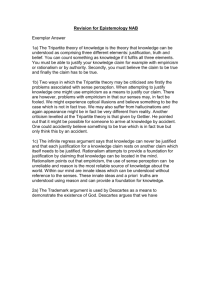

Epistemology Booklet

advertisement

Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy Epistemology By the end of this unit you will be able to Describe the tripartite theory of knowledge Describe the main problems associated with the tripartite theory Describe the key philosophical positions of rationalism, empiricism, coherentism and scepticism Describe Hume’s ideas on knowledge based on texts from An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (EHU) Explain and analyse Hume’s theories in EHU Quote relevant text from EHU to support your conclusions In part 1 of this unit we are going to focus on 3 questions that are vital in the area of Epistemology Why knowledge claims are a problem in Philosophy? What is knowledge? Can knowledge claims ever be truly justified? In part 2 of the unit we will look at David Hume’s theories regarding knowledge and in particular How do we acquire knowledge? Impressions and Ideas How do we decide on the different types of knowledge? Hume’s Fork Why knowledge claims based on past experiences are problematical – Causation and Induction Why knowledge claims are not specific to humans – Hume on the Reasoning of Animals 1 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy What is Epistemology? Epistemology comes from a Greek words episteme (“knowledge”) and logos (“word” or “theory”) and so can be thought of as the “theory of knowledge”. Epistemology is about how we get knowledge and how we can be sure that knowledge is reliable. Epistemology tries to separate true knowledge from opinion. Think about the following examples and decide which of the following is either true knowledge or statements of opinion. Give reasons for your choices. Santa exists Ben Nevis is the highest mountain in Scotland 7 x 2 is 14 Stella is the best lager in the world God exists Edinburgh is in Europe Teachers have absolutely no dress sense Blondes are stupid Parallel lines never meet School canteen food is really tasty A triangle has 3 sides A key point at this stage is that the main difference between knowledge and opinion is that knowledge would seem more certain than opinion – it would have some sort of evidence to support the claim. However, this can lead to problems as the proposition ‘Santa exists’ clearly suggests. Most children would be adamant the proposition is certain as they have it on good authority (parents/adults) and the evidence (presents) is real. So, although there seems to be good evidence that Santa does exist we all know (sorry if this comes as a shock) that Santa does not exist. Further, how do you know your parents are really your parents? How do you know you are not dreaming right now? How do you know things do not disappear when you are not looking at them? How do you know you even exist at all? For each of these questions, complete the certainty/uncertainty table below. 2 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy Proposition and certainty Proposition Evidence Santa Exists Parents/presents Are your parents really your parents? Are you dreaming right now? How do you know you even exist? Do things disappear when we don’t look at them? White people are superior to blacks Doubt Invented story In Epistemology, if there is any doubt at all about the knowledge claim then the knowledge becomes uncertain and cannot be claimed to be true. This becomes extremely important because when beliefs and laws are formed around uncertain knowledge claims then beliefs and laws based on flawed knowledge can be unjust and cruel (Jim Crow laws in USA and Apartheid in South Africa). Key question – what is epistemology? (k/u 5) 1) Why knowledge claims are a problem in Philosophy? As we have already seen, there is a real problem in establishing anything that could to be said to be certain. We could even argue that we cannot really know that 7 x 2 =14. So, does this mean that we can never really be certain of anything? 3 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy Appearance and Reality The first point to be made is that when philosophers talk about appearance and reality, they have very definite terms that apply to these distinctions. Appearance is how the world seems to be while reality is how it really is. But what does this mean? Film-makers constantly use this distinction and there have been hundreds of very successful films that draw out the differences between appearance and reality. The Matrix Trilogy is centred in a virtual computer created world where nothing is ‘real’. The same distinction is made in the ‘Truman Show’ where Truman’s whole life is situated in a world which is not ‘real’. In ‘The Island’, the same differences between what appears to be real and what is real emerge as the characters discover all they have ever believed to be true is false and they are nothing more than medical clones. These films help us to understand that knowledge can appear to be certain and beyond questioning but what happens to us if we discover our knowledge is false and has never been ‘real’? Some people can be happily married (or so they think) for years and then one of them discovers their partner has been having an affair! It could be argued that their lives only appeared to be happy but the reality of the situation was quite different. Some children are devastated if they discover they have been adopted and for some this leads to a questioning of everything they thought they ‘knew’. For many years people believed the Earth was flat and that the Earth was the centre of the Universe. Once these theories were shown to be false, knowledge increased and knowledge of the Earth changed from what appeared to be true to what was actually true – reality. So, a second point when looking at the difference between appearance and reality is that appearance is only temporal or temporary and it is very subjective because we rely on what we already seem to know. Reality on the other hand is not temporal it is eternal and objective (can be discovered). The belief that the Earth was flat was temporal and subjective as this was never the case 4 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy although it appeared to be true. The Earth has always been circular and therefore this truth has always been eternal and discoverable. This leads on to the third point surrounding appearance and reality – why does the distinction even exist? Some philosophers argue that if we base knowledge on our senses i.e. sight, sound, touch, taste and smell then we shouldn’t be surprised if this turns our to be false – even if our senses tell us it is true. Even if we use more than one of our senses to claim knowledge they can still fool us. If you hear a plane flying overhead we can know where it is by looking and listening. However, the plane tends to be much further ahead of our senses due to the speed of sound and the speed sound travels before we can hear it. If you look at the stars it is possible to see a star that has already exploded but because it is so far away the light of the explosion has not yet reached us – the star appears to be there but in reality it does not exist anymore! If you see a pencil in a glass of water it appears to be broken or an oar in the water appears to be bent! In all these cases, the knowledge we gain through the senses is not reliable – it only appears to be true! One of the first philosophers to highlight this problem was Plato. Discussion – do you think we live in a world where there is a difference between appearance and reality? Key Question – what is the difference between appearance and reality? (k/u4) 5 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy Plato Plato is one of the most famous Greek philosophers and he rejected the sceptic position (that knowledge can never be certain) and argued against the Sophists and their belief in cultural relativity. The Sophists were professional philosophers and lawyers who travelled