The Vermont Eugenics Survey and the Western Abenaki Indians

advertisement

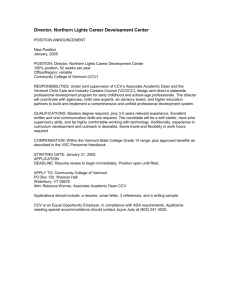

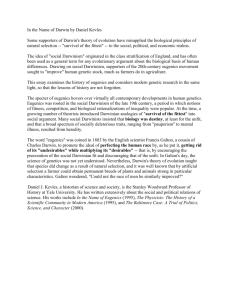

The Vermont Eugenics Survey and the Western Abenaki Indians: How the Sterilization Movement Impacted the Tribe and their Fight for Recognition Nicole Vendituoli Summer 2006 Social Sciences Research Center 1 Table of Contents I. II. III. IV. V. VI. VII. VIII. IX. X. XI. XII. XIII. Preface Introduction Eugenics in Vermont Adjusting to Changing Times The Abenaki and the Eugenics Survey Abenaki Population and Tribal Membership Background on Sterilization Petition for Recognition Using the Vermont Eugenics Survey as a Tool to Achieve Federal Recognition The Eugenics Survey In Regards to the Bureau of Indian Affairs Decision on Recognition Conclusions Bibliography Appendixes 2 Preface When I originally undertook this research project, I planned to conduct a series of interviews with members of the Abenaki tribe. In order to do this through the proper channels, I contacted Chief April Rushlow to gain her permission and make her aware of my project. Over the summer spent doing my research, I wrote three times, and did not receive any response from Chief Rushlow. My project was forced to take a different direction because of this unforeseen development and I instead focused on the petitions for recognition and the responses provided by the state of Vermont and the Bureau of Indian Affairs. This altered my paper in such a way that it became an analysis of already published materials, instead of a first person account of events. This paper also is distinctly one-sided for the sole reason that I was unable to obtain the Abenaki perspective and position. In other words, the data may be biased because a lack of Abenaki input. I personally remain open-minded about the topic, but have presented the information that I was able to gather and the conclusions that were developed by the BIA and the state of Vermont in regards to the Vermont Eugenics Survey and how that was used in the fight for recognition. It is of importance to note that the box of materials containing the lists of people sterilized by the state of Vermont as a part of the Eugenics movement has gone “missing.” The state archivists do not know what happened to it, but even if it were to be located, the information contained in those files is considered confidential due to the delicate subject matter. If this information was available, it would provide a concrete answer as to whether or not the Abenaki people were 3 targeted by the Eugenics Survey, but since it is not, we must rely on other sources of material and information. 4 Introduction People often think of history as a collection of facts, but often there are areas of grey that result from incomplete or conflicting data. These conflicting accounts allow historians to draw conclusions and to speculate about what actually happened. These “grey” areas are often thought of as history’s mysteries. Vermont has its own share of mysteries and dark secrets, including the Eugenics Survey of the 1920s and 1930s. The results of the survey can be felt in every town and corner of the state, but due to the sensitive nature of its content, it is rarely discussed. One group of people residing in Vermont has argued that they were specifically targeted by the Vermont Eugenics Survey: the Western Abenaki Indians. The Western Abenaki Indians reside in Vermont and New Hampshire, but are primarily located in the area around Lake Champlain. Those living in the Lake Champlain area are generally members of the Sokoki/ St. Francis tribe. The native Abenaki language is Algonquin, and the English translation for Abenaki is “people of the dawn.”1 Over their long history, the Abenaki have made multiple attempts to become recognized by the state of Vermont and the Federal Bureau of Indian Affairs. Their efforts were seriously renewed in the 1970’s, and since then, they have been faced with constant political struggle. In November 2005, the Federal Bureau of Indian Affairs declined to acknowledge the Abenaki as an official Indian tribe, but that did not stop them from pursuing other avenues 1 William H. Sorrell and Eve Jacobs-Carnahan, “State of Vermont’s Response to Petition for Federal Acknowledgment of the St. Francis/ Sokoki Band of the Abenaki Nation of Vermont,” (2002), 2. 5 towards some form of recognition. Their efforts reached fruition on May 3, 2006 when the Vermont Legislature passed Bill S.117 which recognized the Abenaki people, and Governor Jim Douglas signed it into law. While the recognition process was ongoing and the history of the Abenaki people analyzed, the Abenaki connection to the Vermont Eugenics Survey was established. The Abenaki used the Eugenics Survey as a tool to fight for their recognition, while also claiming that they were specifically targeted by the survey. From this, they concluded that had they not been targeted by the survey, they would not have had to hide their Indian ancestry for several decades of the 20 th century. The purpose of this research paper is to explore the connection between the Abenaki Indians and Vermont Eugenics survey, which also lends itself to a discussion of the Abenakis’ efforts to gain recognition both from the state of Vermont and the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The available evidence shows that the Abenaki Indians were not specifically targeted by the Eugenics Survey, but as noted in the preface to this paper, the Abenaki perspective, as well as valuable state evidence is missing from this analysis. Eugenics in Vermont Mid-nineteenth century America flourished, and boatloads of immigrants arrived on our shores everyday. They came from a wide variety of different countries, had many unique cultures, and brought with them a plethora of native tongues. While industrial employers welcomed their presence, many “native born” Americans resented them, and felt that immigrants were responsible for all of the country’s problems, including a rising rate in mental deficiency. At the 6 same time, a new scientific movement was on the rise, poised to address the immigrant problem. Eugenics had been developed in Europe, and it “applied the concepts of scientific plant and animal breeding to humans.”2 When you took these principles and combined them with the contemporary wisdom of racial and ethnic superiority and inferiority, it appeared that a solution had been found. Eugenics was praised as the way to protect Americans from the invasion of undesirable ethnic traits that were quickly closing in on them.3 American scientists looked to Vermont “as the last ‘great white hope’ of New England. This area seemed to be a New England without the increasing tide of ethnic “others” that plagued the coastal urban zones.”4 As a result of this perception, the Commission on Country Life was created in the 1920s to study, and perpetuate this image. A part of this plan was to deny the existence of the Abenaki Indians, since they were seen as a flaw in Vermont’s lily-white image. The Vermont Eugenics Survey was organized in 1925, under the leadership of Henry F. Perkins, professor of zoology at the University of Vermont. There were three main purposes for the survey: to conduct eugenics research, to educate the public on those findings, and to generate support for social legislation that would aim to reduce the number of “inferior” people in Vermont. 