Texts:

advertisement

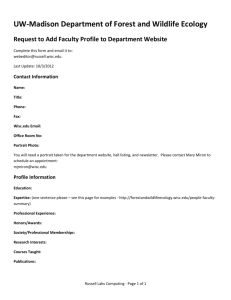

Course: Global Strategic Management, Class XIII Web: http://instruction.bus.wisc.edu/mcarpenter/ Instructor: Mason A. Carpenter mcarpenter@bus.wisc.edu (608) 262-9449 Summary: This is a five-week crash course in business, corporate, and global strategy – developing an understanding of strategy while exposing you to the challenge and rewards of negotiating your position as an opportunistic entrepreneur in a complex organization! Each block will provide you with information about (1) yourself, (2) fundamental perspectives in strategic management and global strategy, and (3) the interdependence of strategy formulation and implementation. The topics and concepts covered in each block are outlined below, and detail on your assignments are provided in the following pages. An integral part of the class will be the application of what you have learned throughout the program in an independent final project on your firm. Week One (Jan 12 & 13) Block 1 S1-Friday: Intro and Amgen Case S2-Saturday: Jeffrey Immelt Case Concepts An overview of strategic planning, strategy formulation and implementation Week Two (Jan 26 & 27) Block 2 S3-Friday: S4-Saturday IBP Case Copeland-Bain Case Delving into Business Strategy Week Three (Feb 9 & 10) Block 3 S5-Friday: Millennium (A) Case S6-Saturday: Wendy Simpson Case Developing and executing strategy through alliances Week Four (Feb 23 & 24) Block 4 S7-Friday: Masco & Household Furnishings Cases S8-Saturday: Cisco & Grand Junction Cases Developing and executing strategy through M&A Week Five (Mar 9 & 10) Block 5 S9-Friday: Cross-cultural simulation S10-Saturday: Dennis Hightower Case Grading: Experiencing cultural differences and bringing all the pieces of strategy together 55% Group Case Projects, 30% Individual written project, 15% Contribution. Text: Carpenter & Sanders. 2007. Strategic Management: A Dynamic Perspective + Cases. 1 Course: Global Strategic Management, Class XIII Web: http://instruction.bus.wisc.edu/mcarpenter/ Instructor: Mason A. Carpenter mcarpenter@bus.wisc.edu (608) 262-9449 Data Sheet Date Cases In Packet? Jan 12 Amgen: Planning the Unplannable (HBS 9-492-052) Yes Jan 13 GE’s Growth Strategy: The Immelt Initiative (HBS 9-306-087) Yes Jan 26 IBP and the U.S. Meat Industry (HBS 9-391-006) Yes Jan 27 Copeland Corporation/Bain & Company: The Scroll Investment Decision (Darden UWA-BP-0353) Yes Feb 9 Millennium (A) (HBS 9-600-038) Yes Feb 10 Wendy Simpson in China No Feb 23 Masco Corp. (A) & the Household Furniture Industry in 1986 (HBS 9-389-186 & 9-389-189) Yes Feb 24 Cisco Systems, Inc.: Acquisition Integration for Manufacturing & Grand Junction (HBS 9-600-015 & HBS SB186) Yes Mar 9 Cross Cultural Simulation No Mar 10 Dennis Hightower Taking Charge and Walt Disney’s Transnational Manager (HBS 9-395-055 & 9-395-056) Yes AND THAT’S MY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY, ANY COMMENTS? STRATEGY IT APPEARS TO BE A BUNCH OF OBVIOUS DIDN’T TURN OUT TO BE GENERALITIES AND WISHFUL THINKING THE GLAMOUR COURSE I WITH NO APPARENT EXPECTED BUSINESS VALUE I CIRCLED ALL THE WORDS YOU WON’T FIND IN ANY TEXTBOOK 2 Course: Global Strategic Management, Class XIII Web: http://instruction.bus.wisc.edu/mcarpenter/ Instructor: Mason A. Carpenter mcarpenter@bus.wisc.edu (608) 262-9449 Course Detail The pervasive theme of this course will be dynamic strategies for global firms. As a global strategist you will be responsible for understanding the fundamental aspects of business and corporate strategy, further complicated by the challenges of global and globalizing operations, markets, and competitors. We will also use this context to introduce you to the role of the expatriate manager, an entrepreneurial opportunist tasked with negotiating agreements within and across levels of the firm, across geographies, and across firms. For that reason, contexts that shed light on within- and across-firm negotiations will be a regular and integral part of the course, starting with the strategy implementation framework we study for session #2. Global strategy is more than analysis. To be sure, strategic analysis is a major part of this course, and we will explore and apply several analytical techniques for effectively positioning a firm or a business unit within a competitive environment. But strategic analyses are complicated by the trade-offs inherent in any situation. These trade-offs reflect the fact that organizations consist of many players with multiple, competing objectives. When dealing with tradeoffs, the strategist must confront the judgmental issues involved in establishing organizational purpose and balancing economic and non-economic objectives. Global contexts always appear to be rife with difficult-toquantify decisions. To the extent possible in each class, we will attempt to balance these trade-offs and to test our ideas about the appropriate relationship among them. Finally, global strategic management requires moving beyond analysis and trade-offs into the realm of strategic action. Once the analytical problem of selecting a strategy has been dealt with, we should know what to do, or at the very least know in which direction we will take strategic action and where and where not we will invest scarce resources. Knowing how to execute the selected strategy is essential to success. To the extent possible in each case, we will concern ourselves with the various combinations of systems (for example, information, control, reward, etc.), organization structures, and people necessary to execute a given strategy. We will test our ideas about the relationships between global strategy and these other elements as we proceed through the course. Performance Measures and Feedback Performance evaluation and feedback will be based on your performance in three different settings—team projects, a final individual project, and class contribution (which requires class attendance). In general, performance which meets my expectations earns an “A/B;” performance which surprises me (positively) and exceeds my expectations earns an “A.” Application of the assigned material to the case questions in a thorough, competent, and professional manner meets my expectations. Group Cases (55%) A portion of your grade is based on group presentations (weighted evenly on the substance of your recommendations and style points) and cases assignments. Length and other details on these assignments are provided in the particular session descriptions. 3 Course: Global Strategic Management, Class XIII Web: http://instruction.bus.wisc.edu/mcarpenter/ Instructor: Mason A. Carpenter mcarpenter@bus.wisc.edu (608) 262-9449 Final Individual Project (30%) This project involves conducting a strategic audit/competitive analysis of a firm chosen by you, preferably your firm. If you prefer an external target then go for it, but I expect the same high level of quality for each. Regardless, you should be sure to have a bibliography to identify your sources of data. In conducting your analysis, you may want to consider including the following: 1. Analysis of Industry Structure - Attractiveness of industry (Porter 5 Forces model) and related businesses along the value chain (Profit Pools Analysis) - Key success factors in the industry - Opportunities or threats - Relevant industry trends (customer, costs (technology), competitors, and government/trade) with implications for firm performance and strategy 2. Assessment of firm strategy (sources of competitive advantage, if any). - What would a map (using the strategy diamond) of your firm look like? - What is the firm’s generic strategy, if any? (e.g., cost, mass customization/value, differentiation)? o Cost strategy (cost structure analysis, value chain analysis, experience curve) o Differentiation strategy (customer segmentation, consumption chain) - What resources and/or capabilities does the firm have (or require) to successfully implement the strategy? - Assess the firm’s resources/capabilities relative to key competitors; do these make sense given the key success factors in the industry? - Identify growth options to access or acquire needed resources to grow organically or through cooperative strategy (horizontal or vertical alliances) or acquisition. 