around the Greek city states and taught people how to argue and debate and how to win public speaking contests at all costs. They usually demanded huge financial rewards for their services and it is fair to say Plato hated what they stood for. Sophistry (clever words that deceive in order to prove a point) sums up what Plato thought these people were about and if he were alive today he would probably see modern day sophists in many of our law courts! Sophists taught that there was no such thing as ‘absolute truth’ because the world was a constantly changing place in which people change their beliefs and values then it was impossible to establish any certain truth knowledge. To give examples of Sophist teaching, imagine you are living around 400BC in Athens; answer the following questions in your jotter. Give reasons for your answers. Is it right to own a slave? Should women be allowed to vote? Should homosexuality be banned? All of the above questions relate to the human condition and the freedoms associated with being human. However, human freedom can be entirely dependant upon answers to basic questions. If you answered ‘yes’ to the question on owning a slave then further questions can be asked – ‘should you physically punish a slave?’ or ‘can you rape a slave if you feel like it?’ If you answered no to owning a slave then who is going to do all the work? Why is slavery wrong? How are you going to become rich? The answers to these questions were different in different city states – in Athens slavery was allowed, women were not allowed to vote (they got half food rations and were not allowed to go out) and 6 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy homosexuality was frowned upon. In Sparta, perhaps the toughest place in Greece, slavery was frowned upon, women had a voice and homosexuality was encouraged – which of these societies were right? The Sophists argued there was no such thing as ‘right’ so ideals such as justice and rights were only arguments and the morality of the arguments was determined by those who could argue the best! Sophism teaches that morality is never fixed and societies choose rules and laws based around which speakers won the argument. This treats knowledge as being entirely subjective and temporal but is that the case? Is it true that slavery depends only on the culture that practices it? Equal rights for women depend on what people think? Persecution of homosexuals is allowed if people think it is alright to do so? Plato thought not, knowledge is eternal and objective, so in other words, slavery is always wrong, men and women are equal and sexual orientation based upon choice should never be punished. Plato hated sophistry and thought there were ‘absolutes’ and that these principles were constant and unchanging. Plato put forward his ideas in the Simile of the Cave in order to highlight the difference between appearance and reality. Plato thought that reality lay outside the cave and that those inside the cave only had an appearance or shadow of the real world. He also thought that those chained in the cave would not be convinced their world was only apparent regardless of the evidence. Sometimes philosophy becomes so abstract that it seems to lack any relevance to our everyday lives and the ideals of the Sophists seem lost in time. Look at the following examples and decide what you think should happen in each case. Two women try to get into a nightclub but are refused entry because the doormen think they are too drunk. The women get abusive with the door staff but are moved on. They are determined to get in and so walk around the building trying to find a back door. They come upon a line of open windows at the side of the building and climb in. One of the women climbed in through a window (it was the men’s toilet) and as she was jumping down hit her head on a sink. The other one landed badly on a wet floor and broke her ankle. They were quickly discovered and the police were called. 7 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy An elderly Florida woman had always wanted to own a big Winnebago motor home. When she retires from work she decides that she is going to buy one. She chooses the model she wants and arranges to pick it up. The salesman shows her how to operate the vehicle and explains all the equipment in it. The woman takes the Winnebago onto the freeway and heads home. Once she has reached the speed limit of 55 mph she sets the cruise control function and gets up from her drivers seat to make herself a cup of coffee. The Winnebago, worth around $250 000 crashes and is a complete wreck. A robber breaks into a house armed with a knife. The family are asleep but the robber (a heroin addict) disturbs them. The robber threatens the family with the knife. The father of the family attacks the robber with a poker and knocks him out. The father then calls the police. In all three of the above true stories we can see what Plato might describe as modern day Sophists in action. In the first example, the nightclub is sued by the women and they win their case. The nightclub is found guilty because it hasn’t ensured the safety of the women particularly because there were no ‘wet floor’ warning signs. Both women are awarded compensation amounting to £3 000. The woman sues Winnebago and is successful because the salesman did not properly explain that cruise control only affected the accelerator pedal and not the brakes or the steering. She gets a replacement motor home and compensation for trauma. Winnebago have to retrain all staff. Finally, the robber sues the homeowner and wins the case as the court decides ‘excessive force’ was used. The homeowner is ordered to pay the robber £750 in compensation and gets a suspended jail sentence. 8 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy In all three of these cases, lawyers used clever arguments based on health and safety and, for most people, made a mockery out of what is right and what is wrong. It was exactly for these reasons that Plato fought against the Sophists as he wanted to show that there must be standards of justice that do not change, that are timeless and real. Plato called these changeless truths ‘forms’ i.e. there are things in the world that are merely ‘forms’ of the perfect or original thing. Think about all the breeds of dog there are in the world! Even if we narrow that down to just terriers there are still many different ‘forms’ or types of terrier: West Highland, Scottish, Yorkshire etc. All of these forms of terrier have been bred for specific purposes but they all descend from one specific ‘form’ of terrier. The terrier is also a ‘form’ of a dog and so all dogs must be a ‘form’ of the original dog – none of which can be seen in the world today. If this applies to dogs then it can also apply to things such as beauty or justice and so Plato thought there must be an ideal ‘form’ for each of these things. Plato believed it was possible to know the ‘forms’ through logical reason and study and that once we discovered the true forms we would live in a world of reality and not merely appearance. Discussion – is it possible Plato was right about appearance and reality, reincarnation and the forms? Key questions – who were the Sophists and what did they do? (k/u 1) 2) Why did Plato hate the Sophists? (k/u 2) 3) What did Plato mean by the term ‘form’? (k/u 2) 4) Why did Plato believe the forms were important? (a/e 2) 9 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy 2) What is knowledge? When philosophers talk about knowledge or what it is to ‘know’ something, they are very clear that the word ‘know’ can have different uses. I can say that I know that Battle of Bannockburn was in 1314, that I know how to play the guitar or that I know the Algarve region of Portugal. In each of these examples knowledge is being claimed but the type of knowledge is different. Knowing that is propositional knowledge and