5 The first three years of the Survey focused on gathering information that would support campaigns for negative eugenics, such as sterilization, colonies for the 2 Frederick Matthew Wiseman, The Voice of the Dawn: An Autohistory of the Abenaki Nation (Hanover: University Press of New England, 2001), 146. 3 Wiseman, 146. 4 Ibid. 5 University of Vermont, “The Eugenics Survey of Vermont 1925-1936: An Overview, “ Vermont Eugenics: A Documentary History, 2001, <http://www.uvm.edu/~eugenics/overview.html> (31 May 2006). 7 feebleminded, and an increase in the use of mental testing among the population. Families were identified for further study for a variety of reasons, which included: family reputation, community rejection, case files of state institutions and child rescue initiatives from the previous decade. Information was gathered on these chosen families through interviews and correspondence. The information was then organized into pedigree charts and summarized so that the “bad seeds” in each family could easily be identified.6 Families who were targeted by the survey were labeled negatively by society, and the ramifications of the survey were felt for years after its completion.7 The Eugenics Survey closed in 1936, after its main benefactor decided to no longer fund the enterprise, but eugenics research continued in the state under the supervision of the Department of Public Welfare. Adjusting to Changing Times In the beginning of the 20th century, the Abenaki people began to realize that society was changing around them and that adaptation was necessary. Their adaptation varied in a variety of ways; from limited assimilation to total immersion in mainstream culture. Frederick Wiseman writes, “Each family band came to a new consensus about how to endure, since to remain unchanged in our old villages quickly invited genocide.”8 This may be an exaggeration, since genocide is a very strong term, defined by the United Nations on December 9, 1948 as: University of Vermont, “Family Studies of the Rural Poor: 1925-1928,“ Vermont Eugenics: A Documentary History, 2001, <http://www.uvm.edu/~eugenics/famstudies.html> (1 June 2006). 7 University of Vermont, “1925-1928: The Search for “Bad Heredity” in Vermont: “Pedigrees of Prejudice”, “ Vermont Eugenics: A Documentary History, 2001, <http://www.uvm.edu/~eugenics/overview1.html> (31 May 2006). 8 Wiseman, 115. 6 8 In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group as such: (a) Killing members of the group; (b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; (c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; (d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; (e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.9 By using the term genocide, Wiseman implies that there was an effort to destroy all of the Abenaki people in Vermont. No specific examples are given of why he implies that a genocidal policy was created towards the Abenakis, but he does appear to believe that the Abenaki people themselves lived in fear of being killed, and this is why they felt the need to go into hiding or adapt to Vermont culture. There were five different options for Abenaki families during this time period. They could exile themselves, fade into the forests and marshes, live the “Gypsy”/ “Pirate”/ “River Rat” life between Native and European culture, merge with the French community, or “pass” into Anglo-American society.10 According to Wiseman, the majority of families blended in with the working class French of Vermont, but other family bands chose to take a different route.11 The Pirates and River Rats were river-and-lake-oriented Abenaki families, and their nickname depended on their location (River Rats in Swanton, Vermont, versus Pirates in Grand Isle County, Vermont). The Pirates lived on their boats on Lake Champlain, while the River Rats lived in shantytowns on the side of rivers. Wiseman contends that in order to protect their traditional sovereignty, they 9 Frank Chalk and Kurt Jonassohn, The History and Sociology of Genocide (London: Yale University Press, 1990), 44. 10 Wiseman, 115. 11 Ibid., 139. 9 sought out land that would not be desired by the “Europeans.”12 This lifestyle declined during the 1930s, but some families continued to live on the margins until the 1950s, when government began to restrict their subsistence hunting and fishing on a more regular basis.13 The other group that requires more explanation is the Gypsy bands. They lived in upland environments, usually in tarpaper shack shantytowns. In addition to their homes, they also had a wagon and horses to draw the wagon so that they could remain mobile. Each year they followed a geographic circuit where they sold the crafts and other goods, such as baskets, that they produced during the cold winter months.14 There is a good deal of speculation among the academic community as to whether or not the Gypsy people were Abenaki Indians or simply transient Vermonters/ Canadians. This confusion is expressed by the fact that the “Gypsies” are often referred to by a variety of names. To tourists they were called “Indians,” to their Vermont customers they remained “Gypsies,” to the people that they lived with they were “French,” and they called themselves “Alnoba.”15 This has made them difficult to trace (probably on purpose) and these problems will likely take a considerable amount of time to come to terms with and solve. The Abenaki and the Eugenics Survey In recent years, some historians have claimed that the Abenaki Indians were targeted by the Vermont Eugenics Survey, and that it was an organized 12 Ibid., 120. Ibid., 131. 14 Wiseman, 138. 15 Wiseman, 139. 13 10 effort by the state to reduce their numbers, and presence in the state. Rhetoric is abundant on both sides of the argument, which makes it difficult to conclude how much the Eugenics Survey, if it at all, affected the Abenaki Indians. One of the reasons why the Abenaki’s were perceived as different was because many of them were Roman Catholic, which went against the traditional Protestant background of New England. Many of the Abenaki also had dark eyes, skin and hair that set them apart from their neighbors. The Abenaki way of life was manifested in “communalism, social and genetic isolation, subsistence hunting and fishing, disregard for increasingly restrictive laws and social programs, and the persistence of a seasonally mobile lifestyle”16 which further segregated them from the general Vermont population. All of these differences brought attention to the Abenakis in ways that may have been detrimental to their society. In his work, The Voice of the Dawn, Fred Wiseman claimed that the Vermont Eugenics Survey group quickly began to focus their efforts in on the Abenakis. In the Eugenics Survey papers, Wiseman believes that the Abenaki were referred to as Gypsies, Pirates, and River Rats, rather than simply calling them Abenaki Indians, which explains how the Abenaki could be targets of the Survey without being explicitly mentioned in the Survey’s papers. Wiseman also claims that Gypsies and Pirates, who were really Abenaki families, had their children taken away from them, and as a result, “Any family who still had thoughts about standing forth as Abenaki… quickly retired to obscurity as the tide of intolerance rose.”17 If Abenaki families truly believed that losing their children 16 17 Wiseman, 147. Wiseman, 148. 