3. Analysis of firm scope -Vertical Scope (degree of vertical integration appropriate?) -Horizontal Scope (degree of product/business diversification appropriate?) -Growth options (acquisitions, alliances, internal) -Geographic Scope 4. Recommendations for future firm strategy/actions - Do you have recommendations for changes in firm strategy? Are there opportunities to employ a disruptive/revolutionary strategy? - Changes in strategy often involve a change in “what” the company is offering, “who” the company is offering its mix of products and services to, “how” the company is delivering value to the customer (methods and processes) or “where” the company chooses to compete. Changes typically relate to all five facets of the strategy diamond. - In your recommendations, have you taken into account possible competitor responses (strategic interaction). - Have you demonstrated the feasibility of your recommendations, in terms of laying out its implementation pathway? 4 Course: Global Strategic Management, Class XIII Web: http://instruction.bus.wisc.edu/mcarpenter/ Instructor: Mason A. Carpenter mcarpenter@bus.wisc.edu (608) 262-9449 Strategic Audit Evaluation Criteria As you prepare to conduct your strategic audit, I thought it would be helpful if I briefly explain what I consider when grading the strategic audit. I will then identify “common problems” 1. (40 percent) Did you make effective use of class concepts/ frameworks/models in your analysis of the company and its strategy and competitive position (Did you demonstrate that you understand when you should use particular concepts/frameworks)? Do you also demonstrate that you really understand the concept and use it to provide appropriate insights into the company’s competitive position?). How effective is your analysis of: a. Industry attractiveness (analysis of attractiveness, profit pools, trends, etc.) b. Firm strategy (resources/capabilities) and competitive position (analysis of marketshare position, cost position, resources/capabilities to meet key customer needs relative to competitors, etc.). How effective (and objective) is the analysis of company strengths and weaknesses in terms of VRINE? c. Firm scope (analysis of whether the firm has the appropriate vertical, horizontal, and global scope). 2. (25 percent) Do you provide effective quantitative (data driven) analysis to support assertions made throughout the paper? (Are there numerous unsupported assertions or are the assertions/conclusions always supported by data, theory or effective supporting arguments?) Are you creative in the way data are analyzed and displayed? Does the data analysis provide new insights? 3. (20 percent) Do you provide specific and useful (and hopefully novel, creative and doable) strategic recommendations for the company? (Or are the recommendations largely generic in nature? e.g., “they should explore an acquisition.”) 4. (15 percent) Is the paper well organized (does the logic flow cleanly from one section to the next)? Is the paper well-written (clear and interesting prose, no typos, grammatical errors etc.). Does it make effective use of graphics in the overall presentation of the analysis? Is the overall presentation professional? Does the paper sell your ideas? In the past I have found some common mistakes that students tend to make when writing their strategic audit. While I will not “preview” a paper, here are some suggestions that I have given students to help them strengthen their strategic audit papers: 1. Provide more effective quantitative, data-driven analysis to support assertions/ conclusions made throughout the paper. Comments would be made such as: “this is an attractive market,’ “the company is in a strong position,” “due to the company’s cost advantage,” “the cost of entry is prohibitive,” “the company has a first mover advantage” without providing data, quantitative analysis, or other analysis to support the assertions. What criteria were used to determine that the market was “attractive?” (size, growth, profitability of existing companies, lack of competitors?). If the cost is “prohibitive” then you need an analysis of the capital requirements to enter the market and then explain why that would be “prohibitive” for any viable new entrant. If you assert a cost advantage, then provide an analysis of the source of the cost advantage with your educated estimates 5 Course: Global Strategic Management, Class XIII Web: http://instruction.bus.wisc.edu/mcarpenter/ Instructor: Mason A. Carpenter mcarpenter@bus.wisc.edu (608) 262-9449 as to how large the cost advantage might be, and how much of an overall profit advantage this might create (as a percent of total cost or sales). Most papers would have benefited from creating a chart that looked at the relative profitability of competitors in the industry and the relative market share/experience. At least by showing the profitability of each key competitor (and by providing a brief explanation of the strategies of successful, and unsuccessful competitors) you might have been able to shed more insight into the key success factors in the industry. Finally, if you assert a first mover advantage, you must explain the specific source of the first mover advantage (just being first doesn’t necessarily provide an advantage; many second movers have defeated the market pioneers (e.g., Sony Playstation beat Atari, Microsoft OS beat Apple OS, Matsushita’s VHS VCR beat Sony’s Beta). You need to be precise in your explanation of why the 2nd mover cannot replicate the advantages of the first mover (e.g., Wal-Mart—Natural Geographic monopoly; eBay—Network effects, etc.). 2. Another common error was conducting a “5 forces + 1 analysis” at the firm level instead of the industry level. Remember, its called industry analysis because you are analyzing an industry, not the world through Wal-Mart or another industry player’s eyes. Conversely, students may analyze the industry without discussing the implications of the analysis for the firm’s strategy. If there is high buyer power (and a consolidating customer base) how can the company mitigate that high power? Should they attempt to consolidate their part of the value chain (through acquisitions or alliances), thereby increasing the market power of the remaining companies? Are there specific things the company should do to create switching costs? If currently rivalry is high, are there any actions the firm can take to reduce the amount of rivalry among competitors? What key complementors exist? The point is that it is critical to think through—and discuss—the implications of any analysis you do for the firm’s strategy. 3. Provide more creative and novel strategic recommendations. This is, arguably, the most difficult, and important part of the audit. It also often separates the excellent papers from those that are just good, since a strategy is useless if it does not foster profitable action. Again, recommendations that are generic (“they should explore acquisition opportunities”) are not helpful. Effective recommendations need precision and specificity to provide real substance (e.g., Krispy Kreme should establish an alliance with Starbucks, selling Starbucks coffee at Krispy Kreme locations and Starbucks selling fresh Krispy Kreme’s at Starbucks locations; then in big city markets they can establish a delivery service for company breakfast meetings, etc.). Moreover, if you recommend an acquisition, be specific about the target and the anticipated synergies (for example, just stating that an acquisition will provide cost savings and cost advantage isn’t nearly as helpful as analyzing the specific areas where cost will be reduced and providing an estimate of how the cost structure of the company will change after the acquisition (e.g., we anticipate G&A to drop by roughly 20 percent, sales and marketing by 10 percent, etc. for an overall reduction in costs of 3 percent). Of course, this would also require the supporting analysis. 