The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Hormones and Low Dose Oral

advertisement

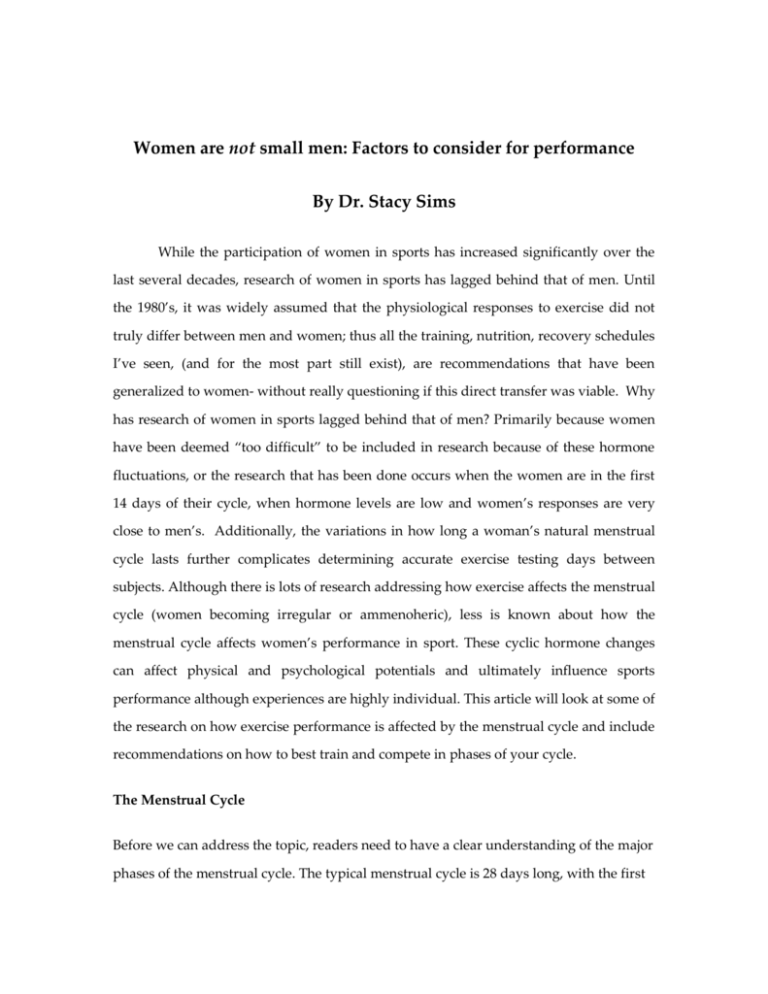

Women are not small men: Factors to consider for performance By Dr. Stacy Sims While the participation of women in sports has increased significantly over the last several decades, research of women in sports has lagged behind that of men. Until the 1980’s, it was widely assumed that the physiological responses to exercise did not truly differ between men and women; thus all the training, nutrition, recovery schedules I’ve seen, (and for the most part still exist), are recommendations that have been generalized to women- without really questioning if this direct transfer was viable. Why has research of women in sports lagged behind that of men? Primarily because women have been deemed “too difficult” to be included in research because of these hormone fluctuations, or the research that has been done occurs when the women are in the first 14 days of their cycle, when hormone levels are low and women’s responses are very close to men’s. Additionally, the variations in how long a woman’s natural menstrual cycle lasts further complicates determining accurate exercise testing days between subjects. Although there is lots of research addressing how exercise affects the menstrual cycle (women becoming irregular or ammenoheric), less is known about how the menstrual cycle affects women’s performance in sport. These cyclic hormone changes can affect physical and psychological potentials and ultimately influence sports performance although experiences are highly individual. This article will look at some of the research on how exercise performance is affected by the menstrual cycle and include recommendations on how to best train and compete in phases of your cycle. The Menstrual Cycle Before we can address the topic, readers need to have a clear understanding of the major phases of the menstrual cycle. The typical menstrual cycle is 28 days long, with the first day of menses considered Day 1. Menstruation is usually completed by Day 5 -7, and the mucosal lining (endometrium) of the uterus once again begins to proliferate in preparation for an egg. The phase from Day 1 to ovulation, which is normally Day 14-15, is called the follicular phase. The luteal phase is from ovulation until the day before menses, normally about Day 2. With a triphasic oral contraceptive pill, the first active hormone pill is taken on Day 1, with low hormone levels lasting from Day 1-5, moderate levels lasting from Day 6 – 10, and the highest hormone levels lasting from Day 11 -21, with a sugar pill or no pill taken for Day 22 – 28, allowing for breakthrough bleeding to mimic a period. Due to the varying hormone concentrations with OCP, there is not a follicular or a luteal phase, just low and high hormone phases (Figure 1). Serum Concentrations (ug) Triphasic OCPs vs Endogenous Hormones ethinyl-E progestin oestrogen progesterone 150 135 120 105 90 75 60 45 30 15 0 1 4 7 10 13 16 19 22 25 28 Time (days) Figure 1. Triphasic OCP vs Natural menstrual cycle hormone concentrations As most women know, symptoms that accompany menstrual cycles vary considerably. Some women do not experience any symptoms; others may suffer slight discomfort to severe pre- or initial-flow discomfort. Changes in exercise performance during the menstrual cycle vary as well. Many women report impaired performance and just as many not. There are a number of women who have won Olympic medals while menstruating. Some women may experience some minor discomfort but merely push themselves forward during participation. Because most variations in performance are due to the high hormone levels, let’s look at how high levels of estrogen and progesterone, both natural and from oral contraceptives have an effect on women and performance. METABOLIC CHANGES-a.k.a FUELING One important factor to note is recent research on oral contraceptives has illustrated a rise in naturally produced estrogen during the sugar pill week. Thus, although almost every article and text out there describes the sugar pill week as being “low hormone” this is not necessarily the case. Van Heusen and Fauser (1999) observed significantly higher concentrations of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and natural estrogen at the end of the pill-free interval, and the higher the amount of estrogen in the OCP, the less natural estrogen was secreted in the pill free week (Creinin et al. 2001, Schlaff et al. 2003). What does this mean, to the casual reader and female athlete? Estrogen decreases the reliance on liver glycogen, increases the use of fat, and decreases amino acid breakdown during exercise. These fuel responses have been attributed to a sex difference between catecholamine responses during exercise (men release a larger amount of catecholamines at a given moderate-high intensity exercise load than women who have similar training status). This glycogen sparing, increased fat use is even greater