11 was a possibility, it does make sense that they would hide their heritage in order to remain safe, and this is the argument that Wiseman presents. In 1931, the Vermont State legislature passed An Act for Human Betterment by Voluntary Sterilization. Wiseman argues that this law brought sterilization to the Abenaki people. In his studies, he identifies specific families who were singled out and harassed by the Vermont Eugenics Survey because they were different. He then goes onto mention that over 200 people were sterilized in Vermont under this law, but does not make any direct correlation between those sterilizations and the Abenaki people. Instead, he does make the point that the racism in that period and the law permeated into Abenaki society, and led the Abenaki to feel shame at being different and fear what would happen if they were discovered to be Abenaki by the state of Vermont.18 Within the existing Vermont Eugenics Survey’s materials, there are several references to Native Americans. One of those papers was entitled, “Special Capacities of American Indians,” and was written by W. Carson Ryan Jr., (date unknown) of the US Indian Service. It is interesting to note that this document praises the American Indian, rather than discriminating against them. It is worth quoting in length as evidence that it is unlikely that the Abenakis were targeted for sterilization by the Vermont Eugenics Survey: Indians are not inferior. Traditional ideas of the mental superiority or inferiority of races, including Indians, which had a revival during the early years of American intelligence measurement, have recently been subjected to a more discriminating analysis at the hands of competent psychologists, such as T. R. Garth, who now says that “we have never, with all our searching, “found indisputable 18 Wiseman, 148-149. 12 evidence for belief in mental differences which are essentially racial.”19 The article goes onto praise Indian arts and culture, and explaining how valuable to society they are. This may be speculation, but if the Vermont Eugenics Survey planned to destroy the Abenaki population, they would not have kept records of articles praising the value of Native Americans, nor would they have believed that the Abenakis were “inferior” when they were presented with scientific evidence that they were in fact not. Abenaki Population and Tribal Membership Population figures for the Abenaki people of Vermont have the potential to help solve a variety of mysteries: how large their community actually is, if they were indeed effected by sterilization programs (low birthrates), and if they should be recognized as a federal or state tribe. Unfortunately, these figures vary widely based on the collection agency, and no one consensus has been reached. 20 Data from the early twentieth century is relatively sparse, and it isn’t until the 1970s and the Indian resurgence movement, that few efforts were made to identify the various members of the Abenaki tribe. On the Swanton, Vermont town birth records, there were several children who were identified as IndianWhite between the years of 1904 and 1920. The Abenaki themselves hypothesize that the reason for the appearance of their Indian identity was because of Cordelia Brow, an Abenaki midwife, who filled out the original W Carson Ryan Jr, “Special Capacities of American Indians,” in Vermont Eugenics Survey files. 20 Detailed census information, charts and graphs are included at the end of this paper. 19 13 records.21 This evidence was used to support the Abenakis claim that they were a continual presence in Vermont in the early twentieth century, but the birth record forms are difficult to interpret, due to inconsistencies in handwriting and racial categories, which caused historians, and the government, to regard the information with skepticism. The relationship between population size and the topic of this paper, the Vermont Eugenics Survey, lies in the fact that the Abenaki population would have a difficult time expanding if they were the victims of forced sterilization. It is obvious that the Abenaki were not destroyed, but it would make sense that their population statistics would grow very slowly if their men and women had been sterilized. As was mentioned previously, it wasn’t until the 1970’s that abundant population data became available, but one can see that the population then began to spike, and has continued to do so with every census count since then. In particular, the formal membership of the St. Francis/ Sokoki band has increased since 1976 as more families and relatives have filled out enfranchisement forms and gained formal membership status. At the time of the Tribes Petition for Federal Recognition, the Tribe had a membership of 935 adults and 750 children under the age of fifteen.22 The majority of those members, two-thirds of the total population, live in three towns in Franklin County: Highgate, Swanton, and St. Albans, all of which are a part of the Abenaki Nation of Vermont, “A Petition for Federal Recognition as an American Indian Tribe,” Submitted to the Bureau of Indian Affairs (October 1982), 147. 21 22 Abenaki Nation of Vermont, 116. 14 Abenakis historic land area.23 In contrast to the membership figures presented by the Abenaki people, the United States Census has regularly underreported the number of Native Americans living in Vermont, but those numbers continue to dramatically rise with every new census. The Abenaki explain this in the following way: This dramatic increase can be largely attributed to the activities of the Abenaki Tribal Council and the resulting changes of attitudes among Native Americans throughout the state who became increasingly willing during the last decade to identify themselves as American Indians.24 The discrepancies between Abenaki membership counts and Federal Census numbers can be clearly seen in the chart listed below. The Abenaki claim that the number differences can be attributed to the fact that the Census Bureau has difficulty in recording minority groups due to frequent changes in address, above average rates of illiteracy and a general lack of interest.25 Location Swanton Highgate St. Albans Franklin & Grand Isle Counties Current Membership (adults only) 334 142 160 723 1980 U.S. Census Difference in members 182 91 92 444 152 51 68 279 The first major increase in population happened in 1970, when the Census recorded 229 Native Americans living in Vermont, up from 57 the decade before. The state of Vermont rationalized this in the following way: “These figures may reflect a new consciousness of Vermonter’s Indian ancestors. It is striking, 23 Abenaki Nation of Vermont, 118. Abenaki Nation of Vermont, 119. 