4. Generally the analysis of the strengths of the company was pretty good, while some individuals tended to gloss over or minimize the weaknesses of the firm. When conducting this type of strategic analysis, it is important to focus on the company’s areas of weakness as much as its strengths. Audits tended to be very complementary about a company’s past strategic moves when it appeared that those moves led to the advantageous position being described. However, it’s also important to address the question of whether that advantageous position could be eroded through 6 Course: Global Strategic Management, Class XIII Web: http://instruction.bus.wisc.edu/mcarpenter/ Instructor: Mason A. Carpenter mcarpenter@bus.wisc.edu (608) 262-9449 imitation or other competitive moves. What if some generic entrant or competitor simply copied everything that seems successful about the focal company? Would that competitor be effective in eroding the focal company’s performance? In the face of such imitative attempts why would or wouldn’t the company be vulnerable? Pointing out and critically analyzing areas of weakness can be particularly helpful because most of us (as individuals or executives) tend to be a bit more blind to our weaknesses, or we don’t think we have a weakness when we really do. I hope these comments are helpful as you prepare your strategic audits. Best of luck! Contribution (15%) I expect each of you to take responsibility for the learning effectiveness of our sessions – this means that the class as a whole will have learned more because of your comments and questions. Moreover, the course is somewhat unique in that most of the actual learning takes place when we are in class together. Because this type of participation and contribution is predicated on your attendance, attendance is a critical part of your final grade. We have only ten class sessions together and there are no “make up” assignments for missed classes. Perfect attendance absent any substantive participation (see below) earns you a “C,” but possibly a lower grade if your attendance actually detracts from what is learned by the group as a whole. If you miss one session (10% of our classes) then you risk earning an “A/B” at best for participation. If you miss two sessions (means you will have missed 20% of our classes) then your final letter grade in the class can be no better than an “A/B.” I will of course revisit this criterion under exceptional circumstances. Additional missed sessions have a cumulative negative impact on your total final grade. Since strategy, unlike some of the functional classes you have taken, is a group-participant and highly interactive sport, it is helpful for you to think about your level of contribution in the class or in your groups using the following framework. This is how I calibrate your class contributions if asked, and the framework also captures my view about your individual and group written work: Outstanding contributor – A. In-class contributions reflect exceptional preparation. Ideas offered are always substantive, and provide one or more major insights as well as direction for the class. Arguments are well supported, persuasively presented, and reveal that this person is an excellent listener. Comments invariably help others to move their thinking to a higher plane. If this person were not a member of the class, the quality of our discussions would be greatly diminished. Good contributor – A/B. In-class contributions reflect thorough preparation. At a minimum, I expect and hope that all class members to fall into this category. Ideas offered are usually substantive, and provide good insights and sometimes direction for the class. Arguments are generally well supported and often persuasive, and reveal that this person is a good listener. Comments usually help others to improve their thinking. If this person were not a member of the class, the quality of our discussions would be diminished considerably. Adequate contributor – B. Contributions reflect satisfactory preparation. Ideas offered sometimes provide useful insights, but seldom offer a major new direction for discussion. Supporting arguments are moderately persuasive. Comments occasionally enhance the 7 Course: Global Strategic Management, Class XIII Web: http://instruction.bus.wisc.edu/mcarpenter/ Instructor: Mason A. Carpenter mcarpenter@bus.wisc.edu (608) 262-9449 learning of others, and indicate that this person is a passable listener. If this person were not a member of the class, the quality of our discussions would be diminished somewhat. Unsatisfactory contributor - C. Contributions in class reflect inadequate preparation. Ideas offered are seldom important, often irrelevant, and do not provide insights or a constructive direction for the class. Integrative comments and higher-order thinking are absent. This person does very little to further the thinking and potential contributions of others. Non-participant – C/D. The person has said little or nothing in this class to date and so has not contributed anything, bordering on detracting from the overall quality of the session. Such persons are free-riders because they have benefited from the thinking and courage of their peers but have offered little in return. If this person were not a member of the class, the quality of the discussion would be unchanged or possibly improved. Other Administrative Details Faculty have different expectations as to class behavior and course norms – here are mine. 1. I plan to be prepared for every class and I hope you will do the same. I frequently call on individuals whose hands are not raised. Please let me know before the start of the class if some emergency has made it impossible for you to be prepared adequately for that class. This avoids embarrassment for us both. 2. Given the importance of class participation, I will seek to learn your names as quickly as possible. To facilitate this I ask that you to use a name card at all times. 3. Please turn off cell phones and live web-access during our sessions together. These external distractions disrupt class and lower the quality of our discussions and interactions. In-class Webbrowsing affects your ability to participate, and so it will likely affect your final grade. 4. I will be happy to discuss the course, your progress, or any other issues of interest to you on an individual basis. Please see me in class or call to set up an appointment. My office number is 262-9449. You can call me at home before 9 p.m., 831-8327. E-mail is the surest way to track me down – mcarpenter@bus.wisc.edu, and I will typically respond within 48 hours. 5. Across and within group work is acceptable and encouraged for purposes of general case preparation. However, the final product of individual and group written assignments must be solely that individual or group’s own work. The consequences of violating this honor code are severe. The university deals very harshly with academic dishonesty by students, even a first-time offense. 6. Unless stated otherwise, written work is due no later than the beginning of the class session during which the case will be discussed (or as otherwise assigned). Since I’m looking for your best efforts, please do not ask me to preview your assignment prior to handing it in. 8 Course: Global Strategic Management, Class XIII Web: http://instruction.bus.wisc.edu/mcarpenter/ Instructor: Mason A. Carpenter mcarpenter@bus.wisc.edu (608) 262-9449 Overarching Frameworks Two specific frameworks will be employed in this course to describe strategy formulation and implementation in the face of change, and amplify the interdependence of formulation and implementation. Each of these frameworks is covered in your readings, and you will be expected to apply them regularly in your class and written work.. For instance, your group assignment for the second session requires that you apply the models shown in Figures 1 and 2 below. 