can be factual or theoretical Knowing how is a skill or ability I know is knowledge through acquaintance of a place/person or thing Look at the table below and copy and complete in your jotter What is knowledge Statement I know that the Battle of Bannockburn took place in 1314 I know how to play the guitar I know the Algarve region of Portugal Type of knowledge Propositional knowledge Ability/skill knowledge Knowledge through acquaintance I know that the square root of 81 is 9 I know Alice I know that Alice fancies me I know how to wind Alice up I know that Scotland will not qualify for the next major competition I know that Gordon Brown was Prime Minister I know illegal drugs are harmful I know this exercise is a waste of my time In all of the above it is fairly clear which type of knowledge is being claimed. However, what happens if we drop the ‘that’ from the above statements? In most cases the distinctions remain fairly clear: I know the Battle of Bannockburn took place in 1314 is still clearly 10 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy propositional knowledge as this knowledge is not a skill and because we cannot claim to have been there neither is it knowledge through acquaintance. However, if we look at the last 2 examples the distinctions become less clear as ‘I know illegal drugs are harmful’ could be either propositional knowledge or knowledge through acquaintance. The same could be argued for the final statement. This has led to some philosophers claiming that there are no real distinctions as all 3 are types of knowledge and so all three are ‘knowing’. Key Questions 1) What are the 3 definitions of the word ‘know? (k/u3) 2) What are the differences between each of these definitions? (k/u3) 3) Give an example of each of the 3 definitions of ‘knowing’. (k/u3) 4) Why might some argue all 3 definitions are the same? (a/e2) The Tripartite Theory of Knowledge Whether you accept there is a genuine division in the 3 types of ‘knowing’ they are still important as analytic tools in deciding on validity and soundness. Plato, as we have already seen, did believe it was possible to have knowledge that was certain. Plato argued that for a proposition to be accepted as certain then it must fulfil 3 criteria We must believe the proposition We need to have supporting evidence to back up the belief It needs to be true These 3 strands are known as the Tripartite Theory of Knowledge or justified, true, belief. The 1st point is that the claim must be true – it must relate to reality rather than appearance. We cannot ‘know’ something that is false i.e. we cannot claim that the Earth is flat because this is simply false. 11 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy The 2nd point is that you actually have to believe the proposition. You cannot claim to have knowledge of something unless you believe it i.e. you cannot say you ‘know’ 2+2=5 because you do not believe this is true. The 3rd point is you must have sound reasons (evidence) to support your claims. You may well believe a proposition but you need to be able to justify this with supporting evidence. This evidence can come from a variety of sources: empirically verifiable (evidence that can be proved true by testing), rationally sound (we can use reason to prove it) or it comes from a trusted authority such as a text book, a teacher or the news. Look at the table below and copy and complete into your jotter. State whether the following true propositions are Empirically verifiable Rationally sound Trusted Authority Types of justification Proposition Water boils at 100 degrees centigrade Square root of 81 is 9 Urdu is spoken in Afghanistan The Sea of Tranquillity is on the Moon Pigs can fly Fire is hot and can burn you A triangle has 3 sides You can’t steal what belongs to you Eating yellow snow isn’t good All bachelors are female Stonefish are deadly The 12 most venomous snakes in the world live in Australia Type of justification Empirically verifiable Rationally sound Trusted Authority Regardless of the type of verification, the proposition must meet the criteria of the Tripartite Theory of Knowledge if it is to be counted as justified true belief. Propositions can be proved false using the types of verification showing that they do not meet the criteria of the TTK. 12 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy Look at the table below and copy and complete into your jotter. Complete the relevant boxes for the conditions you believe to be met. Pay particular attention to the ‘true/false’ and ‘justification’ columns. Write out the propositions you think meet the Tripartite Theory of Knowledge claim that for something to be counted as knowledge it must be justified true belief. Be prepared to justify your claims!!!! Justified, true, belief Proposition True/false All red roses are red True 1)All Scotsman have False ginger hair 2)Oranges are orange 3)The Earth is flat 4)Elvis is alive 5)God exists 6)2 + 2 = 4 7)Everest is the highest mountain on Earth 8)Racism is wrong Do you believe it? Yes No Justification (Is the evidence reliable?) Yes No 9)Strawberry ice cream is the best! 10)Aberdeen is south of Glasgow 11)Oban is in Europe The key question always needs to be: is the proposition justified true belief? If all 3 conditions are met then we can count the proposition as certain knowledge. It is worth noting at this stage that JTB is a working definition that philosophers use to define ‘certain’ knowledge but it is not universally accepted as many arguments are based upon the same evidence but reach opposite ‘truth’ conclusions i.e. arguments between evolutionists and creationists use the same evidence but come to radically different conclusions! 13 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy Discussion – can the theory of evolution be treated as JTB? So, if the Tripartite Theory of Knowledge (TTK) is met then we can be sure that the propositions are indeed justified, true belief? Well, no, not really. Criticisms of the Tripartite Theory of Knowledge Scepticism Sceptics are usually philosophers who maintain the knowledge can never be certain. They usually focus on the justification part of the TTK by arguing that we can never really ‘know’ anything because we can only justify our reasons up to a certain point. Sceptics are not people who deny that knowledge exists only that we can never be completely certain of the justification or evidence put forward. Sceptics list the following arguments to support their claims. 1) Gettier type problems - The problem of accidental correctness? For something to count as knowledge we have to be sure that the tripartite conditions are met but what happens if this only is true by accident. Edmund Gettier came from obscurity in 1963 (and returned to it in 1963) asking ‘if someone is accidentally correct does this count as knowledge?’ The answer is obviously no because if we are only correct accidentally or by chance, then this cannot be JTB. Look at the following examples and decide whether the conditions of JTB are met. 14 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy The Faulty Watch Alison and Susan are walking, shopping and talking in a city centre when Alison asks the Susan the time. Susan glances at her watch and tells Alison it is exactly 2 pm, However, Susan does not realise that her watch has stopped and it stopped 24 hours ago. Susan believes the watch (it tells the time), she can justify her reasons (a watch is designed to keep time) and it is true that it is 2 pm. However, she is only correct accidentally! Does this count as JTB? The Lucky Rabbit’s Foot Every time Sandra puts on a bet she rubs her lucky rabbit’s foot which is on a key ring in her pocket. Each time she does this the horse she bets on wins. One day she loses her keys and doesn’t find them in time to rub the rabbit foot before placing her bet. The horse loses and she loses her bet and says to herself, ‘I knew that horse was going to lose! I didn’t get a chance to rub my lucky rabbit’s foot.’ Is this JTB? The Hesitant Student Billy is sitting daydreaming in class. They are doing Maths and he hates Maths. Suddenly his teacher asks, ‘Billy, what is the square root of nine?’ Suddenly woken out of his daydream Billy gathers himself and answers, ‘Err, three?’ ‘Well done Billy’, says his teacher. Is this JTB? Key Questions 1) Why do sceptics argue we can never have ‘certain’ knowledge? (k/u1) 2) Which of the 3 above examples meet the conditions for JTB? Explain your answer. (a/e 6) Task In groups, or pairs, construct your own Gettier type problem. All the conditions for JTB must be met: it must be true, it must be believed and it has to have supporting evidence but it must be accidentally correct. 15 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy 2) Infinite Regress of Justification - can the justification part ever be secure? Sceptics (philosophers that think knowledge can never be certain) would continuously attack the justification part of JTB by asking ‘how do you know?’ Each piece of supporting evidence needs to be supported by other evidence and that evidence by other evidence. This is a very powerful challenge as sooner or later, justification (supporting evidence) becomes impossible. In groups, look at the following JTB propositions all of which are true. 1 person needs to play the role of the sceptic and must continually ask ‘how do you know your evidence is reliable?’ All group members are expected to get involved. Lady Gaga is female Scotland is in Europe 2+2=4 I know I exist For all of the above examples, justification eventually becomes a problem. If the evidence supporting a proposition cannot be justified then the argument collapses. Eventually the answer will be ‘I don’t know’. If this is the case the JTB fails and the sceptic wins! 3) Problems with knowledge from the senses As we have already seen, if we base knowledge on the senses then it is possible that our senses may be deceived. The plane in the sky, the star that has already exploded the pencil in a glass and the oar in water. It is possible that the knowledge we perceive to be true is nothing more than sense deception. 16 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy Task – In pairs give some examples of problems with knowledge based on the senses. 4) Problems with reason Plato suggested that we can ‘reason’ or think about absolutes through study and reflection and this will help us to identify ‘forms’. However, Plato believed that knowledge was gained in previous lives and that the soul was in constant flux of reincarnation (and there are definite problems with that theory). For Plato, it was a case of remembering previous knowledge and teasing out the knowledge we were born with. Plato thought that we are all born with ‘innate knowledge’, knowledge that we might now call instinct. Through study and reflection, Plato believed, we could recover what we already knew. However, this is problematical and not certain and his theory of the Forms does not help us to be certain and does not help JTB. Innate ideas (knowledge we are born with) include an inbuilt idea of God, knowledge of right and wrong and the ability to use language and apply maths. Innate ideas are very difficult to prove. Task – in pairs give at least 3 examples of innate ideas Discussion – is there a difference between innate ideas and instinct? 5) The problem of Authority Most of the knowledge we all have has come from or does come from some sort of Authority. We gain knowledge from books, teachers, TV, newspapers and Internet media sources etc. Sceptics would argue that there is always the possibility that the source of the 17 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy knowledge (authority) could be wrong and so we cannot rely on this type of justification as reliable. Examples of this type could be people that live in dictatorships (North Korea, Nazi Germany etc) where history is/was taught to suit the regime, where news stories suit the regime etc. Furthermore, thousands of children in Scotland have grown up with knowledge based on the media, most would think Braveheart was a name given to William Wallace but this is simply not true – Braveheart was the name given to Robert the Bruce. To further highlight the problem think about the following example – William Wallace was a Scottish freedom fighter Or William Wallace was a savage terrorist Discussion point – can we trust the media? Key Questions 1) What is the Tripartite Theory of Knowledge? (k/u2) 2) What, according to sceptics, are the problems with the Tripartite Theory of Knowledge? (k/u5) 3) Justification of knowledge claims One of the biggest problems when faced with a proposition is: how do we know whether the claim is true or false? According to the Tripartite Theory of Knowledge, the claim needs to be justified true belief. But what if we don’t know whether a claim is true or false? Look at the following proposition The highest mountain in the world is Mount Sagarmatha (29035 ft or 8850 m) – is this claim true or false? 18 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy If you have never heard of Mount Sagarmatha can you make a judgement on the proposition? The answer is no - just because we have never heard of something this doesn’t mean that it must be false. The English name of Mount Sagarmatha is Mount Everest! Does this piece of knowledge make the proposition true? ‘Mount Everest is the highest mountain in the world’ is generally accepted as being true but it is actually false. The highest mountain on Earth is Mauna Kea in Hawaii (33476 ft or 10333 m) Most of us have been taught that there are 5 senses but this is now widely regarded as false as we have around 22 different senses i.e. a sense of balance, a sense of danger or a sense of humour etc. So, it may well be that before we can determine the truth of a proposition we just need to clarify the proposition i.e. the tip/summit of Mount Everest is the highest point of land in the world is JTB. We know this is JTB because we can prove it to be true – Everest was named after the first person who measured its height – Sir George Everest in 1865. Similarly, when claiming we have 5 senses all we have to do is state we have 5 physical senses! Once we have clarified the proposition it becomes possible to prove it true or false through the supporting evidence provided. However what about propositions such as ‘God exists/God doesn’t exist’? You may believe it/disbelieve it but can you justify the belief and show that the proposition is true or false? The simple answer is no as there are no conclusive arguments either way and so neither proposition would count as JTB. Summary of scepticism So, have the sceptics won? Is it the case that knowledge can never be certain? The sceptic 5 point attack seems to be very strong. Gettier-type problems of accidental correctness Infinite regress of justification Sense experience unreliable Problems with knowledge through reason 19 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy Problems with Authority Key questions 1) Can knowledge claims be justified if we don’t know whether a proposition is true or false? (k/u2) 2) Why is clarity important when assessing truth claims? (a/e2) However, many philosophers do believe knowledge can be certain by claiming there are ways to discover knowledge if the knowledge is built upon foundational truths. Foundational Truths In order to understand what philosophers mean by foundational truth it can be helpful to think of how buildings are constructed. Every building needs to be built on a solid foundation, which usually involves digging down until stable ground (rock) is found – only a fool would try to build a house on sand as the foundations would give way and the whole structure would collapse. Philosophers approach Epistemology in the same way – find a method of acquiring knowledge that is secure and then build upon this foundation. If the knowledge foundation is secure then the knowledge that is built on this will also be secure. Rationalism and Empiricism are two approaches that are regarded as being based on foundational truths. Rationalism Rationalism holds that knowledge begins within the mind: we are all born with knowledge already in the mind and this knowledge is certain. This knowledge has not been gained through experience and is held to be innate knowledge. Rationalist philosophers (Plato, Augustine, Descartes, Leibniz and to a certain extent, Kant) believe that the best way to arrive at JTB is through the use of reason (logical thinking) and innate ideas. 