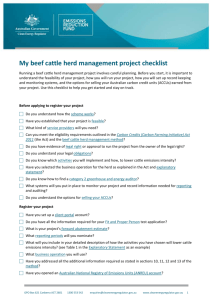

Wild Cattle

advertisement

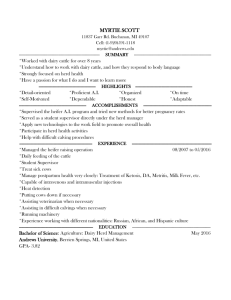

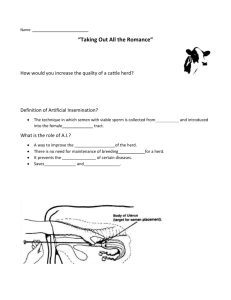

Wild Cattle in Britain The Chillingham Herd A. Karlsson, VEGA Research 2007 Figure 1: Chillingham cattle, picture from http://www.whitepark.org.uk/chillingham.htm. Domesticated cattle Cattle are domesticated ungulates, a member of the subfamily Bovinae of the family Bovidae, a family that also includes e.g. goats, sheep, bison and antelope. Domesticated cattle are raised for meat, dairy products, and leather, and to be used as draught animals (pulling carts and plows). The word cattle derives from the Latin caput (head) and means unit of livestock or one head. There are 3.8 million dairy and beef cattle in the UK (figures from 2005). Including younger calves and heifers, the figure is about 10.4 million. There are two different domestic breeds of cattle; Bos indicus (zebu) and Bos taurus (taurine), differentiated by the presence or absence of a hump, and they both derived from the aurochs, Bos primigenius. Bos indicus occurs mainly in tropical regions and Bos taurus mainly in temperate regions. Recently the two breeds as well as the aurochs have been grouped as one species, with the subspecies Bos primigenius taurus, Bos primigenius indicus and Bos primigenius primigenius. The dairy cattle in the UK today are mainly Friesian/Holstein. The use of artificial insemination has contributed to the higher production levels of these cattle. Figure 2: Aurochs, picture from the Natural History Museum. There are two theories of how the aurochs became domesticated. One theory is that the two domesticated breeds mentioned above originated from the same species 8,000-11,000 years ago. The second theory is that the two breeds originated from two subspecies of the aurochs in different locations. Examination of DNA (Loftus et al. 1994) showed that there are two distinct lineages, one European (taurine breeds)/African (a cross between zebu and taurine breeds) and one Indian (zebu breeds), supporting the theory that the domestication occurred in different locations, and the domestication could have happened 200,000 to 1 million years ago. Aurochs in Britain became extinct during the Bronze Age (2200-700 BC), but these aurochs had no genetic contribution to Britain’s domesticated cattle. Modern European cattle are thought to be descended directly from the domestication of the aurochs in the Near East mentioned above. The last aurochs were killed by poachers in Masovia, Poland, in 1627. Human breeders have attempted to recreate the species by crossing commercial breeds, creating the Heck cattle breed (see picture below). Figure 3: Heck cattle, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Heckrund2.JPG. The closest living relatives of the domestic cattle are bantengs, Bos Javanicus, and gaur, Bos gaurus, in South East Asia. Bantengs are endangered and the world population is unlikely to be more than 8,000 and could be fewer than 5,000 animals. Gaurs are classified as vulnerable, and there are an estimated 13,000-30,000 left. Both bantengs and gaur are threatened by hunting, loss of habitat, disease transmission from domestic cattle, and interbreeding with domestic and semi-feral cattle. Like many other horned mammals they are valued by humans for their horns. Bantengs and gaurs form small herds of 10-30 individuals. Dairy cattle in the UK have an average herd size of 70, although sometimes there can be up to 150 individuals in the same herd. In the wild, several herds of bantengs or gaurs may get together during breeding season. Young males often form bachelor groups. There is a strict social hierarchy in a herd based on matriarchal families. The highest ranking individual has priority to food, shelter and water, and the offspring inherits its mother’s status. Calves often form lifelong relationships when only a few days old, and the social bonds are reinforced through mutual grooming. A new member or separation of a herd is very stressful to the herd. Cattle have poor depth perception and they are therefore reluctant to enter dark or shadowy areas and they also react to e.g. changes in floor surface and shadows. They have good hearing, which is superior to humans’ hearing, and cattle are sensitive to loud, sudden noises. Gaur (from WWF) Banteng (from WWF) The colour of cattle is due to its origin, but also to genetic modification; e.g. the Celts thought red animals symbolised fertility and crops, black animals pestilence and death, and white animals the worship of the sun (Alderson 1992), which might have lead to selective breeding of the cattle to produce these colours. Britain’s wild cattle Animals (human and