9 Course: Global Strategic Management, Class XIII Web: http://instruction.bus.wisc.edu/mcarpenter/ Instructor: Mason A. Carpenter mcarpenter@bus.wisc.edu (608) 262-9449 Figure 1: The Strategy Diamond Arenas -- where will we be active? (and with how much emphasis?) Arenas Which product categories? Which market segments? Which channels Which geographic areas? Which core technologies? Which value-creation strategies? Staging -- what will be our speed and sequence of moves? Speed of expansion? Sequence of initiatives? Staging Pacing of initiatives? Timing of implementation lever changes and strategic leadership intervention Economic Logic Vehicles Vehicles -- how will we get there? Internal development? Joint ventures? Licensing/franchising? Alliances? Acquisitions? Differentiators Economic Logic -- how will returns be obtained? Lowest costs through scale advantages? Lowest costs through scope and replication advantages Premium prices due to unmatchable service? Premium prices due to proprietary product features? Differentiators – how will we win? Image? Customization? Price? Styling? Product reliability? Speed to market? 10 -11- Figure 2: Strategy Implementation Implementation Levers: INTENDED Organizational structure STRATEGY Systems and processes REALIZED & EMERGENT STRATEGIES People and rewards Strategic Leadership: Lever & resource allocation decisions Selling the strategy to stakeholders 11 -12Spring 2006 -- Detailed Course Calendar & Assignments Week 1* Session 1: January 12 Case: Amgen, Inc.: Planning the Unplannable (HBS 9-492-052) Readings: Syllabus Text chapters 1-4, and skim 11. We will use this first session’s readings and case to frame our future sessions and the questions pertinent to global strategic management. By the early 1990s, Amgen--a pharmaceutical company started little over a decade before as Applied Molecular Genetics--was within range of becoming a billion-dollar company. With two extremely successful biotechnology drugs on the market, Amgen stood as the largest and most powerful independent company of its type in the world. Top executives in the company viewed long-range planning as an important ingredient in the firm's success; many others--including some of the firm's scientists--were less sure. With Amgen's sales expected to continue to grow rapidly, the firm's long-range planning process would be put to the test. Our first case shows the different, sometimes paradoxical perspectives held within a single, dynamically changing company toward the issue of long-range planning. You are challenged to synthesize these views into a coherent picture of a firm's growth amid great uncertainty. Strategic planning is a pretty common-sense process. The first step is typically analysis (internal and external), and the second step is strategy development, which starts with a vision. Then you execute in step 3, which provides feedback into Step 1 again. Class Preparation: 1. Use the five diamond and implementation models (Exhibits 1.4 and 1.6 in your text) to summarize Amgen’s situation. 2. What are the firm’s key success factors (term is defined in Chapter 4). What are some of the contingencies that Amgen has to plan for? 3. What roles does the strategic planning process play at Amgen? How useful is it? 4. Summarize what changes, if any, you would recommend to make the strategic planning process at Amgen more effective. Team #1 Assignment: Please prepare a PowerPoint slide summarizing your key recommendations (in response to question #4). 12 -13Session 2: January 13 Case: Jeff Immelt at GE Readings: Text chapters 1-4, and skim 11 after reading the GE case to help craft your answer to the case questions. This case follows the actions of GE CEO, Jeff Immelt, as he implements a growth strategy for the $150 billion company in a tough business environment. In four years, he reinvigorates GE's technology, expands its services, develops a commercial focus, pushes developing countries, and backs "unstoppable trends" to realign GE's business portfolio around growth platforms. At the same time, he reorganizes the company, promotes "growth leaders" into top roles, and reorients the culture around innovation and risk taking. Finally, in 2006, he sees signs of growth, but wonders whether it is sustainable. After reading the case, ask yourself whether Immelt has put all the pieces into place to support his vision and new strategy – what pieces are missing? Preparation Questions: 1. How difficult was the task facing Immelt assuming the CEO role in 2001? What imperatives are there for change? What incentives are in place to maintain the past? 2. How different is his approach to taking charge from Jack Welch’s first few years after becoming CEO in 1981? How similar is the task each man faced? 3. What do you think of the broad objectives Immelt has set for GE? Can a giant global conglomerate hope to outperform the overall market growth? Can size and diversity be made an asset rather than a liability? 4. What is your evaluation of the growth strategy Immelt has articulated? Is he betting on the right things to drive growth? 5. After 4 ½ years, is Immelt succeeding at his objectives? How well is he implementing his strategy? What are his greatest achievements? What is most worrying you? 6. What advice would you offer to Immelt as he faces the next stage of leadership of GE? What should his calendar look like the next 90 days? All Teams Assignment: (Hand in at start of class. No more than three pages, name on first page, single spaced type, Times New Roman 12-point font). Answer question 6 in the form of a memo coming from Jeff’s trusted advisor. Be sure to provide a broad vision, as well as the 90-day action plan. Team #2 Assignment: Prepare up to five PowerPoint slides walking the class through your response to the all-teams assignment. 13 -14Week 2* Session 3: January 26 Case: IBP and the U.S. Meat Industry (HBS 9-391-006) Readings: Text Chapters 5 & 6 (and skim 7) The IBP case contains more than enough material for a lengthy discussion about the appropriate strategy and scope of the firm. It provides you with an opportunity to apply the value chain, concepts from the resource-based theory of the firm, and Porter's five forces analysis, and industry disruption. Through this case you will come to understand the basic concepts of industry attractiveness and generic business-level strategy, and eventually to fully understand IBP's competitive position. You will then move on to grapple with the definition and benefits of broad scope in the U.S. Meat Industry. Finally, this case allows us to recommend a strategy that is built on the acquisition of new resources or distinctive competencies. Your ultimate objective will be to articulate how IBP can build those resources. Preparation Questions: 1. What has been IBP’s strategy, and what strategic issues does IBP face in 1990? 2. What do the internal and external perspectives (Chapters 3 and 4) help you to say about IBP’s situation? What do they not explain? 3. What alternatives should IBP be considering? Why are these the best alternatives? 4. What should IBP do? What weaknesses must it overcome to achieve this? All Teams Assignment: (Hand it at start of class. No more than four pages, names on first page, single spaced type, Times New Roman 12-point font). Based on your work with questions 1-4, develop a business case for what IBP should do. Refer to the final project directions for the essential points such a business case should develop or make. Team #3 Assignment: Prepare up to five PowerPoint slides walking the class through your response to the all-teams assignment. 