25 Ibid. 24 15 however, that the large increase in reporting did not reveal a concentration of Indians in Franklin or Grand Isle counties…”26 Another interesting discrepancy is that that in 1975, the Boston Indian Council’s Manpower census reported 1,700 Native Americans living in Vermont, and that 80 percent of them were Abenakis. This is in contrast to the Federal Census of only five years prior (1970) that had 229 Native Americans in the state.27 The explanation that William Haviland, the author The Original Vermonters: Native Inhabitants, Past and Present, gives for this is that between 1970 and 1975, there was a resurgence of pride among Vermont’s Abenakis. He says, “It was not until after a rise of Native American activism throughout the part of indigenous peoples to stand up for their human rights—that they were ready to declare publicly what they had known themselves to be all along: Abenakis…”28 No matter what the explanation for these population increases are, the Abenaki people are making their presence in the state known, and will continue to do so in the future. The Abenaki’s increased presence can be seen from the wealth of newspaper articles that have focused on them over the last few years. The most pertinent of those relate to the size of the Abenaki population. In 1980, 1,074 Vermonters identified themselves as American Indians, but in 1990, that number had increased by more than sixty percent.29 This was fantastic news for the Abenaki community, but then in 1998 they learned that the Vermont American 26 Sorrell, 109. William Haviland, The Original Vermonters: Native Inhabitants, Past and Present (Hanover: University Press of New England, 1994), 247. 28 Haviland, 247. 29 Richard Cowperthwait, “Abenaki Count Stressed: Panel vies for accuracy in Census,” Burlington Free Press, 24 September 1999, sec. B. 27 16 Indian population had decreased by 11.5 percent in the years from 1990 to 1998.30 This simply didn’t make sense and in 1999, the Burlington Free Press wrote: “Members of the Abenaki nation, based in the Swanton area, are perplexed by the latest Census estimates. They say after decades of feeling ashamed of their heritage, more and more Vermonters are identifying themselves as American Indians.”31 This sentiment was repeated eight years earlier, in 1991, when another Free Press author wrote: “Most people agree that there are not that many more Indians in Vermont now than in 1980. Instead, most experts attribute the increase to a larger number of people reclaiming their Indian heritage.”32 This reclaiming of heritage has brought the Vermont Abenaki population up to over 2,000 people33 according to William Haviland, the author of the Original Vermonters. Now that the Abenaki have gained state recognition, it is possible that they will experience another renewal of energy and spirit that ultimately will add numbers to their membership rolls. In their efforts to become a federally recognized American Indian Tribe, the Abenakis were told that they had to provide copies of their membership roles and criteria for membership to the Bureau of Indian Affairs. They complied, but problems arose from the fact that membership was not formalized until 1975. The BIA was trying to look for a continued Abenaki presence in the state from 1900 on, but for seventy-five of those years, they had no idea as to who was and Michael Corkery, “Abenaki doubt Census Numbers,” Burlington Free Press, 15 September 1999, sec. A. 31 Ibid. 32 Laura Decher, “Figures show Indians have toughest route in VT,” Burlington Free Press, 7 July 1991, sec. A. 33 Haviland, 260. 30 17 wasn’t a member. After 1975, members of the Abenaki tribe were issued membership cards and their names were placed on file cards, but no membership rosters or lists were created. More cards were added to the collection as needed, or were removed in the case of death.34 Membership lists were eventually created for the tribe, and the 1995 list contained 1,257 names of adults and children, which included seven double entries, and one triple entry, which made the correct count 1,248.35 Since then the membership numbers have varied considerably from 1,257 in 1996, up to 1,361 in May 2005, and only three months later it fell to 1,171.36 Note: Please see census data and figures for counties in Vermont. Over the years, the Abenaki have amended their requirements for tribal membership. In their original petition for federal recognition, they had five different criteria for membership. These criteria are as follows: 1. Any person of Abenaki descent, whether through the male or female linde, who is not currently a member of another recognized North American Indian tribe, is eligible for membership in the St. Francis/ Sokoki band of the Abenaki nation. 2. In the absence of documented verification of Indian ancestry, membership in a family with long-standing local community recognition as Indian shall make a person eligible for membership 3. Other individuals who claim Abenaki descent, and who are closely affiliated with or related by marriage to current band members shall also be eligible for membership. 4. The Tribal Council shall be responsible for determining all membership. 5. The Tribal Council may adopt into the band and nation any Indian or non-Indian as they so choose.37 34 Abenaki Nation of Vermont, 169. James E. Cason, “Summary under the Criteria for the Proposed Finding on the St. Francis/ Sokoki Band of Abenakis of Vermont, “ (9 November 2005), 141. 36 Cason, 143. 37 Abenaki Nation of Vermont, 168. 35 18 Apparently, the BIA had some questions about these criteria, because in their Second Addendum to the Petition for Federal Recognition as an American Indian Tribe, they were revised. The first three criteria remained intact, but a new clause was added that said that the Tribal Council could not authorize the enfranchisement of any adult Indians or non-Indians by adoption or by honorary membership.38 It appears that they were trying to accurately discover who belonged on their membership roles, while at the same time, prevent questionable Indians from being admitted to those roles in the future. Background on Sterilization Scholars have claimed that the Abenaki were targeted by the Vermont Eugenics Survey and were actively sterilized during the 1920’s. To better understand this claim, it is helpful to have a basic understanding of the sterilization movement in the United States. During this time period, the belief existed that human races had been produced by degeneration from an original type, and that color showed how degenerated a person was.39 In relation to Native Americans, this meant that they were degenerate, because they often had a darker skin tone. This added to the prejudices that people felt already, and gave the sterilization movement even more power. Once the movement to put sterilization bills into action began, it picked up speed very quickly. Between 1907 and 1913, legislatures in sixteen states passed sterilization bills, of which four (Pennsylvania, Vermont, Oregon, and 38 Abenaki Nation of Vermont, “Second Addendum to the Petition for Federal Recognition as an American Indian Tribe: Genealogy of the Abenaki Nation of Missiquoi,” (11 December 1995), 3. 39 Philip Reilly, The Surgical Solution: A History of Involuntary Sterilization in the United States (London: The John Hopkins University Press, 1991), 5. 