non-human species) have colonised and re-colonised Britain several times in the past, maybe from as early as 500,000 years ago. Due to several glaciations most species have had to move south from Britain several times to avoid the cold and the glaciers. One of these glaciations was the last major cold event, which peaked around 18,000 years ago. Britain was then connected to the continent. Further fluctuations in the climate followed, before the current warm phase (the Holocene) began about 10,000 years ago. Humans and large land mammals, including wild cattle, crossed the land bridge before Britain was disconnected from the mainland. Today, there are six “wild” cattle herds in Britain; the Chillingham, Vaynol, Dyneros, Woburn, Whipsnade and Cadzow herds, but not all of them are wild or purebreed anymore since most of them are domesticated to some extent. The Chillingham herd is considered to be truly wild as they have been isolated in the Chillingham park for 750 years with little human interference. . Figure 4: The Chillingham cattle in the Chillingham park, from Hall et al. 2005 The Chillingham herd The Chillingham cattle are white cattle, remnants of Britain’s wild cattle. The herd of 57 individuals resides in a 365-acre park, the Chillingham Park (link to http://www.chillingham-wildcattle.org.uk/Visitor_Information.htm#Map), in Northumberland, northern England, owned by the Chillingham Wild Cattle Association (CWCA), a registered charity. This park was enclosed in 1270 AD and the cattle have been isolated from other cattle and from most human interference since then (there is as little contact with humans as possible). The park is open (link to http://www.chillinghamwildcattle.org.uk/) to the public, but visitors must be accompanied by a warden. Other species that can be seen in the park are e.g. roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), fallow deer (Cervus dama) and several bird species, as well as tree species such as alders (Alnus sp.), beeches (Fagus sp.) and oaks (Quercus sp.). There are also 300 breeding ewes in the park. The total stocking density of the park is 0.48 livestock unit per hectare. The isolation of the Chillingham cattle means that for the last 750 years the herd has had no contact with other cattle. This isolation and the small size of the population in the past have lead to inbreeding, creating a genetic bottleneck. (A genetic bottleneck is when there are few individuals left in a population and the population experiences a decline in genetic variability over time. Genetic bottlenecks can have devastating effects on the variability and fitness of a population). The Chillingham herd is almost genetically uniform, but there seems to be no reduction in fertility so far. The small population size of the Chillingham cattle has most likely brought about the cattle evolving into a smaller size. An adult Chillingham cow weighs 280 kg on average, compared to American bison, Bison bison, 1360kg and domestic cattle 300400kg depending on species. Chillingham cows will mature at the age of 4 years while bulls will mature at the age of 18-20 months, and life expectancy is 17 years for cows and 13 for bulls. This is compared to American Bison, 18-22 years (or 35-40 years in captivity), and other cattle, 20-50 years depending on the species, although e.g. a dairy cow will live for 4-7 years before worn out and slaughtered, ending up as meat for hamburgers. The herd is a rare opportunity to study the natural behaviour of cattle practically free from human interference. The herd is one of a few cattle herds in the world that has a natural sex ratio and age distribution. Most other cattle are farmed animals; slaughtered at an early age. Roughly one fourth of the Chillingham females will have a calf each year, see Error! Reference source not found. below. The cows will calve away from the herd, and the calf will be introduced into the herd and initially greeted by the King bull; the dominant bull in the herd and the only bull that mates with the cows. A dam will suckle her calf 4-6 times a day, while a dairy cow will be milked twice a day. Female calves will suckle until they are nine months old and stay with their mothers for life. Males are weaned at 12 months old. In modern day farming the calves of dairy cows will be taken from their mothers after 1 or 2 days. Cattle, if they are allowed to, would spend 4-14 hours grazing and 9-12 hours lying down. The Chillingham herd will graze during summer around dusk and dawn and during mid-morning and early afternoon. During winter there might be some night-time grazing. The cattle can graze up to 3h at a time and females graze longer than males in summer. The Chillingham cattle are