20 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy Innate ideas as reflections – Plato Plato thought that knowledge was essentially innate (knowledge contained in the mind at birth) and through study and the use of reason it is possible to arrive at JTB. Plato, like many Greek philosophers, believed in reincarnation and therefore thought we are merely trying to rediscover what we have already learned in a previous life. Plato thought that there was a clear difference between appearance and reality and that there must be a way to discover the difference between the two. Plato thought that appearance was based upon sense experience and authority and that this was unreliable. Plato believed that reality could be discovered only through reason (logical thinking) and that this was certain and reliable. Plato used his theory of the forms and stories such as the simile of the cave to illustrate how reason could be used to arrive at certain knowledge and this would be foundational knowledge. Plato did believe that knowledge gained through the senses could play a role but only by confirming knowledge gained through reason. Innate ideas as divinely placed – Augustine Augustine thought that innate ideas were placed in the mind by God and were not there as a result of reincarnation. Augustine thought this because he believed in the great chain of being as found in the Ontological argument. Augustine argued that issues such as God’s existence were not in doubt as we are all born with knowledge that God does exist but how could that knowledge get there? Augustine stated it could not get there unless it was put there and the only being great enough to do this for all mankind was God. Innate ideas as being fully formed- Descartes Rene Descartes also thought that reason (logical thinking) was the key to foundational truths. Meditations was written by Descartes in order to show how reason or the intellect was the only secure 21 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy way to arrive at JTB and that the sceptics could be defeated. In Meditations, Descartes employs his ‘method of doubt’ to everything he thinks he knows: he discards all knowledge based on sense experience as being possibly false, he rejects all knowledge based on authority as this also could be wrong and he finally has to reject the obvious notion that he even has a body. Descartes does this to show that the Infinite Regress of Justification can reduce knowledge to an endless stream of problems and uncertainty. Descartes finally arrives at the point where he even doubts his own existence. Descartes believes he solves this ultimate justification by reasoning (logical thinking) that if he doubts his own existence then there must be something that is doing the doubting and that the something that is doing the doubting must exist – the Cogito or as it is better known – I think therefore I am. Descartes believes this is certain knowledge and a foundational truth that cannot be challenged by the sceptics. Descartes argues that his existence is so ‘clear and distinct’ that anything else that he perceives in this way must also be true. He ‘clearly and distinctly’ perceives that God exists and that God would not deceive him and so God acts as a guarantee that Descartes exists (Cartesian circle argument). Descartes then begins to rebuild knowledge based upon this foundational knowledge. Descartes argues that ideas surrounding his existence, God’s existence and concepts such as maths are fully formed in the mind at birth. Descartes only uses reason to establish what he believes as certain knowledge although he believes sense experience can play a role but only by confirming knowledge gained through reason. Innate ideas as potentialities – Leibniz Gottfried Leibniz gives 3 reasons for the existence of innate ideas: universal characteristics, potential and foreseeing events. 1) Ideas surrounding geometry, algebra and maths rely on universal characteristics i.e. triangles will always be 3-sided objects with a total of 180 degrees. We cannot get these universal characteristics through sense experience as triangles do not exist outside the human mind. 2) Leibniz said the mind, at birth, was like a block of marble that contained veins running through it. The sculptor needs to see 22 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy the potential within the marble before the sculpture is begun. Leibniz believed that the veins running through the mind were innate ideas that had the potential to be shaped and formed. 3) Leibniz made a distinction between people and animals by stating people were capable of foreseeing or predicting future events through reason while animals cannot. An example of this could be that we know gravity exists on our planet and that if a similar planet were discovered it would have similar gravity – animals on the other hand have no concept of the theory of gravity. Kant on morality Immanuel Kant also uses reason (logical thinking) to establish the boundaries of human behaviour. Kant believed that morality (choices around behaviour) should be established on reason (logical thinking) alone and that the consequences of an action should not play a role in determining whether the action is good or bad. Kant thought this because he believed that we cannot control the consequences of an action and therefore we cannot predict the outcome of an action. And because we cannot control or predict consequences then it is impossible to determine morality in this way as the outcomes might be different in different situations, which could allow for different and opposite views on the same moral issue. Kant argued that by using reason, we could arrive at a position that all people would recognise as being right and fair (innate ideas) i.e. that we should treat people the way we ourselves would like to be treated. Kant argues that no-one wants to be lied to, no-one wants to have things stolen from them, no-one wants to have promises broken, no-one wants to be murdered etc. So, using reason (logical thinking), Kant believes it is possible to establish correct moral behaviour and so creates foundational truths, which in turn will build fairer societies. Key Questions 1) What is meant by the term ‘foundational truth’ and why do some philosophers believe this is important? (k/u2) 2) What is meant by the term ‘innate knowledge? (k/u1) 3) How do rationalist philosophers explain the concept of innate ideas? (k/u4) 23 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy Rationalism and Infinite regress of justification As we have already seen, rationalist philosophers do believe it is possible to defeat the sceptic argument of the infinite regress of justification through reason (logical thinking) based on foundational truth and innate ideas (knowledge in the mind at birth) and that knowledge that comes from this will be certain. Rationalists would claim that truths including maths, the existence of God, knowledge of right and wrong are all present in the mind at birth. But how do they justify these beliefs? 