14 -15Session 4: January 27 Case: Copeland Corporation/Bain & Company Readings: Text Chapters 5 & 6 (and skim 7) The Copeland Corporation/Bain & Company video case address the renewal and sustainability of competitive advantage. We will emphasize that any such advantage is likely to be sustained only if management recognizes its bases, and works consciously to defend them. We will come to understand the critical features of sustainable advantages, discuss the contestability of such advantages, the effect of historical resource allocation decisions on subsequent choices, and solutions to management myopia. Importantly too, this case shows us the inner workings behind the competitive dynamics we see at the market and industry level. Unlike the other cases we will study, Copeland/Bain is not a traditional written case "story." In a video we will view together in class, Bain & Co.'s 1989 consulting engagement for Copeland is profiled. Copeland is a division of Emerson Electric that manufactures compressors for air conditioning systems. In this video case, Copeland is considering making the largest capital investment in its history in a new technology, the scroll compressor. Before going to the Emerson Electric Board for final approval, they have hired Bain & Co., a management consulting firm, to assess whether Bain believes that it is prudent to make such an investment. You are asked to play the role of the consultants, and to design a process for answering what they view as the key strategic questions raised. Prior to class, review the written material provided on Copeland/Bain and use it to develop a preliminary response to the preparation questions. Preparation Questions: 1. What are the specific strategic issues facing Copeland management as they prepare to make a capacity decision for the scroll compressor? What does it tell you about Copeland's "strategic intent?" (i.e., its long term objectives in terms of what it wants the rules of competition to look like). 2. What analytic techniques might you use to structure your thinking about the issues? 3. What questions remain to be answered? 4. What hypotheses can you develop concerning the answers to those questions? 5. What data do you need to test those hypotheses? How will you obtain it? 6. What should we be listening for during our interviews with the Copeland executives? Team #4: Two slides. Walk us through a PowerPoint slide of your five, highest yield questions or listening points for the Copeland executives. On your second slide, outline your team’s “listening” strategy (i.e., roles, etc.). 15 -16- Week 3* Session 5: February 9 Case: Millennium Pharmaceuticals (A) (HBS 9-600-038) Readings: Chapters 8 & 9 Millennium Pharmaceuticals, a leading biotechnology firm, has pharmaceutical and technology alliances with large firms, including Bayer AG, Monsanto, and Eli Lilly & Company. Central to its strategy and success in forming alliances is a technology platform for experimentation in drug discovery, considered to be one of the finest in the industry. At the same time, Millennium is using the technology platform to fundamentally rethink how it can discover new drugs and eventually become an integrated pharmaceutical company. This dual strategy – developing and selling its technology platform through alliances and leveraging these alliances to build downstream drug development capabilities – is being challenged in August 1999, when the European agribusiness conglomerate Lundberg is proposing a technology alliance to Millennium’s senior management. Preparations Questions: 1. How has the biotechnology industry changed over the last few years? 2. How has Millennium competed since it was founded in 1993? How has it managed its rapid growth? 3. Using the five-diamond framework, how would you characterize Millennium 's strategy? How would you describe the way Millennium brings together technology, strategy, organization, and culture? 4. What has been Millennium's alliance strategy? How has it differed from other biotechnology firms? How and why is M able to do this? 5. As CEO Marc Levin, would you pursue the Lundberg alliance? Why or why not? Other than Team 5, come to class prepared to identify the terms under which you would find such an alliance acceptable. Team 5: Prepare a five-slide PowerPoint presentation that summarizes your case for the Lundberg alliance. 16 -17Session 6: February 10 Case: Wendy Simpson in China (not in binder, this is a “live” case) Readings: Chapters 8 & 9, Alliances in China (from Website) This multi-faceted, interactive two-part case covers a number of important issues associated with doing business in China. It provides the opportunity to explore challenges on three different levels: Country: What should China’s role be in an organization’s global value chain? Organization/industry: How to grow a Chinese company--an almost 50:50 joint venture (JV)--on the global stage to benefit both the Chinese and Western parents by blending the best from the two sides? Personal: As a middle-management expatriate employed by the Western parent, how to build bridges between the Western and Chinese sides? The story is told by the Western parent, a European-based hi-tech global leader operating for more than a century. It had been operating in China since the early 1980s, primarily through a very successful joint venture (JV) in which it held a minority interest, as required by Chinese law. To protect its intellectual property, the company limited its exposure in China to one product through this JV. The Chinese partner was a stateowned enterprise (SOE) and had the strongest national sales and distribution presence for selling the product in the China market. Although the product technology was well known in China, it was aging. In the early days, the market was orderly. All profits had historically been retained in the business. The company essentially neglected the JV. However, in the late 1990s, because the industry worldwide was suffering while the China market was booming, the JV found itself at a crossroads: Both partners were wondering whether this JV was the best vehicle to bring newer technologies to China and enhance long-term profitability. In 1997 Wendy Simpson joined the company as Senior Vice President – Sales, Marketing and Communications for the Asia Pacific region. With a small team, she presented several strategic scenarios to the top management. The company approved the option of going into the JV stronger. After much negotiation, the Chinese government agreed to form a new JV, with a Chinese identity, with the company. When dealing with the governance and operational issues of the new Chinese company, Simpson faced challenges arising from the cultural differences between the two sides, and the gap between the mindsets and behaviors developed in the Chinese SOE environment and those developed in international businesses. Therefore, during this period, Simpson’s role had expanded from being more traditional to a coaching and bridging one. And because she was in the field and witnessed the rapid changes in China’s competitive landscape and the emerging strength of manufacturing and innovation there, she also recommended to corporate headquarters that China should take on the fabrication/assembly and R&D activities of the company. This case raises several issues regarding: How to handle various governance and operational issues when growing a joint venture that is almost equally owned by a Chinese SOE and an international company listed on the stock market? What should China’s role be in an organization’s global value chain? How do you influence a large, bureaucratic, mature organization when you are not at the very top and far away from the corporate headquarters? How do you build bridges between the Chinese and Western sides? 