The Flapper: The Heroine or Antagonist of the 1920s

advertisement

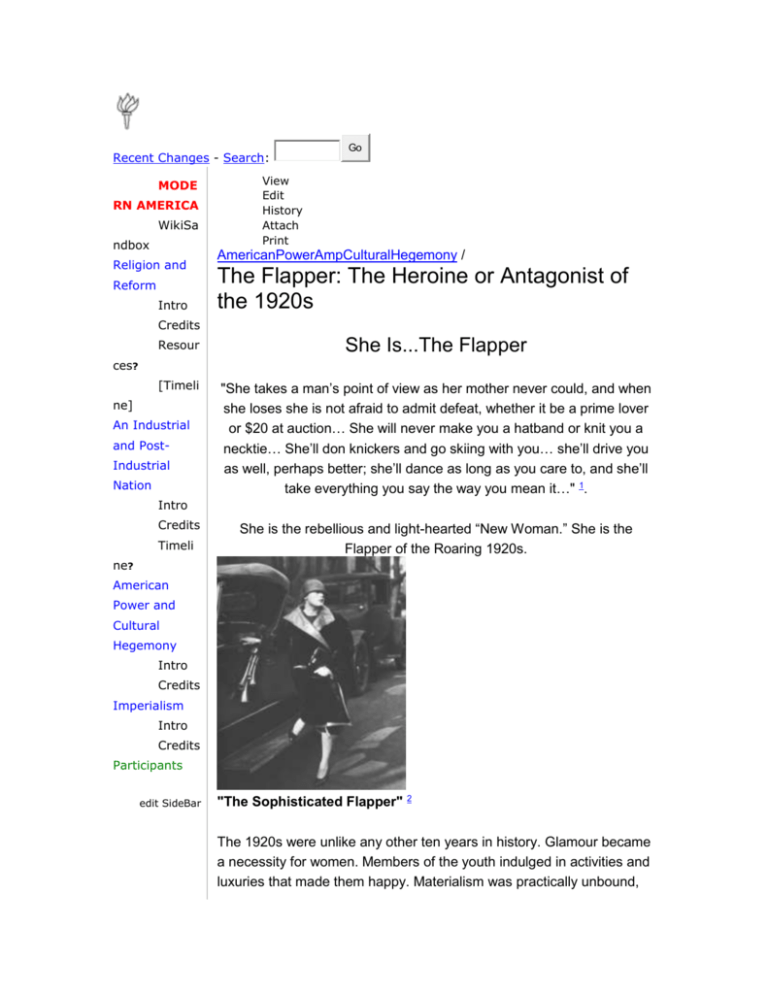

Recent Changes - Search: MODE RN AMERICA WikiSa ndbox Religion and Reform Go View Edit History Attach Print AmericanPowerAmpCulturalHegemony / The Flapper: The Heroine or Antagonist of the 1920s Intro Credits Resour She Is...The Flapper [Timeli "She takes a man’s point of view as her mother never could, and when she loses she is not afraid to admit defeat, whether it be a prime lover or $20 at auction… She will never make you a hatband or knit you a necktie… She’ll don knickers and go skiing with you… she’ll drive you as well, perhaps better; she’ll dance as long as you care to, and she’ll take everything you say the way you mean it…" 1. ces? ne] An Industrial and PostIndustrial Nation Intro Credits Timeli She is the rebellious and light-hearted “New Woman.” She is the Flapper of the Roaring 1920s. ne? American Power and Cultural Hegemony Intro Credits Imperialism Intro Credits Participants edit SideBar "The Sophisticated Flapper" 2 The 1920s were unlike any other ten years in history. Glamour became a necessity for women. Members of the youth indulged in activities and luxuries that made them happy. Materialism was practically unbound, “scandalous” dancing was more than just a pastime, and ideals and morals greatly shifted. From 1920 to 1929, America experienced a period of great change, both socially and economically. Whether one blames World War I, women’s suffrage, music, or prohibition, a new rebellious youth, especially “new women,” emerged and impacted future generations. These youthful women became known as Flappers, and were recognized for their bold actions, their daring and self-reliant character, their scandalous attire, and more than anything their desire for equality with their male counterparts. Though the Flapper lifestyle clearly did not last forever, the changes in women’s attitudes, ideals, and actions (as they contradicted the morals of previous generations), left a profound impact on women to be independent and un-submissive to men. The Flapper generated both a new emotional culture for women of vast ages and races, as well as a new youth identity for her and her beau. The Development of The Flapper Era World War I undoubtedly played a great role in the development of the Flapper. However, research on Greenwich Village attire shows that "inherent changes in morals and manners expressed through appearance existed among single working-class and middleclass women in urban areas even earlier than WWI" 3. This particular movement was sparked by New York's Bohemian women- those artsy actresses and members of the 1910s literary culture who "experimented with dress in a highly politicized and culturally artistic environment permeated with feminist, socialist, and Freudian ideas" 3. The mini-counterculture began its growth far before the Flapper icon emerged; however, the strain of the war added to the liberal beliefs already forming. The Flappers and their boyfriends grew up during World War I, surrounded by devastation, as families and prosperity fell apart. Perhaps the drinking, smoking, and dancing, characteristic of the youth, were means to escape the pain. The youth claimed, “We have been forced to live in an atmosphere of ‘to-morrow we die,’ and so, naturally we drank and were merry…” 4. During the war, families had to give up many of their luxury items and favorite activities, and young children even joined the workforce for extra family income. WWI forced austerity and sacrifice upon Americans, and the Flapper was simply the result 5. She wanted to enjoy being alive and embrace the temporarily war-free society. While the men served in the United States military, women split their household duties with jobs outside the home. Before the war, and oftentimes after, men were viewed as the breadwinners while women stayed home tending to the house and the children. Women who held jobs often quit upon marriage and proceeded to rely on their husbands’ income. However, after the war many women desired to remain in the workforce. The Flapper “…demanded the same social freedom for herself that men enjoyed. Consequently she left home and asserted herself in the business world” 6. In fact, “by 1930, 10.8 million women held paying jobs, an increase of 2 million since [the] war’s end” 7. With the boys back in the country, these women often held jobs that men were rarely interested in, so the sexes continued to be separated in the workplace. Nonetheless, women enjoyed the money and the purchasing power that enabled them to buy the many new labor-saving devices that were manufactured after the war: washing machines, irons, and vacuums. As both the gross national product and salaries increased in the twenties, such items were