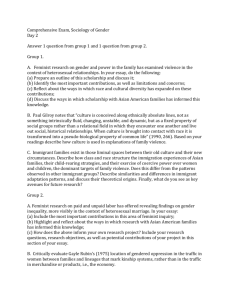

Feminist International Relations Kritik-MGW

advertisement