17 -18Week 4* Session 7: February 23 Cases: Masco (A) & Household Furnishings Industry Readings: Chapters 7 & 10 This session concludes our explicit focus on industry with a discussion of industry restructuring and serves to bridge competitive strategy and corporate strategy by considering a specific decision to enter a new industry -- one that, due to its very low average profit margins, most analysts would describe as undesirable. To facilitate this discussion, we are going to look at the question of whether Masco should enter the household furnishings industry, and if so should it do so through acquisition. Masco provides a good example of a firm that has successfully followed a constrained diversification strategy. Influencing Masco’s decision will be the changing conditions in the furniture industry, along with an understanding of what resources would give Masco a distinct competitive advantage. This is a very rich case because you are provided with detailed background on the furniture industry itself, along with a detailed description of Masco, its historical metalworking businesses, and its initial efforts at diversification. Specifically, this case provides you an opportunity to (a) apply Porter's Five Forces Analysis to the furniture industry; (b) identify leverage points that would lead to profitable industry restructuring; (c) determine if Masco is the firm to take on that job; and (d) identify what its entry strategy should be. Preparation Questions: 1. How can we explain Masco’s success to date? 2. Is the furniture industry attractive for anyone to enter? In your teams, diagram a five-forces+1 analysis of this industry as part of your team assignment below. 3. Should Masco enter the furniture industry? 4. What myths and reality is Masco likely to face? 5. What is the best entry strategy? 6. How well does this entry strategy position Masco for the long term? All Teams Assignment: Assume that Masco enters the furniture industry and outline an entry strategy for Masco. Why does your strategy position it best for the long term? Be convincing and specific in terms of segments and acquisition targets (or de novo approach); hand in your group's three-page summary (including the industry analysis diagram) at the start of class. Team 6: In five PowerPoint slides or less, use the strategy diamond to map out your Masco entry strategy and how this strategy and sequence of actions positions Masco for long-term advantage. Why would your investment bankers buy into this deal? 18 -19Session 8: February 24 ***Turn in network survey (see end of syllabus)*** Cases: CISCO Systems. Acquisition integration for manufacturing (A) (HBS 9-600-015) Grand Junction (HBS SB186) Reading: Chapters 7 & 10 While Cisco Systems is not the high-flyer it once was, it acquisition integration approach is still heralded as one of the most sophisticated and successful. We will use this pair of cases to study this approach as well as look at the acquisition through the eyes of a potential target. Grand Junction lets us explore the entrepreneur’s dream of often developing a company to a point where one either takes it public or sells the firm to another company. This second case gives us the opportunity to explore these questions in a high tech start-up. Cisco Systems Inc 1. What is Cisco acquiring when it buys a company in general? What would it be buying with Summa Four in particular? 2. Under what conditions does this appear to be an appropriate approach to acquisitions? Under what conditions might it not be desirable? What aspects of Cisco’s the acquisition integration strategy would appear to apply to all acquisitions? All Teams Assignment: Use two pages to summarize a specific acquisition integration plan for Summa Four that addresses Keller’s concerns and is consistent with Cisco’s acquisition approach. Be specific. Hand this in at the start of class – two groups will be chosen at random to walk the class through their acquisition integration strategy. Grand Junction 1. Given the representations that Charney and other senior managers had made to everal newly hired key employees, should they meet with these people to explain their consideration of the Cisco offer before making a decision? If Grand Junction decides to be acquired, how should Charney and his management team inform their employees? 2. What do you think of Charney’s final offer? Is it a fair valuation for Grand Junction? Explain your reasoning. 3. From the perspective of the senior management and Board of Cisco Systems, evaluate the final offer. Should Cisco accept this offer? Why? 4. Should Grand Junction go public or be acquired? Why? Evaluate the issue from the perspective of each of the stakeholders in Grand Junction. Who are the relevant stakeholders? 19 -20Week 5* Session 9: March 9 Cross cultural simulation Readings: Skim Negotiating with the Romans (A) & (B) (On our web site) Session 10: March 10 Cases: Dennis Hightower (HBS9-395-055 & 9-395-056) Readings: Text – Chapter 12 (and re-skim Chapter 8 after case #1) This case puts you in the shoes of Dennis Hightower, a Disney manager. As the case states, you are given the mandate to "Go out and grow the business. Do something different from what has been done in the past. Develop a strategy and bring it back to us in three months." Follow the directions accompanying the case and be prepared to dissect Hightower's actions. One quarter of all managers transition to a new role or job each year. An upwardly mobile manager can expect to face a transition every 2 1/2 to 3 years. A typical transition in a large organization affects 12.4 people, and it takes an average of 6.4 months for a new leader to move through his or her "transition deficit" to become a positive contributor in the new role. Too few managers--and organizations--approach these transitions with a strategic plan. First, please read the "Taking Charge" case. Based on this case, prepare answers to the following questions: 1. 2. What challenges does Dennis Hightower face in his new position? Sketch out a detailed plan of action for Dennis Hightower to pursue over the next 3 months. Next, AFTER HAVING WRITTEN OUT YOUR ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS 1 & 2 ABOVE, please review Chapter 8 on global strategy and the Transnational Manager case. After studying the reading and case, be prepared to discuss the following questions in class: 1. 2. 3. 4. Evaluate the pacing and sequencing of Hightower's actions from 1988 to 1994. How would you evaluate Hightower's approach to bringing about change in his organization. Compare his approach to other approaches you may be familiar with. What should Hightower do about the apparel business? Learning from Hightower's experiences, what do you think are some of the challenges of building a transnational (global) organization? All Team Assignment: Draft out a detailed three-month action plan (literally, a PDA calendar) for Hightower and summarize it in two pages or less. Hand it in at the beginning of class. Be specific about how this strategy is good for Hightower and good for Disney. 20 -21EMBA Global Strategy Class Participation Self-Assessment NAME: ____________________________ Please take a few moments to reflect on both your own participation and that of others in the class (turn this in to me or Connie at the end of our last class session). 