available to more than just the wealthy in American society 7. The time that women saved using the new appliances was used not only to go out to the Flapper’s favorite jazz club or speakeasy but also to work more hours and earn yet more money. This money enabled the working Flapper to purchase the ultimate ticket to independence: the automobile. The Flapper & The Ford 8 As Ford mass-produced cars via the assembly line and gained competition, automobiles became more affordable to even the newly working young women. Not only did the automobile allow the Flapper to go wherever men could and to share in all their enjoyments, but it also spawned what would become a great shift in traditional courtship and dating. “In other days the boy paid court to his ‘girl’ on an ivied porch or in a cosy parlor, under the watchful eyes of a mother or the stricter vigil of a maiden aunt” 4. In the twenties, however, couples drove away from home, “indecently” as the parents believed. “By 1927 more autos were enclosed… creating new private space for courtship and sex” 7. This more intimate setting combined with the close dancing habits of the Flapper altered women’s perspective on, and openness to, sexual behavior. Voting, and Drinking, and Smoking, Oh My! The Shocking Activities, Fads, and Scandals of The New Woman "Standing Out In The Crowd" 9 In addition to having the mobility necessary for independence, early Flappers were also among the first to vote along side American males. In 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified and after all the suffragist campaigns women were finally given the right to vote. “Some blamed the vote for young women’s excessive behavior: ‘Political and economic liberty… has come to women, who, retaining their sex instincts and yet not knowing how to use their freedom, are apt to claim the virtues and ape the vices of men’” 4. They were given a privilege that their mothers never were during their youthful years, already giving Flappers inspiration that they could be equal with men. Just six months before the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified, the Eighteenth Amendment referred to as the Volstead Act was approved after reform-seeking women pressured Congress to prohibit the alcohol that was “ruining society.” These Victorian reformers hoped to eliminate prostitution and the saloon, while raising men’s principles. One of their demands was this described prohibition of alcohol. However, after the war, the new woman began concentrating on herself more than others, and her thoughts on alcohol consumption (among many activities) drastically altered, perhaps, as mentioned, as a means to forget the sufferings of the war 6. Regardless of the fact that Flappers’ thoughts on alcohol contrasted with those of their mothers, the Volstead Act was indeed enacted. For the next thirteen years, the manufacture, sale and possession of alcohol were prohibited 10. But America was not as “dry” as the law describes it to have been. Many Americans treated the Volstead Act as a joke; it was constantly violated without concern. The Volstead Act was broken more than any other law by “…so many ‘decent lawabiding’ people” 10. Equality-seeking Flappers and their boyfriends drank liquor constantly in clubs and speakeasies. Mothers and grandmothers were shocked that their these girls were drinking in public, let alone drinking against the law. Not only did the Flapper drink hard liquor, but she also took to smoking. It was not uncommon in the twenties to walk into a loud jazz club and see a young Flapper dancing barely clothed with a cigarette in one hand a glass of alcohol in the other. The Flapper had indeed “‘established the feminine right to equal representation in such hitherto masculine fields of endeavor as smoking and drinking…’” 5. Flappers could almost never settle for an activity being only a “masculine field”; she wanted equality and fought for more unisex activities. The habit of female smoking, however, seems to have been lees of a result of seeking equality with men and more of a result of stress from war. However, once the habit began, smoking in public and cigarette choices were certainly moves to show that women would not be dominated by their elders nor categorized below men. “A decade or so before, a President’s daughter, Alice Roosevelt, was asked to leave the lobby of a Chicago Hotel after she had lit a cigarette” 11. However, during the war, the cigarette was used by both men and women as a sedative and was considered more than just a small reason that smoking spread to young women 11. Women in the twenties bought cigarettes, or “coffin nails,” as the older generation preferred to call them, just as often as men, and also chose to smoke the same brand of potent cigarettes as men. The older generation