1) Cognitive Predisposition Cognitive predisposition simply means that humans are ‘hardwired’ from birth and that this is an evolutionary/hereditary outcome. Evolutionary biologists such as Richard Dawkins believe we are born with inbuilt drivers that are a direct result of evolution. The ‘selfish gene’, for example, determines transferral from one generation to the next. It also seems that certain skills can be passed down through the generations i.e. musical ability etc. Rationalists believe that knowledge can be gained a priori (before sense experience) through the use of reason alone. So, merely by thinking rationally about something we can discover sure foundational knowledge. Look at the following example 1+1=2. How do we know this is true? Well, once we understand the concept of 1 then it is possible to understand the concept of 2. Once the concept of 2 is understood the 1+2=3 becomes purely deductive through reason. With these concepts as foundations very complex maths become an exercise of reason alone. But where does the ability to do maths come from? Rationalists argue it is from innate ideas through cognitive predisposition. 24 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy Noam Chomsky argues that language and the ability to use it is also innate. Chomsky states that the complexity of language can never be learned through experience and that we are all born with abilities to process complex language which is a cognitive predisposition. There are also vast similarities across many different societies and cultures about morality and behaviour. Rationalists would claim that these agreed rules of behaviour show innatism – why do we agree on so much? Rationalists would claim we have a cognitive disposition towards morality from birth. Finally and in a similar way, as we have seen in arguments for the existence of God, once we understand the concept of God then God must exist. Ideas of God’s existence are so widespread that we must have a cognitive predisposition to accept it. Key Question 1) What is cognitive predisposition? (k/u 1) 2) In what ways do rationalists believe cognitive predisposition defeats the infinite regress of justification? (k/u 2) 2) Deductive arguments and analytic truths Rationalists think that the infinite regress of justification can also be defeated through deductive arguments and by using analytic truths. 25 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy a) Deductive disciples such as maths and geometry are the most certain method of acquiring JTB. There seems to be little doubt that 2+2=4 and that no amount of questioning can change that particular outcome. Without getting silly, it is pointless to discuss it further. b) In a similar way, triangle is, by definition, a three-sided object with internal angles that add up to 180 degrees – triangle means three angles. Further, if the claim was made that all bachelors are male, it seems daft to question the truth of this statement because bachelor means unmarried male. Examples such as triangles and bachelors are analytically true (true by definition) and as such do not seem subject to the infinite regress of justification. Key question a) Why do rationalists think deductive arguments can defeat the sceptic infinite regress of justification question? k/u1 b) Why do rationalists think analytic truths can defeat the sceptic infinite regress of justification question? k/u1 Empiricism Empiricism, (Greek word for ‘experience) like rationalism, is a system that claims foundational truth. Unlike rationalism, empiricism is not based upon reason but upon knowledge gained through the senses – ‘empirical’ means ‘capable of being experienced by the senses’. Empiricists such as Locke, Hume and Berkeley reject the claim innate ideas exist; Locke claimed that the mind of a newborn baby was ‘tabula rasa’ (blank slate) and that all knowledge is written upon the mind as the mind starts the experience the world. This approach to knowledge is ‘a posteriori’ i.e. knowledge comes ‘after experience’. Locke argued that this was the only way we can acquire knowledge. Exercise Which of the following do you know by sense experience/could be known through sense experience and which are a priori? 26 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy A posteriori A priori 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Bannockburn happened in 1314 Santa exists 10 is greater than 9 Ice cream is cold Greece is not only a country but a musical 6. The shortest distance between 2 points is a straight line 7. How to gain attention 8. How to play the guitar 9. Psychopaths feel no emotion 10. There is life after death Empiricist rejection of innate ideas Locke and innate ideas Locke agrees with Aristotle that ‘there is nothing in the mind except what was first in the senses’. This is a complete rejection of innate as Locke argues that if innate ideas are present then the same ideas would exist for all. You will recall that we started off by discussing the difference between rationalism and Empiricism. Rationalism starts with this central idea that some of the knowledge we have is based not on experience – but on the operation of reason alone – it is innate. We just know that some things are true. Rationalists do not deny that people learn by experience, they just think that our starting point is knowledge that is hard-wired so to speak – that is already in our minds. However by the 17th century important philosophers and thinkers were questioning that idea. Science was just in its infancy, but intellectuals and thinkers were getting caught up in the idea that the world was a place that could be studied and taken apart and examined to see how it worked. The idea that we could learn to better understand the world was taking hold. A young doctor and writer called John Locke called into question the whole notion of innate ideas. He started by trying to identify an idea so basic, so fundamental that it had to qualify as innate knowledge – if such a thing existed. He started with the statement 27 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy – ‘what is, is and what is not, is not’. This basic statement about existence he argued had to be so fundamental that it must be part of innate knowledge – if such a thing existed. So we would expect therefore that if we asked children or people from other lands what they understood by the statement why then – because this knowledge is innate – they would completely understand what was meant by it. However, if they failed to recognise the statement and understand its meaning – it would indicate that there was no such thing as innate knowledge. Locke did not conduct a full-blown survey of people for this ‘test’ but he was satisfied that on the whole people did not recognise immediately what the statement meant and that in turn meant that there was no such thing as innate knowledge – the key idea of rationalism. Instead, Locke argued, we are all tabula rasa – blank slates – upon which experience writes. In other words, all knowledge arises from experience. In modern day language, if there are innate ideas about morality and the existence of God etc. then why do people have such different notions of what these things are and why do some not share these ideas at all? David Hume Hume follows up on Locke’s work by agreeing that innate ideas are not present in the mind at birth – that the mind is indeed tabula rasa at that point. Hume claims this is because it is not possible to have knowledge of something without first having experienced something ‘a posteriori’. Hume calls these experiences impressions and argues that only when we have an experience can the mind (reason) make sense of it. What Hume is suggesting here is that there can be no ideas unless there have already been impressions. The man who has been blind from birth will have no idea of the colour. A deaf person cannot have any idea of sound but if they were somehow cured then they would have no problem gaining knowledge of what these 28 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy things are like. Hume also argues that Laplanders or Negros would not know what wine tasted like or that a selfish person couldn’t understand generosity. A modern day spin on this could be ‘could a tribesman in a remote African country tell you what Irn Bru tasted like if they had never tasted it themselves?’ So, for Hume, innate ideas did not exist as all knowledge present in the mind is based on experiences through the senses. Key question a) Why did Locke reject the notion of innate ideas? Give 2 examples to illustrate your answer. k/u3 b) Why did Hume reject innate ideas? Give 2 examples to illustrate your answer. k/u3 Empiricist emphasis on sense experience and a posteriori knowledge Empiricism is based upon the foundation of knowledge through observation and through the senses. Empiricism is the method used by science and medicine and is responsible for most of the technological advances made by the human race. A posteriori knowledge is entirely inductive as it looks to gain knowledge from things we can experience through the senses. And because it is inductive it makes no claim of guaranteed knowledge merely that the knowledge is probable. Think about how experiments are conducted in a lab – things are tested and the results recorded. If the test is repeated enough times then the results are thought of as being reliable. When new drugs are being developed then these drugs are tested in many different ways to ensure they are safe for use. In many ways, scientists and specialists, need to verify results in order to prove the conclusions are not false before they can accept the conclusions as being true. So, through a process of testing, new knowledge is gained but this is only possible a posteriori. 29 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy Task In small groups, explain the process that would need to be followed if you were going to bring a new product to the market i.e. a shampoo, a ready meal or a ‘run flat’ tyre for a car. Empiricists favour a posteriori knowledge over a priori knowledge as they believe subjects such as Biology and Physics can lead to new knowledge through testing and observation while subjects such as Maths and Geometry are merely abstract facts that do not give us any new knowledge. A triangle may have 3 sides with internal degrees adding up to 180 but this isn’t really helpful in discovering new knowledge. The statement ‘all bachelors are unmarried males’ is definitely true but it does not give us any new information – merely a definition. The statement ‘it is either Monday or it is not’ is true but not very helpful if you want to find out what is on T.V. ‘If it is Monday then EastEnders is on at 8pm or if it is Tuesday it is on at 7.30pm’ is also true but it is not until we know what day it is that we will be able to watch at the correct time. Key question a) Why do empiricists emphasize sense experience and a posteriori knowledge over a priori rationalism? k/u2 b) Empiricists argue that Biology and Physics are better subjects than Maths and Geometry. Why is this the case? k/u2 (other supermarkets are available) The role of reason in empiricism Empiricists argue that reason does have a role to play but only in making sense of the experiences we have. This takes the form of inductive reasoning. 30 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy Questions – why do we buy food days in advance? Why do supermarkets employ weather forecasters? Why do teachers give predicted grades for Higher pupils? In all three cases the answer is fairly clear – past experience leads us to believe the future will resemble the past! We shop in advance because we know we will be hungry in the future: supermarkets know, depending on the weather, certain items will be in more demand i.e. salad in summer, chocolate at Easter and alcohol at New Year! Our minds link the events through reason and come to a conclusion. Traffic lights in the UK follow a set sequence and through teaching and experience we understand through reason what will happen. However, in different countries the sequence is not exactly the same but after experiencing the sequences our mind reasons the differences and we adapt very quickly. Scientists use the same method when analysing results – reason makes the connections. If scientists were trying to find out the greediest pupil in the room they would test it in this way. Veronica, Amanda, Heather and Paula would have a jar of sweets placed in front of them. Veronica scoffs the lot, Amanda doesn’t have any and the others have three each. The basic connection reason makes is that Veronica is the greediest. However, judgements, through reason, could be made on hunger, health, obesity and character! Key question What role does reason play within empiricism? Illustrate your answer with an example? k/u2 Problems with Empiricism The senses, on which knowledge is based, can be deceived. Sceptics attack empiricism for the following reasons. 31 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy Optical Illusions – see PowerPoint If we based our knowledge on the senses then it is entirely possible that our senses will mislead us. The plane in the sky is much further ahead than we think, the star that has already exploded, a pencil in water or the H.I.V virus. This knowledge is not certain! Hallucination This is when we think we see or hear things but they aren’t actually there. When we have a fever we can be convinced something is real but it is not or when we are gripped by fear we are certain someone is looking at us! Physical laws of the Universe We can’t always observe what is going on in the universe! Gravity exists but we can’t see it, infra-red and ultra-violet light cannot be seen by the human eye. What if there are others things we don’t yet know about and how can we be sure of a knowledge claim if we don’t know what we are looking at. Theory-laden assumptions We all see things in slightly different ways and so can interpret things in a different way – we make judgements based on what we already know or on what we think we already know. A trained musician looking at a musical score will have a completely different interpretation of the dots from someone who cannot read music! The problem of Induction A posteriori knowledge is highly dependant on inductive reasoning – the future will resemble the past! Hume points out that assuming the future will resemble the past is not reliable because cause and effect are not necessarily linked. One specific cause can produce lots of different effects none of which are guaranteed to happen every time 32 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy the cause occurs. Think back to the examples of shopping in advance, of supermarkets employing weather forecasters and why teachers give predicted grades for Higher pupils? It is simply not the case that because you have been hungry every Thursday in your whole life that you will be hungry this Thursday. It is not true that people always but according to the weather or seasonality and it is entirely possible that a teacher may estimate as ‘A’ grade based on all the previous evidence but the pupil is not guaranteed that grade. At best, induction only gives probable knowledge not guaranteed knowledge. Key question Why do sceptics dismiss empiricism as unreliable? k/u5 How do empiricists deal with the sceptics claim that knowledge can never be certain? The simple answer is that they cannot – well not fully. Empiricism is based upon inductive reasoning through a posteriori experiences. The claim is never about guaranteeing knowledge merely that the knowledge is highly probable. By testing, measuring, recording and repeating the process, empiricism is about exploring the boundaries of what we know. The best defence against claims of infinite regress are that empiricists are aware that the senses can deceive but because they are aware of this then they can guard against it through verification and testing. Coherentism