during the high hormone phase (luteal phase) of the menstrual cycle- when estrogen is at its highest concentrations. How does this translate to everyday practical use? Women have a greater capacity for burning fat and sparing glycogen (both in the liver and the muscle) in the high hormone phase. To maintain the capacity to hit intensities, women should look to stay ontop of carbohydrate intake during exercise; BUT during the low hormone phase, women can afford to ingest less exogenous carbohydrate than her age and fitness matched male counterpart (think: 45-55g per hour as opposed to the 65-80g per hour). “So does this mean I need to eat more fat?” Actually, not necessarily….Researchers have looked at the recovery phase in men and women. Although women metabolize and use more fatty acids during prolonged exercise (and we have greater fat stores than men), women have a greater ability to maintain energy substrate stores during exercise and during recovery. Three hours post-exercise, men still have higher rates of blood glucose fluctuations and lower glycogen stores, whereas women are relatively close to the preexercise state (side note- this also contributes to the harder-to-get-lean factor many women face- less of a window of elevated metabolic state and fatty acid use at rest). What about protein use during exercise? Women also oxidize less protein and leucine than men even though there is no sex difference in the muscle enzyme that controls the intramuscular use of branch-chained amino acids. But, during the high hormone phase of the menstrual cycle, progesterone (or a lower estrogen to progesterone ratio) increases the use of protein during exercise. This phase difference is important to note for recovery- amino acids are key to immune function as well as muscle adaptations to stress. “Okay, ok, so there ARE sex differences in how my body fuels itself for exercise; but how do I take all this info and apply it?” Key points to take onboard: Women have greater fat stores and access fat to a greater degree during exercise; sparing liver glycogen. Women don’t oxidize as many branch-chained amino acids during exercise as men, but in the high hormone phase of the menstrual cycle, there is a greater reliance on protein during exercise and at rest, thus recovery protein intake is critical for muscle synthesis and recovery The post-exercise recovery phase: three hours post-exercise, a woman’s metabolism is pretty close to pre-exercise/baseline levels; so the 2-hour recovery window after the first of a 2xday exercise session needs to be carefully planned, in order to restore the muscles’ fuel stores. The quick return to baseline metabolism also contributes to the reduced ability to “lean up” in women- again, need to take advantage of the 2-hour window to promote body composition change and glycogen/fat store recovery. What about HYDRATION? Plasma volume is the watery component of blood that reduces the thickness of the blood and allows blood to flow quickly to working tissues. When we begin to sweat, it is the plasma volume that is lost first, as it is this fluid that helps make up the sweat. We sweat to remove heat. As women, we have an elevation of our resting core temperature in the luteal phase of the natural menstrual cycle, and in the last 15 days of OCP use, due to elevated progesterone concentrations. The increased progesterone stimulates the phrenic nerve, increasing respiration and it also acts to increase sweat production later than in the low hormone times of the menstrual cycle. So, with elevated progesterone, there is a natural resetting of the baseline body temperature by as much as 0.3 -0.5 °C. Coupled with an increased time to sweating during the luteal (high hormone) phase, it can be seen that athletic performance is compromised in the luteal phase due to higher body temperature and less ability to get rid of the heat. What’s more, is the high estrogen and progesterone act on the kidney’s hormones to reduce plasma volume, a drop of up to 8% from ovulation to the mid-luteal phase, and this fluid goes between the cells; causing the bloating often associated with PMS. In general, during the luteal phase and the high hormone phase of the menstrual cycle, women are less able to cope with the heat and have a reduced ability to sweat to remove the heat from deep inside the body. How do I compensate for this shift in temperature and body water? Pre-hydrate! Using a sodium based hyper-hydration drink before high intensity or race situations will help slow down the rate of dehydration (water alone won’t work, you need a bit of sodium to help pull fluid into the vascular spaces of the body) If you’re not racing or training high intensity, be sure to stay on top of your hourly drinking- I recommend fluid intake based on body weight: 0.15- .018 ounces per pound of body weight per hour (lower intake for slower and cooler conditions). Pre and post exercise cooling: Pre-cooling with the ingestion of cold drinks (if possible, use this technique on the bike