believed that with the war being over there was no reason to continue this crude and, as the nickname alludes to, hazardous habit. Still, smoking continued and became a major symbol of the rebellious Flapper. What Would Her Mother Think? The Flappers Defy The Norms of The Older Generations The older generation disapproved of the crude habits Flappers adopted and even flaunted. Flappers were energetic, but their parents believed that their energy was focused in the wrong direction. They focused on, as a female member of the older generation stated, “‘a frivolous pursuit of fun rather than trying to better their sex and their race’” 4. Victorian mothers and grandmothers frowned upon the youth’s reckless and carefree attitudes. The young women, however, were still dealing with returning to normalcy after the war, and, instead of helping the youth control their need to move through reckless behavior, the elders scorned the youth and gave them more reason to rebel against those that wanted to control them. One Flapper reached out to the older generation saying, “You must help us…The war tore our spiritual foundations and challenged our faith. We are struggling to regain our equilibrium” 12. Behind those heavily-made up faces were young girls who wanted advice and guidance, instead of scorn and criticism 12. The great distrust the older generation had for the youth created a large barrier and generation gap within society. “Youth culture that had existed on a smaller scale before the war now became a major social phenomenon separating college students from adults” 13. The waraffected youth stuck together in disagreeing with, and acting out against, their parents' beliefs on what was proper and acceptable. The nation’s view of the youth shifted to shock over the rebellious attempts at gaining gender equality. More than ever, adults realized the age gap between themselves and their children. Although, certainly not all teenage girls were Flappers, the Flapper became a major symbol in the 1920s cultural view of a new radical youth. Thus, although not in numbers, the Flapper indeed shook the (partially) global youth. This, of course, will be seen again in the United States when the age gap of the 1950s and 1960s creates the countercultural of the 1960s protests. The Flapper’s new sense of fashion and leisure, as we will soon see, influenced her views of sexuality and transcended through American middle-class society to form a new emotional and even social culture for women. One cannot simply blame the older generation for criticizing the “flaming” youth. Flappers grew up with many more opportunities that their mothers were still grasping. One Flapper, embracing her new found freedom stated, “I can think & act; perceive & execute, reason & react in a thousand different ways that my grandmother & even my mother never could” 14. The parents and grandparents indeed criticized their children and grandchildren who carried on such astoundingly different lives than they had, but they slowly began to accept their daughters coming home drunk and going out to petting parties. The mothers would soon even join in the new female social culture of openly accepting sexuality and smoking. In the early to mid-twenties, however, the Victorians remained aghast. Among many Flapper habits that the older generation disapproved of, Flapper slang became well known and mocked by mothers. Flapperdom was the first youth movement that adopted it own slang dictionaries, and “The Flapper magazine predicted without hesitation that ‘many of the phrases now employed by members of this order [the Flapper movement] will eventually find a way into common usage and be accepted as good English just like many American slang words’” 5. Although many of the slang words such as “fire alarm” (a divorced woman) and “blue serge” (a sweetheart) did not last much longer than the Flapper movement, other words remain but with the same, or altered, meanings. The terms “big timer” and “bimbo” are still used in the 21st Century, but not to refer to a “charming and romantic man” or “a great person” respectively. There are, however, certain terms that have made a lasting impression on society and originated with the Flappers. Such terms include “ab-so-lute-ly,” “and how!,” “big cheese,” “heebie-jeebies,” "killjoy,” and "pos-i-tive-ly” just to name a few. Though mothers were stunned by the slang, the terms were mostly innocent and united the youth culture. These words remain today as catchy sayings that maintain the spunk of the late Flappers 5. She's Wearing What? Flapper Dress and The Will to Let Loose "Fashions from Autumn of 1928" 15 “A vivid image of the Flapper is firmly fixed in our collective cultural memory-the shocking and wild, bootleg-gin-drinking, cigarette-inholder-smoking, necking and