Water quality and physical features of goliath grouper nursery

advertisement

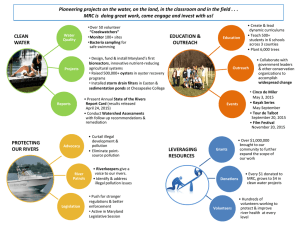

Water quality and physical features of goliath grouper nursery habitat in the Ten Thousand Islands Anne-Marie Eklund, Steve Wong, Jennifer Schull NOAA-Fisheries, Southeast Fisheries Science Center, Miami, Florida Matt Finn Huckleberry Fisheries, Goodland, Florida Chris Koenig and Felicia Coleman Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida The objectives of this project were to characterize the essential habitat for juvenile goliath grouper in their historical center of abundance, the Ten Thousand Islands of southwest Florida. All harvest of goliath grouper has been prohibited in U.S. waters since 1990, and the species is a candidate for the U.S. Endangered and Threatened Species List. We compared the abundance of juvenile goliath grouper from 1999-2000 in natural tidal passes, or rivers, to their abundance in channelized canals (Figure 1). These rivers and canals link the upstream freshwater system of the Big Cypress Basin to the system of bays that empty into the Gulf of Mexico through a series of channels around mangrove islands. Most of the area is completely undeveloped and protected, yet it is downstream from areas in the Big Cypress Basin that have been subjected to massive changes in water delivery over the years. This area will be affected by the activities of the Southern Golden Gates Estates restoration project (SGGE). The natural rivers should provide optimal microhabitat for the juvenile goliath grouper, including mangrove overhangs along eroded shorelines and rocky depressions in tidal passes. Canals, on the other hand, tend to have straightened shorelines with little to no eroded banks and mangrove overhangs. Since they are dredged, canals are also of relatively uniform bathymetry, lacking the natural depressions that rivers contain. We hypothesized that the physical features of the two habitat types would differ and that the goliath grouper would be more abundant in the natural rivers. In each river/canal, we used 40 crab traps and 10 fish traps, with each trap placed 0.05 nautical miles (nmi) apart. Beginning in 2000, we deployed YSI datasondes to continuously measure temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen and depth during the time that the traps were soaking. The amount of eroded (vs. depositional or straight) shoreline was measured by taking GPS waypoints at the beginning and end of each section of eroded shoreline and measuring the distance between the two points using GIS ArcView software. The heterogeneity of the bottom (i.e. the presence/absence of rocky holes and other obstructions) was estimated by taking a depth reading every 0.1 nmi along each side of the river/canal. The change in depth from each reading was then calculated and averaged for the entire river/canal. A total of 687 juvenile goliath grouper were caught in the nine rivers and canals that were sampled from 1999-2000. There was a lot of variability of catch among the rivers, making comparisons of rivers and canals more difficult that we had initially thought. Goliath grouper CPUE and total catch were highest in Little Wood River, Palm River, and Blackwater River. Very few goliath grouper were caught in the Wood, Pumpkin and Whitney Rivers, however, due to anoxic conditions in these rivers. While two of the canals, Faka Union and 92 West Canal, had lower CPUE and total catch of goliath grouper than in several rivers, 92 East Canal had higher CPUE and total catch than many of the natural rivers. Our hypothesis that natural rivers would provide better and more habitat than canals would for juvenile goliath grouper was based on the assumption that the shorelines and bathymetry would be vastly different between rivers and canals. Rocky holes and mangrove undercuts should provide optimal habitat for goliath grouper in the form of shelter from current and an ideal location for ambush predator activities. Our visual assessment of Faka Union Canal bore out that hypothesis, since the canal is completely straight with no eroded shorelines and a uniform bathymetry. The two other canals, however, are not completely straight and the slight meanders have resulted in some shoreline erosion, providing undercut habitat for goliath grouper and other fish. In fact, the 92 East Canal had more eroded shoreline than all of the natural rivers, except the Little Wood River. However, none of the canals had heterogeneous bathymetry, as expected. Optimal conditions for juvenile goliath grouper appear to be a combination of the presence of eroded shorelines and depressions along the bottom, high tidal amplitude and tidal currents, salinity variation within an acceptable range (so that the area does not become totally fresh or hypersaline) and no extended periods of anoxia. The Little Wood and Palm Rivers had the best combination of all of these features, and consequently yielded consistently higher numbers of goliath grouper. What may be more important to determine, however, is why some of the rivers in the Ten Thousand Islands provide more of the optimal habitat and conditions than the other rivers, particularly since the rivers are adjacent to one another and are all downstream from the same Big Cypress Basin. The SGGE may have direct impacts on the habitat of juvenile goliath grouper in the Ten Thousand Islands. Precious little is known concerning the animals in the natural rivers and canals in the area, with the bulk of the research activities taking place in upland and freshwater areas. However, the restoration activities will surely affect areas downstream. The Wood River, for instance, may be starved of upstream water flow, due to the presence of the Faka Union Canal. The SGGE project includes plugging the vast network of canals that lead to Faka Union in order to restore a more natural sheet flow. Undoubtedly, the Faka Union Canal and the adjacent riverine systems will be altered by these changes. The Whitney River has enough eroded shoreline and bathymetric complexity to be considered a river with optimal physical habitat for goliath grouper. The lack of water flow and periods of anoxia, however, led to high mortality of organisms found in our traps and a very low catch rate of fish. Should the sheet-flow be restored throughout much of Big Cypress Basin, areas like the Whitney River may be restored for goliath grouper and possibly other species of fish to have more optimal habitat in which to reside and grow. Figure 1. Six natural, tidally influenced rivers and three canals in the Ten Thousand Islands of southwest Florida, U.S.A. Canals on either side of U.S. Highway 92 are labeled 92 Canal West and 92 Canal East. The dots on the river and canal transects designate locations where fish traps and crab traps were placed to catch juvenile goliath grouper, Epinephelus itajara, from 1999-2000. Eklund, Anne-Marie, NOAA-Fisheries, Southeast Fisheries Science Center, 75 Virginia Beach Drive, Miami, Florida 33149, Phone: 305-361-4271, Fax: 305- 365-4102, anne.marie.eklund@noaa.gov.