Unlike Rationalism and Empiricism, which are essentially foundationalist views of knowledge (although it is possible to argue you can be a rational coherentist and an empirical coherentist), Coherentism is a non-foundational approach to knowledge. Rationalism and empiricism both try to find knowledge which is reliable and then build links from that knowledge to other things. This method sets up a sort of chain-linking system where one piece of 33 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy knowledge can lead directly to another e.g. Rationalist claims of innate knowledge lead to claims about morality and the existence of God and Empiricist claims of knowledge through a posteriori means leads to claims that are at worst highly probable. Foundationalism Perhaps the chain begins with a belief that is justified, but which is not justified by another belief. Such beliefs are called basic beliefs or foundational beliefs.. An analogy to explain this idea compares foundationalism to a building. Ordinary individual beliefs occupy the upper stories of the building; basic, or foundational beliefs are down in the basement, in the foundation of the building, holding everything else up. In a similar way, individual beliefs, say about morality or ethics, rest on more basic beliefs, say about the nature of human beings; and those rest on still more basic beliefs, say about the mind; and in the end the entire system rests on a set of beliefs, basic beliefs, which are not justified by other beliefs, but instead by something else. This means that there must be some statements that, for some reason, do not need justification. For instance, rationalists such as Descartes and developed ideas that relied on statements that were taken to be self-evident: "I think therefore I am" is the most famous example. Similarly, empiricists take observations as providing the foundation for the series. Foundationalism relies on the claim that it is not necessary to ask for justification of certain propositions, or that they are selfjustifying. If someone makes an observational statement, such as "it is raining", it does seem reasonable to ask how they know—did they look out the window? Did someone else tell them? Did they just come in shaking their umbrella? Coherentism insists that it is always reasonable to ask for a justification for any statement. Coherentism contends that foundationalism provides an arbitrary spot to stop asking for justification and so that it does not provide reasons to think that certain beliefs do not need justification. 34 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy Foundationalists support their idea by claiming that sense experience can be a belief in itself. For example, suppose that someone claims that they had fallen and scraped a knee as a child. With no witnesses or other records, there is no fact which can support this belief except that they remember it. In effect, the belief that they scraped there knee is supported only by the memory of having scraped the knee. Ultimately, then, this sensory belief is justified by another belief, that the memory is reliable and true. Coherentism is the belief that an idea is justified if and only if it is part of a coherent system of mutually supporting beliefs (i.e., beliefs that support each other). In effect Coherentism denies that justification can only take the form of a chain. Coherentism replaces the chain with a holistic approach. Coherentism is a rival theory of justification to foundationalism. Unlike foundationalists, coherentists reject the idea that individual beliefs are justified by being inferred from other beliefs. Instead, according to coherentism, whole systems of beliefs are justified by their coherence. What is Coherence? Coherence consists of three elements. A belief-set is coherent to the extent that it is consistent, cohesive, and comprehensive. Consistency A belief-set is consistent to the extent that its members do not contradict each other. Clearly a belief-set full of contradictory beliefs is not coherent. Consistency, however, need not be an all or nothing affair; beliefs may be in tension with each other, without being strictly speaking contradictory. Tensions of this kind, like contradiction, reduces the coherence of a set of beliefs. Think about the belief that your parents really are your parents! If you look like one of them or have certain characteristics from your 35 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy parents then this would be consistent with the belief. However, if both your parents were white and you were black then the evidence may be seen as somewhat inconsistent with the belief but not necessarily false as there may be an explanation! Cohesiveness Mere consistency is not enough for coherence. For a belief-set to be coherent, the beliefs that it contains must not only be mutually consistent, but must also be mutually supportive. A set of beliefs that support each other, where one belief makes another more probable, is more coherent than a set of unrelated, but consistent beliefs. The belief that your parents really are your parents is based upon many factors: family, friends, upbringing and legal documents. Each of these factors re-enforces the other and make the belief stronger. Comprehensiveness Finally, coherence involves comprehensiveness. Comprehensiveness, of course, is a not a part of the meaning of coherence in the ordinary sense. In the context of coherentist theories of justification, however, a belief-set increases in coherence as it increases in scope; the more a belief-set tells us about, the more coherent it is. Parents again! The more evidence we have then the more comprehensive the evidence becomes. Objections to Coherentism: Coherent Alternatives Coherentism holds that beliefs are justified by belonging to coherent belief sets. There are many possible coherent beliefs sets, however, and coherentism provides no way of deciding between them. Fictional worlds such as Narnia, the Matrix, and the Discworld are as coherent (or at least could be made as coherent) as the actual world. If coherence is the standard of justification, 36 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy therefore, then we are as justified in believing in the Discworld as we are in believing in Earth, so long as we are willing to make the necessary adjustments to our other beliefs. This, though, is absurd. Moreover, many of these belief sets contradict each other; there are coherent belief sets that contain the belief that the world is round, and there are other equally coherent belief sets that contain the belief that the world is flat. In order to decide whether the world is round or flat, therefore, I must use some other standard of justification than coherence. In fact, for every belief there is a coherent belief set that contains it, and so coherentism fails to recommend any belief over any other. It can’t help us at all in deciding what to believe. A belief-set can be coherent even if all of its members are false. The belief that your parents are aliens coheres very well with the belief that they keep a flying saucer in the garage, which coheres very well with the belief that the FBI have dispatched agents to investigate, etc. Despite the coherence of this belief set, however, none of these beliefs is true. Justified beliefs, because they are justified, are more likely to be true; the whole point of seeking justification for our beliefs is that justification is truth-conducive. The mere fact that a set of beliefs is coherent does not imply that its members are true. In fact, there are more false coherent belief sets than there are true coherent belief sets. Key questions a) Explain the difference between foundational claims and non-foundational claims in Epistemology? Give examples to illustrate your answer. k/u5 b) What are the objections to Coherentism? k/u5 37 Higher/Intermediate 2 Philosophy 38