swearing, Charleston-dancing jazz baby; the short-haired or bobbed-hair young girl with a defiantly boyish figure, a fringed skirt, and stockings rolled and bunched below the knee as brazen witness to the fact that-gasp-she wore no corset” 5. Flappers were young, working women who went to the jazz club after work or perhaps after school, depending on her age; she did not have the time nor the desire to be held back by a highly restrictive corset, as her mother and grandmother most likely wore their entire lives. Women’s attire showed major alterations as early as the 1910s, through Bohemian dress common in New York City’s Greenwich Village. The bohemian feminists intensity was obvious not only in her extreme beliefs regarding sex and marriage, but also in her desire to dress in less restricting clothing. This “feminist dress” was evident by 1914, when females began “bobbing” their hair and dancing at youthful halls such as the Village’s Liberal Club in “calf-length skirts and jumpers, tunic tops, and low sandal-type shoes” 3. Such attire already posed a threat to the traditional garments of the Victorian Era. With long hair and heavy, layered clothing, Flappers' Victorian mothers bore quite the contrast to the slim mini-dresses of the 1920’s youth 7. The Victorians, while conservative in the amount of skin they showed, maintained their own opinions on sexiness and appropriateness of dress. Corsets created hourglass bodies and shoulders peered over the large, generally floor-length, gowns of adult women. Proper Length for Victorian Dress 16 The Village trends, however, changed many feminists’ ideas on acceptable dress and influenced the wardrobe of emerging Flappers. Flappers’ bare knees below their shapeless dresses were more than an initial shock to their mothers. As The New Republic journalist Bruce Bliven wrote, in 1925 “the corset is as dead as the dodo’s grandfather…the petticoat is even more defunct…[and] the brassiere has been abandoned, since 1924” 17. The older generation claimed this as a loss in femininity. Rather than a decline, however, Flappers altered the definition of femininity. If Flappers ever wore bras or corsets, they were ones designed to flatten the woman’s breasts and stomach 13. “The emergence of the boyish figure as the ideal of feminine beauty may seem to belong to the history of fashion, but contemporaries regarded this figure as the symbol of the new morality, a sign of the transition from a sexually and socially heterogeneous society to one that was unisex, uniform and classless” 18. The great cultural and social split between men and women was transformed under the Flappers as she sought equality with men, including in the workforce and in the ability to attend public amusements. Her androgynous figure was just one sign of the homogeneity occurring between men and women in the 1920s. Unlike her mother and grandmother, the New Woman fully painted her face and topped it off with bright red lipstick. The Flappers wanted to make their own decisions and felt that one of the greatest ways to do so was in their physical appearance. In general, Flapper fashion consisted of “dropped waist dresses, shorter skirts, cloche hats, long beaded necklaces, high heels, raccoon coats, and transparent hosiery” 13 . Aside from the raccoon coats worn for evening dates, the Flapper’s attire was light, allowing her well-groomed skin to be shown. The wardrobe weighed approximately a mere two pounds and even less when the flapper decided to roll of her transparent hosiery 17. Sometimes, however, she simply rolled down her stocking to powder her knees. Victorian women, without a beat, were shocked by their daughters' lack of embarrassment. "A Flapper Powders Her Knees" 19 Flappers, however, were spotted in the crowd, above all, because of their characteristic bobbed haircut. The cut added to their boyish figures and was extremely popular on college campuses in the 1920s. The bob was not a factor of race or institutional differences; it was an appealing look to both white students and African American students 13. For the time being, the bob and the entire Flapper wardrobe, united blacks and whites under a common hip-culture. Although, the majority of 1920s American women were not Flappers, the symbolic attire was able to spread to those who desired it, making it a defining feature of 1920s collegiate culture for both black and white adolescents 13. When women saw their favorite feminist actresses and artists in Flapper attire, they could easily imitate them, causing the Flapper to become the symbol of the 1920s flaming youth, not only in America but also abroad. This younger generation showed their ability to alter the national identity to one focused around--both in criticism of and in admiration for--the rebellious and flamboyant