance in life, hence the

relish with which [hey learn and teach at Zarnuji’s ta clim...

which is a book on Islamic education. ''This'bookish'

attitude is discernible in the treatise understudy.

Interwoven with their deep love for knowledge is

the consciousness of Islamic ethnics. In the examples given

in the treatise, there are some references to aspects of

Islamic ethics couched in direct and indirect advice to

readers or students. They are as follows:

1

Leave Zayd for he has come up with

an excuse" (Line 19).

c

2"Zaycl was not given his due by Abu

Amr" (Line 21).

87

3.

(Line 29).

"O Yusuf, keep the secret with you"

4.

"O Abcla '!-Karim, carry out my

order." (line 30).

The substance of the above statements is largely in

line with Islamic ethics. I believe that this type of

illustration is in line with modern methods of education. To

me, it is one of the most outstanding achievements of the

author.

Conclusion

It has been observed in the foregoing pages how a Nigerian

scholar cAbdullah ibn Muhammad treated selected

grammatical topics in his 38 line treatise. Even though his

work is not outstanding in pedagogical versification, it is

nevertheless a good attempt. In spite of certain

inadequacies in it, it serves a very useful purpose as a

revision work for learners of Arabic grammar.

Each of the examples given to illustrate the topics

bears testimony to the fact that the writer has a good

knowledge of grammar in addition to his ability to compose

in verse. Given the conservative and intricate nature of

Arabic prosody, an average student of Arabic knows that is

not easy to compose an elegant poem, especially in the

traditional sixteen metres in Arabic, more so in a non-Arab

milieu. I am aware thai there are many works of similar

88

nature in manuscripts in Ibadan, Jos, Kaduna,etc. It is

hoped that more research will be carried out on Arabic

grammar works of Nigerian, origin. The edition, annotation

and publication of such works will further ihe'

understanding of Arabic grammar and literature as well as

Arabic and comparative linguistics. This is a task from

which Arabic scholars in Nigeria and West Africa in

general cannot shy away. *

Notes

1.

For details, sec Dawud a!-cAilar, Mujaz cUlttm alQur'an. Teheran. Mu'assasat al-Q'an al-Karim, 1403 A.M.,

pp-185-90; Z. I. Oseni, "An examination of al-Majjaj b.

Yusuf al-Thaqafi's major Policies", Islamic Smdies, Vol.

27, No. 4, Winter 1988 Islamabad, pp. 38-20; M. A. Muazu

"Al-Dama'ir wa isticmalatuha fi al-Qur'an al-karim, Thesis

for Ph.D programme in Arabic (Ilorin, Department of

Religions, University of Ilorin) Sept. 1988, pp. 21-44; and

al-Munjid al-Aclam. (Beirut, Dar al-mashrkj, 1973) p.464.

2.

The two works are:

(a)

Muhammad ibn malik, Alifiyyah on which

numerous commentaries have been written. One of such

commentaries is Shark Ibn cAqilcak Alfiyyali Ibn Malik ed.

by Muhammad Muhyi 'l-Din cAbdu! 'I-Hamid. Vols I & II.

(Beirut, dar al-Fikr, 1972).

(b)

Abu'l-Oasim ibn cAli al-Ilariri al-Rasri, Miilhat allc rab. (Jiddah; As'ad Muhammad Sa 'd al-Hibal, n.d.). The

89

MS. of this book is in the national Museum, Jos

JM/A.M.S./125.

3.

See cAbdullah ibn Muhammad ibn Fudi, Al-Hisn alrasin fi clim al-Sarf (Beirut, dar ai-Fikr, n.d.).

4.

See Adam cAbduIlah al-Iluri, Sharh Ra ‘Iyyati + iIc rab (Cairo, AJ-Mashhad

al-llusayni, 1363 A.H)

5.

See Abu 'l-Qasim al-Hariri, op. cit (note 2 above). He

is the famous al-jjann who wrote al-Mnqamai.

6.

Al-Fihri here refers most probably to al-Hariri.

7.

The canopy referred to here is probably the definite

article (al).

8.

For details on common grammar topics, sec AlSanhaju, Main (il-Ajurumiyyah. (Cairo, Mustafa al-Babi,

1955); eld al-Wasif Muhammad, Al-Tuhfat al-Sanniyyalt:

Sharh al-janiyyah. (Cairo, Mustafa al-Babi, 1938); David

Cowan, Modern Literary Arabic (London, Cambridge

University Press, 1975); A. S. Tritton, Arabic. (Teach

yourself Books. (New York, David Mckay Co. Inc. 1973);

J. A. Haywood & H. M. nahmad, New Arabic Grammar of

the Written Language. (London: Lund Humphries, 1965); I.

A. B. Bolaghun & Z. I. Oseni, A Modern Arabic Course :

Books I - III, (Lagos : Islamic Publications Bureau, 1982

and 89; and Y. Mohammed & M. Haron, First Steps in

90

Arabic Grammar. (Pietermariizburg, Shuter and Shooter

1989); etc.

9.

For example, what is referred to as the noun (al-ism)

here can be broken into personal pronouns, demonstrative

pronouns, the active participle, the passive participle, the

adjective, the permutativc, the verbal noun, nouns of

instruments, nouns of place or lime, adverbs of manner,

place or time, etc.

10.

See Note No.9 above.

11.

See line 14 of the treatise under scrutiny.

12. See I. A. Ogunbiyi, Of Non-Muslim Cultivators and

Propagators of the Arabic language. (Inaugural Lectural

series). Lagos, Lagos State University, 1987), 31 pp. See

also "The Communique of the national Conference on

Arabic Studies in Nigeria and Higher Education: Problems

and Prospects", 4th - 6th October. (Kano, Baycro

University, 4th - 6th Oct., 1987), 300.

13.

See ine following, for instance: cAbdul!ah ibn

Muhammad, Tazyin al-Waraqat ed. M. Hiskeit. (Ibadan:

Ibadan University Press, 1963; cUthman A. Yususf

Eleyinla, Al-hikmah // al-SIiicr (Ijebu-Ode, Shebiolime

Publications 1987); Shams al-Din Muhammad alBadamasi, Al-Qasidah al-Mnkhamtnasah fi madh al-Nabi.

(Kano, cAbduIlah al-Yassar, 1962); cUthman b. Fudi, Hal

!i Mnsir, (Kano, cAbduIlah al-yassar, 1962); and Sambo

91

W. Hunaid, "Al-Madh al-Nabawi', a poem published in

NATAIS:

Journal oft/ie Nigerian Association of '/'caches of Arabic

and Islamic Stmhc.-. Vol. II, No. I Dec. I9«)pp. 132-33.

14.

The full particulars of this famous hook in Nigeria

are: Burhan al-Islam al-Zarnuji.arnuji, Ta dim almutacallim tariq al-tacalhtm. (Cairo, Mustafa al-babi,

1948/1367.

15.

Public institutions where many of such works arc

kept included the Centre for Arabic Documentation.

University of Ibadan, University of Ibailan Library,

National Museum, Jos, National Archive, Kaduna, etc. and

the private libraries of prominent scholars all over Nigeria.

92