white with red-brown ears and markings and black spotting on the shoulders. They never seem to have calves that are any other colour, or even partly coloured. All animals have horns. Figure 5: Chillingham calves, from Hall et al. 2005. There are records of the size of the Chillingham herd dating back to 1692 and the largest numbers were 80 individuals in 1838. In 1947, due to a severe winter and previous droughts leading to a lack of fodder, only 13 individuals survived. However, as of 2005 the numbers are 57. In 1968 there was an outbreak of Foot and Mouth disease in Northumberland. The disease never reached the Chillingham herd, but after this threat a small reserve herd (currently of 12 individuals) was set up near Elgin in north-east Scotland. Some welfare implications in the herd are calving difficulties and abandonment of calves. Several cows died due to magnesium deficiency in the early 1980s. Therefore, magnesium limestone has been applied to 6 ha of land each year. Bracken cutting has been carried out since 1992 to increase the supply of herbage. The Chillingham cattle have been fed hay in the winter since at least 1721, this is because the cattle cannot roam freely outside the park to seek out enough food to survive the winter. The hay is purchased from an organic local farm. The cattle are also fed compound feed approved by the Soil Association in winter to try to improve the nutritional status of the calves. The cattle usually don’t go under cover or seek shelter. The nearest outbreak of the Foot and Mouth disease in 2001 occurred 10km from Chillingham. In the event of a future outbreak, vaccination could be an option under an EU Directive, although CWCA has concerns of the handling of the animals as well as the possible risks of a vaccine in these homozygous cattle. There is no evidence of any notifiable diseases in the herd and the cattle has never been identified with tuberculosis (an animal health problem currently facing the farming industry in Great Britain, see http://www.defra.gov.uk/animalh/tb/index.htm). Hall et al. (2005) thinks the homozygosity of the herd might make it highly vulnerable to disease, although other sources suggest the homozygosity could make them more resistant. This would probably depend on the genes and the disease. Since 1950 some diseases have been investigated in 64 cattle that have had a post-mortem examination. Table 1: Diseases investigated in the Chillingham herd Disease investigated Disease found Cause of death Similar disease in domesticated cattle Histological evidence of mild Johne's disease, 1963. Johne's disease, 2005. Bovine tuberculosis not observed Johne's disease in 2005 Johne's disease is an infectious condition caused by Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis. The disease results in diarrhea, severe weight loss, and infertility. It is notifiable in Northern Ireland but not in the rest of the UK. Estimates of herd prevalence of 1% and 17.5% in the UK Dystocia 1945 - February 2005 Cause of death of 8 cows or heifers (1.8% of calvings have resulted in the death of the dam) 5 % of births in dairy cattle, assistance with calving needed Ectoparasites Haematopinus eurysternus No obvious louse (louse), 1977 infestation Endoparasites Worms found: Ostertagia Ostertagia and Dictocaulus sp. sp., 1983 Trichostrongyles In calves mainly in summer No evidence of parasites in sp., 1983 Cooperia sp., months in their first grazing post-mortem 1983 Fascioliasis sp., 1963 season, and sometimes in the & 2005 later winter months Bacterial diseases Hypomagnesaemia 1980. Symptoms: high excitability, falling over with spasms in the legs, death due to heart failure Neoplasias Intraocular melanoma with secondaries to the liver, 2002 Ocular disease New forest disease widespread in the herd in the late 1970s Skeletal and dental defects Calf born without a tail, 1999 Cause of death of 6 lactating cows Can cause hair loss, irritation and loss of body condition in housed cattle at any age Mainly in animals on spring grass (low in Mg content) and occasionally on autumn grass (foggage or fog fever: when hungry cattle that have been on dry feed for some time are allowed free access to rapidly growing, lush green feed) New forest disease is an infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis, a group of eye diseases of cattle which can lead to impaired vision or blindness if left untreated. Causes can be bacteria, viruses, fungi and Commonly associated with worms. It can be successfully trauma and secondary treated and cleared up bacterial infection overnight. Signs of the disease are runny and sore eyes with ulcers in the eye surrounded by a red area. Flies can spread the infection. One prevention is