youth who were not afraid to shake the social norms. Prominent women emerged in the 1920s from the literary and poetry realm, and of course from the new Hollywood scene that was already uniting Americans at inexpensive theaters. Poet Edna St. Vincent Millay was appealing to America’s young women because of her Greenwich Village-born liberal views of sexuality and her unrestricted personality, personified in her lack of brassiere and her bobbed hair 3. Journalist Louise Bryant also cut her hair and painted her face, and was described as “‘the picture of flaming youth’” 3. These women’s liberal sentiments spread throughout the female culture; the nation’s females were liberalizing. Edna St. Vincent Millay 20 While Flappers were often mistrusted, some saw beneath their activism a certain coy playfulness. The Hollywood film industry “adopted the strategy of poking fun at the foibles of the younger set while at the same time exploiting them…by this means, the younger set was presented as laughable rather than threatening” 21. Actresses such as Clara Bow and Colleen Moore showed Americans, as wells as Western Europeans and Russians, both the wildness and the subtle innocence of the Flapper. Colleen Moore played flappers, including Pat in Flaming Youth, who were both daring yet innocent and playful underneath their wild antics. Clara Bow, while also portraying a Flapper of innocence and sexuality, showed “the flapper’s signature naughty behaviors, such as drinking, smoking and wearing revealing clothing, with an unusually unadulterated degrees of sensual pleasure…” 21. Clara Bow 22, therefore, showed a Flapper, including Pepper Whipple in Love Among the Millionaires who publicly sings while intoxicated, who lacked hesitation in her “wild” actions in contrast to the cautiousness of Moore’s characters. Together Moore and Bow portrayed youthful innocence and sexiness, which allowed the older generation to cope with the somewhat radical female protagonists of the youth generation 21 . Indeed, a sense of innocence existed behind the Flappers’ meticulously painted faces, but if she were spotted at a speakeasy or nightclub, her innocence would be difficult to perceive. These unlawful “hot spots” introduced the youth to the new sensation of jazz music, combined with illegal liquor and sensual dancing. Flappers were known at home and abroad for their taste in upbeat dance styles that positioned them closer to their male companions. Many members of the older generation, including those in the Soviet Union felt that the physical contact and peculiar movements involving in the Flapper’s dances “suggested a loss of control and ‘the abandonment of civilized restraint’” 23. The new youth cultural, however, was simply exploring freedom and developing equality. The Charleston 24 Dancing also strengthened the bond that was beginning between white and black adolescents. After all, “the dace styles, music, and slang identified with white college students in the 1910s and 1920s owed much to African American invention” 12. Jazz music became yet another symbol of the Flapper as she danced the Tango, the Black Bottom, and predominately the Charleston 10. Although jazz was often considered an evil entity, the older generation’s actual issue with the music “seemed to be that jazz dances inspired young women to leave their corsets at home- and loosen up!” 10. As females became more closely connected with young men, she began to make her presence at other previously predominately male gatherings such as baseball games and crew races at men’s colleges 12. Never before had young ladies spent time in such close (physical) contact with young men. Not only was the dancing and frolicking an enjoyment for the youth, but they were also yet another factor which influenced young women’s new sense of sexuality both in America and abroad. Is She Proper? The 1920s Modern Sexuality Under the influence of the self-expressive Flappers and their rowdy beaus “the line between acceptable and inappropriate behavior blurred as…frankness about sex became fashionable” 7. As Flappers became closer with men, women’s thoughts on sexuality and relationships with men changed drastically. Although not all women agreed with the change in opinion, the frankness of the youth spread to other nations and allowed even older women to speak a bit more openly about sex. Reportedly, “the sexualized body of the 1920s student grew out of what historians have termed the first modern sexual revolution (in contrast to the second in the 1960s and 1970s), which developed in working-class neighborhoods and radical circles in the early 1900s before it spread to middle-class youth and college campuses” 13. What began with a few flappers necking and petting behind their mothers’ backs, evolved into an entire revolution for sexuality equality. Unlike the vast majority of Victorian women, many Flappers saw no harm in kissing boys whom they did not intend to marry. Without any embarrassment, one flapper exclaimed kissing as “terribly exciting. We get such a thrill. I think it is natural to want nice men to kiss you, so why not do what is natural?” 