19 Nebraska) were vetoed by governors. The twelve states that put sterilization laws into place were: Indiana, Washington, California, Connecticut, Nevada, Iowa, New Jersey, New York, North Dakota, Michigan, Kansas, and Wisconsin.40 A note of interest is that in the majority of legislatures, the vote was overwhelmingly favorable and with the exception of Vermont, the governors’ vetoes most likely contradicted popular sentiment.41 By 1926, twenty-three states had sterilization laws on their book and seventeen states had active programs that resulted in the sterilization of some 6,244 people.42 Several parts of sterilization legislation and general discussion were focused on Native Americans. African Americans were disproportionately targeted for sterilization due to their color, but African Americans and Native Americans often mixed together, creating a unique racial mix and they were targets as well. As a result, the Pocahontas exception came into being, which created a loophole for remnants of the original Indians who had lost their Indian identity and had mixed with African Americans.43 Walter Plecker, a Virginia state legislator, was determined to deny white status (and thus avoid sterilization) to any Indian who had any African American ancestry. He was convinced that many Indians had just as much African American blood in them as they did Indian blood, and that they should be considered colored, not Indian. In 1930, he convinced the Virginia state legislature to amend its race law so that “Every 40 Reilly, 39. Reilly, 45. 42 Reilly, 67. 43 Reilly, 73. 41 20 person in whom there is ascertainable any Negro blood shall be deemed a colored person.”44 One study of eugenics reveals some interesting details that may potentially have happened in Vermont. This study followed 270 patients who had been sterilized in Elwyn, Pennsylvania. Since Pennsylvania had never enacted a law permitting sterilization, this suggests that the actual number of sterilizations carried out in the United States were significantly larger than the numbers allowed under state law.45 The Surgical Solution puts forth the following conclusions about the sterilization movement in the United States: 1. More than 60,000 people were sterilized under the laws 2. Programs were most active during the 1930’s, but in some states they were also active in the 1940’s and 1950’s 3. During the Depression there was a major change in the factors that most concerned the officials who had the power to sterilizeless concerned with preventing the birth of children with genetic defects and more concerned with preventing the parenthood in those individuals who were thought to be unable to care for children- this resulted in a dramatic change of who was to be sterilized 4. Beginning in 1930, there was a steady rise in the percentage of young women who were sterilized 5. Germany’s sterilization programs did not have a negative affect on those in America- instead advocates pointed to Germany to illustrate how a good program could reach its goals 6. There was a sharp decline in the number of people sterilized in the 1940’s in the United States, but this was due to the war and the shortage of civilian physicians.46 Sterilization may not be one of America’s proudest policies, but it did occur throughout the nation, and it had lasting effects on the generations to come. 44 Reilly, 74. Reilly, 90. 46 Reilly, 94-95. 45 21 The early sterilization efforts were focused on men. This had to do with the fact that men made up the vast majorities of people in jails, and convicts were deemed to be the problem. At the same time, vasectomies were much easier to perform than hysterectomies.47 At the end of 1927, 53% of all persons legally sterilized in the United States were male. Then from 1932 to 1934, sterilizations were performed on 4,258 women (60%) and 2,842 men (40%).48 The gender balance had switched, but the reasons for that switch remain unknown. Petition for Recognition If the Abenaki claims are true, their history, present, and future, have been largely impacted by the Vermont Eugenics Survey. This discussion has been brought to the forefront because of the desire of the Abenaki to gain federal recognition as an American Indian Tribe. Through this process, an exhaustive search was done for materials that related to the Abenaki, and thus the discussion of the Vermont Eugenics Survey and its effects on the Native American population of Vermont. In the 1982 petition for Federal Recognition as an American Indian Tribe, the Abenaki write that they have been discriminated against for centuries, and the Vermont Eugenics Survey only made things worse. They write that this discrimination resulted in the Abenaki hiding their heritage, and how this has hurt Abenaki society over time. “It is also clear that Indians eventually came to feel unwanted and unliked by local whites, with the result that they often concealed 47 48 Reilly, 34. Reilly, 98. 22 their identity…There is no doubt that “Indian” had become a degraded status.”49 Apparently, this was not just the case in Vermont, but prevalent around the country. The Abenaki repeat their message by saying: “As in many Indian communities nationwide, the negative stereotyping so prevalent among the local white community gradually became a part of Abenaki self-identity as well, reinforcing feelings of resentment and despair.”50 A picture is painted of a people who have been pushed to the fringes of society and have suffered greatly due to the stereotypes and cruelty of their neighbors. This is most likely true, but what comes into question is how the Eugenics movement added to (or didn’t add to) the growing dislike towards “others” in Vermont. The Abenaki petition for Federal Recognition obviously takes a very proAbenaki position since it was written for the Abenaki. Before you look at the other side of the argument, it helps to get the full spectrum of the arguments the Abenaki presented for discrimination and the Eugenics Survey. The petition reported that they believed that the discrimination that they had endured could have prevented parents from passing on their knowledge and traditions to younger generations.51 This implies that this would effectively end the Abenaki civilization over time, because there would be a lack of tribal members with any knowledge of their history. In addition to sharing their knowledge with their own kin, the Abenaki suggest that they had no desire to share their culture with the rest of Vermont and the primary reason for this decision was the pain caused by the Eugenics Movement. “Any desire of the Abenaki people…was brutally 49 Abenaki Nation of Vermont, 98. Abenaki Nation of Vermont, 99. 51 Abenaki Nation of Vermont, 99-100. 50 23 shattered by the infamous Eugenics Movement that took hold in Vermont… and its ethnic cleansing and sterilization of ‘undesirables.’”52 This is used as further proof of why the Abenakis have had a decreased presence in Vermont since the in the 1920’s and 1930’s. Other researchers and historians have agreed with the theory that the Abenaki were targeted by the eugenics survey. This idea gained significant publicity after it appeared in a 1999 Boston Globe article written by Ellen Barry. She says: And among the more angry of the Abenaki, sterilization simply seems like another aspect of a multi-faceted campaign to destroy them. Homer St. Francis, a longtime chief of the Abenaki, reels of the names of childless family members who he assumes were sterilized. He sees sterilization as part of a larger government conspiracy to eliminate his family- a campaign that he said includes generations of abduction and outright murder.53 This is a very strong view and a potentially convincing one. Kevin Dann reminds his readers that the Eugenics Survey investigated “gypsy” and “pirate” families, which it did. He then suggests that those families were actually Abenaki Indians,54 and that this is just another example of how they were targeted. Nancy Gallagher, the author of Breeding Better Vermonters: The Eugenics Project in the Green Mountain State, seconds his position by saying: “Recent research by the Abenaki people has revealed that Perkins and Abbott’s Gypsy family were indeed Abenaki families…”55 The important phrase in that sentence is that the Abenaki Nation of Vermont: Second Addendum…, 4. Ellen Barry, “Eugenics Victims Heard at Last,” Boston Globe, <http://www.geocities.com/bigorrin/archive4.htm> (15 July 2006). 