Microsoft Word - Yale University

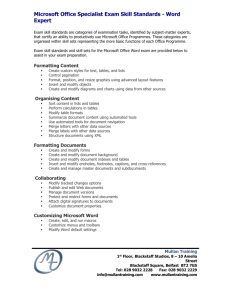

advertisement