25. In the Victorian Era, however, such acts were considered unnatural and completely unacceptable. In fact, amongst all her differences with her mother, it was mostly likely the “sexual freedom of the young people that set the post war generation apart” 14. The “wild dancing” of the Jazz Age youth brought hormonal adolescents practically as close as physically possible. The dances, thus, brought about “postrevolutionary concepts of ‘sexual liberation’ [and] ‘free love’” in both America and abroad 23. The sexual freedom expressed in the works of Sigmund Freud also seemingly gave young men and women the right to openly express their healthy heterosexuality 4. While the frankness surrounding sex made many individuals uncomfortable it could indeed not be ignored within the modernizing youth culture. The 1920s youth, comfortable with their sexuality, also redefined the dating system that began as a mere high school extracurricular activity in the 1890s 14. Beginning with the mentioned privacy of automobiles, America’s view of dating shifting from a quaint supervised meeting, into a system in which the two enjoyed themselves without a chaperone at a social or public amusement event. “Physical intimacy became an expected element of dating” causing the virginal innocence of courtship to decline 14. The Flappers who married found the partnership virtually impossible and unpleasant if it lacked physically intimacy. The nation was overwhelmed by the fact that flapper college students “flirted, kissed, danced, and petted with men. Expected to give and receive sexual pleasure, they used their bodies to explore this new landscape” 12 . Consequently, this physical intimacy led to a new obsession that seemingly never faded: the obsession with being physically beautiful and slim. Especially as women joined sports teams and attended sporting events, they began to see unwanted weight as a personal failing 14. Women strove for what could only be called the “It” factor. “It” could described as a woman with an appealing personality or with sex appeal. Clara Bow was the epitome of the characteristic in the 1927 movie It, and many women could not help but desire her pleasing traits 14 . Hence, the desire for the ideal body began, and, today, still continues. And She Travels Too The Flapper's Influence Abroad The Hollywood movies, filled with flirtatious slim flappers, spread to Eastern Europe and consequently to Russia. As individuals abroad bore witness to the happy-go-lucky youth of America, many members of the younger generation abroad also joined in the festivities. For the older generation, however, “the mass media dramatized common prejudices and inflated the fears aroused by the discovery of the new feminine sexuality” 26. In Britain, Flappers made an impact with their desire for careers and, consequently, their influence on the supposed decline of the family unit. These modern, independent, and of course attractive, girls were reportedly going “out in the world to earn a living, thereby driving men to emigrate” 26. Older Brits, like the older generation of America, mostly worried about the change in social balance strong women would cause. In Paris, dancing played a major role in many middle-class women’s social lives 14. One magazine described “…how the War had upset the balance of the sexes in Europe and the girls over there were wearing the new styles as part of the competition for husbands” 17. Not only were youthful women in Europe becoming resembling American flappers in their competition for jobs, but they also competed against one another, with their strong reproductive instincts and feminine sexuality to obtain men 26. The Flapper on Life Magazine 27 As Western Europe’s youth began dressing in Flapper attire and showing Flapper rebellion, the Hollywood films that influenced these young women were spreading to the Soviet Union. Simultaneously, fashion magazines from Western Europe showed Russian women the desirable fashion that they too could wear. Soon the youth of the bourgeoisie working class, under the New Economic Policy (the Soviet's new economic plan as of 1921), were completely in tune with what their European and American counterparts were both wearing and dancing 28. Russian Flappers defied the Communist Bolsheviks and their pressure for cultural unity, and instead preferred to indulge in entertainment and “adopted the flapper fashions of Paris and New York and danced to the seductive rhythms of American jazz” 