54 Kevin Dann, “From Degeneration to Regeneration: The Eugenics Survey of Vermont: 19251936,” Vermont History 59 (1999): 14. 55 Nancy L Gallagher, Breeding Better Vermonters: The Eugenics Project in the Green Mountain State (Hanover: University Press of New England, 1999), 81. 52 53 24 Abenaki people have uncovered this information. In order to stay purely objective, an outsider with no stake in the research would need to concur before a direct connection is made. In 1951, a report was released by the American Journal of Mental Deficiency that estimated that 210 peopled had been sterilized in Vermont. When asked about this, Perkins, the head of the Eugenics Survey, responded that many more people had actually been sterilized.56 The majority of those sterilized were women, and by 1936, sixty-five women had been sterilized in Vermont compared to thirty-two men.57 What remains unknown is if any of these victims were Abenaki, and if yes, how this has affected the Abenaki communities population counts. Nancy Gallagher explains this glitch: The Eugenics Survey archive does not document sterilizations resulting from the law…Because legal sterilizations took place for the most part in institutional settings, the identities of persons sterilized under the law remain hidden in confidential case files of the Department of Public Welfare.58 Much is still unknown about this topic, but the Abenaki were convinced that they were significantly wronged by the state of Vermont and the Eugenics Survey. In fact, they believe that Vermont had its reputation blemished by its participation in the movement, since the state government “embraced the doctrine of the ‘inferior race’ under the guise of voluntary sterilization.”59 From this, the Abenakis have incorporated the Eugenics Survey into their fight for federal recognition. 56 Dann, 29. Dann, 13. 58 Gallagher, 124-125. 59 Abenaki Nation of Vermont, Second Addendum…, 9. 57 25 The movement for federal Abenaki recognition began in the early 1970s. At this point in time, Abenakis began to gather and hold meetings on a more regular basis. This was partly a result of the American Indian Movement which gained popularity and support in the 1970s. Several Abenakis began to think more about their status as Indians and what could be done to improve their status and way of life.60 By 1975, The Abenaki had established a Tribal headquarters in Swanton, Vermont (which now includes a Tribal Museum and a cultural center) and began to formally organize membership in the tribe. At the end of 1975, they had a membership of 375 people. To become a member at this time, you had to be a member of one of the recognized Abenaki families, or be close to a council member. You were given a card that identified you as a member of the St. Francis/ Sokoki band of the Abenaki Nation of Vermont, and membership was based upon the personal knowledge of individual Abenaki families.61 To the Abenaki, the “purity” of the Abenaki was not the real issue, instead the central point was that they were a community of people who recognized themselves as Indian and had decided to act out on that identity. 62 The state of Vermont has a slightly different perspective of the events leading up to the Abenakis decision to apply for recognition. They state that “There is very little to say about the Abenakis in Vermont in the twentieth century until the 1970’s. From 1900 to 1974 they were invisible, if they were here at all…There was no noticeable Abenaki community in Vermont, let alone Franklin 60 Abenaki Nation of Vermont, 104. Abenaki Nation of Vermont, 106. 62 Abenaki Nation of Vermont, 113. 61 26 county, from 1900 to 1970.”63 The state’s position is also that it was only because of the increase in ethnic consciousness around the United States, that the Abenakis became detectable and came together once again. One of the criteria for federal recognition is that “the petitioner has maintained political influence or authority over its members as an autonomous entity from historical times until the present64, and the state believes that the Abenaki do not meet this requirement. Using the Vermont Eugenics Survey as a Tool to Achieve Federal Recognition While the Abenaki people contend that the Vermont Eugenics Survey had a profound effect on their tribe, both the state of Vermont and the Bureau of Indian Affairs question this connection. The state of Vermont notes the Second Addendum to the Petition for federal recognition, which was filed in 1995, lists one of the Abenakis’ sources as the Vermont Eugenics Survey. The Second Addendum describes the Vermont Eugenics Survey as a discriminatory program that was aimed at the eradication of mental and moral defectives in the Vermont community.65 The Abenaki’s petition briefly mentions the notion that Indians were targeted by the survey, but this idea has become a substantial argument as to why the Abenaki feel that they should be granted federal recognition. The first published connection between the Vermont Eugenics Survey and Abenakis comes from Kevin Dann’s 1991 article in Vermont History: “From Degeneration to Regeneration: The Eugenics Survey of Vermont, 1925-1936.” In 63 Sorrell, 67. Cason, 91. 65 Sorrell, 68. 64 27 this article Dann writes that the “gypsy” and “pirate” families that were studied under the Eugenics Survey were of Abenaki and French-Canadian ancestry.66 When this was brought to the attention of the state, it was noticed that citations were not provided for the source of Dann’s information. Nor did he suggest that the Abenakis needed to conceal their identities because of the Eugenics Survey, or that they were one of the primary targets of the survey. Dann’s information was used by other historians, including Nancy Gallagher. Her comprehensive history of the Vermont Eugenics Survey did not verify a eugenic focus on Abenaki families and in fact, her only references to Abenaki subjects are based on the ideas presented by Dann.67 The next time the connection between the Abenaki and Eugenics Survey was espoused was in the late 1990’s when it became a part of a history kit published by the Vermont Historical Society. This history kit claimed that: From the 1920’s through the 1940’s the Eugenics Survey of Vermont…sought to “improve” Vermont by seeking out “genetically inferior peoples” such as Indians, illiterates, thieves, the insane, paupers, alcoholics, those with harelips, etc…As a result of this program, Abenaki had to hide their heritage even more. They were forced to deny their culture to their children and grandchildren.68 It is likely that the Abenaki Indians would have felt threatened by the Vermont Eugenics Survey, but there is no proof that they were systematically targeted. This piece of evidence shows how information can be used to convince the audience of a fact, without presenting proof for that argument. 66 Sorrell, 74. Sorrell, 75. 68 Ibid., 69. 