1. Review the criteria for class participation in the syllabus. Assess your own participation, indicating the # of classes missed and the value of your contribution by indicating the grade you think you feel you deserve for class participation (taking into account both the quantity and the quality of your contribution to our discussions). Number of classes missed: ______________ Participation Grade you think you deserved: _______________ (A, A/B, B, C, etc.) 2. Please identify up to 6 of your classmates that you feel significantly contributed to the class discussions as a result of their thorough analysis or by adding insights or moving the discussion in a meaningful direction. ______________________________ _____________________________ ______________________________ _____________________________ ______________________________ _____________________________ 3. Allocate 100 points based on the contribution of you and your group members on the final project (strategic audit). Points yourself _________ __________________________________ _________ __________________________________ _________ __________________________________ _________ __________________________________ _________ __________________________________ _________ __________________________________ _________ 100 Points 21 -22APPENDIX: WHY WE USE THE CASE METHOD IN STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT The case method is one of the most effective means of management education. It is widely used in schools of business throughout the world, and this use is predicated upon the belief that tackling real business problems is the best way to develop practitioners. Real problems are messy, complex, and very interesting. Unlike other pedagogical techniques, many of which make you the recipient of large amounts of information but do not require its use, the case method requires you to be an active participant in the closest thing to the real situation. It is a way of gaining a great deal of experience without spending a lot of time. It is also a way to learn a great deal about how certain businesses operate, and how managers manage. There are few programmable, textbook solutions to the kinds of problems faced by real general managers. When a problem becomes programmable, the general manager gives it to someone else to solve on a repeated basis using the guidelines he or she has set down. Thus the case situations that you will face will require the use of analytical tools and the application of your personal judgment. Sources of Cases All the cases in this course are about real companies. You will recognize many of the names of the companies although some of them may be new to you. These cases were developed in several different ways. Occasionally, a company will come to a business school professor and request that a case be written on that company. In other situations, a professor will seek out a company because he or she knows that the company is in an interesting or difficult situation. Often, the company will agree to allow a case to be written. Occasionally, cases will be written solely from public sources. This is perhaps the most difficult type of case writing because of the lack of primary data sources. In those situations where a company has agreed to have a case written, the company must “release” the case. This means that they have final approval of the content of a given case. The company and the case writer are thus protected from any possibility of releasing data that might be competitively or personally sensitive. Public source cases, obviously, do not need a release. Given the requirement for release, however, it is amazing the amount of information that companies will allow to be placed in a case. Many companies do this because of their belief in the effectiveness of the case method. Preparing for Class When you prepare for class, it is recommended that you plan on reading the case at least three times. The first reading should be a quick run-through of the text in the case. It should give you a feeling for what the case is about and the types of data that are contained in the case. For example, you will want to differentiate between facts and opinions that may be expressed. In every industry, there is a certain amount of “conventional wisdom” that may or may not reflect the truth. On your second reading you should read in more depth. Many people like to underline or otherwise mark up their cases to pick out important points that they know will be needed later. Your major effort on a second reading should be to understand the business and the situation. You should ask yourself questions like: (1) Why has this company survived? (2) How does this business work? (3) What are the economics of this business? On your second reading, you should carefully examine the exhibits in the case. It is generally true that the case writer has put the exhibit there for a purpose. It contains some information that will be useful to you in analyzing the situation. Ask yourself what the information is when you study each exhibit. You will often find that you will need to apply some analytical 22 -23technique (for example, ratio analysis, growth rate analysis, etc.) to the exhibit in order to benefit from the information in the raw data. On your third reading, you should have a good idea of the fundamentals of the case. Now you will be searching to understand the specific situation. You will want to get at the root causes of problems and gather data from the case that will allow you to make specific action recommendations. Before the third reading, you may want to review the assignment questions in the course description. It is during and after the third reading that you should be able to prepare your outlined answers to the assignment questions. There is only one secret to good case teaching and that is good preparation on the part of the participants. Since the course has been designed to “build” as it progresses, class attendance is also very important. Class Discussions In each class, I will ask one or several people to lead off the discussion. If you have prepared the case, and are capable of answering the assignment question, you should have no difficulty with this lead-off assignment. An effective lead-off can do a great deal to enhance a class discussion. It sets a tone for the class that allows that class to probe more deeply into the issues of the case. The instructor’s role in the class discussion is to help, through intensive questioning, to develop your ideas. This use of the Socratic method has proved to be an effective way to develop thinking capability in individuals. The instructor’s primary role is to manage the class process and to insure that the class achieves an understanding of the case situation. There is no single correct solution to any of these problems. There are, however, a lot of wrong solutions. Therefore, I will try to come up with a solution that will enable us to deal effectively with the problems presented in the case. After the individual lead-off presentation, the discussion will be opened to the remainder of the group. It is during this time that you will have an opportunity to present and develop your ideas about the way the situation should be handled. It will be important for you to relate your ideas to the case situation and to the ideas of others as they are presented in the class. The instructor’s role is to help you do this. The Use of Extra- or Post-Case Data You are encouraged to deal with the case as it is presented. You should put yourself in the position of the general manager involved in the situation and look at the situation through his or her eyes. Part of the unique job of being a general manager is that many of your problems are dilemmas. There is no way to come out a winner on all counts. Although additional data might be interesting or useful, the “Monday morning quarterback” syndrome is not an effective way to learn about strategic management. Therefore, you are strongly discouraged from acquiring or using extra- or post-case data. Some case method purists argue that a class should never be told what actually happened in a situation. Each person should leave the classroom situation with his or her plan for solving the problem, and none should be falsely legitimized. The outcome of a situation may not reflect what is, or is not, a good solution. You must remember that because a company did something different from your recommendations and was successful or unsuccessful, this is not an indication of the value of your approach. It is, however, interesting and occasionally useful to know what actually occurred. Therefore, whenever possible, I will tell you what happened to a company since the time of the case, but you should draw your own conclusions from that. 23 -24- Network Assessment Exercise: Executive Version Introduction This exercise is based on network instruments designed to help you identify patterns in your approach to developing networks of relationships. Your "network" refers to the set of relationships that help you advance professionally, get things done, and more generally, develop personally and professionally. Directions Follow the instructions for Steps 1 through 5 on the following pages. When you have completed the exercise, hand in Step 5 (page 6) and only Step 5. The information you turn in will be anonymous, so please DO NOT write your name on page 6. Please DO NOT turn to page 6 (Step 5) until you have completed pages 2 to 4 of this exercise. 