as well) Post-Exercise: cool water or cool towel against the skin (not icy!) to facilitate blood flow back to the muscles to reduce heat and facilitate recovery INJURY?? Something else to think about is musculoskeletal and joint injuries. There is a higher incidence of these types of injuries right before your period comes. But, we aren’t sure exactly why, as there is little definitive research indicating the exact causes. One theory is a relationship of increased relaxin levels and increased flexibility and elasticity of connective tissue in and around the joints. Relaxin is a hormone that is thought to be responsible for softening and relaxation of the ligaments in joints. Although still poorly understood in humans, relaxin levels highly correlate with relaxing of the pubic bones allowing for birth in females of several mammal species. Relaxin is thought to create joint laxity, which allows the pelvis to accommodate the enlarging uterus. This may also weaken the ability of for the lumbar spine to withstand impact and twisting forces. Thus low back and knee injuries from stepping down wrong and twisting are common during PMS and menstruation. What about the POST-Menopausal Athlete? As more and more women are staying highly active and competitive into their late 40s and beyond, there are specifics for the post menopausal athlete. A few key points to remember when the hormone flux is taken away (aka menopause)1) Blood vessels are less compliant (meaning blood pressure changes are slower) 2) There is less core temperature flux tolerance (meaning you can't handle hot very well) 3) You sweat later in activity and vasodilate longer (i.e. your body tries to get rid of heat by sending more blood to the skin instead of relying on sweating to cool you off for a longer period of time) 4) There is greater sensitivity to carbohydrate (more blood sugar swings and less need for carbohydrate overall) 5) The body uses protein less effectively (meaning that the type and quality of protein you eat and when you eat it becomes very important for building lean mass and holding onto it) 6) Less power production (thus train for power, not for endurance!- on the bike and in the gym!) Potential solutions! For 1 and 2: Cooling post exercise is a great way to facilitate blood flow for recovery. Using cool towels or cool water immersion to get a bit of skin constriction- pushing the blood back into central circulation. During exercise, consume cool foods and fluid (if possible). For 3: Focus on hydration- food in the pocket, hydration in the bottle. Using the pre-hydration technique before racing will help. 4: Aim for 40-50g carbohydrate per hour; not 60-90g. Upping your calorie needs with mixed macronutrient foods 5: Take 15g whey isolate or 9g branch chained amino acids 30 min before training; and definitely 25 g mixed whey isolate and casein within 30 min post exercise. (NOT soy as there is not enough leucine for post menopausal women to promote muscle synthesis). For recovery: another 20-25g mixed whey+casein 2 hours post training with another ~10- 15 grams protein before bed!!! 6: Focus on power training- the speed and strength of muscle contractions tends to diminish with age; thus power and speed becomes an essential aspect of the postmenopausal woman’s training arsenal. In a nutshell Research on women and athletic performance is lagging, but there is information available to maximize training for performance. Knowing that the high levels of estrogen and progesterone associated with the luteal phase, and OCP use affect metabolism, blood flow, thermoregulation, and overall performance can allow women to alter their racing schedule to maximize performance. Moreover, although OCP use is lessening, there are still many women athletes who use the pill to alter their cycles. I have several women athletes who regularly compete in the hot Hawaii and Spanish environments. I have found that by altering their cycles to compete 2 – 3 days post-bleed has produced excellent performances. This can be attributed to controlled low levels of estrogen and progesterone leading to increased aerobic and anaerobic capacity, lower core temperature, greater plasma volume, and a greater ability to sweat as compared to the later stages of their cycles. It is impossible to alter the training and racing cycles to maximize the benefits of low hormones. However, you can schedule your training to be able to maximize your session in accordance to the phase of your menstrual cycle. For example, schedule your high intensity sessions during the low hormone phases, while scheduling longer recovery and steady state (low to moderate intensity) weeks during the high hormone phases of your cycle. You can begin by keeping a training log and monitoring your cycle versus your performance. From this, you will be able to establish the strongest and best training days and when to back off. This will facilitate modifying a training schedule by planning for strenuous sessions, peak training and when rest is needed.