67 28 Over the next several years, the connection between the Abenakis hidden heritage and the Eugenics Survey continued to be discussed in public venues. One newspaper article that reported the death of Chief Homer St. Francis said that St. Francis’s tribe had been “driven underground by racism. That racism found its purest expression in the ‘eugenics’ campaign of the 1920’s and 30’s, which promoted the sterilization of Abenaki and other groups of Vermont’s ‘undesirables.’”69 By placing such information in the newspaper it ensured that public sympathy would be garnered, even if there was no proof of that information actually existing. What makes this sudden connection more interesting is that neither the original petition for federal acknowledgement, which was filed in 1982, nor the first Addendum to the Petition filed in 1986, contained any mention of the Vermont Eugenics Survey. If the Vermont Eugenics Survey had such a significant impact on the Abenaki people that it forced them to go underground with their culture and heritage, it can be argued that they would have used this information as a primary source in their first petition, but they did not. The first mention of the Eugenics Survey is the Second Addendum, from 1995, where it is referred to, but there are no arguments on its effects of the invisibility of Abenaki families and individuals.70 The State of Vermont instead argues that there is nothing in the Eugenics Survey papers that indicate that the Abenakis were targeted. Instead, they believe that if one group was targeted, it was the French Canadians. They do 69 70 Ibid., 70. Sorrell, 70. 29 agree with the fact that some persons of Indian descent were included in the survey, and in particular there were two families who intertwined with others of Indian descent. On the other hand, there is no proof in the survey that those people were Abenaki Indians.71 Fred Wiseman believes that Indians were described in the survey as gypsies or basketmakers instead of being referred to as Indians. He contends that this was because the people conducting the survey did not know they were Indians because they were so good at hiding their true identities. From this, the state of Vermont argues that it is hard to believe that Henry Perkins would have been blind to the presence of Indians in Swanton and the surrounding areas, particularly if these were the people that he aimed to study in the Eugenics Survey.72 One of the state of Vermont’s strongest arguments against the use of the Eugenics Survey in relation to Abenaki recognition lies with World War I draft registration cards. These documents indicate a lack of self-identification with any Indian tribe, including the Abenaki. Members of the Lampman and St. Francis families indicated their race to be white or Caucasian on their draft registration cards. The Lampman and St. Francis families have strongly advocated their Abenaki heritage throughout history and have been leaders in the fight for recognition, so it makes it interesting that they did not self-identify on those cards. What the state of Vermont finds interesting about these cards is that they pre-date the Vermont eugenics movement by several years. In this case, any argument that the petitioner’s ancestors tried to hide their Indian identities 71 72 Sorrell, 242. Sorrell, 77. 30 because they feared the repercussions of the Vermont Eugenics Survey is incorrect. The survey had not yet started, so there is no reason at that point in time for the Abenaki individuals to be afraid of self-identifying themselves as Indian, rather than white or Caucasian.73 When the state of Vermont came to the conclusion that there was no connection between the Eugenics Survey and the Abenaki Indians, they wondered why the Abenaki had made the connection in the first place. Their first reason is that the Eugenics Survey has been used as a tool to try to explain why the Abenaki have had no presence in history since the American Revolution. If they had felt threatened, this could potentially explain why they went underground. The state also believes that the Abenaki used the Eugenics Survey to their benefit in the following ways: 1. By using such a disagreeable subject as ethnic cleansing to excuse their lack of documentation as a tribe. 2. By eliciting sympathy from Vermonters who were no doubt ashamed of their state’s participation in the Survey. 3. By swaying public opinion towards allowing less documented facts and more insinuation. 4. By influencing historians and others writing about them to include undocumented suppositions on the grounds that the Eugenics Survey had made real evidence scarce.74 From these conclusions, it is fair to say that the state of Vermont’s official position is that the Abenaki Indians have used or created a connection to the Vermont Eugenics Survey that paints them in a favorable light and helps to advance their own motives. The Abenaki would undeniable argue that this was not the case, but because they were reluctant to participate in this research effort, their position cannot be clearly stated. 73 74 Sorrell, 192. Sorrell, 242. 31 The Eugenics Survey in regards to the Bureau of Indian Affairs Decision on Recognition When the Bureau of Indian Affairs published its findings on the Abenaki Indians, it decided that the Abenaki were missing several criteria that they were required to have to become a recognized tribe. Several of these areas of concern included references and information about the Eugenics Survey. Criterion 83.7 (b) requires that: “a predominant portion of the petitioning group comprises a distinct community and has existed as a community from historical times until the present.”75 The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) found that the Abenaki tribe did not meet this requirement, which requires that the group must have regular social interactions among members of the community and be a community that is distinct from other communities in the area. In the petition for recognition, the Abenakis claimed that the Vermont Eugenics Survey was directly responsible for the group’s reluctance to identify themselves as Indians at that time. No evidence was presented that showed that the petitioner’s ancestors knew about the Eugenics Survey or were affected by the actions of the survey. The BIA admits that people might be reluctant to talk if they had been sterilized involuntarily, but there is only one example of a group member who told the story of how she believes her aunts were sterilized: “Actually, in my family two of my aunts were sterilized. They were picked up, and brought to the State Hospital, in the state of Vermont, drugged up, sterilized without their knowledge…”76 This may be true, but there is no evidence that 75 76 Cason, 44. Cason, 79. 