darwin.doc

advertisement

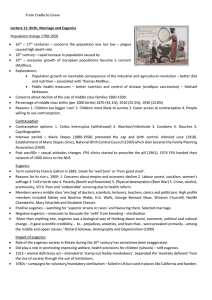

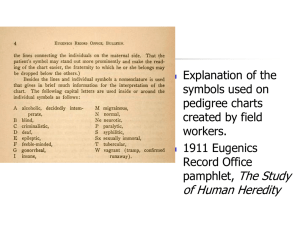

In the Name of Darwin by Daniel Kevles Some supporters of Darwin's theory of evolution have misapplied the biological principles of natural selection -- "survival of the fittest" -- to the social, political, and economic realms. The idea of "social Darwinism" originated in the class stratification of England, and has often been used as a general term for any evolutionary argument about the biological basis of human differences. Drawing on social Darwinism, supporters of the 20th-century eugenics movement sought to "improve" human genetic stock, much as farmers do in agriculture. This essay examines the history of eugenics and considers modern genetic research in the same light, so that the lessons of history are not forgotten. The specter of eugenics hovers over virtually all contemporary developments in human genetics. Eugenics was rooted in the social Darwinism of the late 19th century, a period in which notions of fitness, competition, and biological rationalizations of inequality were popular. At the time, a growing number of theorists introduced Darwinian analogies of "survival of the fittest" into social argument. Many social Darwinists insisted that biology was destiny, at least for the unfit, and that a broad spectrum of socially deleterious traits, ranging from "pauperism" to mental illness, resulted from heredity. The word "eugenics" was coined in 1883 by the English scientist Francis Galton, a cousin of Charles Darwin, to promote the ideal of perfecting the human race by, as he put it, getting rid of its "undesirables" while multiplying its "desirables" -- that is, by encouraging the procreation of the social Darwinian fit and discouraging that of the unfit. In Galton's day, the science of genetics was not yet understood. Nevertheless, Darwin's theory of evolution taught that species did change as a result of natural selection, and it was well known that by artificial selection a farmer could obtain permanent breeds of plants and animals strong in particular characteristics. Galton wondered, "Could not the race of men be similarly improved?" Daniel J. Kevles, a historian of science and society, is the Stanley Woodward Professor of History at Yale University. He has written extensively about the social and political relations of science. His works include In the Name of Eugenics (1995), The Physicists: The History of a Scientific Community in Modern America (1995), and The Baltimore Case: A Trial of Politics, Science, and Character (2000).