to use eartags impregnated with insecticide to help control fly infestation Testicular hypoplasia In yearling bulls Trauma 1945 - 2005 Cause of death of 14 bulls and females due to injuries caused by other members of the herd Trauma is the cause of injury in domestic cattle due to e.g. overcrowding, stress and long transports Possible threat of public access to the park The Right to Roam (http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/3651482.stm) under the CROW Act 2000 (Countryside and Rights of Way http://www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts2000/20000037.htm) gives access of open country and registered common land to the public. The Chillingham Wild Cattle Association (CWCA http://www.chillingham-wildcattle.org.uk/) has submitted a formal application to have the park closed to public access (under Section 25 (http://www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts2000/00037--d.htm#25) of the Act relating to public danger), and is awaiting a decision on this. There are several articles about the Chillingham herd in our database, available from our home page. Links, sources and further reading Chillingham Wild Cattle Association (hyperlink) http://www.chillinghamwildcattle.org.uk/ was formed in 1939 to take care of the herd. Another charity, the Sir James Knott Charitable Trust, owns the land and has leased the grazing rights to the Chillingham Wild Cattle Association for 999 years. Opening times are 1 April until 31 October: Monday-Saturday (excluding Tuesday) 10am-12 noon, Monday-Sunday (excluding Tuesday) 2pm-5pm. See website for up-to-date opening times. admission prices and a map (http://www.chillinghamwildcattle.org.uk/). Sir James Knott Charitable Trust Brigadier J.F.F. Sharland Secretary Sir James Knott 1990 Trust 16-18 Hood Street Newcastle-upon-Tyne NE1 6JQ Chillingham Wild Cattle Association The Secretary Chillingham Wild Cattle The Warden's Cottage Chillingham Alnwick Northumberland NE66 5NP Countryside and Rights of Way http://www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts2000/20000037.htm White Park Cattle http://www.whitepark.org.uk/ Chillingham cattle Hall, S. et al., 2005. Management of the Chillingham Wild White Cattle. Government Veterinary Journal 15(2): 4-11 http://www.defra.gov.uk/animalh/gvj/vol1502/gvj-vol1502.pdf Visscher, P.M., Smith, D., Hall, S.J.G. and Williams, J.L., 2001. A Viable Herd of Genetically Uniform Cattle. Nature 409: 303 http://www.era.lib.ed.ac.uk/bitstream/1842/690/2/Visscher_P.pdf Hall, S.J.G. and Hall, J.G., 1988. Inbreeding and population Dynamics of the Chillingham Cattle (Bos taurus). Journal of Zoology, 216(2): 479-493 abstract available at http://md1.csa.com/partners/viewrecord.php?requester=gs&collection=ENV&recid=1884 093&q=&uid=1310432&setcookie=yes History of cattle Alderson, L. The Categorization of Types and Breeds of Cattle in Europe. Archivos de zootecnia 41(154): 325 www.uco.es/organiza/servicios/publica/az/articulos/1992/145(extra)/pdf/lawrence_325_3 35.pdf (if not available as pdf try to get the html version from google) Cymbron, T., Freeman, A.R., Malheiro, M.I., Vigne, J-D. and Bradley, D.G., 2005. Microsatellite Diversity Suggests Different Histories for Mediterranean and Northern European Cattle Populations. Proceedings: Biological Sciences, 272(1574): 1837-1943 abstract available at http://www.journals.royalsoc.ac.uk/app/home/contribution.asp?wasp=a9930c26739d48c 099b4dc1966758c3e&referrer=parent&backto=issue,14,17;journal,2,204;linkingpublicati onresults,1:102024,1 Loftus, R.T., MacHugh, D.E., Bradley, D.G., Sharp, P.M. and Cunningham, P., 1994. Evidence for Two Independent Domestications of Cattle. PNAS 91: 2757-2761, http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/abstract/91/7/2757 Aurochs http://www.bbc.co.uk/nature/wildfacts/factfiles/3037.shtml Conservation status of wild cattle (a table showing increasing or declining trends in the different species) http://www.csew.com/cattletag/Cattle%20Website/Conservation%20Status/Conservation _Status.htm Farming Viva, 2005, The dark side of dairy, available from http://www.milkmyths.org.uk/pdfs/dairy_report.pdf UFAW, 1999. Management and Welfare of Farm Animals, Halstan & Co, Amersham Fraser, A.F. & Broom, D.M.,1990. Farm Animal Behaviour and Welfare. Balliere Tindall, London DEFRA, 2006. Stats 04/06: Agricultural and Horticultural census: June 2005, United Kingdom, available from http://statistics.defra.gov.uk/esg/statnot/june_uk.pdf Guar and Banteng WWF, undated, Introducing the Gaur and Banteng, available from http://assets.panda.org/downloads/10gafactsheete.pdf http://www.vegaresearch.org/animal_dairy.asp Stephen Hall, Lincoln Uni: sthall@lincoln.ac.uk Tel: 01522 895434