32 shows that these women were targeted for a specific reason, such as Abenaki or Indian heritage. The Abenaki also argued that it was because of the Eugenics Survey that they did not have a completed tribal membership list. As stated earlier in this paper, when the group formally organized in the 1970’s, they began to keep track of their members. Prior to this, they never maintained a list because everyone in the community knew each other, which rendered a membership list unnecessary. When a list was compiled, the membership criteria was very open, and in 1982 they claimed to have a membership of 935 adults and 750 children under the age of fifteen, for a total of 1,685 members.77 The other portion of the petition that the Abenaki failed to meet that relates to the Eugenics Survey was Criterion 83.7 (a). This requires that: “the petitioner has been identified as an American Indian entity on a substantially continuous basis since 1900.”78 The BIA stated that sources have identified the group as American Indian only since 1976, and the census records provided does not provide tribal affiliations or specific Indian entities, so there is no way to show that those registered as Indians were actually Abenaki. The Vermont Eugenics Survey is referenced because the Abenaki suggested that some of their Indian ancestors may have been identified in the papers. The BIA ultimately concluded that nothing in the Eugenics papers demonstrates that the Vermont Eugenics Survey identified or dealt with an Indian entity.79 Vermont’s Assistant Attorney General Eve Jacobs Carnahan agreed with this assessment. She believes that 77 Ibid, 87-88. Ibid, 22. 79 Ibid, 26. 78 33 there are individuals in Vermont with Native American heritage, but there is a lack of evidence linking those people to the tribes of long ago.80 Conclusions The Abenaki Indians of Vermont could very well have been targeted by the Eugenics Survey, but the evidence to support that claim is not currently available. Yes, it is probable that some Abenaki individuals were sterilized because of the Vermont Eugenics Movement, but it may have been for other factors, such as mental illness, alcoholism, or having children out of wedlock. By no means is this is a conclusive document on the topic, and with the cooperation of the Abenaki Indians, a lot more could be learned about this subject. However, the information that is available is fairly convincing that, no, the Abenaki Indians were not targeted by the Eugenics Survey, which negates their use of the survey in their arguments for recognition. The issue itself is complex and sensitive, making it difficult to research and making individuals reluctant to get involved in a project devoted to exploring it further. This is in no way intended to detract from the Abenakis claims that they were hurt by the Eugenics movement; without knowing their side of the history it is impossible to make that judgment call. What can be said is that the evidence proving that they were affected is not available to the public, so until some documentary evidence is presented, this history mystery will remain unsolved for the time being. Even if the Abenaki Indians were affected by the Eugenics Survey, they have achieved great things over the last several decades. The steps that have 80 Nancy Remsen, “Abenaki Plead for recognition,” Burlington Free Press, 16 February 2005, sec. B. 34 been taken to unite the community, organize the community, and petition for recognition several times have taken enormous amounts of effort and dedication. The Abenaki deserve to be acknowledged by the state of Vermont without even taking the Eugenics Survey into consideration. 35 Bibliography Abenaki Nation of Vermont. “A Petition for Federal Recognition as an American Indian Tribe.” Submitted to the Bureau of Indian Affairs. October 1982. Abenaki Nation of Vermont. “Second Addendum to the Petition for Federal Recognition as an American Indian Tribe: Genealogy of the Abenaki Nation of Missiquoi.” 11 December 1995. Barry, Ellen. “Eugenics Victims Heard at Last.” Boston Globe. <http://www.geocities.com/bigorrin/archive4.htm> (15 July 2006). Cason, James E. “Summary under the Criteria for the Proposed Finding on the St. Francis/ Sokoki Band of Abenakis of Vermont. “ 9 November 2005. Chalk, Frank and Kurt Jonassohn. The History and Sociology of Genocide. London: Yale University Press, 1990. Corkery, Michael. “Abenaki doubt Census Numbers.” Burlington Free Press. 15 September 1999. Sec. A. Cowperthwait, Richard. “Abenaki Count Stressed: Panel vies for accuracy in Census.” Burlington Free Press. 24 September 1999. Sec. B. Dann, Kevin. "From Degeneration to Regeneration: The Eugenics Survey of Vermont: 1925- 1936." Vermont History 59 no.1 (Winter,1991): 5-29. Decher, Laura. “Figures show Indians have toughest route in VT.” Burlington Free Press. 7 July 1991. Sec. A. Gallagher, Nancy L. Breeding Better Vermonters: The Eugenics Project in the Green Mountain State. Hanover: University Press of New England, 1999. Haviland, William A. The Original Vermonters: Native Inhabitants, Past and Present. Hanover, New Hampshire: University Press of New England, 1994. Reilly, Philip. The Surgical Solution: A History of Involuntary Sterilization in the United States. London: The John Hopkins University Press, 1991. Remsen, Nancy. “Abenaki Plead for recognition.” Burlington Free Press. 16 February 2005. Sec. B. Ryan, W Carson Jr. “Special Capacities of American Indians.” In the Vermont Eugenics Survey files. 36 Sorrell, William H., and Eve Jacobs-Carnahan. “State of Vermont’s Response to Petition for Federal Acknowledgment of the St. Francis/ Sokoki Band of the Abenaki Nation of Vermont.” 2002. University of Vermont. “The Eugenics Survey of Vermont 1925-1936: An Overview. Vermont Eugenics: A Documentary History. 2001. <http://www.uvm.edu/~eugenics/overview.html> (31 May 2006). University of Vermont. “Family Studies of the Rural Poor: 1925-1928.“ Vermont Eugenics: A Documentary History. 2001. <http://www.uvm.edu/~eugenics/famstudies.html> (1 June 2006). University of Vermont. “1925-1928: The Search for “Bad Heredity” in Vermont: “Pedigrees of Prejudice”. Vermont Eugenics: A Documentary History. 2001. <http://www.uvm.edu/~eugenics/overview1.html> (31 May 2006). Wiseman, Frederick Matthew. The Voice of the Dawn: An Autohistory of the Abenaki Nation. Hanover: University Press of New England, 2001. 37 The Number of Native Americans Residing in the State of Vermont Determined by the Federal Census Bureau 2600 2500 2,420 2400 2300 2200 2100 2000 1900 1800 1,696 1700 Number of Native Americans 1600 1500 1400 1300 1200 1100 984 1000 900 800 700 600 500 400 300 229 200 100 10 26 24 36 1900 1910 1920 1930 16 30 1940 1950 57 0 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Year 38 Ad di so n Be C nn ou in nt gt y on C C al ou ed nt on y ia C C hi ou tte nt nd y en C o un Es ty se x C o Fr un an ty kl in G C ra ou nd nt y Is le C La ou m nt oi y ll e C ou O ra nt ng y e C ou O rl e nt y an s C o R un ut ty la n W d as C ou hi ng nt y to n C W o in un dh ty am C W ou in nt ds y or C ou nt y Number of Native Americans 100 93 200 74 hi tt ni a de n do en al e to n on C ou nt y nt y ou ou C C Es nt y Co u nt se y Fr x C ou an nt kli G y n ra C nd ou nt Is La l e C y m ou oi nt lle y C O ou ra nt ng y e O C rle ou an nt y s C R ou ut la W nd nty as Co hi ng t o unt y W n Co in dh u nt am y W C in o u ds nt or y C ou nt y C C ng di s nn i Ad Be Number of Native Americans Number of Native Americans Living in Vermont in 1900 By County 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Series1 County Name Number of Native Americans Living in Vermont in 2000 by County 800 700 684 600 500 400 403 300 163 172 104 41 60 76 144 175 97 134 0 County Nam e 39 Native Americans Residing in the Three Vermont Counties That Are Historically Recognized As Having Been the Homelands of the Abenaki Indians 750 684 700 650 584 Number of Native Americans 600 550 1900 500 1910 450 1920 422 403 1930 400 1960 350 1970 286 300 1980 1990 250 2000 200 156 150 100 50 60 46 0 9 4 6 9 0 5 0 3 1 9 0 0 0 0 0 1 25 23 0 Chittenden County Franklin County Grand Isle County County Name 40