24 -25- Step 1: List Your Network Contacts In answering the following questions, you may list people from ANY context. It is not necessary to limit yourself to individuals who work for your company. People with whom you have more than one kind of relationship can be listed more than once. In the blanks that follow each question, please list their names or initials. You may list as few or as many as you wish, or leave a question blank if no one comes to mind. 1. Discussing important work matters If you look back over the last two to three years, who are the people with whom you have discussed important work matters? This may have been for bouncing ideas for important projects, getting support or cooperation for your initiatives, evaluating opportunities or any other matters of importance to you. 2. Getting the job done What people have been most helpful and useful in accomplishing your job? Consider people who have provided leads, made introductions, offered advice in your decision making, or provided resources. 3. Advancing your career List those people who have contributed most significantly to your professional development and career advancement during the past two to three years. 25 -26- Step 2: Consolidate Your List Consolidate the names listed in Step 1 onto the Network Grid on page 4. No one person should be listed twice. Step 3: Describe the Closeness of the Relationship For each person listed on the network grid, indicate the closeness of your relationship with them by placing an "X" on a continuum from "very close" to "close" and "not very close," to "distant." Very close relationships are those characterized by high degrees of liking, trust, and mutual commitment. Distant relationships are those characterized by not knowing the person very well, or by having very little liking, trust, and mutual commitment (i.e., problematic relationships). For an example of how to complete this step, see the Sample Network Grid on page 5, entitled "Pat's Network." Step 4: Compute the Density of Your Network Density refers to the extent to which the people in your network know each other. Using the grid on the next page, indicate who knows who in your network by placing a checkmark in the cells corresponding to each acquainted pair. Leave a cell blank if the pair do not know each other, or if you do not know whether they know each other. Start with person 1, for example Lisa in the Sample Network Grid on page 5. Going across the grid, Lisa knows Jack (2), Jeff (3), and Samantha (8), but no one else in Pat's Network. Go on to person 2, Jack. Jack knows Rick (5), Linda (6), Samantha (8), and David (10). Go on to person 3, and so on. Once you have finished checkmarking who knows who, compute the density of YOUR network through the following steps: a) Total number of people in your network To follow our example, Pat's N = 10 b) Maximum Density (i.e., if everyone in your network knew each other). Pat's maximum density is (10*9) ÷ 2 = 45. c) d) N = ________ [N * (N - 1)] ÷ 2 = M M = ________ Total number of checkmarks on your network grid (i.e., the Number of relationships among people in your network). Pat's C = 19. C = ________ Density of Your Network. Pat's D = 19 ÷ 45 = .42 C÷M=D D = ________ When you have completed Steps 2, 3, and 4, go to page 6 and complete Step 5. 26 -27Network Grid Step 3: Relationship Very Close Close Not Very Close Step 2: List Names Distant Step 4: Density of Network 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. USE ONLY UPPER RIGHTHAND DIAGONAL TO COUNT AND CALCULATE YOUR NETWORK CHARACTERISTICS 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 27 -28SAMPLE Network Grid: Pat's Network Step 3: Relationship Very Close Close Not Very Close Step 2: List Names Distant Step 4: Density of Network 2 X 1.Lisa X 2.Jack X 3.Jeff 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 4.Noah X 5.Rick X 6.Linda X X 7.Jay 8.Samantha X 9.Stacy X X 10.David 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. USE ONLY UPPER RIGHTHAND DIAGONAL TO COUNT AND CALCULATE YOUR NETWORK CHARACTERISTICS 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 28 -29- Step 5: Summarize the Network Information Complete the sections below, make a photocopy, and hand in this page and only this page. To maintain anonymity, please DO NOT write your name on this sheet. Individual Information (circle applicable) Gender Male Female Race/Ethnicity White African or African-American Asian or Asian-American Hispanic Other ______ Nationality (by region) U.S. and Canada Latin America (Mexico, South, and Central America) Europe Africa and the Middle East Asia Australia and New Zealand Tenure Years in this industry ______ Years with this employer ______ Years in present position ______ Network Information 1. Total number of people listed on the Network Grid (from Step 2) _____ 2. Number of "Very Close" relationships listed on the Network Grid (from Step 3) _____ 3. Density of your network (D from Step 4) _____ (needs to be less than or equal to 1) 4. Look over your Network Grid and determine the number of people who are: a) b) c) Your senior (higher up in your or another organization) Your peer (at your level in your or another organization) Your junior (below you in your or another organization) _____ _____ _____ d) e) f) From a different functional or product area From a different business unit, division, or office in your firm From a different firm _____ _____ _____ g) h) i) The same gender as you are Members of the same racial or ethnic group as you are The same nationality as you are _____ _____ _____ Keep a photocopy of this page so that you can refer to it later. 29 -30- Step 5: Summarize the Network Information Complete the sections below, make a photocopy, and hand in this page and only this page. To maintain anonymity, please DO NOT write your name on this sheet. Individual Information (circle applicable) Gender Male Female Race/Ethnicity White African or African-American Asian or Asian-American Hispanic Other ______ Nationality (by region) U.S. and Canada Latin America (Mexico, South, and Central America) Europe Africa and the Middle East Asia Australia and New Zealand Tenure Years in this industry ______ Years with this employer ______ Years in present position ______ Network Information 1. Total number of people listed on the Network Grid (from Step 2) _____ 2. Number of "Very Close" relationships listed on the Network Grid (from Step 3) _____ 3. Density of your network (D from Step 4) _____ (needs to be less than or equal to 1) 4. Look over your Network Grid and determine the number of people who are: a) b) c) Your senior (higher up in your or another organization) Your peer (at your level in your or another organization) Your junior (below you in your or another organization) _____ _____ _____ d) e) f) From a different functional or product area From a different business unit, division, or office in your firm From a different firm _____ _____ _____ g) h) i) The same gender as you are Members of the same racial or ethnic group as you are The same nationality as you are _____ _____ _____ Keep a photocopy of this page so that you can refer to it later. 30