28. Soviet youth, like that of America, also loved to dance. After its début in Paris, the popular dance of the Charleston was introduced to Moscow in 1926 and the youth gathered together to dance alongside traveling American jazz bands. Dance and jazz band acts were soon advertised as “American” and were the symbol of modernity and sophistication 23. American actresses such as Clara Bow also influenced young Soviet women to paint their faces, bob their hair, and adorn themselves in short dresses and high heels in order to imitate the Silver Screen “heroes” 29. The angered Bolsheviks felt their balanced society and hope for “creating cultural hegemony” was threatened. However, cultural hegemony was indeed in the making, though not between the youth and adult Communists of the Soviet Union. Instead, a new youth culture was forming throughout many of the advanced countries of the 1920s. What began as a spread of fashion-keen feminists in the United States spread throughout races and ethnicities to form an entirely new youth culture. Flappers taught the youth to address their desires and concerns for equality and pleasure. They additionally, though often scorned because of it, advocated women’s ability to talk more openly about sexuality and relations with males, and even created a stronger bond between men and women throughout the nations. What the Bolsheviks saw as “hooliganism” was actually the rebellious youth forming a self-identity 28. A Change of Mind The Older Generation Catches On Flapperdom still did not maintain the majority of these nations’ youth, but it was certainly forming a new youth identity. Soon, however, individuals from the flappers’ mothers’ generation began joining in the new beliefs and style. By 1925, the symbolic flapper look was “being worn by all of [Flapper] Jane’s sisters and her cousins and her aunts. They [were] being worn by ladies who [were] three times Jane’s age” 17. Although mothers and aunts probably did not wear so short of dresses or as much makeup as youthful Flappers, the youth cultural was evidently influencing the older generation. Indeed, the new modern women could not be ignored. The Flapper's Mother 30 More importantly than a change in attire, some of the older generation in the twenties desired the youth’s free character. “Even some older women participated in describing a new kind of femininity, one that had eliminated the problems experienced by the older generation of women” 4. These older women grew up with their behavior and freedoms repressed and oftentimes remained unaware of issues involved with sexual relationships. The New Women, on the other hand, appeared to give the entire female cultural hope for a more knowledgeable future. As the older generation began accepting some of the youth’s flaming antics and personalities, the large generation gap that had lasted most of the 1920s began fading, reuniting mother and daughter and father and son. The New Women were able to openly discuss syphilis, kissing, and other phenomena of the new sexual culture, allowing both men and women to have safer, healthier courtships 4. She Left Her Mark Conclusion The 1920s were filled with shock, excitement, social and relationship changes, but by 1929 the Flapper was fading out of existence. When the stock market crashed and the prices of goods shot up, middle and working class women found it much more difficult to afford the Flapper fashion. It became more convenient to be partially dependent on a partner, especially one who showed romance and compassion 14. During the depression, the youth were forced to focus more on surviving and retaining somewhat of a normal life, rather than on advocating modernized freedoms for women. Flappers faded out of the Soviet Union shortly after because by 1932, the Bolsheviks had tolerated enough from the excessive youth and prevented American jazz bands from performing throughout the country 29. The Flapper diminished by the end of the twenties, but not without leaving her mark on society. The Flapper was not just a spunky rebellious young woman who strove to defy her mother’s traditions and caused uproar in society (although she certainly did so along the way). Rather, the Flapper was, and still is, the key symbol of the loud, modern youth of the 1920s. Her frankness about sexuality created both a new emotional and sexual culture for women, and a new foundation for male and female courtship. She shook the social norms and rocked the traditional female roles. She showed women across the globe that being submissive could only harm the potentially remarkable female. More than anything else, however, the Flapper created a new youth identity, not only in the United States but also in Europe and Russia. The older generation was all well familiar with the “Flaming Youth” and its dare to be free. She was “Making Noise.” She was The Flapper. Footnotes 1 "Flapping Not Repented Of." The New York Times. The Twenties: Fords, Flappers & Fanatics. Ed. George E. Mowry. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1963. 173-175. 2 The Sophisticated Flapper, http://www.geocities.com/flapper_culture/jane.html (accessed February 23, 2007). 3 Saville, Deborah. "Freud, Flappers and Bohemians: The Influence of Modern Psychological Thought and Social Ideology on Dress, 19101923." Dress (USA) 30 (2003): 63-79. Academic Search Premier. 23 February 2007. http://search.ebscohost.com. 4 Laura Davidow Hirshbein, “The Flapper and The Fogy: Representations of Gender and Age in The 1920s.” Journal of Family History 26 (2001): 112-128. http://jfh.sagepub.com/cgi/reprint/26/1/112 (accessed February 23, 2007). 5 Tom Dalzell, Flappers 2 Rappers: American Youth Slang (Springfield: Merriam-Webster, Incorporated, 1996), 8-23. 6 George E. Mowry, ed., The Twenties: Fords, Flappers & Fanatics. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1963. 173. 7 Norton, Mary Beth, David M. Katzman, David W. Blight, Howard P. Chudacoff, Fredrik Logevall, Beth Bailey, Thomas G. Paterson, William M. Tuttle, Jr. A People and A Nation: A History of The United States. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2005. 651-677. 8 The automobile was a principal symbol of the new era, http://ehistory.osu.edu/osu/mmh/clash/Introduction/Intro.htm (accessed April 20, 2007). 9 Standing Out in the Crowd: Advertising/ flapper, "Images of the Jazz Age." http://classes.berklee.edu/llanday/fall01/jazzage/crowdweb (accessed February 23, 2007). 10 Pick, Margaret Moos.“Speakeasies, Flappers & Red Hot Jazz: Music of the Prohibition.” http://www.riverwalkjazz.org/site/PageServer?pagename=jazznotes_sp eakeasies (accessed February 23, 2007). 11 "Women Smokers." The New York Times. The Twenties: Fords, Flappers & Fanatics. Ed. George E. Mowry. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1963. 178-179. 12 Page, Ellen Welles. “A Flapper’s Appeal to Parents.” Outlook Magazine (1922), http://www.geocities.com/flapper_culture/appeal.html (accessed February 23 2007). 13 Lowe, Margaret A. Looking Good: College Women and Body Image, 1875-1930. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 2003. 103133. 14 Spurlock, John C. and Cynthia A. Magistro. New and Improved: The Transformation of American Women's Emotional Culture. New York: New York University Press, 1998. 17-52. 15 Fashions for Autumn of 1928, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flapper (accessed February 23, 2007). 16 The Proper Length for Little Girls' Skirts at Various Ages. Harper's Bazar, 1868. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victorian_fashion (accessed April 20, 2007). 17 Bliven, Bruce. "Flapper Jane." The New Republic (1925),http://www.geocities.com/flapper_culture/jane.html (accessed February 23, 2007). 18 Melman, Billie. Women and the Popular Imagination in the Twenties: Flappers and Nymphs. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1988. 1-12. 19 A Flapper Powders Her Knees, http://www.geocities.com/flapper_culture/jane.html (accessed February 23, 2007). 20 Edna St. Vincent Millay, http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/USAvanzetti.htm (accessed April 22, 2007). 21 Ross, Sara. "'Good little bad girls': Controversy and the flapper comendienne." Film History [Australia] 2001 13(4): 409-423. Academic Search Premier. 23 February 2007. http://search.ebscohost.com. 22 "Clara Bow 'Rarin' to Go.'" Love Among the Millionaires (1930), http://youtube.com/watch?v=Z_z5o-ONqg8 (accessed April 19, 2007). 23 Gorsuch, Anne E. Flappers and Foxtrotters: Soviet Youth in the "Roaring Twenties". Pittsburg: University of Pittsburg, 1994. 7-13. 24 The Charleston, http://www.abc.net.au/rn/bigidea/stories/s1404782.htm (accessed April 21, 2007). 25 Wembridge, Eleanor Rowland. "Petting and the Campus." The Twenties: Fords, Flappers & Fanatics. Ed. George E. Mowry. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1963. 175-178. 26 Melman, Billie. Women and the Popular Imagination in the Twenties: Flappers and Nymphs. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1988. 15-37. 27 Life (1922), http://www.compassrose.org/uptown/nirvana.html (accessed April 20, 2007). 28 Gorsuch, Anne E. Flappers and Foxtrotters: Soviet Youth in the "Roaring Twenties". Pittsburg: University of Pittsburg, 1994. 1-7 29 Gorsuch, Anne E. Flappers and Foxtrotters: Soviet Youth in the "Roaring Twenties". Pittsburg: University of Pittsburg, 1994. 13-24 30 A Cartoon About Flappers (1927), http://www.colorado.edu/AmStudies/lewis/2010/flapper.htm (accessed April 22, 2007). Edit - History - Print - Recent Changes - Search Page last modified on April 27, 2007, at 12:01 AM